Melanocortins and appetite: Difference between revisions

imported>Gareth Leng |

imported>Gareth Leng |

||

| Line 57: | Line 57: | ||

Although Peptide YY is an appetite suppressor, it appears to mediate its effects through a distinct pathway that does not involve the melanocortin system as both POMC and MC4R KO mice continued to show a decrease in food intake following its administration, indicating that another system may be involved. | Although Peptide YY is an appetite suppressor, it appears to mediate its effects through a distinct pathway that does not involve the melanocortin system as both POMC and MC4R KO mice continued to show a decrease in food intake following its administration, indicating that another system may be involved. | ||

Revision as of 18:21, 4 February 2011

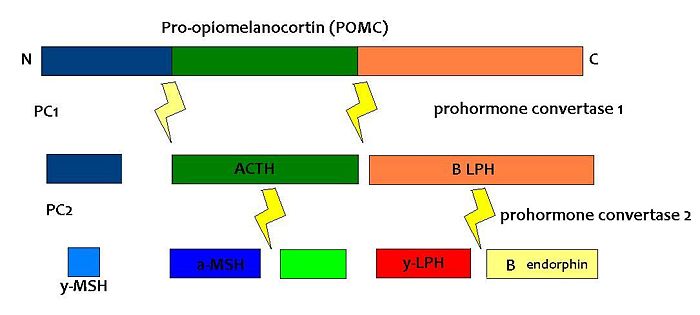

Melanocortins are peptides derived from pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC), determined by tissue-specific post-translational cleavage. The regulation of appetite involves a complex interplay between circulating hormones, neurotransmitters, neuropeptides and nutrients, and the melanocortin system is an important component of this.

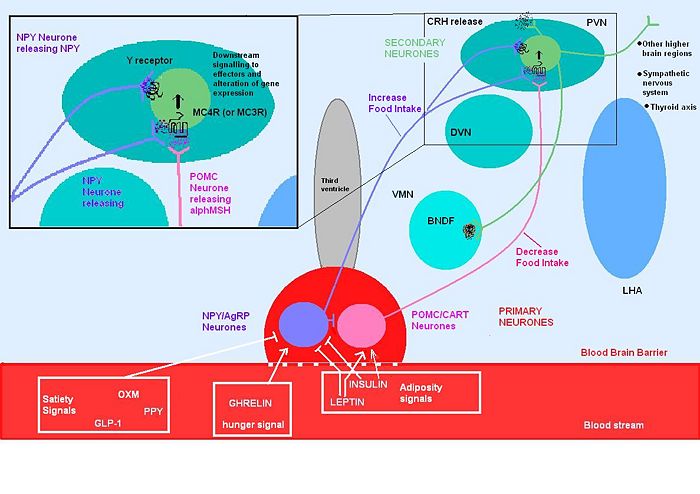

POMC is expressed in many tissues including the pituitary gland and the brain, and its products are involved in many different physiological processes. In the brain, POMC is expressed in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus and the nucleus tractus solitarii (NTS) of the caudal brainstem, and products of POMC are particularly important in appetite regulation. Obesity can arise as a result of a POMC deficiency. POMC expression in the arcuate nucleus is regulated by leptin, a hormone secreted by adipose tissue. Both the opioid peptide B endorphin and the melanocortin alpha-melanocyte stimulating hormone (α-MSH) are cleaved from POMC; α-MSH is a very potent inhibitor of feeding behaviour, but β endorphin increases feeding behaviour (especially of highly palatable foods). It is therefore important to explore how the prohormone may be processed in different tissues and what dictates this. In the same sense, how are the cleavage enzymes regulated to produce various concentrations of the different peptide hormones? In the brain, the actions of α-MSH are mediated via specific melanocortin receptors - particulary MC3 and MC4 receptors. These receptors are unusual in that they have both endogenous agonists and antagonists.

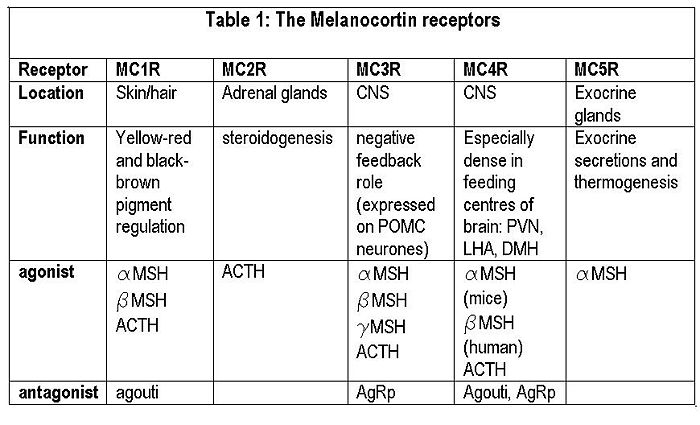

AgRP and α-MSH are involved in appetite regulation mainly via their actions on MC4 receptors. Some MC4 receptors have been found on adipocytes, suggesting that circulating melanocortins may also be involved in regulating energy homeostasis.

Agouti is an antagonist at MC1 and MC4 receptors, while AgRP iis an inverse agonist at MC3 and MC4 receptors. Mutant mice with ectopic expression of these peptides are hyperphagic with an increase in adipose mass, lean mass, and hyperinsulinemia.

In addition to suppressing appetite, α-MSH increases both metabolism and body temperature, which is referred to as a coordinated catabolic pattern. [1]

PC1 and PC2 are expressed in cells other than POMC cells and have important physiological functions other than POMC cleavage. For example, PC1 is essential for the biosynthesis of insulin and PC2 for the biosynthesis of glucagon. However, transgenic mice deficient in PC2 (PC2 'knockout' mice) exhibit no α-MSH expression at all, and Prader Willi patients have reduced hypothalamic PC2 expression. [2] The PC2 knockout mice are so defective in other ways that it is hard to tell whether the lack of alpha MSH has an effect.[3] Prader Willi sufferers do exhibit an obese phenotype but again this syndrome comes as a result of a mutation of several genes so it cannot be inferred that PC2 mutation is solely responsible for the obese and hyperphagic phenotype.

Leptin-deficient mice show an upregulation of POMC and PC2 expression. [4]

POMC was first noted for its importance in appetite and obesity in rodent studies. POMC-null mice were seen to exhibit hyperphagia and obesity without insulin resistance. Their adrenal gland was also atrophic and glucocorticoid levels were undetectable as a result of a lack of ACTH stimulating adrenal cell secretion and proliferation. The suggestion that POMC has a role in energy balance is supported by studies on rare individuals with POMC mutations. In humans, a lack of POMC is generally fatal unless glucocorticoids are administered from birth as cortisol is essential for humans, but a few rare individuals with the mutation have shown very similar phenotype to the POMC knockout mouse.

While these studies show that POMC-derived hormones may have a role in energy balance they don’t tell us which peptides are responsible for the effects and furthermore the lack of adrenal hormones as a secondary result of POMC lack may overshadow the primary POMC effects. Therefore we are required to look at the peptides in more detail.

Melanocortin receptors

The central melanocortin system involves several agonists such as α, β, γ MSH and two inverse agonists, agouti and AgRP. These act on five subtypes of MC receptors (MCR1-5). The system encompasses a number of CNS circuits including

- α-MSH -containing neurons of the arcuate nucleus.

- POMC neurons in the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS)

- AgRP- containing neurones of the arcuate nucleus. AgRP is an inverse agonist at MC4 receptors, thus opposes the actions of α-MSH. AgRP is co-expressed by the orexogenic neurons that make neuropeptide Y (NPY). MC4 agonists reduce food intake and increase energy expenditure, thus reducing body weight, wheras MC4 antagonists enhance food intake (hyperphagia) and decrease energy expenditure, and thus increase body weight.

Peripheral and central melanocortin systems also mediate several other physiological processes within the body including cardiovascular control, inflammation, natriuresis and sexual function.

Although the melanocortin system is central to the regulatory mechanisms controlling appetite and satiety, the precise mechanism is not fully understood. Complexity arises from both the direct and indirect effects of a number of compounds including leptin, insulin, glucose, ghrelin, NPY, serotonin, peptide YY and endorphin.

Genetic mutations of the system, can result in individuals which are hyperphagic and consequentially obese. A number of mutations of this system have been identified in mice, all of which show a dysregulation in energy homeostasis. Many of the mutations discovered involve excess production of POMC antagonists, so that melanocortin agonists can’t bind to melanocortin receptors to suppress appetite.

Leptin is produced primarily in white adipose tissue but also to some extent in brown adipose tissue, stomach, placenta.

Leptin secreted from adipose tissue and insulin secreted from the pancreas also regulate food intake. Excess adipose tissue (in obese individuals) results in an increase in leptin production, which normally induces a feeling of satiety, but excess production of NPY (as occurs in some mutations of the melancortin system), can suppress its effects. Similarly insulin levels show a marked increase in obese individuals, with hyperinsuliemia being one of the first metabolic disturbances identified in those obese subjects with mutations of the melanocortin system.

Insulin After a meal, there is a dramatic increase in insulin levels, some of which crosses the blood-brain barrier in a concentration that is representative of circulating insulin levels. Central administration of insulin acts on both NPY and POMC systems, and increases POMC mRNA synthesis as well as inhibiting food intake in fasting rats. Rats with untreated diabetes have a diminished amount of POMC mRNA, which is indicative of its involvement in stimulating its synthesis.

Ghrelin Ghrelin stimulates arcuate nucleus production of NPY and AgRP, while inhibiting the suppressive effects that leptin induces on appetite. Ghrelin administration in rats produces hyperphagia and increased body weight.Central administration of ghrelin results in excessive eating, accompanied by increased arcuate NPY and AgRP expression.

An example of the complexity that arises in fully understanding the precise mechanism governing this system arises from mice AgRP KO models. Interestingly, while the involvement of AgRP in the melanocortin system is undisputed, one would expect such KO to present with altered phenotypes and eating patterns, yet these AgRP were just like their wild type counterparts.

NPY is one of the most abundant and potent orexigenic peptides of the hypothalamus. Administration of NPY produces a prolonged and substantial increase in food consumption and a decrease in thermogenesis, resulting in an increase in body weight. During times of fasting, low levels of insulin and leptin result in the up-regulation of NPY synthesis.

AgRP AgRP inhibits the effects of α-MSH on inducing its anorexigeneic effect. AGRP is expressed only in the arcuate nucleus of the hypothalamus. All neurons expressing AgRP also produce NPY. Leptin inhibits the expression of AgRP, while periods of starvation result in an increase in its expession. Unlike NPY which induces strong, short lived effects on stimulating appetite, AgRP administration can induce hyperphagia for up to one week.

Thus, when energy stores are low, there is reduced leptin released from adipose tissue, which in turn allows in an increase in the production of orexigenic peptides including NPY, AgRP and a decrease in alpha-MSH. The opposite is true in times of positive energy imbalance.

Although Peptide YY is an appetite suppressor, it appears to mediate its effects through a distinct pathway that does not involve the melanocortin system as both POMC and MC4R KO mice continued to show a decrease in food intake following its administration, indicating that another system may be involved.

Suggested future studies

Despite the importance of melanocortins for appetite regulation, much of the underlying molecular mechanisms that facilitate the melanocortin signalling pathways remain unidentified.

Melanocortin Receptors G-proteins: A question of cross-talk? POMC expression is up-regulated in α-MSH neurones as result of increased leptin and insulin signalling. This has been proposed to increase α-MSH release which acts predominantly through activation of the G-protein coupled receptors MC3R and MC4R which are Gs linked receptors. Gs stimulate the up-regulation of adenylase cyclase and thus increase cAMP levels, and a multidude of sequential kinase signalling resulting in a complex cascade of second messengers that facilitate its anorexigenic effects and prevent orexigenic pathways.

Recent studies have unveiled the possibility for the involvement of alternative G-proteins or the coupling of G-proteins to create a specific effect. However, there are contradictory studies between the involvement of Gq’s and the activation of PLC and calcium signal which has been seen in some studies but not in others however, the cell lines used were different and furthermore the results are yet to be confirmed in vivo [5] [6]. Another study found that the inhibition of Gi/o specific cells expressing MC4R treated with agonist created a suppression of ERK1/2 phosphorylation indicating a possible role for Gi’s and downstream PKC/calcium activation of ERK 1/2 as opposed to conventional Gs PKA signalling initially described in certain cell types [5]. Clearly, these areas of research is open to clarification in terms of the G-proteins involved in melanocortin signalling and activation of important downstream activity of molecules such as ERK 1/2 and thus enable us to fine tune the understanding of appetite regulation.

α-MSH release Little is understood, at the molecular level, of how and where α-MSH is actually released. There is very little evidence of studies into the process by which it is exocytosed and more research into the storage and release mechanisms of α-MSH is required to understand the αMSH pathway and bring insight into any other possible means of targeting this pathway.

Melanocortin 3 Receptor (MC3R) Although the MC3R is implicated in appetite regulation it does not have such in-depth association with obesity as the MC4R has. However, studies have shown that mutations, heterozygous genotype and knock out experiments can create the pathophysiological state or at least predispose humans and murine species to obesity either in childhood or later in life, especially apparent when coupled to an obesigenic environment [7]. Moreover, there is confusion as to the roles that this receptor has in an anorexic effect since it is also thought that it is part of the auto-regulation of POMC providing negative feedback. Studies of MC3R knockout mice show primarily alterations to in metabolic syndromes whereas MC4R alters feeding behaviour and intake as well as energy expenditure [8].

Agouti-related protein signalling: antagonist or inverse agonist? AgRP is thought to have a competitive antagonistic role on MCR to prevent αMSH signalling however, AgRP can produce autonomous orexigenic effects by reducing the cAMP increase caused by binding of αMSH potentially through Gi signalling suggesting that it has inverse agonist qualities. This is primarily observed in terms of its ability to reduce cAMP levels [9]. Recent studies have reiterated these findings for a AgRP's role as an inverse agonist in-vivo as well as eluding to recent studies in MC4R knock out mice in which AgRP induced hyperphagic state was still observed suggestive of its action through a receptor independent of the melanocortin receptors [10]. The exact composition of MCRs and the complexes that are formed at the membrane is an avenue that requires exploration especially since the picture is complex; MCR could potentially interact with a variety of G-proteins, accessory proteins such as syndecans, mahoganoid and especially MRAPs with MC4R to manipulate various aspects of αMSHs signalling capacity [7].

Lipid rafts The cholesterol composition of the lipid membrane affects cAMP signalling, with higher levels dampening the cAMP response because the lipid rafts segregate the G-protein signalling components accessibility to each other. Accordingly, the lipid micro-domain surrounding the MCR’s within the membrane may alter the result of α-MSH signalling to produce cell-specific effects.[5].

A role for BNDF/Trk signalling The neurotrophic brain-derived neuronal growth factor (BNDF) acts through the tropomysin receptor kinase B (Trk) and is thought to be activated downstream of melanocortin signalling through MC4R. This is proposed to be due to the ability of synthetic mineralocorticoids to promote BDNF expression within the ventromedial nucleus of the hypothalamus (VMH), in addition to the ability of BDNF to blunt feeding in MC4R knockout mice [11]. However, how they interact is not clear and further investigation at the molecular level will shine light on the downstream signalling involved through protein-protein interaction assay techniques such as a GST protein interaction pull down of the 'bait' protein, possibly the section of protein thought most likely to interact with another protein, and wash with cell lysates containing potential 'prey' molecule candidates followed by immunoblotting to assess interactions [12].

Thyroid hormone MC4R is expressed in a variety of neuronal cell types, including the thyrotropin-releasing hormone (TRH) neurones of the PVN, consistent with a role in metabolism and thus energy homeostasis. Inhibitory feedback from thyroxin's (T4) biologically active derivative triodothyronine (T3)is occurring at the MC4R [13].This incidentally alleviates inhibition of food intake and allows the activation of orexigenic pathways. The negative feedback is strongest in the brainstem region where it is thought to regulate meal size and thermogenesis.

Corticotropin Releasing Hormone (CRH) CRH has also been discovered to partake in appetite regulation and studies using double labelling in situ hybridization have found that MC4R is also expressed by CRH neurons inthe PVN. CRH is one of the elements regulated downstream of MC4R activation and aids arexogenic systems, linking the melanocortin pathway to the hypothalamic pituitary axis and thus to an involvement in stress. X. Y Lu et. al (2003)proposes the implications of this connection to stress as resulting in a relation to eating disorders and therefore is of particular interest not merely in treating anorexia nervosa but in terms of potentially opening an avenue of insight into obesityies polar opposite and help aid the research into the requirements for the 'happy medium'[14]. However, more work is required in terms of the exact receptor type that CRH is acting on and also whether the HPA axis requires melanocortin signalling or likewise is the HPA axis required for appropriate melanocortin regulation of feeding?

References

- ↑ Balasko et al. (2010)

- ↑ Millington et al. (2003)

- ↑ Scamuffa et al. (2006)

- ↑ Pritchard et al 2002)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Breit A et al. (2010) Alternative G protein coupling and biased agonism: New insights into melanocortin-4 receptor signalling. Mol Cell Endocrinol doi:10.1016/j.mce.2010.07.007

- ↑ Biaoxin C et al. (2006) Melanocortin-4 receptor-mediated inhibition of apoptosis in immortalized hypothalamic neurons via mitogen-activated protein kinase Peptides 27: 2846-57 doi:10.1016/j.peptides.2006.05.005

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Mountjoy K. (2010) Functions for pro-opiomelanocortin-derived peptides in obesity and diabetes Biochem J 428:305-24 doi:10.1042/BJ20091957 305

- ↑ Butler AA, Cone RD (2003) Knockout studies defining different roles for melanocortin receptors in energy homeostasis Ann NY Acad Sci 994:240-5

- ↑ Nijenhuis WAJ et al. (2001) AgRP(83–132) acts as an inverse agonist on the human melanocortin-4 receptor Mol Endocrinol 15:164–71

- ↑ Tolle V, Low MJ (2008) In Vivo evidence for inverse agonism of agouti-related peptide in the central nervous system of proopiomelanocortin-deficient mice Diabetes57:86-94

- ↑ Oswal A, Yeo GS (2007) The leptin melanocortin pathway and the control of body weight: lessons from human and murine genetics Obesity Rev 8:293-306

- ↑ Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc. (2010) Pierce GST and His Tag Protein Interaction Pull-Down Kitshttp://www.piercenet.com/products/browse.cfm?fldID=42E8E027-6231-4512-8DDE-BB026740966B

- ↑ Decherf S et al. (2010) Thyroid hormone exerts negative feedback on hypothalamic type 4 melanocortin receptor expression PNAS 107:4471–6

- ↑ Xin-Yun L et al. (2003) Interaction between alph-melanocyte-stimulating hormone and corticotropin-releasing hormone in the regulation of feeding and hypothalamo-pituitary-Adrenal Responses J Neurosci 23:7863–72