Video game: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Text replacement - "London" to "London, United Kingdom") |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by one other user not shown) | |||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

== Status as an art form == | == Status as an art form == | ||

As with other emerging art forms, computer and video games have had to fight to be regarded as art forms, and still aren't by many. Those who say video games are an art form point to other contemporary technology-driven art forms and say that they took time to develop into an art form and had similar ''ad hoc'' objections to their status as art form. [[Photography]] was not initially thought of as an art form; now photography exhibitions hang alongside exhibitions of paintings in art museums like [[Tate Modern]] in [[London, United Kingdom]], the [[Museum of Modern Art]] in [[New York, New York]] and the [[Centre Georges Pompidou]] in [[Paris, France]]. Similar stories can be told of [[film]], [[radio]], [[television]], | As with other emerging art forms, computer and video games have had to fight to be regarded as art forms, and still aren't by many. Those who say video games are an art form point to other contemporary technology-driven art forms and say that they took time to develop into an art form and had similar ''ad hoc'' objections to their status as art form. [[Photography]] was not initially thought of as an art form; now photography exhibitions hang alongside exhibitions of paintings in art museums like [[Tate Modern]] in [[London, United Kingdom]], the [[Museum of Modern Art]] in [[New York, New York]] and the [[Centre Georges Pompidou]] in [[Paris, France]]. Similar stories can be told of [[film]], [[radio]], [[television]], popular music, [[jazz]] music, [[animation]] and much more. | ||

There have been exhibitions of video games in a number of major galleries. Aaron Smuts' article in ''Contemporary Aesthetics'' cites three: "Hot Circuits: A Video Arcade" was an exhibition of early video arcade games at the [[American Museum of the Moving Image]] in 1989-1990; the "BitStreams" exhibition at the [[Whitney Museum of American Art]] in [[New York, New York|New York City]] in 2001; and the [[San Francisco Museum of Modern Art]]'s July 2001 symposium "ArtCade: Exploring the Relationship Between Video Games and Art".<ref name=smuts>Aaron Smuts, [http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=299 Are Video Games Art?], ''Contemporary Aesthetics'', 2005</ref> | There have been exhibitions of video games in a number of major galleries. Aaron Smuts' article in ''Contemporary Aesthetics'' cites three: "Hot Circuits: A Video Arcade" was an exhibition of early video arcade games at the [[American Museum of the Moving Image]] in 1989-1990; the "BitStreams" exhibition at the [[Whitney Museum of American Art]] in [[New York, New York|New York City]] in 2001; and the [[San Francisco Museum of Modern Art]]'s July 2001 symposium "ArtCade: Exploring the Relationship Between Video Games and Art".<ref name=smuts>Aaron Smuts, [http://www.contempaesthetics.org/newvolume/pages/article.php?articleID=299 Are Video Games Art?], ''Contemporary Aesthetics'', 2005</ref> | ||

| Line 133: | Line 133: | ||

==References== | ==References== | ||

{{reflist|2}} | {{reflist|2}} | ||

[[Category:Suggestion Bot Tag]] | |||

Latest revision as of 07:00, 5 November 2024

A video game is a game played using an electronic controller to manipulate images on a display screen. The earliest video games merit little additional description; most were abstractions, blips on a black and white screen designed to simulate sports and board games. Advances in computer technology, however, have led to exponential increases in the conceptual and visual sophistication of video games, allowing players to inhabit elaborately detailed worlds and control digital avatars with a vast array of actions and choices.

Platforms

Video games can appear on many different platforms including console video games, video games, arcade games, and hand held devices including handheld game consoles, PDAs, and cellular phones.

Video games are typically manipulated via an input device. This input device varies from platform to platform but may include a joystick, a mouse, a keyboard, pedals, a phone number pad, or a console specific controller. Video game controllers have evolved over the years, and now are even motion sensitive, and can tell when the person holding the controller is moving his or her hands in a certain manner (such as when fishing or bowling).

Gaming on the PC

Improvements in computer technology have allowed the simplistic graphics and gameplay of early, mainframe-bound computer games like Spacewar! to evolve over time, at the same time spurring consumer adoption of PCs through the 1970s and 1980s. However, the console games are now significantly more popular than those on the PC.[1]

PC games are generally created by one or more game developers, usually working in conjunction with a game publisher to distribute their work on either physical media such as CDs and DVDs, online delivery services such as Direct2Drive and Steam, or a combination of both. Once delivered and installed on the player's computer, the game may be played depending on the extent to which the computer meets its minimum system requirements, as less capable computers tend to struggle with progressively complex game engines.

PC game development

Game development, as with console games, is generally undertaken by one or more game developers using either standardised or proprietary tools. While games could previously be developed by very small groups of people, as in the early example of Wolfenstein 3D, many popular computer games today require large development teams and budgets running into the millions of dollars.[2]

PC games are usually built around a central piece of software, known as a game engine,[3] that simplifies the development process and enables developers to easily port their projects between platforms. Unlike most consoles, which generally only run major engines such as Unreal Engine 3 and RenderWare due to restrictions on homebrew software, personal computers may run games developed using a larger range of software. As such, a number of alternatives to expensive engines have become available, including open source solutions such as Crystal Space, OGRE and DarkPlaces.

User-created modifications

- Main article: Mod (computer gaming)

The multi-purpose nature of personal computers often allows users to modify the content of installed games with relative ease. Since console games are generally difficult to modify without a proprietary software development kit, and are often protected by legal[4] and physical[5] barriers against tampering and homebrew software, it is generally easier to modify the personal computer version of games using common, easy-to-obtain software. Users can then distribute their customised version of the game (commonly known as a mod) by any means they choose.

Modding had allowed much of the community to produce game elements that would not normally be provided by the developer of the game. This may unlock or introduce objectionable content, such as the famous a third party modification modification to Grand Theft Auto: San Andreas, but are generally used to expand or modify normal gameplay.

Computer gaming technology

Hardware

Virtually all personal computers use a keyboard and mouse for user input, although other common gaming peripherals are a headset and microphone for faster communication with teammates or opponents in online games, joysticks for flight simulators, and steering wheels for driving games.

Many computer games today place great emphasis on the processing power of the computer, requiring good performance from both the CPU and graphics card in order to produce smooth gameplay in increasingly complex 3D games. As a result, gaming-related hardware is frequently improved upon to meet the demands of successive generations of games.

Operating systems

At present, computer games commonly require a specific operating system such as Microsoft Windows to function. While most games are developed for Windows,[6] Mac OS X and Linux versions of more popular titles usually become available through porting houses such as Aspyr, or multi-platform developers such as Blizzard Entertainment.

Emulation

Emulation software, used to run software without the original hardware, have found some popularity for their ability to play legacy video games without the consoles or operating system for which they were designed. Console emulators, such as NESticle and MAME, have become relatively commonplace in recent years. However, the complexity of modern consoles such as the Xbox makes them far more difficult to emulate, even for the original manufacturers.[7]

Distribution

Traditional distribution

Typically, computer games are sold at retail on standard storage media, such as compact discs, DVD, and floppy disks.[8] Different formats of floppy disks were initially the staple storage media of the 1980s and early 1990s, but have fallen out of practical use as the increasing sophistication of computer games raised the overall size of the game's data and program files.

The introduction of complex graphics engines in recent times has resulted in additional storage requirements for modern games, and thus an increasing interest in CDs and DVDs as the next compact storage media for personal computer games. The rising popularity of DVD drives in modern PCs, and the larger capacity of the new media (a single-layer DVD can hold up to 4.7 gigabytes of data, more than five times as much as a single CD), have resulted in their adoption as a format for computer game distribution. To date, CD versions are still offered for most games, while some games offer both the CD and the DVD versions.

Shareware marketing, whereby a limited or demonstration version of the full game is released to prospective buyers without charge, has been used as a method of distributing computer games since the early years of the gaming industry. Shareware games generally offer only a small part of the gameplay offered in the retail product, and may be distributed with gaming magazines, in retail stores or on developers' websites free of charge.

In the early 1990s, shareware distribution was common among fledging game companies such as Apogee Software, Epic Megagames and id Software, and remains a popular distribution method among smaller game developers. However, shareware has largely fallen out of favor among established game companies in favour of traditional retail marketing, with some notable exceptions such as Big Fish Games and PopCap Games continuing to use the model today.[9]

Online delivery

With the increased popularity of the Internet, online distribution of game content has become more common.[10] Retail services such as Direct2Drive and Download.com allow users to purchase and download large games that would otherwise only be distributed on physical media, such as DVDs, as well as providing cheap distribution of shareware and demonstration games. Other services, such as GameTap, allow a subscription-based distribution model in which users pay a monthly to download and play as many games as they wish.

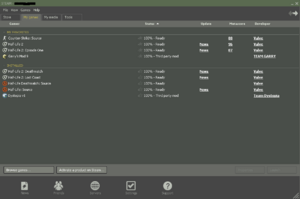

The Steam system, developed by Valve Corporation, provides an alternative to traditional online services. Instead of allowing the player to download a game and play it immediately, some games are made available for "pre-load" in an encrypted form days or weeks before their actual release date. On the official release date, a relatively small component is made available to unlock the game.

History

Early growth

The first computer game is generally considered to be Spacewar!, developed in 1961 for the PDP-1 mainframe computer by two students and an employee of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.[11] Other computer games followed in later years, such as the first text adventure game, Adventure, in 1972.[12] However, until the development of the microprocessor these games were limited to computers too large to install in the home. The release of the Intel 8080 in April 1974 and affordable computers such as the Apple II and Commodore 64 made personal computers accessible to the general public.

These cheap computers were perceived as an educational tool by many parents, especially in the United Kingdom, which produced its own home computers such as the Dragon 32 and the BBC Micro. As a result of the increasing popularity of home computers, homebrew software developers such as Phillip and Andrew Oliver soon began to create PC games of their own, while video game publishers such as Codemasters achieved initial success in distributing newly developed titles.[13]

The first video games

One of the first video games that come to mind is Pong, however this was not the first patent filed detailing what would later be described as a video game. U.S. Patent #2,455,992, titled "CATHODE-RAY TUBE AMUSEMENT DEVICE," is arguably the first video game patent ever filed in the United States.[14]

Graphical improvements

Increasing adoption of the computer mouse and high resolution bitmap displays allowed the industry to include graphical interfaces in new releases. Meanwhile, the Commodore Amiga computer achieved great success in the market from its release in 1985, contributing to the rapid adoption of these new interface technologies.[15]

The FPS genre was created with the release of id Software's Wolfenstein 3D in 1992, and remains one of the highest-selling genres today.[16] The game was originally distributed through the shareware distribution model, allowing players to try a limited part of the game for free but requiring payment to play the rest, and represented one of the first uses of texture mapping graphics in a popular game.[17]

While leading Sega and Nintendo console systems kept their CPU speed at 3-7 MHz, the 486 PC processor ran much faster at 66 MHz, allowing it to perform many more calculations per second. The 1993 release of Doom on the PC was a breakthrough in 3D graphics, and was soon ported to various game consoles in a general shift toward greater realism.[18]

Many early PC games included extras such as the peril-sensitive sunglasses that shipped with The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. These extras gradually became less common, but many games were still sold in the traditional over-sized boxes that used to hold the extra "feelies". Today, such extras are usually found only in Special Edition versions of games, such as Battlechests from Blizzard.[19]

Contemporary gaming

By 1995, the rise of Microsoft Windows and success of 3D console titles such as Super Mario 64 sparked great interest in hardware accelerated 3D graphics on the PC, and soon resulted in attempts to produce affordable solutions with the ATI Rage, Matrox Mystique and Silicon Graphics ViRGE. As 3D graphics libraries such as DirectX and OpenGL matured and knocked proprietary interfaces out of the market, these platforms gained greater acceptance in the market, particularly with their demonstrated benefits in games such as Unreal.[20] However, major changes to the Microsoft Windows operating system, by then the market leader, made many older MS-DOS-based based unplayable on Windows NT, and later, Windows XP.[21]

The faster graphics accelerators and improving CPU technology have resulted in ever-increasing levels of realism that characterise contemporary PC gaming. During this time, the improvements introduced with products such as ATI's Radeon R300 and NVidia's GeForce 6 Series have allowed game developers to increase the complexity of modern game engines. PC gaming currently tends strongly toward improvements in 3D graphics.[22]

Unlike the generally accepted push for improved graphical performance, the use of physics engines in computer games has become a matter of debate since announcement and recent release of the AGEIA PhysX PPU, ostensibly competing with middleware such as the Havok physics engine. The new technology has prompted argument over the viability of hardware accelerated physics in video games, as with accelerated graphics. In particular, the difficulty in ensuring that players' experiences are consistent with or without an installed PPU,[23] and the uncertain value of first generation PhsyX cards in games such as Ghost Recon: Advanced Warfighter[24] and City of Villains,[25] have provoked an ongoing dispute over the benefits of such emerging new technologies.

Similarly, recent years have seen many game publishers experimenting with new forms of game marketing. Chief among these new strategies is episodic gaming, an adaptation of the older concept of expansion packs, in which game content is provided in smaller quantities but for a proportionally lower price. Recent titles such as Half-Life 2: Episode One have taken advantage of the new idea, with mixed results rising from concerns for the amount of content provided for the price.[26]

Gaming genres

- See also: Video game genres

Personal computers have at times been superior to their equivalent video game consoles, and thus capable of playing more graphically sophisticated games and prompting the rise of entire genres such as the first person shooter. However, the two platforms have largely converged in processing power with upcoming seventh generation video game consoles such as the Playstation 3, and the 2005 release of the Xbox 360.

The real time strategy genre has found very little success outside of personal computers, with releases such as Starcraft 64 failing in the marketplace due difficulties in playing the game using the Nintendo 64 controller, and other changes from the original version.[27] Specifically, console joysticks and gamepads are able to reproduce neither the quick, accurate movements of a mouse, nor the wide range of simultaneous input options of a keyboard. Notable exceptions include The Lord of the Rings: The Battle for Middle-earth II, released for the Xbox 360 in a modified form in 2006.

Conversely, genres such as racing games have found considerable success with the analog joysticks found on modern console controllers, since these allow for sustained motion and smoother control than either a mouse or keyboard or joystick.

Status as an art form

As with other emerging art forms, computer and video games have had to fight to be regarded as art forms, and still aren't by many. Those who say video games are an art form point to other contemporary technology-driven art forms and say that they took time to develop into an art form and had similar ad hoc objections to their status as art form. Photography was not initially thought of as an art form; now photography exhibitions hang alongside exhibitions of paintings in art museums like Tate Modern in London, United Kingdom, the Museum of Modern Art in New York, New York and the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris, France. Similar stories can be told of film, radio, television, popular music, jazz music, animation and much more.

There have been exhibitions of video games in a number of major galleries. Aaron Smuts' article in Contemporary Aesthetics cites three: "Hot Circuits: A Video Arcade" was an exhibition of early video arcade games at the American Museum of the Moving Image in 1989-1990; the "BitStreams" exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City in 2001; and the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art's July 2001 symposium "ArtCade: Exploring the Relationship Between Video Games and Art".[28]

In 2002, the Barbican Art Gallery in London organised the Game On exhibition which showed the history of video games: from early arcade games and computer games through to highly sophisticated modern console and PC games. This exhibition has toured around the world.[29] The Manchester Urbis Centre displayed an exhibition called "videogame nation" in 2009.[30][31]

The American movie critic Roger Ebert has argued that no videogames yet reach the status of art.[32]

Controversy

Computer and video games have long been a source of controversy, particularly related to the violence that has become commonly associated with video gaming in general. The debate surrounds the influence of objectionable content on the social development of minors, with organisations such as the American Psychological Association concluding that video game violence increases children's aggression,[33] a concern that prompted a further investigation by the Centers for Disease Control in September 2006.[34] Industry groups have responded by noting the responsibility of parents in governing their children's activities, while attempts in the United States to control the sale of objectionable games have generally been found unconstitutional.[35]

Video games, as they have risen in popularity, have come under criticism by parents groups, religious groups, politicians, and other groups for in-game depictions of crime, violence, drug use, sex, profanity and other activities and topics typically looked upon negatively in public perception. Some critics of video games claim that playing video games can negatively influence children's behavior and even influence children to commit crimes in mimicry of actions that they see in-game. Proponents of video games argue that this is not the case, and some claim that video games are in fact beneficial to child development. Some say that video games may play a large role in decreasing violence, through sublimation.

Game addiction has become a major source of criticism for both PC games and console games alike, focusing on the potential for minors to be affected by violence and other objectionable content. Such criticism has prompted attempts to regulate the sale of certain video games to minors in various countries, although they have been unsuccessful in the United States.[35] Video game addiction can have a negative influence on health and on social relations, and has lead to deaths as a result of extremely prolonged gameplay.[36] The problem of addiction and its health risks seems to have grown with the recent rise of massively multiplayer online role-playing games (MMORPGs).[37]

See also

References

- ↑ Entertainment Software Association (January 26, 2005). Computer and Video Game Software Sales Reach Record $7.3 Billion in 2004. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Wardell, Brad (2006-04-05). [http://www.gamasutra.com/features/20060405/wardell_01.shtml Postmortem: Stardock's Galactic Civilizations II: Dread Lords]. Retrieved on 2006-09-13.

- ↑ Simpson, Jake. Game Engine Anatomy 101, Part I. Retrieved on 2006-09-22.

- ↑ Judge deems PS2 mod chips illegal in UK (July 2004). Retrieved on 2006-09-22.

- ↑ Xbox 360 designed to be unhackable (October 2005). Retrieved on 2006-09-22.

- ↑ Xbox 360 Review (November 2005). Retrieved on 2006-09-12.

- ↑ The Next Billion Dollar Videogame Opportunity. Retrieved on 2006-09-24.

- ↑ Chris Morris. The return of shareware, CNN.com, June 18, 2003. Retrieved on 2006-09-24.

- ↑ Brendan Sinclair (June 18, 2003). Spot On: The (new) dawn of digital distribution. Retrieved on 2006-09-23.

- ↑ Levy, Steven (1984). Hackers: Heroes of the Computer Revolution. Anchor Press/Doubleday. ISBN 0385191952.

- ↑ Chronology of the History of Video Games. Retrieved on 2006-09-23.

- ↑ Discovery Channel. History of Video Games [TV-Series].

- ↑ "Jed Margolin's Video Game Patents" (08-April-2007).

- ↑ Commodore Amiga 1000 Computer. Retrieved on 2006-08-16.

- ↑ Cifaldi, Frank (2006-02-21). Analysts: FPS 'Most Attractive' Genre for Publishers. Retrieved on 2006-08-17.

- ↑ James, Wagner. Masters of "Doom". Retrieved on 2006-09-23.

- ↑ Console history. Retrieved on 2006-09-23.

- ↑ Varney, Allen. Feelies. Retrieved on 2006-09-24.

- ↑ Shamma, Tahsin. Review of Unreal, Gamespot.com, June 10, 1998.

- ↑ Durham, Jr., Joel (2006-05-14). Getting Older Games to Run on Windows XP. Retrieved on 2006-09-22.

- ↑ Necasek, Michal (2006-10-30). Brief Glimpse into the Future of 3D Game Graphics. Retrieved on 2006-09-23.

- ↑ Reimer, Jeremy (2006-05-14). Tim Sweeney ponders the future of physics cards. Retrieved on 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Shrout, Ryan (2006-05-02). AGEIA PhysX PPU Videos - Ghost Recon and Cell Factor. Retrieved on 2006-08-22.

- ↑ Smith, Ryan (2006-09-07). PhysX Performance Update: City of Villains. Retrieved on 2006-09-13.

- ↑ Half Life 2: Episode One for PC Review (June 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-02.

- ↑ Joe Fielder (2000-05-12). StarCraft 64. Gamespot.com. Retrieved on 2006-08-19.

- ↑ Aaron Smuts, Are Video Games Art?, Contemporary Aesthetics, 2005

- ↑ Barbican.org.uk - Game On - Tour

- ↑ videogame nation at Manchester Urbis.

- ↑ Review at NegativeGamer.com of videogame nation

- ↑ Roger Ebert, Video games can never be art, Chicago Sun-Times

- ↑ American Psychological Association. Violent Video Games - Psychologists Help Protect Children from Harmful Effects.

- ↑ Senate bill mandates CDC investigation into video game violence (September 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-19.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Judge rules against Louisiana video game law (August 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-02.

- ↑ S Korean dies after games session (August 2005). Retrieved on 2006-09-21.

- ↑ Detox For Video Game Addiction? (July 2006). Retrieved on 2006-09-12.