Monocled cobra

| Monocled cobra | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Monocled cobra

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Naja kaouthia Lesson, 1831[2][3] | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Synonyms | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

The Monocled cobra (Naja kaouthia), also commonly referred to as the Monocellate cobra or Thai cobra is a species of venomous cobra that belongs to the family Elapidae. It is a medium sized snake that is very common throughout Southeast Asia and the eastern regions of South Asia. This species causes more human fatalities than any other snake in Thailand.

Etymology and taxonomic history

The Monocled cobra was first described by French surgeon, naturalist, ornithologist and herpetologist René Primevère Lesson in 1831.[4] The generic name Naja is a Latinisation of the Sanskrit word nāgá (नाग) meaning "cobra". The specific epithet kaouthia is derived from the Bengali term "keauthia" which means "monocle".

Since it was first described by Lesson in 1831 several monocled cobras were described under different scientific names:

- In 1834, John Edward Gray published Thomas Hardwicke’s first illustration of a monocled cobra under the trinomial Naja tripudians var. fasciata.[5]

- In 1839, Thomas Cantor described a brownish monocled cobra with numerous faint yellow transverse stripes and a hood marked with a white ring under the binomial Naja larvata, found in Bombay, Calcutta and Assam.[6]

Several varieties of monocled cobras were described under the binomial Naja tripudians between 1895 and 1913.

- Naja tripudians var. scopinucha 1895

- Naja tripudians var. unicolor 1876

- Naja tripudians var. viridis 1913

- Naja tripudians var. sagittifera 1913

In 1940, Malcolm Arthur Smith classified the monocled cobra as a subspecies of the Indian cobra under the trinomial Naja naja kaouthia.[7]

- Naja kaouthia kaouthia – Deraniyagala, 1960

Description

The monocled cobra is medium to large in length, heavy bodied snake with long cervical ribs capable of expansion to form a hood when threatened. The body of this species is compressed dorsoventrally and sub-cylindrical posteriorly. Its head is elliptical, depressed, slightly distinct from the neck with a short, rounded snout and large nostrils. The eyes are medium in size with round pupils. Dorsal scales are smooth and strongly oblique. Most adults average between 1.1 m (3.61 ft) and 1.5 m (4.92 ft) in length but they can grow to a maximum length of 2.3 m (7.55 ft).[8][9] The colour pattern on the monocled cobra is highly variable. The ground colour is generally some shade of medium to dark brown or grey-brown, or blackish. Many specimens are uniform, others show some banding. The type of pattern varies geographically. Specimens may have a dorsal surface that may be yellow, brown, gray, or blackish, with or without ragged or clearly defined cross bands. It can be olivaceous or brownish to black above with or without a yellow or orange-colored, O-shaped mark on the hood. It has a black spot on the lower surface of the hood on either side, and one or two black cross-bars on the belly behind it. The rest of the belly is usually of the same color as the back, but paler. As age advances, it becomes paler, when the adult is brownish or olivaceous. The elongated nuchal ribs enable a cobra to expand the anterior of the neck into a "hood". A pair of fixed anterior fangs is present. The largest fang recorded measured 6.78 mm (0.678 cm). Fangs are moderately adapted for spitting. The monocled cobra has an O-shaped, or monocellate hood pattern. The hood mark of this species consists of light circle with a dark centre, but may sometimes be mask-shaped, with further dark spots in the light fields of the circle. In some specimens, the hood mark is connected to the light throat area. Occasionally, the hood mark may be "scrambled", making it impossible to assign it to one of the "standard" hood mark shapes, but this is rare in India.[10][11]

The ventral colouration is variable in this species. Most specimens have a clearly defined dark band behind the light throat, followed by a mottled light area, which becomes darker posteriorly until the entire ventral surface is dark. The underside of the tail is usually light, but often suffused with dark pigment.[11]

Scalation

They have 25 to 31 scales on the neck, 19 to 21, usually 21, on the body, and 17 or 15 on the front of the vent. They have 164 to 197 ventral scales and 43 to 58 subcaudal scales.[8]

Distribution and habitat

Geographical distribution

Northern and eastern India (Gangetic Plain, Bengal, Orissa, Sikkim, Assam; most westerly record is Sonipat, Haryana; most southerly record from Orissa). It is also found in Bangladesh, Myanmar (Burma), southern China (Sichuan, Guanxi, Yunnan), Thailand (absent or rare in north and northeast, common elsewhere), northern Malaysia, Cambodia and Vietnam, north to at least Hue; recent records from northern Vietnam require confirmation, as confusion with the superficially similar Naja atra is possible. It also likely occurs in southern Laos, Bhutan, and southern Nepal. A previous report of Naja naja kaouthia from Nepal was in fact based on misidentified specimens of Naja naja.[11]

Habitat

This species can adapt to a range of habitats, including both natural and anthropogenically-modified environments. It prefers habitats associated with water, such as paddy fields, swamps, and mangroves, but can also be found in grasslands, jungle, open fields, shrublands, and forests. It also occurs in agricultural land and human settlements, including cities. It occurs up to 1000 m (3280.84 ft) above sea level, although it is usually found below elevations of 700 m (2296.59 ft).[1][12]

Behaviour and ecology

This is a terrestrial and nocturnal species, but are also found basking during daytime.[11] Often found in tree holes and areas where rodents are plentiful. It tends to head for cover if disturbed. Monocled cobras are non-spitting.[12] However, when threatened, they will raise the anterior portions of their bodies, spread their hood, usually hiss loudly, and strike in an attempt to bite and defend themselves.[9] In rice-growing areas they live in rodent burrows in the dykes between the fields and have become semi-aquatic in some areas. Juveniles take mostly amphibians. Adults eat small mammals, frogs, toads, and occasionally snakes and fish.[11]

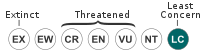

Conservation status

Naja kaouthia has been assessed as Least Concern owing to its large distribution, tolerance of a broad range of modified habitats, and its reported abundance. No major threats have been reported although it is extensively used for food, snake wine, skin trade and medicinal purposes, and has undergone at least localized population declines in the eastern part of its range. For this reason it is listed in appendix II of CITES. However, it is not known whether it is undergoing a significant population decline and more research is needed to establish whether this species might warrant reassessment. The species is probably threatened in China, Myanmar and much of Indochina, as a result of heavy exploitation for use in traditional medicine, including snake wine in Vietnam, and for skins and food. CITES data indicates, however, that it is unclear whether these pressures are sufficient to threaten the survival of subpopulations.[1]

Reproduction

This is an oviparous species. Females lay between 16 and 33 eggs per clutch. Incubation periods range from 55 to 73 days.[13] Egg-laying takes place in January to March. The females usually stay with the eggs. Some collaboration between males and females has been reported in Naja naja x Naja kaouthia - hybrids.[11]

Venom

The median lethal dose is 0.28-0.33 mg/gram of mouse body weight.[9] The major toxic components in cobra venoms are postsynaptic neurotoxins, which block the nerve transmission by binding specifically to the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor, leading to flaccid paralysis and even death by respiratory failure. The major α-neurotoxin in Naja kaouthia venom is a long neurotoxin, α-cobratoxin; the minor α-neurotoxin is different from cobrotoxin in one residue.[14] The neurotoxins of this particular species are weak.[15] The venom of this species also contains myotoxins and cardiotoxins.[16][17]

In case of intravenous injection the LD50 tested in mice is 0.373 mg/kg, and 0.225 mg/kg in case of intraperitoneal injection.[18] The average venom yield per bite is approximately 263 mg (dry weight).[19]

The monocled cobra causes the highest fatality due to snake venom poisoning in Thailand.[20] Envenomation usually presents predominately with extensive local necrosis and systemic manifestations to a lesser degree. Drowsiness, neurological and neuromuscular symptoms will usually manifest earliest; hypotension, flushing of the face, warm skin, and pain around bite site typically manifest within one to four hours following the bite; paralysis, ventilatory failure or death could ensue rapidly, possibly as early as 60 minutes in very severe cases of envenomation. However, the presence of fang marks does not always imply that envenomation actually occurred.[21]

In Myanmar (Burma), Maung TM, a 20-year old male was admitted to Insein hospital (near Yangon), within one hour of being bitten by a monocled cobra on the inner side of thigh. In fact he was bitten while squatting to urinate in the field. On admission there was a black patch and gross swelling at the site of the bite. Polyvalent serum, containing anti-viper and anti-cobra, was given intravenously on admission. On the next day the eye lids drooped and he developed signs of respiratory paralysis which demanded immediate tracheostomy and mechanical ventilation. He was again given antivenom with atropine and prostigmine with good response. The drugs were repeated as their actions had been only short lasting. The development of respiratory paralysis after an apparent recovery may indicate that there was a depot of venom at the site of bite from which it was absorbed slowly. This assumption may call for local infiltration. Locally there was extensive necrosis and ulceration requiring skin grafting at a later date.[22]

Cited references

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 1.2 Monocled cobra status at The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed 22 June 2012.

- ↑ Naja kaouthia (TSN 700628) at Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Accessed 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Naja kaouthia LESSON, 1831 at The Reptile Database. Accessed 15 June 2012.

- ↑ Lesson, R.P. 1831. Catalogue des Reptiles qui font partie d'une Collection zoologique recueille dans l'Inde continentale ou en Afrique, et apportée en France par M. Lamare-Piquot. Bulletin des Sciences Naturelles et de Géologie, Paris. 25 (2): 119-123

- ↑ Gray, J. E. (ed.) (1834) Cobra Capella. Illustrations of Indian zoology chiefly selected from the collection of Maj.-Gen. Hardwicke. Vol. II: Plate 78.

- ↑ Cantor, T. (1839) Naja larvata. Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Vol. VII: 32–33.

- ↑ Smith, M. A. (1940) Naja naja kaouthia. Records of the Indian Museum. Volume XLII: 485.

- ↑ Jump up to: 8.0 8.1 Smith, M. A. (1943). Naja naja kaouthia In: The Fauna of British India, Ceylon and Burma, Including the Whole of the Indo-Chinese Sub-Region. Reptilia and Amphibia. Volume III (Serpentes). Taylor and Francis, London. Pages 428–432.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Chanhome, L., Cox, M. J., Vasaruchaponga, T., Chaiyabutra, N. Sitprija, V. (2011). Characterization of venomous snakes of Thailand. Asian Biomedicine 5 (3): 311–328.

- ↑ Whitaker, R. (1978). Common Indian Snakes. A Field Guide. Macmillan, New Delhi. XIV + 154 pp. ISBN 1403929556.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 Wüster. Wolfgang. (1998). The Cobras of the Genus Naja in India. Hamadryad. Vol. 23, No. 1, 15-32 pp.

- ↑ Jump up to: 12.0 12.1 Naja kaouthia: General Details at Clinical Toxinology. Accessed 22 June 2012.

- ↑ Chanhome, L, Jintkune, P., Wilde, H., Cox, M. J. (2001). Venomous snake husbandry in Thailand. Wilderness and Environmental Medicine 12: 17–23.

- ↑ Wei, J.-F., Lü, Q.-M., Jin, Y., Li, D.-S., Xiong, Y.-L., Wang, W.-Y. (2003). α-Neurotoxins of Naja atra and Naja kaouthia Snakes in Different Regions. Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 35 (8): 683–688.

- ↑ Ogay, A.; Rzhevskya, D. I., Murasheva, A. N., Tsetlinb, V. I., Utkin, Y. N. (2005). "Weak neurotoxin from Naja kaouthia cobra venom affects haemodynamic regulation by acting on acetylcholine receptors". Toxicon 45 (1): 93–99. DOI:10.1016/j.toxicon.2004.09.014. Retrieved on 22 June 2012. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Mahanta, M.; Mukherjee, A. K. (2001). "Neutralisation of lethality, myotoxicity and toxic enzymes of Naja kaouthia venom by Mimosa pudica root extracts". Journal of Ethnopharmacology 75 (1): 55–60. DOI:10.1016/S03788741(00)003731. Retrieved on 22 June 2012. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Fletcher, J. E.; Jiang, M.-S.; Gong, Q.-H.; Yudkowsky, M. L.; Wieland, S. J. (1991). "Effects of a cardiotoxin from Naja naja kaouthia venom on skeletal muscle: Involvement of calcium-induced calcium release, sodium ion currents and phospholipases A2 and C". Toxicon 29 (12): 1489–1500. DOI:10.1016/0041-0101(91)90005-C. Retrieved on 22 June 2012. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Fry, Dr. Bryan Grieg. LD50 Menu. Australian Venom Research Unit. University of Queensland. Retrieved on 22 June 2012.

- ↑ Engelmann, W.-E. (1981). Snakes: Biology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Leipzig; English version NY, USA: Leipzig Publishing; English version published by Exeter Books (1982), 51. ISBN 0-89673-110-3.

- ↑ Pratanaphon, R.; Akesowan, S., Khow, O., Sriprapat, S., Ratanabanangkoon, K. (1997). "Production of highly potent horse antivenom against the Thai cobra (Naja kaouthia)". Vaccine 15 (14): 1523–1528. DOI:10.1016/S0264-410X(97)00098-4. Retrieved on 22 June 2012. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Davidson, T.. Snakebite Protocols: Summary for Human Bite by Monocellate Cobra (Naja naja kaouthia).

- ↑ Gopalakrishnakone, Chou, P, LM (1990). Snakes of Medical Importance (Asia-Pacific Region). Singapore: Venom and Toxin Research Group National University of Singapore and International Society on Toxinology (Asia-Pacific section), 235. ISBN 9971-62-217-3.