Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz m (→Early career) |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

||

| Line 225: | Line 225: | ||

| publisher = Random House | year = 1992}}, pp. 282-283</ref> | | publisher = Random House | year = 1992}}, pp. 282-283</ref> | ||

In 1992, at the [[Command and General Staff College]] of the [[U.S. Army]], [[lieutenant colonel]] Boyd M. Lewis wrote a new edition of the Army's ''Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership''. Unfortunately, Lewis died days after publication, so he could not be asked why he picked Chamberlain and [[George | In 1992, at the [[Command and General Staff College]] of the [[U.S. Army]], [[lieutenant colonel]] Boyd M. Lewis wrote a new edition of the Army's ''Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership'', describing the Little Round Top action in terms relevant to contemporary officer training.<blockquote>On Little Round Top, COL Chamberlain told his company commanders the purpose and importance of their mission. He ordered the right flank company to tie in with the 83d Pennsylvania and the left flank company to anchor on a large boulder. His thoughts turned to his left flank. There was nothing there except a small hollow and the rising slope of Big Round Top. The 20th Maine was literally at the end of the line.</blockquote> | ||

<blockquote> | |||

COL Chamberlain then showed a skill common to good tactical leaders. He imagined threats to his unit, did what he could to guard against them, and considered what he would do to meet other possible threats. Since his left flank was open, COL Chamberlain sent B Company, commanded by CPT Walter G. Morrill, off to guard it and "act as the necessities of battle required." The captain positioned his men behind a stone wall that would face the flank of any Confederate advance. There, fourteen soldiers from the 2d US Sharpshooters, who had been separated from their unit, joined them. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The 20th Maine had been in position only a few minutes when the soldiers of the 15th and 47th Alabama attacked. The Confederates had also marched all night and were tired and thirsty. Even so, they attacked ferociously. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

The Maine men held their ground, but then one of COL Chamberlain’s officers reported seeing a large body of Confederate soldiers moving laterally behind the attacking force. COL Chamberlain climbed on a rock—exposing himself to enemy fire—and saw a Confederate unit moving around his exposed left flank. If they outflanked him, his unit would be pushed off its position and destroyed. He would have failed his mission. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote> | |||

COL Chamberlain had to think fast. The tactical manuals he had so diligently studied called for a maneuver that would not work on this terrain. The colonel had to create a new maneuver, one that his soldiers could execute, and execute now. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote>...The decision left COL Chamberlain with another problem: there was nothing in the tactics book about how to get his unit from their L-shaped position into a line of advance. Under tremendous fire and in the midst of the battle, COL Chamberlain again called his commanders together. He explained that the regiment’s left wing would swing around "like a barn door on a hinge" until it was even with the right wing. Then the entire regiment, bayonets fixed, would charge downhill, staying anchored to the 83d Pennsylvania on its right. The explanation was clear and the situation clearly desperate. | |||

</blockquote> | |||

<blockquote>When COL Chamberlain gave the order, 1LT Holman Melcher of F Company leaped forward and led the left wing downhill toward the surprised Confederates. COL Chamberlain had positioned himself at the boulder at the center of the L. When the left wing was abreast of the right wing, he jumped off the rock and led the right wing down the hill. The entire regiment was now charging on line, swinging like a great barn door—just as its commander had intended.<ref>{{citation | |||

| url = https://rdl.train.army.mil/soldierPortal/atia/adlsc/view/restricted/9502-1/fm/22-100/ch1.htm;jsessionid=cc0KL5tL15nnJrrl30pb51t4znyszMbZ57J5BQj6cNfF70PHJLnh!79752089 | |||

| title = Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership | |||

| contribution = CHAPTER 1: The Army Leadership Framework | |||

| publisher = [[U.S. Army]]}}</ref></blockquote>Unfortunately, Lewis died days after publication, so he could not be asked why he picked Chamberlain and [[George Patton]]. It suprises many that the two had many common traits, and surprises more that the two successful military leaders were so different in so many ways. <ref>Pullen, pp. 179-183</ref> | |||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

Revision as of 14:11, 12 June 2010

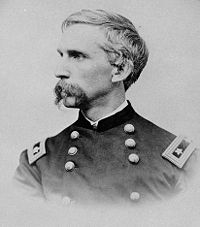

Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, usually called "Lawrence", (1828-1914) was an American educator, who taught in a wide variety of fields, but was also an exceptionally distinguished citizen-soldier in the American Civil War. At Appomattox Court House, he was given the honor of accepting the Confederate flags, but did so, without orders, in a way that started healing for both sides.

He was an emotionally complex man, but widely respected as a self-made war hero, a creative and beloved educator, and an elected official and political appointee without the right sort of personality for politics.

Early life

Brought up on his parents' farm, his father wanted him to join the military while his mother aimed him for the clergy. Since he chose to attend Bowdoin College, which, at the time, had a strong Congregationalist influence, perhaps his mother had the last word.

Before attending Bowdoin, he had to meet a requirement of proficiency in the Greek language, so, already having learned French and Latin, he taught himself Greek and was accepted. He was a respected general student, and also a musician, who taught voice, led choirs, and played the bass viola.[1]

While attending Bowdoin, he attended the First Parish Church, falling in love with the minister's daughter, Fanny. After his graduation, he enrolled in Bangor Theological Seminary, but stayed in contact with Fanny. At the seminary, his languages expanded to German, Arabic, Hebrew and Syriac. Few pictures of Fanny survive, but accounts describe her as much more strikingly attractive than the pictures, and a theme of romantic physicality was evident in their correspondence.

He joined the Bowdoin College faculty in 1856, first with a professorship in logic and natural theology, then adding rhetoric and oratory, and eventually professor of modern languages. Early in his career, he developed a distinct philosophy of education:

My idea of a College course is that it should afford a liberal education - not a special or professional one, not in any way one-sided. It cannot be a finished education, but should be, I think, a general outline of a symmetrical development, involving such acquaintance with all the departments of knowledge and culture - proportionate to their several values - as shall give some insight into the principles and powers by which thought passes into life - together with such practice and exercise in each of the great fields of study that the student may experience himself a little in all.[2]

In spite of objections from her father, he married Fanny, starting a what was generally considered a lifelong love affair.[3] They had five children, two of whom survived into adulthood. Another historian, however, suggests their marriage may have had problems; [4] there clearly was a confrontation in 1868.

American Civil War

Volunteering for service in 1862, he declined, initially, a regimental command. He became lieutenant colonel of the 20th Maine Regiment, taking command in May 1863, and was promoted to colonel on August 8. His brother Tom also served in the regiment, as a junior officer.

He fought with the 20th at the Battles of Antietam, Shepherdstown Ford, Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville. He suffered his first wound at Fredericksburg.

Little Round Top

For performance in combat, however, he is most remembered for the Battle of Gettysburg, and the Little Round Top engagement. Immediately prior to the battle, he faced the difficult command task of speaking to soldiers, accused of mutiny, whose enlistments in the 2nd Maine had expired, but who were involuntarily assigned to the 20th. "Chamberlain's brief speech and his pledge to plead their case caused all but a handful to take arms and join the ranks of the 20th for the coming battle".

At Little Round Top, the 20th held the end of the Union flank, in a desperate defense ending in an all-out bayonet charge against the 15th Alabama Regiment. Indeed, it was tactically critical; it has also become a legend in American military history; Chamberlain was to become a key character in Michael Shaara's historical novel The Killer Angels, the basis for a number of books, continued by Shaara's son, and for the Turner Broadcasting film and miniseries, in which he was played by Jeff Daniels. The character of his sergeant, Buster Kilrain, was fictional, but the Shaara material is highly regarded.

Not a moment was about to be lost! Five minutes more of such a defensive and the last roll call would sound for us! Desperate as the chances were, there was nothing for it but to take the offensive. I stepped to the colors. The men turned towards me. One word was enough- 'BAYONETS!' It caught like fire and swept along the ranks. The men took it up with a shout, one could not say whether from the pit or the song of the morning sat, it was vain to order 'Forward!'. No mortal could have heard it in the mighty hosanna that was winging the sky. The whole line quivered from the start; the edge of the left-wing rippled, swung, tossed among the rocks, straightened, changed curve from scimitar to sickle-shape; and the bristling archers swooped down upon the serried host- down into the face of half a thousand! Two hundred men![5]

There have been some suggestions that one of his junior officers originally started the bayonet charge, but there is little question Chamberlain committed all his forces to it, and was wounded in combat.

Petersburg

In November 1863 he was relieved from field service and sent to Washington suffering from malaria, the eventual cause of his death. He returned to the 20th, commanding it in the First Battle of Cold Harbor and the Battle of Petersburg, in which he was wounded; Ulysses S. Grant spot-promoted him to brigadier general, although he was expected to die.

The wound suffered at Petersburg damaged his bladder and urethra. In surgery later called "miraculous" by a U.S. Army surgeon in 1997, two regimental surgeon went into his abdomen, almost a death sentence by infection in 1864, and repaired the damage. The technology available for urethral repair was very limited, and he required repeated surgeries for what probably partially impaired his sexual function. Normally, this detail would be outside the scope of a historical article, but it may have been an contributing factor to tension with his wife while Governor. [6]

Higher command

He returned to brigade command in November, and fought in the Overland Campaign in the Battles of the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, North Anna and Second Petersburg. Wounded at the Rives' Salient engagement at Second Petersburg, he was again expected to die, and again spot-promoted by Grant, this time to major general. By the final days, he led a division.

A time to heal

At Appomattox Court House, he was given the honor, a sad one, of accepting the formal surrender of Confederate troops. As Confederate Gen. John Gordon's troops passed, Chamberlain, without orders, called his troops to attention and gave formal recognition to fellow soldiers, fellow citizens again. This was long remembered as a healing act, about which Chamberlain wrote in the lengthy Passing of the Armies.

I resolved to mark it by some token of recognition, which could be no other than a salute of arms. Well aware of the responsibility assumed, and of the criticisms that would follow, as the sequel proved, nothing of that kind could move me in the least. The act could be defended, if needful, by the suggestion that such a salute was not to the cause for which the flag of the Confederacy stood, but to its going down before the flag of the Union. My main reason, however, was one for which I sought no authority nor asked forgiveness. Before us in proud humiliation stood the embodiment of manhood: men whom neither toils and sufferings, nor the fact of death, nor disaster, nor hopelessness could bend from their resolve; standing before us now, thin, worn, and famished, but erect, and with eyes looking level into ours, waking memories that bound us together as no other bond; — was not such manhood to be welcomed back into a Union so tested and assured?

...Gordon at the head of the column, riding with heavy spirit and downcast face, catches the sound of shifting arms, looks up, and, taking the meaning, wheels superbly, making with himself and his horse one uplifted figure, with profound salutation as he drops the point of his sword to the boot toe; then facing to his own command, gives word for his successive brigades to pass us with the same position of the manual, — honor answering honor. On our part not a sound of trumpet more, nor roll of drum; not a cheer, nor word nor whisper of vain-glorying, nor motion of man standing again at the order, but an awed stillness rather, and breath-holding, as if it were the passing of the dead!

As each successive division masks our own, it halts, the men face inward towards us across the road, twelve feet away; then carefully "dress" their line, each captain taking pains for the good appearance of his company, worn and half starved as they were. The field and staff take their positions in the intervals of regiments; generals in rear of their commands. They fix bayonets, stack arms; then, hesitatingly, remove cartridge-boxes and lay them down. Lastly, — reluctantly, with agony of expression, — they tenderly fold their flags, battle-worn and torn, blood-stained, heart-holding colors, and lay them down; some frenziedly rushing from the ranks, kneeling over them, clinging to them, pressing them to their lips with burning tears. And only the Flag of the Union greets the sky! [7]

While this gained him status on a national level, it was later to throw question on him when he later entered Republican politics in Maine. No one with secret sympathies for the South could be trusted by the Radical Republicans that controlled the Maine party.[8]

Postwar and politics

He rode in the formal end-of-war review, ended his service in August 1865, although he was reactivated so he could receive surgery for his war wounds. While he returned to the Bowdoin faculty, he also began to lecture about the Civil War. In August 1865, Grant made a visit to the Bowdoin commencement and stayed at Chamberlain's home. The visit was one of a number by Grant, which suggested a campaign tour, but the obvious endorsement of Chamberlain by Grant suggested he could be a strong Republican candidate for governor. Grant had principally come, however, not to meet with Chamberlain, but with O.O. Howard, another retired general and head of the Freedmen's Bureau[9] Maine's Republican leader, James G. Blaine, first saw Chamberlain as a strong gubernatorial candidate: a popular war hero who rose by his abilities, and came from a part of Maine that most avoided regional dislikes. Blaine, however, did not know Chamberlain's political weaknesses: "He did not have the skill necessary to move easily and gracefully out of difficult or embarrassing situations. Although adept at self-promotion in many ways, he would later shrink from initiating and running a political campaign in his own behalf. He lacked the thick, protective, rhinoceros hide that a poltician needs. And where matters of principle were concerned, he had little talent for compromise...he would speak and act according to his own beliefs."[10]

Shortly afterward, their seven-month-old daughter died, the third child to die in infancy. For their tenth wedding anniversary on December 7, 1865, he gave her a bracelet that has become an artifact of American jewelers, centered about the insignia of the corps he commanded, with inscriptions of his battles and the shoulder boards of his rank. The marriage, however, was strained by the time he had spent away, the death of a child, and his continuing pain and restlessness from his wound. Chamberlain chose to run for Governor of Maine as a new adventure, without her agreement. [11] Well after the war, Congress explicitly voted him the Medal of Honor; it was not one of the questionable awards that did not meet the modern standards of the Pyramid of Honor. He was also governor of Maine, but his beloved Bowdoin College was first in his heart.

As governor

The long wartime separation from Fanny introduced tensions into their marriage, exacerbated by the political career in which she had no role. On November 19, 1868, a member of his staff in the Governor's Mansion told him that Fanny was telling neighbors he was pulling her hair and striking her, and she was planning to sue for divorc. The next day, he wrote a manuscript letter in the Bowdoin collection talking not about the specific allegations but the situation. It appeared to lead to reconciliation three years later back at Bowdoin. [12] A friend suggested she was preparing for divorce, to which Chamberlain responded, "The thing comes to this, if you are contemplating any such things as Mr Johnson says—there is a better way to do it. If you are not, you must see the gulf of misery to which this confidence with unworthy people tends. You have this advantage of me, that I never spoke unkindly of you to any person. I shall not now do so to you. But it is a very great trial to me—more than all things else put together—wounds, pains, toils, wrongs, + hatred of eager enemies" [13] During her later years, Fanny, who had been an artist in her youth, became more isolated as she lost her sight.

Return to Bowdoin

He preferred education to politics, and in 1871 became president of Bowdoin College. At a 2003 dedication of a memorial to him, the current college president, Barry Mills as "'thankless and wasteful'." Hardly the feelings of a man who felt appreciated, but also hardly the feelings of anyone assembled here today!" Bowdoin, a small but influential school, in Mills' words, "can trace much of its modern identity to the controversial Chamberlain presidency."

Even though it was a competitor, Chamberlain was instrumental in forming the University of Maine.

Chamberlain took a college steeped in the traditions of a classical curriculum and urged it to consider practical and technical education. In his inaugural address he pushed the College to "...accept immediately the challenge of the times," by placing a new emphasis on science and by replacing Greek and Latin with French and German. In the same speech, Chamberlain had the audacity to suggest that women too should "...have part in [the] high calling" represented by a Bowdoin education - an "innovation" that would take another century to materialize.

As president, Chamberlain set out to reform the strict and outdated student code of discipline. He eliminated mandatory morning and evening prayers and Saturday classes. He encouraged the faculty to be more accessible to students both inside and outside the classroom. And he established something near and dear to the hearts of each of his successors: an endowment for the College. where he restructured the college curriculum to include science and engineering.[14]

U.S. Army Legacy

A descendant, Bill Chamberlain, commanded a U.S. Army battalion in the Gulf War in 1990. In its preparation for the assault, MG Barry McCaffrey had taken the senior commanders of the 24th Mechanizing through an exhausting 36 hour command post map exercise ("Map-Ex"), which left them knowing their plans perfectly. Still, it was tiring; told McCaffrey: "Sir, I just want to say I would rather be shot in combat than go through another Map-Ex." A fellow battalion commander agreed, "I, too, would rather see Bill shot than go through another Map-Ex." [15]

In 1992, at the Command and General Staff College of the U.S. Army, lieutenant colonel Boyd M. Lewis wrote a new edition of the Army's Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership, describing the Little Round Top action in terms relevant to contemporary officer training.

On Little Round Top, COL Chamberlain told his company commanders the purpose and importance of their mission. He ordered the right flank company to tie in with the 83d Pennsylvania and the left flank company to anchor on a large boulder. His thoughts turned to his left flank. There was nothing there except a small hollow and the rising slope of Big Round Top. The 20th Maine was literally at the end of the line.

COL Chamberlain then showed a skill common to good tactical leaders. He imagined threats to his unit, did what he could to guard against them, and considered what he would do to meet other possible threats. Since his left flank was open, COL Chamberlain sent B Company, commanded by CPT Walter G. Morrill, off to guard it and "act as the necessities of battle required." The captain positioned his men behind a stone wall that would face the flank of any Confederate advance. There, fourteen soldiers from the 2d US Sharpshooters, who had been separated from their unit, joined them.

The 20th Maine had been in position only a few minutes when the soldiers of the 15th and 47th Alabama attacked. The Confederates had also marched all night and were tired and thirsty. Even so, they attacked ferociously.

The Maine men held their ground, but then one of COL Chamberlain’s officers reported seeing a large body of Confederate soldiers moving laterally behind the attacking force. COL Chamberlain climbed on a rock—exposing himself to enemy fire—and saw a Confederate unit moving around his exposed left flank. If they outflanked him, his unit would be pushed off its position and destroyed. He would have failed his mission.

COL Chamberlain had to think fast. The tactical manuals he had so diligently studied called for a maneuver that would not work on this terrain. The colonel had to create a new maneuver, one that his soldiers could execute, and execute now.

...The decision left COL Chamberlain with another problem: there was nothing in the tactics book about how to get his unit from their L-shaped position into a line of advance. Under tremendous fire and in the midst of the battle, COL Chamberlain again called his commanders together. He explained that the regiment’s left wing would swing around "like a barn door on a hinge" until it was even with the right wing. Then the entire regiment, bayonets fixed, would charge downhill, staying anchored to the 83d Pennsylvania on its right. The explanation was clear and the situation clearly desperate.

When COL Chamberlain gave the order, 1LT Holman Melcher of F Company leaped forward and led the left wing downhill toward the surprised Confederates. COL Chamberlain had positioned himself at the boulder at the center of the L. When the left wing was abreast of the right wing, he jumped off the rock and led the right wing down the hill. The entire regiment was now charging on line, swinging like a great barn door—just as its commander had intended.[16]

Unfortunately, Lewis died days after publication, so he could not be asked why he picked Chamberlain and George Patton. It suprises many that the two had many common traits, and surprises more that the two successful military leaders were so different in so many ways. [17]

References

- ↑ Joshua Chamberlain - Maine's Favorite Son, Wicked Good Maine

- ↑ (Letter) Joshua L. Chamberlain to Nehemiah Cleaveland,, Bowdoin College Digital Archive, 14 October 1859

- ↑ Jeremiah E. Goulka and James M. McPherson, ed. (2003), The Grand Old Man of Maine: Selected Letters of Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, 1865-1914, University of North Carolina Press

- ↑ Diane M. Smith (1999), Fanny and Joshua: The Enigmatic Lives of Frances Caroline Adams and Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, Thomas Publications, ISBN 157747046X

- ↑ Col. Chamberlain & the 20th Maine Infantry, Battle of Gettysburg Virtual Tour, National Park Service

- ↑ John J. Pullen (1999), Joshua Chamberlain: a hero's life and legacy, Stackpole Books, ISBN 0811708861, pp. 15 and 112

- ↑ Joshua Lawrence Chamberlain, The passing of the armies : an account of the final campaign of the Army of the Potomac, based upon personal reminiscences of the Fifth army corps

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 19-20

- ↑ Mark Perry (1997), Conceived in Liberty: Joshua Chamberlain, William Oates, and the American Civil War, Viking, ISBN 0670862258, pp. 313-315, 317

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 17-19

- ↑ Perry, pp. 315-316

- ↑ Pullen, p. 112

- ↑ Joshua L. Chamberlain to "Dear Fanny" [Fanny Chamberlain], Augusta: Bowdoin College, November 20, 1868

- ↑ "Greetings from the College by President Barry Mills; Joshua Chamberlain Memorial Dedication", Bowdoin College News, 31 May 2003

- ↑ U.S. News & World Report (1992), Triumph without Victory: the History of the Persian Gulf War, Random House, pp. 282-283

- ↑ , CHAPTER 1: The Army Leadership Framework, Field Manual 22-100 : Military Leadership, U.S. Army

- ↑ Pullen, pp. 179-183

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Military Workgroup

- Education Workgroup

- United States Army Subgroup

- American Civil War Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Military Content

- Education Content

- History tag

- Military tag

- United States Army tag

- American Civil War tag