Circadian rhythms and appetite

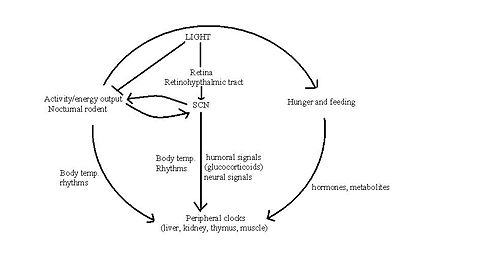

The control of food intake is a flexible system whereby internal and external environmental cues influence the timing of feeding and appetite. The suprachiasmatic nucleus in the hypothalamus is the vital coordinator of these stimuli that ultimately generates fluctuations in neuronal and hormonal activities that are known as circadian rhythms. Circadian rhythms are driven by the daily variations in ambient light, which, by alterating gene expression, elicit a host of physiological responses including fluctuations in the hormones involved in appetite. Various factors such as temperature and social cues influence circadian rhythms; indeed, food intake itself can regulate these rhythms, but the neural mechanisms by which this occurs remains elusive. It has recently been proposed that there is a ‘food entrainable oscillator’ that exists independently of the SCN, and which controls food anticipation activity.

The clock genes

Clock mechanisms in biological cells are formed by the transcription and translation of clock genes, which rely on feedback loops. The clock genes regulate a self-sustaining rhythm in cells that even without light will maintain a roughly 24 hour rhythm. An extreme example is of cave fish which have evolved in complete darkness for millions of years and their clock genes are still present in their DNA.[1]

The rhythmic output of organs can be influenced by metabolic, endocrine and homeostatic events, as well as by the circadian clock. For example, the SCN can change the rhythm of expression of liver genes and enzymes without using clock genes, but through second messenger systems induced by the autonomic nervous system . Other genes can also affect circadian clock genes; for example the ROR-alpha gene is a positive regulator of Bmal1, which regulates lipogenesis and lipid storage. [2]

Genes which encode important proteins of core clock mechanism are Clock (circadian locomotor output cycles kaput); Bmal1 (brain and muscle-Arnt-like 1); the Period genes Per1, Per2 and Per3); and the Cryptochrome genes Cry1 and Cry2. CLOCK (the protein product of Clock) is a transcription factor which dimerises with BMAL1 (the protein product of Bmal1). CLOCK and BMAL1 form a complex which binds to E-box, a DNA sequence in the promoter region of the gene, and to other similar promoter sequences. The binding of the CLOCK:BMAL1 complex to the E-box in the promoter region of ""Per"" and ""Cry"" activates their transcription. In turn, the PER and CRY proteins are able to undergo nuclear transformation and inhibit the CLOCK:BMAL1 complex, resulting in the decreased transcription of their owm genes. CLOCK:BMAL1 and PER-CRY transcription-translation loop is able to detect and self adjust to the changes. CLOCK:BMAL1 and PER-CRY constitute the core of the circadian clock and, because of the delays in transcription and translation, can generate 24 hour rhythms of gene expression.[3] Recent studies on the function and interaction of CLOCK:BMAL1 have shown that it induces transcription in RORɑ and REV-ERBɑ which regulate lipid metabolism and adipogenesis, and Pparɑ, which codes for a nuclear receptor involved in glucose and lipid metabolism.

Studies on mice with impaired Clock function showed increased food intake and eradication of rhythmic expression of Cart and Orexin, CLOCK -/- mice exhibit obesity, altered feeding patterns,hyperphagia and hormonal abnormalities similar to those found in metabolic syndromes, such as hyperlipidemia (abnormally elevated levels of lipoproteins in the blood), hyperglycemia (high concentrations of glucose in blood) and hyperinsulinemia (excess levels of circulating insulin).[3]

The SCN, circadian rhythms and feeding behaviour

A wide variety of organisms, from cyanobacteria to humans, all share common internal clock mechanisms. The circadian clock in mammals sets specific temporal patterns within our bodily systems, including many physiological functions (body temperature, melatonin release, glucocorticoid secretion) and behavioural functions.

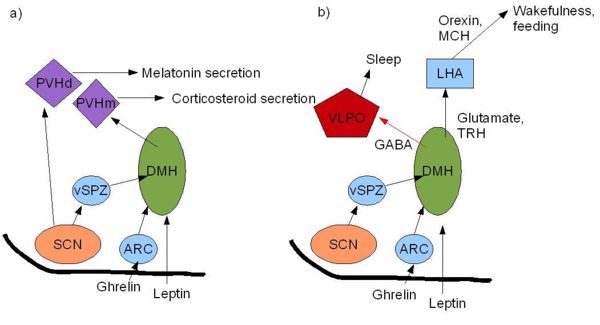

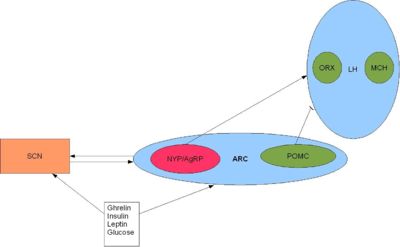

The "master" circadian clock of mammals is in the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus. The SCN receives signals encoding light, which are carried from the retina to the SCN by the retinohypothalamic tract. Vasoactive intestinal polypeptide and other peptides, released from subpopulations of neurones in the SCN, activate and synchronise other SCN neurons, the output of which coordinates behavioural rhythms, including by directing the sleep/wake cycle.

The role of the SCN in feeding patterns has been extensively studied in rodents, as their food intake is less influenced by cognition and social behaviour than in humans. The sleep/wake cycle is driven by fluctuations in two main hormones: corticosterone (cortisol in humans) and melatonin. In rats, corticosterone secretion increases during the night when they are active. This rise is followed by an increase in locomotor activity, in which rats forage for food and subsequently begin to feed. Melatonin is an important hormone that is released from the pineal gland during the night which, amongst its many actions, affects sleep and appetite.

However, these hormones have different physiological roles in different species. For example, melatonin is released during the night in both humans and rodents, and yet latter are nocturnal and therefore most active at night. This indicates that melatonin has opposite effects in rodents and humans in that it appears to drive the awake period in rats and induce the sleep period in humans. Thus whilst the SCN may regulate the sleep-wake cycle, this regulation is species-specific. Nevertheless, it is possible that that the SCN may drive feeding patterns directly as the SCN appears to have reciprocal interactions with the orexigenic regions of the brain namely the lateral hypothalamus.

Alternatively, it is possible that the SCN initiates feeding by conducting circadian rhythmic oscillations in the hormones involved in appetite. Indeed, a number of hormones involved in feeding behaviour and appetite, including leptin and ghrelin, show circadian oscillations. [7]. Leptin exhibits circadian patterns in both gene expression and protein secretion in humans, with a peak during sleep [8]. In rodents, ablation of the SCN eliminates leptin circadian rhythmicity [9] and yet the role of the SCN in conducting this pattern is unclear.

Whilst the role the SCN has in driving feeding behaviour remains elusive, oscillators in other areas of the brain and other organs may also produce rhythmic patterns in feeding. Rodents show food anticipatory behaviour indicating that these peripheral oscillators can be reset by feeding time itself, thus have been named 'food entrainable oscillators'. It has been suggested that the SCN signals to these other oscillators using signalling molecules such as transforming growth factor alpha (TGF-alpha) and prokinecticin 2 that prevent dampening of circadian rhythms in the tissues [3]. [10]

Peripheral Clocks and Food Entrainable Oscillators

- Peripheral clocks

The SCN and peripheral clocks are not affected by meal timings, but restriction of food is the dominant synchroniser for peripheral clocks. When rats are restricted of food, metabolic and hormonal factors used by the SCN to drive peripheral oscillators are uncoupled, to shift to food time. Normally, the SCN and peripheral oscillators work together, but a change in food availability can uncouple them when environmental circumstances demand that feeding patterns are shifted from their normal place in the light-dark cycle.[11].

- The Food Entrained Oscillator

The 'Food Entrained Oscillator' is a mysterious circadian clock, which is independent of the SCN. It ensures that when food is scarce, the body is still ready to digest and extract nutrients from the food that has been found, and is responsible for anticipation of meal-time [1]. Clock genes may contribute to the Food Entrained Oscillator, but are not essential – animals without essential clock genes Bmal1 or per1 or per2 were arrhythmic in constant darkness but still could express food anticipation. [12]

Sleep deprivation, shift-work and appetite

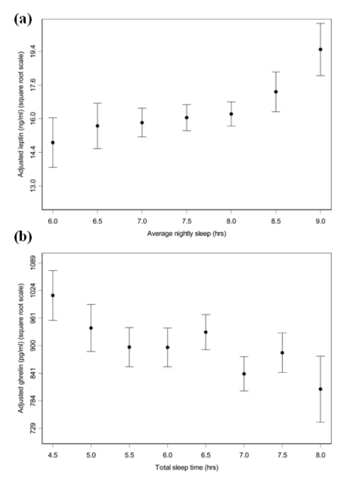

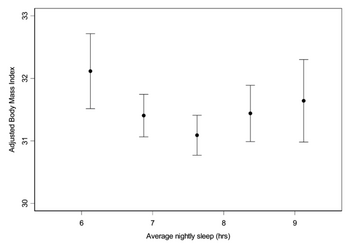

The relationship between sleep duration and serum leptin and ghrelin levels (a) Mean leptin levels vs average nightly sleep duration. As the number of hours sleep increases, the levels of serum leptin also increase. Standard errors for half-hour increments of average nightly sleep. (b) Mean ghrelin levels vs total hours of sleep. As the total number of hours sleep decreases, the mean levels of ghrelin increase. Standard errors for half-hour increments of total sleep time. Adapted from Taheri et al. (2004)

In modern society, shopping, eating, working and drinking are widely available 24 hours a day. Over the last few decades, the number of hours of sleep young adults get has decreased by 1-2 hours. This is correlated with the prevalence of obesity within the U.K which has trebled over the last three decades. Although the rise in this obesity epidemic is multi-factorial, sleep deprivation may be another factor to add to the list needing to be addressed in this ever rising health problem. [13] [14] [15].

Sleep deprivation elevates the circulating levels of the appetite stimulating hormone ghrelin and decreases those of leptin[16][15]. These changes could be the causes of increased food intake in those sleep-deprived adults where a rise in body weight is also observed [16]. It is therefore important to understand the health implications that sleep-deprivation, associated with jetlag and shift working, has on the body in order to develop future therapeutic schemes against such related disorders as obesity.

Conclusion

Over the last decade, significant progress has been made in our understanding of the inter-relationship between circadian biology, sleep and metabolism in the context of obesity. The SCN, which is a vital coordinator of circadian rhythms, may have a role in driving feeding patterns, along with other peripheral oscillators in the brain and organs that produce rhythmic patterns in feeding time.

In the modern world, sleep deprivation is a growing issue of concern and the health implications need to be acknowledged. An adequate number of hours sleep each night is vital for a healthy life. Disruptions of the circadian variations in such appetite-regulating hormones as leptin and ghrelin may contribute to the development of obesity in sleep-deprived patients.

Gaps still remain in our knowledge of the underlying biological rhythms and its association with obesity. So far, previous therapeutic strategies have failed to curb the rising incidence of obesity, but if, through a greater understanding of these complex systems we are able to manipulate and control appetite the benefits will be a healthier population and less strain on the health services.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Mendoza et al.(2009) Brain clocks: From the suprachiasmatic nuclei to a cerebral network. The Neuroscientist 15: 5

- ↑ (Lau et al. 2004)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Froy et al.(2010) Metabolism and circadian rhythms—implications for obesity. Endocr Rev 31:1-24

- ↑ Saper A et al. (2005) The hypothalamic integrator for circadian rhythms Trends Neurosci 28:152-7

- ↑ Yi CX (2006)Ventromedial arcuate nucleus communicates peripheral metabolic information to the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Endocrinology 147:283–94

- ↑ Schwartz MW (2007)Central nervous system control of food intake Nature 404:661-671

- ↑ Yildiz BO (2004) Alteration in the dynamics of circulating ghrelin, adiponectin and leptin in human obesity Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 101:10434-9

- ↑ Kalra SP(2003) Rhythmic, reciprocal ghrelin and leptin signaling: new insight in the development of obesity. Regul Pept 111: 1–11

- ↑ Kalsbeek A (2001) The suprachiasmatic nucleus generates the diurnal changes in plasma leptin levels. Endocrinology 142:2677–2685

- ↑ Gilbert J (2009) Behavioral effects of systemic transforming growth factor-alpha in Syrian hamsters. Behav Brain Res 198:440-448

- ↑ Escobar C et al. (2009) Peripheral oscillators are important for food anticipatory activity (FAA) Eur J Neurosci 30:1665–75

- ↑ Pendergast et al' (2009)

- ↑ Gimble JM et al. (2009) Circadian biology and sleep: missing links in obesity and metabolism? Obesity Rev 10(suppl 2):1-5

- ↑ Rennie KL, Jebb SA (2005) Prevalence of obesity in Great Britain Obesity Rev 6:11-2

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Spiegel et al.(2004) Sleep curtailment in healthy young men is associated with decreased leptin levels, elevated ghrelin levels, and increased hunger and appetite Ann Internal Med 141:846-50

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Taheri et al. (2004) Short sleep duration is associated with reduced leptin, elevated ghrelin, and increased body mass index PLoS Medicine 1:e62