Schizophrenia

Schizophrenia1 is a mental disorder characterized by patterns of disordered thought, language, motor, and social function. [1] Males typically develop symptoms in their late teens and early 20s, while females exhibit a later onset, usually in the mid-20s to early 30s. More variations in onset and symptomology may exist across gender, age, and culture, although these factors have not been clearly deliniated.

During the acute stage of schizophrenia, the primary symptom is a break from reality in which individuals experience thoughts, perceptions and beliefs that are considered strange and bizarre by the general population. Despite common and popular perception, the multiple personalities and dissociative characteristics associated with dissociative identity disorder are in no way related to schizophrenia, and the two are completely separate disorders. The specific cause of schizophrenia is largely unknown, although several neurotransmitters and brain structures are hypothesized to play a role in the disorder.

History

Descriptions of schizophrenia reach back into ancient times, although the word schizophrenia has only been recently used. In 1887, German psychiatrist Emil Kraepelin described the symptoms of schziophrenia as the single disorder dementia praecox. Even at that time, he showed considerable foresight by advancing the notion that the disorder was caused by organic pathology, which he predicted was damage or death of cells in the cerebral cortex. This prediction is supported as part of the cause, while more structural abnormalities are considered in the causes section. He was not, however, the first person to describe or classify schizophrenic behaviour, but he was the first to unify it into a broad, overarching colllection of signs and symptoms. Earlier in 1871, Ewald Hecker, another German psychiatrist, described hebephrenia, a classification that continues to this day as the disorganized schizophrenia subtype.[2] The 10th edition of the World Health Organization's International Classification of Disease continues with a hebephrenic schizophrenia subtype. Schizophrenia has existed as a diagnostic category in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual since the first edition, although its description and presumed causes have changed over the years. The diagostic criteria is more narrow since the creation of similar and related disorders such as schizotypal personality disorder.

The word schizophrenia was introduced in 1908 by psychologist Eugen Bleuler in his work Dementia Praecox oder Gruppe der Schizophrenien (Dementia Praecox or the Group of Schizophrenias). He used the word schizophrenia to emphasize the split (schiz) of mental processes within the mind.

Diagnosis and classification

Note: The American Psychiatric Association, which publishes the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, forbids the unauthorized reproduction of their diagnostic criteria. A narrative of the DSM-IV-TR criteria follows.

For a person to be diagnosed with schizophrenia, a person must display two or more of the following symptoms for a significant portion of one month, and they must cause a significant level of disturbance in one's life: delusions, hallucinations (usually auditory as visual are rare), disorganized speech, disorganized or catatonic behavior, or negative symptoms. (These symptoms are classified as Criterion A in the DSM).

Some signs must be present for at least six months since the onset of the disturbances, with at least one month of symptoms that meet the criterion A symptoms. However, only one of these symptoms is required if the delusions are bizarre, the patient hallucinates an auditory commentary of their actions or hears two or more voices participating in conversation with each other. The symptoms of these periods may manifest as only negative symptoms, or by two or more of the criterion A symptoms.

As with any disorder, there are several criteria that exclude a diagnosis. A patient will not receive a diagnosis of schizophrenia if they are schizoaffective or have a mood disorder with psychotic features, as no mood disorders occur at the same time as active phase symptoms, or have a brief duration compared to the active and residual phases. Substance use and medical conditions can mimic schizophrenia, and so a diagnosis will not be made if symptoms are due to their direct effects. A history of autism or another pervasive developmental disorder will exclude a diagnosis of schizophrenia unless prominent delusions or hallucinations are present for more than a month.

Subtypes

There are several general patterns of schizophrenia. These subtypes have been identified to aid research, treatment, and communication among mental health care providers and patients. In a clinical presentation, each pattern is rarely as distinct and clear-cut as is presented below.

Disorganized schizophrenia is characterized by prominently disorganized speech and behavior, with flat or inappropriate affect (display of emotion). This subtype is the closest to the stereotype of a "crazy person". A patient will not receive this classification if they meet the criteria for the catatonic type. Catatonic schizophrenia is characterized by at least two of the following symptoms: catalepsy (a lack of voluntary movement), excessive and purposeless motor activity (uninfluenced by external stimuli), very strong negativism (maintaining a rigid position and resisting all attempts to be moved) or mutism, peculiar voluntary movement and posturing (often taking bizarre or inappropriate positions), stereotyped movements, with conspicuous mannerisms or grimacing, or echolalia or echopraxis (immediate repetition of someone's words or actions). Paranoid schizophrenia is characterized by delusions or hallucinations of a relatively consistent nature, usually related to themes of persecution or grandeur. Positive symptoms are most prominent as the patient retains largely coherent speech, a fairly normal display of emotions behavior. The prognosis is favorable, as it responds well to antipsychotic medication. Undifferentiated schizophrenia occurs when the symptoms meet criterion A, and the patient does not fit into the paranoid, disorganized, or catatonic subtypes. Residual schizophrenia has the absence of prominent delusions and hallucinations, disorganized speech or catatonic behaviour. However, there is a continued disturbance as marked by having two or more criterion A symptoms, but present in a weakened form. These symptoms could take the form of odd beliefs, or unusual (but not psychotic) perceptual experiences.

Dimensions

Another way of classifying schizophrenic behaviors is by identifying symptoms that exist on a continuum with varying degrees of severity rather than discrete groups. The positive-negative dimension comprises positive symptoms, meaning the presence of something normally absent, characterized by prominent delusions, hallucinations, positive formal thought disorder, and persistently bizarre behavior. Negative symptoms are the absence of something that is normall present, such as flattened or masked affect, alogia, avolition, anhedonia, and attentional impairment.[3] The Positive and Negative Syndrome Scale (PANSS) is a 30-item psychiatric rating scale that can gauge the relationship of positive and negative symptoms, their differential, and the severity of illness.[4] The paranoid-nonparanoid dimension is the presence or absence of delusion of persecution or grandeur. This dimension may be related to the process-reactive dimension.[5] The process-reactive, or good-poor premorbid dimension attempts to classify the variation in acute symptom onset. Some individuals experience a prolonged prodromal phase, while others go from normal functioning to full-blown psychosis within days. Cases with a gradual onset are called process, while sudden onset precipitated by a traumatic or stressful event is called reactive. A more continuous dimension is the good-poor dimension that describes how well the patient functioned before the active phase onset. These adjustment are useful in predicting prognosis as individuals with poor-premorbid schizophrenia are more likely to have long hospitalizations, and more likely to require re-hospitalization compared with good-premorbid patients.[6]

Some researchers have hypothesized two classifications of schizophrenia, known as Type I and Type II. Type I schizophrenia is reactive, has positive symptoms, and a good level of premorbid functioning. Treatment outcomes are generally good as this type will respond favourably to antipsychotic medication. These symptoms are thought to be due to chemical abnormalities as abnormal brain structures are absent. Type II schizophrenia is process, characterized by negative symptoms, and a poor level of premorbid functioning. Response to medication tends to be poor as abnormal brain structures may be present.

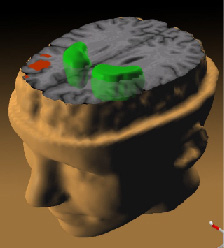

Brain morphometry

Another way of diagnosing schizophrenia and classifying its subtypes is by means of neuroimaging. Initial steps in this direction have been undertaken using pneumoencephalography, a harsh procedure focused on detecting the enlarged ventricles typically found in schizophrenic patients. More recently, in the wake of considerable advances in neuroimaging technology, analyses of such morphological abnormalities have shifted from the qualitative to the quantitative side [7], giving rise to brain morphometry as the field concerned with statistical analyses of structural changes in neuroimaging data, as compared to healthy subjects matched in gender, ethnicity and age[8]. Morphometric abnormalities related to schizophrenia have been observed in various brain regions, affecting cortical and subcortical regions, gray and white matter[9][10]. Typical findings include reduced cortical thickness and gyrification, particularly in frontal and temporal areas of the cortex, as well as grey matter reductions in subcortical structures like the hippocampus [11]. However, some studies also found grey matter volume increases for some populations of schizophrenics or high-risk groups for developing schizophrenia.[12]

Course of illness

Individuals differ in symptom intensity and presentation over time. Schizophrenia is considered a chronic, relapsing disorder since patients will experience residual symptoms after an active period, and cycle between the two.

Prodromal

The prodromal phase is a gradual deterioration of functioning, marked by strange behavior and social isolation. This occurs before any clear psychotic symptoms appear, and may last for years or days before developing into full blown, active schizophrenia. It can be difficult to differentiate the symptoms of the prodromal phase from the symptoms of another mental disorder or just being a teenager. The symptoms can include social withdrawal, decreased concentration, attention, depressed mood, sleep disturbance, anxiety, suspiciousness, absenteeism and irritability.

Early detection of prodromes has been controversial, as early interventions may or may not reduce the length of active psychosis, or improve later treatment outcomes.

Active

The active phase is marked by prominent psychotic symptoms. The signs and symptoms that occur during this phase are outlined in the diagnosis section.

Residual

The residual phase occurs after an active period of psychosis has finished. Individuals will continue to experiences cognitive, behavioral, and social dysfunctions but not as strongly as during an active episode. The risk of relapse into psychosis is a continual concern.

Epidemiology

The incidence of schizophrenia varies with a median of 15.2 per 100,000, with males more likely than females to develop schizophrenia at a ratio of 1.4 to 1. Individuals who immigrate have a median risk ratio of 4.6 compared to individuals born in that country. Individuals living in urban areas have a higher risk than those in mixed urban/rural sites.[13] The prevalence of schizophrenia does not significantly differ between males and females, or between urban, rural, and mixed sites. Migrants have a higher prevalence of schizophrenia compared to native-born individuals with a 1.8:1 ratio. Economically, prevalence estimates in emerging and developed countries are higher than in less developed countries.[14] Schizophrenia is more prevalent among the homeless than in the general population, as mental illness is both a risk factor for becoming homeless, and the stress of being homeless can trigger or worsen a mental illness. One systematic review found an average of 11% of homeless individuals have schizophrenia.[15]

Rates of suicide are higher among schizophrenics than the general population, with about 10% completing suicide while up to half are estimated to attempt suicide at least once in their lifetime.[16]

Protective and risk factors

Cannabis use is a risk factor for psychosis and developing psychotic symptoms.[17]

A high level of emotion displayed by family members of an individual with schizophrenia, called expressed emotion, significantly predicts relapse into the active phase.[18]

As with many mental illnesses, a strong social network allows patients to better cope with the disease.

Causes

The exact cause of schizophrenia is unknown, but several biochemical and structural abnormalities have been found and remain the focus for research and treatment. Antipsychotic medication may produce cognitive deficits, so researchers are challenged to differentiate between the illness and drug side-effects, as well as co-morbid mental disorders and illicit drug use.

The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia, that is, schizophrenia may be due to a dopaminergic dysregulation, is based on several lines of evidence. First, individuals with Parkinson's disease are treated with dopamine precursors, most commonly L-dopa, which allow the brain to synthesize additional dopamine. Some patients begin to display similar to schizophrenia as a side-effect to the drug, which presumably produce abnormally high levels of dopamine. Also, antipsychotic drugs can produce Parkinsonian side effects by lowering dopamine function. Secondly, amphetamines can induce temporary psychosis and behaviors similar to schizophrenia in otherwise healthy individuals, and it also worsens symptom severity in patients with schizophrenia. A serendipitous discovery occurred in the 1950s when physicians found that chlorpromazine, a drug used previously for a different purpose, reduced the positive symptoms of schizophrenia. Chlorpromazine is a member of the phenothiazine class of drugs used to treat schizophrenia, and exerts its action by blocking dopamine receptors, thus reducing the effects of dopamine. This evidence may reflect abnormalities not with dopamine itself, but rather with the systems with which it interacts: the the fronto-striato-pallido-thalamic loops, and the limbic structures, such as amygdala and hippocampus.[19]

A second biochemical area of research concerns the neurotransmitter glutamate and NMDA receptors. Postmortem examinations have found abnormally low levels of NMDA recpetors, and dysfunctions within subunits. This suggest an impairment of glutamate binding both within and projecting out from the hippocampus.[20] Drugs that block NMDA receptors, such as ketamine, mimic the negative symptoms of schizophrenia and provide further evidence of glutamate dysfunction.[21]

The most commonly found structural abnormalities in schizophrenic patients are enlarged lateral and third ventricles, as well as decreased brain matter. Most affected is the temporal lobe which often shows a reduction in volume.[22] Positron emission topography studies have found a loss of grey matter in subcorticol structures. Other neuro-imaging studies have found decreased neuron activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, which may explain the cognitive deficits in attention and planning not caused by antipsychotic treatment.[23]

Treatment

The first line treatment for schizophrenia is antipsychotic medication, while cognitive and behavioral therapy have also been shown to be beneficial.

Antipsychotic drugs are used to reduce the symptoms of psychosis. Their primary mechanism of action is through regulating the activity dopamine, a neurotransmitter considered in the causes section. These medications are classified into typical and atypical antipsychotics based on loosely defined criteria such as pharmacological action or perceived side-effects. Atypical antipsychotics are considered to be superior in efficacy compared to typical antipsychotics when treating schizophrenia, although a 2000 systematic overview and meta-regression analysis published by the British Medical Journal found typical and atypical antipsychotics to have a similar effect on symptoms. However, atypicals were found to cause fewer extrapyramidal side effects.[24]

Many individuals with schizophrenia smoke cigarettes, estimated at two to four times the prevalence of the normal population. This may be an attempt to self-medicate. Nicotine increases cholinergic transmission and improves attention and working memory.[25] Some components of tobacco also behave as monoamine oxidase inhibitors.[26] By raising monoamine levels, tobacco would reduce negative symptoms, like selegiline, another MAOI that has been proposed as an add-on therapy to cope with the negative symptoms in schizophrenia.[27][28]

Notes

1From the Greek, schiz - to split, and phren - mind

References

- ↑ American Psychiatric Association. (2000). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. American Psychiatric Press: Washington DC

- ↑ Kruger S, Braunig P (2000). "Ewald Hecker, 1843-1909". Am J Psychiatry 157 (8): 1220. PMID 10910782. [e]

- ↑ Andreasen NC, Olsen S (1982). "Negative v positive schizophrenia. Definition and validation". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 39 (7): 789–94. PMID 7165478. [e]

- ↑ Kay SR, Fiszbein A, Opler LA (1987). "The positive and negative syndrome scale (PANSS) for schizophrenia". Schizophr Bull 13 (2): 261–76. PMID 3616518. [e]

- ↑ Fenton WS, McGlashan TH (1991). "Natural history of schizophrenia subtypes. I. Longitudinal study of paranoid, hebephrenic, and undifferentiated schizophrenia". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 48 (11): 969–77. PMID 1747020. [e]

- ↑ Robinson D, Woerner MG, Alvir JM, et al (1999). "Predictors of relapse following response from a first episode of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 56 (3): 241–7. PMID 10078501. [e]

- ↑ Gur RE, Keshavan MS, Lawrie SM (2007). "Deconstructing psychosis with human brain imaging". Schizophr Bull 33 (4): 921-31. DOI:10.1093/schbul/sbm045. PMID 17548845. PMC PMC2632317. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Shenton, M.E.; C.C. Dickey & M. Frumin et al. (2001), "A review of MRI findings in schizophrenia", Schizophrenia Research 49 (1-2): 1–52, DOI:10.1016/S0920-9964(01)00163-3

- ↑ Ananth, Hema; Ioana Popescu & Hugo D. Critchley et al. (2002), "Cortical and Subcortical Gray Matter Abnormalities in Schizophrenia Determined Through Structural Magnetic resonance imaging with Optimized Volumetric Voxel-Based Morphometry", American Journal of Psychiatry 159 (9): 1497–505, DOI:10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1497

- ↑ Davatzikos, Christos; Dinggang Shen & Ruben C. Gur et al. (2005), "Whole-Brain Morphometric Study of Schizophrenia Revealing a Spatially Complex Set of Focal Abnormalities", Archives of General Psychiatry 62 (11): 1218–27, DOI:10.1001/archpsyc.62.11.1218

- ↑ Kulynych, J.J.; L.F. Luevano & D.W. Jones et al. (1997), "Cortical abnormality in schizophrenia: an in vivo application of the gyrification index", Biological Psychiatry 41 (10): 995–999, DOI:10.1016/S0006-3223(96)00292-2

- ↑ Phillips LJ, Velakoulis D, Pantelis C, Wood S, Yuen HP, Yung AR et al. (2002). "Non-reduction in hippocampal volume is associated with higher risk of psychosis". Schizophr Res 58 (2-3): 145-58. PMID 12409154.

- ↑ McGrath J, Saha S, Welham J, El Saadi O, MacCauley C, Chant D (2004). "A systematic review of the incidence of schizophrenia: the distribution of rates and the influence of sex, urbanicity, migrant status and methodology". BMC Med 2: 13. DOI:10.1186/1741-7015-2-13. PMID 15115547. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Saha S, Chant D, Welham J, McGrath J (2005). "A systematic review of the prevalence of schizophrenia". PLoS Med. 2 (5): e141. DOI:10.1371/journal.pmed.0020141. PMID 15916472. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Folsom D, Jeste DV (2002). "Schizophrenia in homeless persons: a systematic review of the literature". Acta Psychiatr Scand 105 (6): 404–13. PMID 12059843. [e]

- ↑ Siris SG (2001). "Suicide and schizophrenia". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 15 (2): 127–35. PMID 11448086. [e]

- ↑ Semple DM, McIntosh AM, Lawrie SM (2005). "Cannabis as a risk factor for psychosis: systematic review". J. Psychopharmacol. (Oxford) 19 (2): 187–94. PMID 15871146. [e]

- ↑ Bebbington P, Kuipers L (1994). "The predictive utility of expressed emotion in schizophrenia: an aggregate analysis". Psychol Med 24 (3): 707–18. PMID 7991753. [e]

- ↑ Willner P (1997). "The dopamine hypothesis of schizophrenia: current status, future prospects". Int Clin Psychopharmacol 12 (6): 297–308. PMID 9547131. [e]

- ↑ Gao XM, Sakai K, Roberts RC, Conley RR, Dean B, Tamminga CA (2000). "Ionotropic glutamate receptors and expression of N-methyl-D-aspartate receptor subunits in subregions of human hippocampus: effects of schizophrenia". Am J Psychiatry 157 (7): 1141–9. PMID 10873924. [e]

- ↑ Lahti AC, Weiler MA, Tamara Michaelidis BA, Parwani A, Tamminga CA. (2001). Effects of ketamine in normal and schizophrenic volunteers. Neuropsychopharmacology, 25(4), 455–67. PMID 11557159

- ↑ McCarley RW, Wible CG, Frumin M, et al (1999). "MRI anatomy of schizophrenia". Biol. Psychiatry 45 (9): 1099–119. PMID 10331102. [e]

- ↑ Berman KF, Zec RF, Weinberger DR (1986). "Physiologic dysfunction of dorsolateral prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia. II. Role of neuroleptic treatment, attention, and mental effort". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry 43 (2): 126–35. PMID 2868701. [e]

- ↑ Geddes J, Freemantle N, Harrison P, Bebbington P (2000). "Atypical antipsychotics in the treatment of schizophrenia: systematic overview and meta-regression analysis". BMJ 321 (7273): 1371–6. PMID 11099280. [e]

- ↑ Kumari V, Postma P (2005). "Nicotine use in schizophrenia: the self medication hypotheses". Neurosci Biobehav Rev 29: 1021–34. DOI:10.1016/j.neubiorev.2005.02.006. PMID 15964073. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Talhout R et al. (2007). "Role of acetaldehyde in tobacco smoke addiction". Eur Neuropsychopharmacol 17: 627–36. DOI:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2007.02.013. PMID 17382522. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Simpson GM, Shih JC, Chen K, Flowers C, Kumazawa T, Spring B (1999). "Schizophrenia, monoamine oxidase activity, and cigarette smoking". Neuropsychopharmacology 20 (4): 392–4. DOI:10.1016/S0893-133X(98)00119-5. PMID 10088141. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Amiri A et al (2007). "Efficacy of selegiline add on therapy to risperidone in the treatment of the negative symptoms of schizophrenia: a double-blind randomized placebo-controlled study". Hum Psychopharmacol. DOI:10.1002/hup.902. PMID 17972359. Research Blogging.