Radiation chemistry

Radiation chemistry is a subdivision of nuclear chemistry which is the study of the chemical effects of radiation on matter; this is very different to radiochemistry as no radioactivity needs to be present in the material which is being chemically changed by the radiation. An example is the conversion of water into hydrogen gas and hydrogen peroxide.

Reduction of organics by solvated electrons

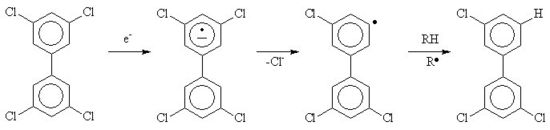

A recent area of work has been the destruction of toxic organic compounds by irradiation [1]; after irradiation, "dioxins" (polychlorodibenzo-p-dioxins) are dechloroinated in the same way as PCBs can be converted to biphenyl an inorganic chloride. This is because the solvated electrons react with the organic compound to form a radical anion, which decomposes by the loss of a chloride anion. If a deoxygenated mixture of PCBs in isopropanol or mineral oil is irradiated with gamma rays, then the PCBs will be dechlorinated to form inorganic chloride and biphenyl. The reaction works best in isopropanol if potassium hydroxide (caustic potash) is added. The base deprotonates the hydroxydimethylmethyl radical to be converted into acetone and a solvated electron, as the result the G value (yield for a given energy due to radiation deposited in the system) of chloride can be increased because the radiation now starts a chain reaction, each solvated electron formed by the action of the gamma rays can now convert more than one PCB molecule.[2][3]If oxygen, acetone, nitrous oxide, sulfur hexafluoride or nitrobenzene[4] is present in the mixture, then the reaction rate is reduced. This work has been done recently in the USA, often with used nuclear fuel as the radiation source.[2][3]

In addition to the work on the destruction of aryl chlorides it has been shown that aliphatic chlorine and bromine compounds such as perchloroethylene,[5] Freon (1,1,2-trichloro-1,2,2-trifluoroethane) and halon-2402 (1,2-dibromo-1,1,2,2-tetrafluoroethane) can be dehalogenated by the action of radiation on alkaline isopropanol solutions. Again a chain reaction has been reported.[6]

In addition to the work on the reduction of organic compounds by irradation, some work on the radiation induced oxidation of organic compounds has been reported. For instance the use of radiogenic hydrogen peroxide (formed by irradation) to remove sulfur from coal has been reported. In this study it was found that the addition of manganese dioxide to the coal increased the rate of sulfur removal.[7] The degradation of nitrobenzene under both reducing and oxidising conditions in water has been reported.[8]

Reduction of metal compounds

In addition to the reduction of organic compounds by the solvated electrons it has been reported that upon irradation a pertechnetate solution, at pH 4.1 is converted to a colloid of technetium dioxide. Irradation of a solution at pH 1.8 soluble Tc(IV) complexes are formed. Irradation of a solution at 2.7 forms a mixture of the colloid and the soluble Tc(IV) compounds.[9] Gamma irradation has been used in the synthesis of nanoparticles of gold on iron oxide (Fe2O3).[4][10]

It has been shown that the irradation of aqueous solutions of lead compounds leads to the formation of elemental lead, when an inorganic solid such as bentonite and sodium formate are present then the lead is removed from the aqueous solution.[11]

Polymer modifcation

Another key area uses radiation chemistry to modify polymers. Using radiation, it is possible to convert monomers to polymers, to crosslink polymers, and to break polymer chains[5][6]. Both man-made and natural polymers (such as carbohydrates [7]) can be processed in this way.

Water chemistry

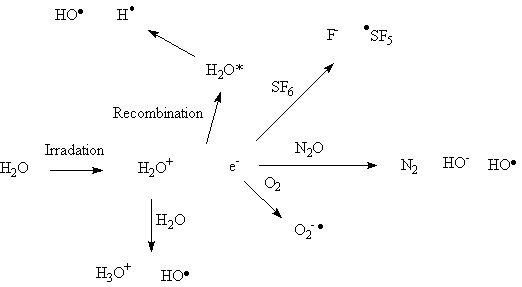

Both the harmful effects of radiation upon biological systems (induction of cancer and acute radiation injuries) and the useful effects of radiotherapy involve the radiation chemistry of water. The vast majority of biological molecules are present in an aqueous medium; when water is exposed to radiation, the water absorbs energy, and as a result forms chemically reactive species that can interact with dissolved substances (solutes). Water is ionized to form a solvated electron and H2O+, the H2O+ cation can react with water to form a hydrated proton (H3O+) and a hydroxyl radical (HO.). Furthermore, the solvated electron can recombine with the H2O+ cation to form an excited state of the water, this excited state then decomposes to species such as hydroxyl radicals (HO.), hydrogen atoms (H.) and oxygen atoms (O.). Finally, the solvated electron can react with solutes such as solvated protons or oxygen molecules to form respectively hydrogen atoms and dioxygen radical anions. The fact that oxygen changes the radiation chemistry might be one reason why oxygenated tissues are more sensitive to irradiation than the deoxygenated tissue at the centre of a tumor. The free radicals, such as the hydroxyl radical, chemically modify biomolecules such as DNA, leading to damage such as breaks in the DNA strands. Some substances can protect again radiation-induced damage by reacting with the reactive species generated by the irradiation of the water. (See Oxidative stress)

It is important to note that the reactive species generated by the radiation can take part in following reactions, this is similar to the idea of the non-electrochemical reactions which follow the electrochemical event which is observed in cyclic voltammetry when a non-reversible event occurs. For example the SF5 radical formed by the reaction of solvated electrons and SF6 undergo further reactions which lead to the formation of hydrogen fluoride and sulfuric acid.[12]

In water the dimerisation reaction of hydroxyl radicals can form hydrogen peroxide, in saline systems the reaction of the hydroxyl radicals with chloride anions form hypochlorite anions.

It has been suggested that the action of radiation upon underground water is responsible for the formation of hydrogen which was converted by bacteria into methane.[8][13]. A series of papers on the subject of bateria living under the surface of the earth which are fed by the hydrogen generated by the radiolysis of water can be read on line.[9]

Equipment

Industrial processing equipment

To process materials, either a gamma source or an electron beam can be used. The international type IV (wet storage) irradiator is a common design (the JS6300 and JS6500 gamma sterilizers (made by 'Nordion International'[10], which used to trade as 'Atomic Energy of Canada Ltd') are typical. [14]. In these irradiation plants, the source is stored in a deep well filled with water when not in use. When the source is required, it is moved by a steel wire to the irradiation room where the products which are to be treated are present; these objects are placed inside boxes which are moved through the room by an automatic mechanism. By moving the boxes from one point to another, the contents are given a uniform dose. After treatment, the product is moved by the automatic mechanism out of the room. The irradiation room has very thick concrete walls (about 3m thick) to prevent gamma rays from escaping. The source consists of 60Co rods sealed within two layers of stainless steel, the rods are combined with inert dummy rods to form a rack with a total activity of about 12.6PBq (340kCi).

Research equipment

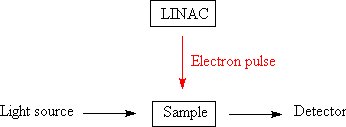

While it is possible to do some types of research using an irradiator much like that used for gamma sterilization, it is common in some areas of science to use a time resolved experiment where a material is subjected to a pulse of radiation (normally electrons from a LINAC. After the pulse of radiation, the concentration of different substances within the material are measured by emission spectroscopy or Absorption spectroscopy, hence the rates of reactions can be determined. This allows the relative abilities of substances to react with the reactive species generated by the action of radiation on the solvent (commonly water) to be measured. This experiment is known as pulse radiolysis[11] which is closely related to Flash photolysis.

In the latter experiment the sample is excited by a pulse of light to examine the decay of the excited states by [[spectroscopy] [[12]]; sometimes the formation of new compounds can be investigated.[15][13] Flash photolysis experiments have led to a better understanding of the effects of halogen-containing compounds upon the ozone layer.[14]

References

- ↑ Zhao C et al (2007) Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 76:37-45

- ↑ Ajit Singh and Walter Kremers, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2002, 65(4-5), 467-472

- ↑ Bruce J. Mincher, Richard R. Brey, René G. Rodriguez, Scott Pristupa and Aaron Ruhter, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2002, 65(4-5), 461-465

- ↑ A. G. Bedekar, Z. Czerwik and J. Kroh, "Pulse radiolysis of ethylene glycol and 1,3-propanediol glasses—II. Kinetics of trapped electron decay", 1990, 36, 739-742

- ↑ V. Múka, *, R. Silber, M. Pospíil, V. Kliský and B. Bartoníek, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 1999, 55(1), 93-97

- ↑ Seiko Nakagawa and Toshinari Shimokawa, Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2002, 63(2), 151-156

- ↑ P. S. M. Tripathi, K. K. Mishra, R. R. P. Roy and D. N. Tewari, "γ-Radiolytic desulphurisation of some high-sulphur Indian coals catalytically accelerated by MnO2", Fuel Processing Technology, 2001, 70, 77-96

- ↑ Shao-Hong Feng, Shu-Juan Zhang, Han-Qing Yu, and Qian-Rong Li, "Radiation-induced Degradation of Nitrobenzene in Aqueous Solutions", Chemistry Letters, 2003, 32(8), 718

- ↑ T. Sekine, H. Narushima, T. Suzuki, T. Takayama, H. Kudo, M. Lin and Y. Katsumura, Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects, 2004, 249(1-3), 105-109

- ↑ Satoshi Seino, Takuya Kinoshita, Yohei Otome, Kenji Okitsu, Takashi Nakagawa, and Takao A. Yamamoto, "Magnetic Composite Nanoparticle of Au/γ-Fe2O3 Synthesized by Gamma-Ray Irradiation ", Chemistry Letters, 2003, 32(8), 690

- ↑ M. Pospίšil, V. Čuba, V. Múčka and B. Drtinová, "Radiation removal of lead from aqueous solutions- effects of various sorbants and nitrous oxide", Radiation Physics and Chemistry, 2006, 75, 403-407

- ↑ K.-D. Asmus and J.H. Fendler, "The reaction of sulfur hexafluoride with solvated electrons", The Journal of Physical Chemistry, 1968, 72, 4285-4289

- ↑ LI-HUNG LIN, GREG F. SLATER, BARBARA SHERWOOD LOLLAR, GEORGES LACRAMPE-COULOUME and T. C. ONSTOTT, Geochimica et Cosmochimica Acta, 2005, 69, 893-903.

- ↑ Features of the design are discussed in the IAEA report on a human error accident in such an irradiation plant [1]

- ↑ George Porter, Nobel lecture, 11 December 1967