Nuclear chemistry

Nuclear chemistry is a subfield of chemistry dealing with radioactivity, nuclear processes and nuclear properties. It includes:

- the chemistry of radioactive elements such as the actinides, radium and radon together with the chemistry associated with equipment (such as nuclear reactors) which are designed to perform nuclear processes. Nuclear reactors can be distinghuished in two categories, the high flux reactor, primarily used for the creation of radio-active isotopes for medicinal or scientific use, and the low flux reactor, primarily used for power generation. Flux in this content meaning density of neutrons per unit of volume. These processes include the corrosion of surfaces and the behaviour under conditions of both normal and abnormal operation (such as during an accident). An important area is the behaviour of objects and materials after being placed into a waste store or otherwise disposed of.

- the study of the chemical effects resulting from the absorption of radiation within living animals, plants, and other materials. The radiation chemistry controls much of radiation biology as radiation has an effect on living things at the molecular scale, to explain it another way the raidation alters the biochemicals within an organism, the alteration of the biomolecules then changes the chemistry which occurs within the organism, this change in biochemistry then can lead to a biological outcome. As a result nuclear chemistry greatly assists the understanding of medical treatments (such as cancer radiotherapy) and has enabled these treatments to improve.

- the study of the production and use of radioactive sources for a range of processes. These include radiotherapy in medical applications; the use of radioactive tracers within industry, science and the environment; and the use of radiation to modify materials such as polymers[5][6] .

- the study and use of nuclear processes in non-radioactive areas of human activity. For instance, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy is commonly used in synthetic organic chemistry and physical chemistry and for structural analysis in macromolecular chemistry.

Early history

After the discovery of X-rays by Wilhelm Röntgen, many scientists began to work on ionizing radiation. One of these was Henri Becquerel, who investigated the relationship between phosphorescence and the blackening of photographic plates. When Becquerel (working in France) discovered that, with no external source of energy, the uranium generated rays which could blacken (or fog) the photographic plate, radioactivity was discovered. Marie Curie (working in Paris) and her husband Pierre Curie isolated two new radioactive elements from uranium ore. They used radiometric methods to identify which stream the radioactivity was in after each each chemical separation; they separated the uranium ore into each of the different chemical elements that were known at the time, and measured the radioactivity of each fraction. They then attempted to separate these radioactive fractions further, to isolate a smaller fraction with a higher specific activity (radioactivity divided by mass). In this way, they isolated polonium and radium. It was noticed in about 1901 that high doses of radiation could cause an injury in humans, Becquerel had carried a sample of radium in his pocket and as a result he suffered a high localised dose which resulted in a radiation burn[7] this injury resulted in the biological properties of radiation being investigated, which in time resulted in the development of medical treatments. Marie Curie's daughter (Irène Joliot-Curie) and her husband were the first to 'create' radioactivity: they bombarded boron with alpha particles to make a proton-rich isotope of nitrogen; this isotope emitted positrons.[8] In addition, they bombarded aluminium and magnesium with neutrons to make new radioisotopes.

Ernest Rutherford, working in Canada and England, showed that radioactivity decay can be described by a simple equation (a linear first degree derivative equation, now called first order kinetics), implying that a given radioactive substance has a characteristic "half life" (the time taken for the amount of radioactivity present in a source to diminish by half). He also coined the terms alpha, beta and gamma rays, he converted nitrogen into oxygen, and most importantly he supervised the students who did the Geiger-Marsden experiment (gold leaf experiment) which showed that the 'plum pudding model' of the atom was wrong. In the plum pudding model, proposed by J. J. Thomson in 1904, the atom is composed of electrons surrounded by a 'cloud' of positive charge to balance the electrons' negative charge. To Rutherford, the gold foil experiment implied that the positive charge was confined to a very small nucleus leading first to the Rutherford model, and eventually to the Bohr model of the atom, where the positive nucleus is surrounded by the negative electrons.

During the inital attempts to make the transuranium elements natural uranium was bombarded with neutrons, the idea was that by the creation of a neutron rich uranium isotope that the next element would be formed by beta decay. Instead in these early studys the fissile 235U underwent fission to generate the highly radioactive fission products. Due to their high activity these fission products (such as some of the shortlived barium isotopes) dominated the radiochemical anaylsis of the irradated uranium. At first it was thought that the uranium had been converted into radium (many of the early radiochemical methods have difficulty in distingishing between baroum and radium). But with time it was understood that the majority of the radioactivity was due to the products of breaking uranium nuclei into two fragements.Lise Meitner, Otto Robert Frisch (1939). "Disintegration of Uranium by Neutrons: a New Type of Nuclear Reaction". Nature 143: 239-240. DOI:10.1038/224466a0. Research Blogging. </ref>

Edwin McMillan attempted to measure the range of the fission products using cigarette paper, during this work he isolated a beta active isotope with a half life of 2.3 days (239Np). A short time later in 1940 plutinium was discovered

Main areas

Radiochemistry

Radiochemistry is the chemistry of radioactive materials, where radioactive isotopes of elements are used to study the properties and chemical reactions of non-radioactive isotopes (often within radiochemistry the absence of radioactivity leads to a substance being described as being inactive as the isotopes are stable).

For further details please see the page on radiochemistry.

Radiation chemistry

Radiation chemistry is the study of the chemical effects of radiation on matter; this is very different to radiochemistry as no radioactivity needs to be present in the material which is being chemically changed by the radiation. An example is the conversion of water into hydrogen gas and hydrogen peroxide.

Study of nuclear reactions

see also nuclear physics and nuclear reactions for further details.

A combination of radiochemistry and radiation chemistry is used to study nuclear reactions such as fission and fusion. Some early evidence for nuclear fission was the formation of a shortlived radioisotope of barium which was isolated from neutron irradiated uranium ( 139Ba, with a half-life of 83 minutes and 140Ba, with a half-life of 12.8 days, are major fission products of uranium). At the time, it was thought that this was a new radium isotope, as it was then standard radiochemical practice to use a barium sulphate carrier precipitate to assist in the isolation of radium.[9]. More recently, a combination of radiochemical methods and nuclear physics has been used to try to make new 'superheavy' elements; it is thought that islands of relative stability exist where the nuclides have half-lives of years, thus enabling weighable amounts of the new elements to be isolated. For more details of the original discovery of nuclear fission see the work of Otto Hahn.[1].

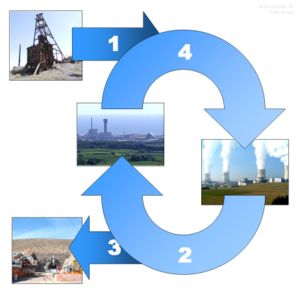

The nuclear fuel cycle

The chemistry associated with any part of the nuclear fuel cycle, including nuclear reprocessing. The fuel cycle includes all the operations involved in producing fuel, from mining, ore processing and enrichment to fuel production (Front end of the cycle). It also includes the 'in-pile' behaviour (use of the fuel in a reactor) before the back end of the cycle. The back end includes the management of the used nuclear fuel in either a cooling pond or dry storage, before it is disposed of into an underground waste store or reprocessed.

Normal and abnormal conditions

The nuclear chemistry associated with the nuclear fuel cycle can be divided into two main areas, one area is concerned with operation under the intended conditions while the other area is concerned with maloperation conditions where some alteration from the normal operating conditions has occured or (more rarely) an accident is occuring.

Reprocessing

Law

In the USA it is normal to use fuel once in a power reactor before placing it in a waste store. The long term plan is currently to place the civil used power reactor fuel in a deep store. This policy of not reporcessing was started in March 1977 for nuclear weapons proliferation reasons. The President Jimmy Carter issued a Presidential directive which indefinitely suspended the commercial reprocessing and recycling of plutonium in the USA. This Presidential directive is likely to have been an attempt by the USA to lead other countries by example, but many other nations continue to reprocess spent nuclear fuels. It is noteworthy that the goverment under Putin (President of Russia) repealed a law which had banned the inport of used nuclear fuel into Russia, this change in Russian law now permits the Russians to offer a reprocessing service for clients outside Russia (In a similar way to that offered by BNFL).

PUREX chemistry

The current method of choice is to use the PUREX liquid-liquid extraction process which uses a tributyl phosphate/hydrocarbon mixture to extract both uranium and plutonium from nitric acid. This extraction is of the nitrate salts and is classed as being of a solvation mechanism. For example the extraction of plutonium by a extraction agent (S) in a nitrate medium occurs by the following reaction.

Pu4+aq + 4NO3-aq + 2Sorganic --> [Pu(NO3)4S2]organic

A complex is formed between the metal cation, the nitrates and the tributyl phosphate, and a model compound of a dioxouranium(VI) complex with two nitrates and two triethyl phosphates has been characterised by X-ray crystalography.[2]

When the nitric acid concentration is high the extraction into the organic phase is favoured, and when the nitric acid concentration is low the extraction is reversed (the organic phase is stripped of the metal). It is normal to dissolve the used fuel in nitric acid, after the removal of the insoluble matter the uranium and plutonium are extracted from the highly active liquor. It is normal to then back extract the loaded organic phase to create a medium active liquor which contains mostly uranium and plutonium with only small traces of fission products. This medium active aqueous mixture is then extracted again by tributyl phosphate/hydrocarbon to form a new organic phase, the metal bearing organic phase is then stripped of the metals to form an aqueous mixture of only uranium and plutonium. The two stages of extraction are used to improve the purity of the actinide product, the organic phase used for the first extraction will suffer a far greater dose of radiation. The radiation can degrade the tributyl phosphate into dibutyl hydrogen phosphate. The dibutyl hydrogen phosphate can act as an extraction agent for both the actinides and other metals such as ruthenium. The dibutyl hydrogen phosphate can make the system behave in a more complex manner as it tends to extract metals by an ion exchange mechanism (extraction favoured by low acid concentration), to reduce the effect of the dibutyl hydrogen phosphate it is common for the used organic phase to be washed with sodium carbonate solution to remove the acidic degradation products of the tributyl phosphate.

DUPIC (an alternative)

As an alternative to the use of normal uranium in a CANDU it has been suggested that the spent fuel from a PWR could be used in place of naturial uranium in a heavy water moderated CANDU. The term DUPIC means Direct Use of spent Preasureised water reactor fuel In CANDU.[10][11] A discussion of different fuel cycles has been published, this includes a duiscussion of the DUPIC idea.Cite error: Closing </ref> missing for <ref> tag[12]. A short review of the biochemical properties of a series of key long lived radioisotopes can be read on line.[13]

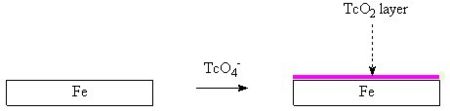

It is important to note that 99Tc in nuclear waste may exist in chemical forms other than the 99TcO4 anion, these other forms have different chemical properties.[14]

Similarly, the release of iodine-131 in a serious power reactor accident could be retarded by absorption on metal surfaces within the nuclear plant. [3]

Spinout areas

Some methods first developed within nuclear chemistry and physics have become so widely used within chemistry and other physical sciences that they may be best thought of as separate from normal nuclear chemistry. For example, the isotope effect is used so extensively to investigate chemical mechanisms and the use of cosmogenic isotopes and long-lived unstable isotopes in geology that it is best to consider much of isotopic chemistry as separate from nuclear chemistry.

Kinetics (use within mechanistic chemistry)

The mechanisms of chemical reactions can be investigated by observing how the kinetics of a reaction are changed by making an isotopic modification of a substrate. This is now a standard method in organic chemistry. Briefly, replacing normal hydrogens (protons) by deuteriumwithin a chemical compound causes the rate of molecular vibration (C-H, N-H and O-H bonds show this) to decrease. This then can lead to a decrease in the reaction rate if the rate-determining step involves breaking a bond between hydrogen and another atom. Thus, if the reaction changes in rate when protons are replaced by deuteriums, it is reasonable to assume that the breaking of the bond to hydrogen is part of the step which determines the rate.

Uses within geology, biology and forensic science

Cosmogenic isotopes are formed by the interaction of cosmic rays with the nucleus of an atom. These can be used for dating purposes and for use as natural tracers. In addition, by careful measurement of some ratios of stable isotopes it is possible to obtain new insights into the origin of bullets, ages of ice samples, ages of rocks, and the diet of a person can be identified from a hair or other tissue sample. (See Isotope geochemistry and Isotopic signature for further details).

Biology

Within living things, isotopic labels (both radioactive and nonradioactive) can be used to probe how the complex web of reactions which makes up the metabolism of an organism converts one substance to another. For instance a green plant uses light energy to convert water and carbon dioxide into glucose by photosynthesis. If the oxygen in the water is labeled, then the label appears in the oxygen gas formed by the plant and not in the glucose formed in the chloroplasts within the plant cells.

For biochemical and physiological experiments and medical methods, a number of specific isotopes have important applications.

- Stable isotopes have the advantage of not delivering a radiation dose to the system being studied; however, significant an excess of them in the organ or organisms might still interfere with its functioning, and the availability of sufficient amounts for whole-animal studies is limited for many isotopes. Measurement is also difficult, and ususally requires mass spectroscopy to determine how much of the isotope is present in particular compounds, and there is no means of localizing measurements within the cell.

- H-2 (deuterium), the stable isotope of hydrogen, is a stable tracer, the concentration of which can be measured by mass spectroscopy or NMR. It is incorporated into all cellular structures. Specific deuterated compound can also be produced.

- N-15 the stable isotope of nitrogen, has also been used. It is incorporated mainly into proteins.

- Radioactive isotopes have the advantages of being detectable in very low quantities, in being easily measured by scintillation counting or other radiochemical methods, and in being localizable to particular regions of a cell, and quantifiable by autoradiography. Many compounds with the radioactive atoms in specific positions can be prepared, and are widely available commercially. In high quantities they require precautions to guard the workers from the effects of radiation--and they can easily contaminate laboratory glassware and other equipment. For some isotopes the half-life is so short that preparation and measurement is difficult.

By organic synthesis it is possible to create a complex molecule with a radioactive label that can be confined to a small area of the molecule. For short-lived isotopes such as 11C, very rapid synthetic methods have been developed to permit the rapid addition of the radioactive isotope to the molecule. For instance a palladium catalysed carbonylation reaction in a microfluidic device has been used to rapidly form amides[4] and it might be possible to use this method to form radioactive imaging agents for PET imaging.[15]

- 3H, Tritium, the radioisotope of hydrogen, it available at very high specific activities, and compounds with this isotope in particular positions are easily prepared by standard chemical reactions such as hydrogenation of unsaturated precursors. The isotope emits very soft beta radiation, and can be detected by scintillation counting.

- 11C, Carbon-11 can be made using a cyclotron, boron in the form of boric oxide is reacted with protons in a (p,n) reaction. An alternative route is to react 10B with deuterons. By rapid organic synthesis, the 11C compound formed in the cyclotron is converted into the imaging agent which is then used for PET.

- 14C, Carbon-14 can be made (as above), and it is possible to convert the target material into simple inorganic and organic compounds. In most organic synthesis work it is normal to try to create a product out of two approximately equal sized fragments and to use a convergent route, but when a radioactive label is added, it is normal to try to add the label late in the synthesis in the form of a very small fragment to the molecule to enable the radioactivity to be localised in a single group. Late addition of the label also reduces the number of synthetic stages where radioactive material is used.

- 18F, fluorine-18 can be made by the reaction of neon with deuterons, 20Ne reacts in a (d,4He) reaction. It is normal to use neon gas with a trace of stable flourine (19F2). The 19F2 acts as a carrier which increases the yield of radioactivity from the cyclotron target by reducing the amount of radioactivity lost by absorption on surfaces. However, this reduction in loss is at the cost of the specfic activity of the final product.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR)

NMR spectroscopy uses the net spin of nuclei in a substances upon energy absorption to identify molecules. This has now become a standard spectroscopic tool within synthetic chemistry. One major use of NMR is to determine the bond connectivity within an organic molecule.

NMR imaging also uses the net spin of nuclei (commonly protons) for imaging. This is widely used for diagnostic purposes in medicine, and can provide detailed images of the inside of a person without inflicting any radiation upon them. In a medical setting, NMR is often known simply as "magnetic resonance" imaging, as the word 'nuclear' has negative connotations for many people.

References

- ↑ Meitner L, Frisch OR (1939) Disintegration of uranium by neutrons: a new type of nuclear reaction Nature 143:239-240 [1]

- ↑ J.H. Burns, "Solvent-extraction complexes of the uranyl ion. 2. Crystal and molecular structures of catena-bis(.mu.-di-n-butyl phosphato-O,O')dioxouranium(VI) and bis(.mu.-di-n-butyl phosphato-O,O')bis[(nitrato)(tri-n-butylphosphine oxide)dioxouranium(VI)]", Inorganic Chemistry, 1983, 22, 1174-1178

- ↑ Glänneskog H (2004) Interactions of I2 and CH3I with reactive metals under BWR severe-accident conditions Nuclear Engineering and Design 227:323-9

- ↑ Miller PW et al (2006) Chemical Communications 546-548

Text books

- Radiochemistry and Nuclear Chemistry

Comprehensive textbook by Choppin, Liljenenzin and Rydberg. ISBN -0750674636, Butterworth-Heinemann, 2001 [16].

- Radioactivity, Ionizing radiation and Nuclear Energy

Basic textbook for undergraduates by Jiri Hála and James D Navratil. ISBN -807302053-X, Konvoj, Brno 2003 [17]

- The Radiochemical Manual

Overview of the production and uses of both open and sealed sources. Edited by BJ Wilson and written by RJ Bayly, JR Catch, JC Charlton, CC Evans, TT Gorsuch, JC Maynard, LC Myerscough, GR Newbery, H Sheard, CBG Taylor and BJ Wilson. The radiochemical centre (Amersham) was sold via HMSO, 1966 (second edition)