Vietnam War

Template:TOC-right While there are background factors that go back to the rebellion, against China, of the Trung Sisters in the first century C.E., limits need to be set on the scope of the Vietnam War. There are important background details variously dealing with the start of French colonization in Indochina, including the present countries of Vietnam and Laos, the expansion of Japan into Indochina and the U.S. economic embargoes as a result, and both the resistance to Japanese occupation and the Vichy French cooperation in ruling Indochina.

In the West, the term is usually considered to have begun somewhere in the mid-20th century. There were at least two periods of hot war, first the Vietnamese war of independence from the French, including guerilla resistance starting during the Second World War and ending in a 1954 Geneva treaty that partitioned the country into the Communist North (NVN) (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRV) and non-Communist South (SVN) (Republic of Vietnam, RVN). A referendum on reunification had been scheduled for 1956, but never took place.

While Communists had long had aims to control Vietnam, the specific decision to conquer the South was made, by the Northern leadership, in May 1959. The DRV had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy, involving military, diplomatic, covert action and psychological operations to achieve those objectives. Whether or not one agreed with those objectives, there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions. Its military first focused on guerilla and raid warfare in the south, simultaneously improving the air defensives of the north.

In contrast, the Southern governments from 1954 did not either have popular support or tight control over the populace. There was much jockeying for power as well as corruption.

Eventually, following the Maoist doctrine of protracted war, the final "Phase III" offensive was by conventional forces, the sort that the U.S. had tried to build a defense against when the threat was from guerrillas. T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in the southern capital, Saigon, were not driven by ragged guerrillas.

Fighting gradually escalated from that point, with a considerable amount of covert Western action in Vietnam and Laos. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident, in which U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson claimed North Vietnamese naval vessels had attacked U.S. warships, open U.S. involvement began in 1964, and continued until 1972. After the U.S. withdrawal based on a treaty in Paris, the two halves were to be forcibly united, by DRV conventional invasion, in 1975.

This is not to suggest that 1945-1975 was the only conflict seen in the region. A Japanese invasion in 1941 triggered U.S. export embargoes to Japan, which affected the Japanese decision to attack Western countries in December 1941; see Vietnam, war, and the United States . Vietnamese nationalism goes back through the first French presence, but there was opposition to Chinese influence dating back to the Two Trung Sisters in the first century A.D.

From the perspective of some Vietnamese, the war was the military effort of the Communist Party of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh to defeat France (1946-54), and the same party, now in control of North Vietnam, to overthrow the government of South Vietnam (1958-75) and take control of the whole country, in the face of military intervention by the United States (1964-72). Others discuss the Viet Minh resistance, in the colonial period, to the French and Japanese, and the successful Communist-backed overthrow of the post-partition southern government, as separate wars. Unfortunately for naming convenience, there is a gap between the end of French rule and the start of partition in 1954, and the Northern decision to commit to controlling the South in 1959.

Without trying to name the wars, the key timeline events in modern history are:

- 1941: Japanese invasion of French Indochina

- 1945: End of World War II and return of Indochina to French authority

- 1954: End of French control and beginning of partition under the Geneva agreement; CIA covert operation started

- 1955: First overt U.S. advisors sent to the South

- 1959: North Vietnamese decision, in May 1959 to create the 559th (honoring the date) Transportation Group and begin infiltration of the South

- 1964: Gulf of Tonkin incident and start of U.S. combat involvement; U.S. advisors and support, as well as covert operations, had been in place for several years

- 1972: Withdrawal of last U.S. combat forces as a result of negotiation

- 1975: Overthrow of the Southern government by regular Northern troops, followed by reunification under a Communist government.

Tentative lists of subarticles to spin out (also see talk page) (names are working titles only)

- Vietnam, pre-colonial history

- Vietnam, French colonial period

- Vietnam War, World War II and immediate postwar

- Vietnam War, First Indochina War

- Vietnam War, Partition and decisions

- Vietnam war, Second Indochinese War, buildup before Gulf of Tonkin incident

- Vietnam, war, and the United States (emphasis on U.S. domestic politics)

- Gulf of Tonkin incident (in progress)

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, external allied combat forces in South Vietnam

- Operation ATTLEBORO, Battle of the Ia Drang, Battle of Bong Son, Operation JUNCTION CITY, Operation CEDAR FALLS, Battle of Khe Sanh, Tet Offensive, representative drafts at detailed level

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, air war in the North

- Operation FLAMING DART, Operation ROLLING THUNDER,Operation Bolo, Operation LINEBACKER I, Operation LINEBACKER II, representative drafts at detailed level

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, Vietnamization

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, fall of South Vietnam

To appreciate the complexity it is necessary to start with French colonialism in the 19th century, or, quite possibly, to go to Vietnamese drives for independence in the 1st century, with the Trung Sisters' revolt against the Chinese; the citation here mentions the 1968th anniversary of their actions.[1]

French Indochina Background

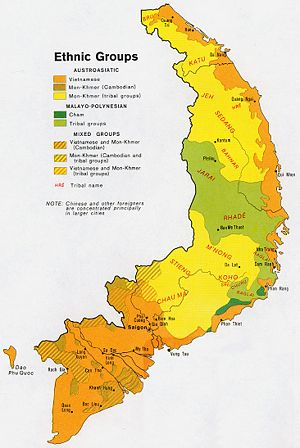

At the time of the French invasion, during the Second French Revolution with Louis Napoleon III as President, there were three parts of what is now Vietnam:

- Cochinchina in the south, including the Mekong Delta and what was variously named Gia Dinh, Saigon, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Annam in the center, but the mountainous Central Highlands, the home of the Montagnard peoples, considered itself autonomous

- Tonkin in the North, including the Red River Delta, Hanoi, and Haiphong.

In 1858, France invaded Vietnam, and the ruling Nguyen dynasty accepted protectorate status. Cambodia and Laos also came under French control. Danang, then called Tourane, was captured in late 1858 and Gia Dinh (Saigon and later Ho Chi Minh City) in early 1859. In both cases Vietnamese Christian support for the French, predicted by the missionaries, failed to materialize.

Vietnamese resistance and outbreaks of cholera and typhoid forced the French to abandon Tourane in early 1860. They returned in 1861, with 70 ships and 3,500 men to reinforce Gia Dinh and. In June 1862, Emperor Tu Duc, signed the Treaty of Saigon.

French naval forces under Admiral de la Grandiere, the governor of Cochinchina (as the French renamed Nam Bo), demanded and received a protectorate status for Cambodia, on the grounds that the Treaty of Saigon had made France heir to Vietnamese claims in Cambodia. In June 1867, he seized the last provinces of Cochinchina. The Siamese government, in July, agreed to the Cambodian protectorate in return for receiving the two Cambodian provinces of Angkor and Battambang, to Siam. Siam was never under French control.

With Cochinchina secured, French naval and mercantile interests turned to Tonkin (as the French referred to Bac Bo).

Indochina under the Third French Republic

With the collapse of Napoleon III, in 1870, as a result of the Franco-Prussian War, the French Third Republic formed, and lasted until the Nazi conquest in 1940. Most of the key actions that set the context into which the Empire of Japan moved into the region happened during this period, and in the immediate aftermath under the Vichy goverment.

Few Frenchmen permanently settled in Indochina. Below the top layer of imperial control, the civil service comprised French-speaking Catholic Vietnamese; a nominal "Emperor" resided in Hue, the traditional cultural capital in north central Indonesia.

Little industry developed and 80% of the population lived in villages of about 2000 population; they depended on rice growing. Most were nominally Buddhist; about 10% were Catholic. Minorities included the Chinese merchants who controlled most of the commerce, and Montagnard tribesmen in the thinly populated Central Highlands. Vietnam was a relatively peaceful colony; sporadic independence movements were quickly suppressed by the efficient French secret police.

Indochinese Communist Party forms

Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) and fellow students founded the Indochinese Communist Party in Paris in 1929, but it was of marginal importance until World War II.[2] In 1940 and 1941 the Vichy regime yielded control of Vietnam to the Japanese, and Ho returned to lead an underground independence movement (which received a little assistance from the O.S.S., the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency CIA).[3]

World War II

Indochina, a French colony in the spheres of influence of Japan and China, was destined to be drawn into the Second World War both through European and Asian events. See Vietnam War, World War II and immediate postwar. From 1946 to 1948, the French reestablished control, but, in 1948, began to explore a provisional government. While there is no clear start to what ended in 1954, the more serious nationalist movement was clearly underway by 1948.

First Indochinese War

While there is no universally agreed name for this period in the history of Vietnam, it is the period between the formation of a quasi-autonomous government within the French Union, up to the eventual armed defeat of the French colonial forces by the Viet Minh. That defeat led to the 1954 Geneva accords that split Vietnam into North and South.

The French first created a provisional government under Bao Dai, then recognized Vietnam as a state within the French Union. In such a status, France would still control the foreign and military policy of Vietnam, which was unacceptable to both Communist and non-Communist nationalists.

Partition and decisions: 1954 (post-French)-1959 (decision to invade)

- See also: Vietnam, war, and the United States

- See also: Vietnam War, Buddhist crisis and military coup of 1963

This period was begun by the military defeat of the French, with a Geneva meeting that partitioned Vietnam into North and South. Two provisions of the agreement never took place: a referendum on unification in 1956, and also banned foreign military support and intervention.

In the south, the Diem government was not popular, but there was no obvious alternative that would rise above factionalism, and also gain external support. Anti-Diem movements were not always Communist, although some certainly were.

The north was exploring its policy choices, both in terms of the south, and its relations with China and the Soviet Union. The priorities of the latter, just as U.S. and French priorities were not necessarily those of Diem, were not necessarily those of Ho. In 1959, North Vietnam made the explicit decision to overthrow the South by military means

1959-1964 (up to Gulf of Tonkin incident)

To put the situation in a strategic perspective, remember that North and South Vietnam were artificial constructs of the 1954 Geneva agreements. While there had been several regions of Vietnam, when roughly a million northerners, of different religion and ethnicity than in the south, migrated into a population of four to five million, there were identity conflicts. Communism has been called a secular religion, and the North Vietnamese government officials responsible for psychological warfare and prisoner-of-war indoctrination were Military Proselytizing cadre. Communism, for its converts, was an organizing belief system that had no equivalent in the South. At best, the southern leadership intended to have a prosperous nation, although leaders were all too often focused on personal prosperity. Their Communist counterparts, however, had a mission of conversion by the sword — or the AK-47 assault rifle.

Between the 1954 Geneva accords and 1956, the two countries were still forming; the influence of major powers, especially France and the United States, and to a lesser extent China and the Soviet Union, were as much an influence as any internal matters. There is little question that in 1957-1958, there was a definite early guerilla movement against the Diem government, involving individual assassinations, expropriations, recruiting, shadow government, and other things characteristic of Mao's Phase I. The actual insurgents, however, were primarily native to the south or had been there for some time. While there was clearly communications and perhaps arms supply from the north, there is little evidence of any Northern units in the South, although organizers may well have infiltrated.

It is now confirmed that North Vietnam made a firm commitment, May 1959, to war in the South. Diem, well before that point, had constantly pushed a generic anticommunism, but how much of this was considered a real threat, and how much a nucleus around which he justified his controls, is less clear. Those controls, and the shutdown of most indigenous opposition by 1959, was clearly alienating the Diem government from significant parts of the Southern population, was massively mismanaging rural reforms and overemphasizing the power base in the cities, and might have had an independent rebellion. North Vietnam, however, clearly began to exploit that alienation. The U.S., however, did not recognize a significant threat, even with such information as intelligence on the formation of the logistics structure for infiltration. The presentation of hard evidence — communications intelligence about the organization building the Ho Chi Minh trail — Hanoi's involvement in the developing strife became evident. Not until 1960, however, did the U.S. recognize both Diem was in danger, that the Diem structure was inadequate to deal with the problems, and present the first "Counterinsurgency Plan for Vietnam (CIP)"

It can be established that there was endemic insurgency in South Vietnam throughout the period 1954-1960. It can also be established-but less surely- that the Diem regime alienated itself from one after another of those elements within Vietnam which might have offered it political support, and was grievously at fault in its rural programs. That these conditions engendered animosity toward the GVN seems almost certain, and they could have underwritten a major resistance movement even without North Vietnamese help.

There is little doubt that there was some kind of Viet Minh-derived "stay behind" organization betweeen 1954 and 1960, but it is unclear that they were directed to take over action until 1957 or later. Before that, they were unquestionably recruiting and building infrastructure, a basic first step in a Maoist protracted war mode.

While the visible guerilla incidents increased gradually, the key policy decisions by the North were made in 1959. Early in this period, there was a greater degree of conflict in Laos than in South Vietnam. U.S. combat involvement was, at first, greater in Laos, but the activity of advisors, and increasingly U.S. direct support to South Vietnamese soldiers, increased, under U.S. military authority, in late 1959 and early 1960. Communications intercepts in 1959, for example, confirmed the start of the Ho Chi Minh trail and other preparation for large-scale fighting.

Guerilla attacks increased in the early 1960s, at the same time as the new John F. Kennedy administration made Presidential decisions to increase its influence. Diem, as other powers were deciding their policies, was clearly facing disorganized attacks and internal political dissent. There were unquestioned conflicts between the government, dominated by minority Northern Catholics, and both the majority Buddhists and minorities such as the Montagnards, Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao. These conflicts were exploited, initially at the level of propaganda and recruiting, by stay-behind Viet Minh receiving orders from the North.

Republic of Vietnam strategy

Quite separate from its internal problems, South Vietnam faced an unusual military challenge. On the one hand, there was a threat of a conventional, cross-border strike from the North, reminiscent of the Korean War. In the fifties, the U.S. advisors focused on building a "mirror image" of the U.S. Army, designed to meet and defeat a conventional invasion. [4]

Diem (and his successors) were primarily interested in using the ARVN as a device to secure power, rather than as a tool to unify the nation and defeat its enemies. Province and District Chiefs in the rural areas were usually military officers, but reported to political leadership in Saigon rather than the military operational chain of command. The 1960 "Counterinsurgency Plan for Vietnam (CIP)" from the U.S. MAAG was a proposal to change what appeared to be a dysfunctional structure. [4] Further analysis showed the situation was not only jockeying for power, but also reflected that the province chief indeed had security authority that could conflict with that of tactical military operations in progress, but also had responsibility for the civil administration of the province. That civil administration function became more and more intertwined, starting in 1964 and with acceleration in 1966, of the "other war" of rural development.[5]

Communist strategy

The North had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy, involving military, diplomatic, covert action and psychological operations to achieve those objectives. Whether or not one agreed with those objectives, there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions. Its military first focused on guerilla and raid warfare in the south (i.e., Mao's "Phase I"), simultaneously improving the air defensives of the north. By the mid-sixties, they were operating in battalion and larger military formation that would remain in contact as long as the correlation of forces was to their advantage, and then retreat &mdash Mao's "Phase II".

Eventually, following the Maoist doctrine of protracted war, the final "Phase III" offensive was by conventional forces, the sort that the U.S. had tried to build a defense against when the threat was from guerrillas. T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon were not driven by ragged guerrillas.

In the Viet Cong, and in the North Vietnam regular army (PAVN), every unit had political officers, or Proselytizing Cadre. The Viet Cong had many unwilling draftees of its own; tens of thousands deserted to the government, which promised them protection. The Viet Cong executed deserters if it could, and threatened their families, all the while closely monitoring the ranks for any sign of defeatism or deviation from the party line.[6]

Gulf of Tonkin incident

President Johnson asked for, and received, Congressional authority to use military force in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which was described as a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. warships. After much declassification and study, much of the incident remains shrouded in what Clausewitz called the "fog of war", but serious questions have been raised of whether the North Vietnamese believed they were under attack, who fired the first shots, and, indeed, if there was a true attack. Congress did not declare war, which is defined as its responsibility in the Constitution of the United States; nevertheless, it launched what effectively was the longest war in U.S. history -- and even longer if the covert actions before the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin situation is considered.

Changes in U.S. commitment following Johnson's election

Although the combination of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the political authority granted to Lyndon Johnson by being elected to the presidency rather than succeeding to it gave him more influence, and there was certainly an immense infusion of U.S. and allied forces into the theater of operations, never forget the chief participants in the war were Vietnamese.

Johnson's motives were different from Kennedy's, just as Nixon's motivations would be different from Johnson's. Of the three, Johnson was most concerned with U.S. domestic policy. He probably did want to see improvements in the life of the Vietnamese, but the opinions of his electorate were most important. His chief goal was implementing the set of domestic programs that he called the "Great Society". He judged actions in Vietnam not only on their own merits, but how they would be perceived in the U.S. political system. [7] To Johnson, Vietnam was a "political war" only in the sense of U.S. domestic politics, not a political settlement for the Vietnamese.

He was concerned about what was called the "falling domino" effect; he thought the fall of neighboring states would be rapid, but others looked for great damage in slow motion, as in a a 1964 CIA estimate:

We do not believe that the loss of South Vietnam and Laos would be followed by the rapid, successive communization of other states of Southeast Asia. Instead of a shock wave passing from one to the next, there would be a simultaneous, direct effect on all Far Eastern countries. With the possible exception of Cambodia, it is likely that no nation of the area would quickly succumb to communism as a result of the fall of Laos and South Vietnam. Further, a spread of communism in the area would not be inexorable, and any spread that would happen would take time — time in which the situation might change in any of a number of ways unfavorable to the Communist cause....The loss of South Vietnam and Laos to the Communists would be profoundly damaging to the US position in the Far East, most especially because the US has committed itself persistently, emphatically, and publicly to preventing Communist takeover of the two countries.[8]

1965

On 13 April 1965, joint RVN-US discussions agreed that the ARVN force levels were inadequate. The manning level was increased, to increase RVN infantry battalions from 119 (93 infantry, 20 Ranger, and 6 airborne) to 150. The new battalions were generally added to existing regiments, to avoid the need of creating more headquarters units. By the end of 1965, twenty-four were either in the field or in training areas.[9]

In July 1965, McNamara sent Johnson a set of notes proposing escalation of what he saw as a deteriorating situation in South Vietnam. "The situation in SVN is worse than a year ago (when it was worse than a year before that). After a few months of stalemate, the tempo of the war has quickened. . . . The central highlands could well be lost to the NLF during this monsoon season. Since June 1, the GVN has been forced to abandon six district capitals; only one has been retaken...The odds are less than even that the Ky government will last out the year. Ky is "executive agent" for a directorate of generals."[10]

McNamara saw the correlation of forces between the ARVN and the VC is quite unfavorable. "The Govt-to-VC ratio overall is now only a little better than 3-to-1, and in combat battalions little better than 1.5-to-1." A historical rule of thumb for counterinsurgency has been that a 10 to 1 ratio is desirable, but, like all rules of thumb, it is not applicable to all situations. Even a critic of that generalization, "indeed, that ratio was often cited by critics of the U.S. policy in Vietnam", who cite a number of other revolutionary wars where the insurgency was defeated by less overwhelming ratios (e.g., Eritrea against Ethiopia) or where an acceptable goal was partition (e.g., Second Sudanese Civil War), cite the conventional wisdom as primarily relevant to situations of ideological insurgency against a central government, such as the Communist takeover of Vietnam, where the insurgents want complete victory.[11] The current U.S. Army doctrine on counterinsurgency also recognizes there is no simple ratio, "During previous conflicts, planners assumed that combatants required a 10 or 15 to 1 advantage over insurgents to win. However, no predetermined, fixed ratio of friendly troops to enemy combatants ensures success in COIN...A better force requirement gauge is troop density, the ratio of security forces (including the host nation’s military and police forces as well as foreign counterinsurgents) to inhabitants...Twenty counterinsurgents per 1000 residents is often considered the minimum troop density required for effective COIN operations; however as with any fixed ratio, such calculations remain very dependent upon the situation." [12] None of these sources, however, see a 3:1 to 1.5:1 as favorable.

McNamara also observed that the Administration's approach to air war against the North, Rolling Thunder, had not " produced tangible evidence of willingness on the part of Hanoi to come to the conference table in a reasonable mood. The DRV/VC seem to believe that SVN is on the run and near collapse; they show no signs of settling for less than complete takeover."[10]

His concept of a desirable outcome, which would be more likely implicit than formally agreed by treaty; he distinguished between the domestic VC insurgency and the DRV. It also assumed that the government of South Vietnam (GVN) would have adequate popular support:

- VC stop attacks and drastically reduce incidents of terror and sabotage.

- DRV reduces infiltration to a trickle, with some reasonably reliable method of our obtaining confirmation of this fact.

- US/GVN stop bombing of NVN.

- GVN stays independent (hopefully pro-US, but possibly genuinely neutral).

- GVN exercises governmental functions over substantially all of SVN.

- Communists remain quiescent in Laos and Thailand.

- DRV withdraws PAVN forces and other NVNese infiltrators (not regroupees) from SVN.

- VC/NLF transform from a military to a purely political organization.

- US combat forces (not advisors or AID) withdraw.

To carry out this strategy, there would be several components of power, the first two coming from Johnson and McNamara, and the third one they had selected among alternatives from GEN Westmoreland, the U.S Marine Corps, and Ambassador Taylor:

- Air operations against NVN (Operation ROLLING THUNDER), flown primarily from outside SVN (i.e., bases in Thailand, U.S. aircraft carriers in the South China Sea, and some long-range aviation from Guam

- Bases in SVN, including military airfields able to provide U.S. and ARVN ground troops with adequate air support. These bases would be defended by U.S. troops

- Build up major U.S. major ground forces in 1965, then commit to pursuit and destruction of the enemy main units (i.e., not local guerilla forces and not having rural security as a high priority) in 1966-1967, with victory in 1968.

Operation ROLLING THUNDER

After his reelection, Johnson sent in the first American combat troops in March, 1965, to protect the air bases; he and McNamara saw air power as decisive, but they had a very different theory than the JCS.

Johnson and McNamara, however, had launched an alternative air power strategy called Operation ROLLING THUNDER, nased entailed retaliatory bombing anytime Communists struck at American forces, together with a gradual buildup of 22 bombing attacks against small military targets in the North, in complete opposition to the JCS recommendations that if there were to be air strikes, they be intense.

Despite some shortages, the US Army had never been in nearly as good shape at the start of a war. At peak Westmoreland had 100 infantry battalions, the main maneuver and fighting unit of the war. Routinely it received 500 hours a month of helicopter support from corps' command. Above the battalion were brigades and divisions; in this war they handled paperwork, letting the battalions do the fighting. Overall, 20% of the soldiers were in "teeth" (combat) roles; the rest were "tail," assigned to advisory missions, logistics, maintenance, construction, medicine and administration.

Westmoreland's first challenge was figuring out a strategy to defeat the Viet Cong.

- Phase I: stabilize the situation (by the end of 1965)

- Phase II: (scheduled for 1966-67) would push the enemy back in key areas

- Phase III: total victory (1968)

Westmoreland's attritional strategy

His strategy conflicted with alternatives from the U.S. Marines (both the III Marine Amphibious Force in the northern South Vietnamese I Corps, as well as the higher command of the U.S. Marine Corps, and from Maxwell Taylor, U.S. Ambassador to the Republic of Vietnam, former [[Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff) and General, U.S. Army. He also was suggesting to fight a war of attrition against a Communist force guided by the Maoist doctrine of Protracted War, which specifically included attrition as one strategic option. [13]

Westmoreland's "ultimate aim", was:

"To pacify the Republic of [South] Vietnam by destroying the VC—his forces, organization, terrorists, agents, and propagandists—while at the same time reestablishing the government apparatus, strengthening GVN military forces, rebuilding the administrative machinery, and re-instituting the services of the Government. During this process security must be provided to all of the people on a progressive basis." Source: Directive 525-4 (MACJ3) 17 September 1965: Tactics and Techniques for Employment of US Forces in the Republic of Vietnam [14]

Westmoreland complained that, "we are not engaging the VC with sufficient frequency or effectiveness to win the war in Vietnam." He said that American troops had shown themselves to be superb soldiers, adept at carrying out attacks against base areas and mounting sustained operations in populated areas. Yet, the operational initiative— decisions to engage and disengage—continued to be with the enemy. [14]

To do this, he needed larger forces. which, after negotiations with McNamara, would constitute 47 U.S. maneuver battalions, plus supporting air and artillery. He would gain 27 battalions in 1966; the total allied force would consist of 150 ARVN and 47 US infantry battalions in 1966.

On July 28, President Johnson would announce the large-scale commitment of another 44 battalions; at least 4 battalions, plus support elements, had been sent in the previous few months.

Westmoreland vs. Marines

The Marines, with responsibility for "I Corps," the northern third of the country, had a plan for Phase I. It reflected their historic experience in pacification programs in Haiti and Nicaragua early in the century. [15]

Noting that 80% of the population lived in 10% of the land, they proposed to separate the Viet Cong from the populace. It was a major challenge, since the NLF controlled the great majority of villages in I Corps. Working outward from Da Nang and two other enclaves, 25,000 Marines of the III Marine Amphibious Force[16] systematically eliminated Viet Cong soldiers and guerrilla forces, and sought to weed out NLF cadres from the villages.

The main device was the Combined Action Platoon, with a 15-man rifle squad and 34 local militia. Rather than having separate "advisory" units, the bulk of the CAP members served alongside the local militia, building personal relationships. It would "capture and hold" hamlets and villages. The Marines put heavy stress on honesty in local government, land reform (giving more to the peasants) and MEDCAP patrols that offered immediate medical assistance to villagers. In some respects, the CAP volunteers had assignments similar to the much more highly trained United States Army Special Forces, but they would make use of whatever skills they had. One young Marine, for example, was a graduate of a high school in an agricultural area in the U.S., came from a family hog farm that went back several generations, and won competitions for teenagers who raised prized hogs. While he was no military expert, he was recognized as helping enormously with the critical pork production in villages.

Marines in CAP had the highest proportion of volunteering for successive Vietnam tours of any branch of the Marine Corps. Many villages considered the CAP personnel part of their extended family. Westmoreland distrusted the Marine village-oriented policy as too defensive for Phase II--only offense can win a war, he insisted. The official slogan about "winning hearts and minds" gave way to the Army's "Get the people by the balls, and their hearts and minds will follow." Ambassador Taylor welcomed the Marine strategy as the best solution for a basically political problem; it would also minimize American casualties.[17]

While the Army and Marines had their approaches to the village, yet another came from a joint project of the CIA and United States Army Special Forces. The CIDG (Civilian Irregular Defense Groups) program was created for the Montagnard peoples in the sparsely populated mountanous areas of the Central Highlands. The Montagnards disliked all Vietnamese, and had supported first the French, then the Americans. About 45,000 were enrolled in militias whose main role was defending their villages from the Communists. In 1970 the CIDG became part of the ARVN Rangers.[18] Indeed, the tensions were high between the Army (which was in charge) and the Marines.

Westmoreland vs. Taylor

Taylor's strategy was to use superior American mobility and firepower to locate, attack and destroy the Viet Cong main forces. Once they were destroyed, he reasoned, the villages would be easy to pacify. Westmoreland proposed instead a "search and destroy" strategy that would win the war by attrition. The idea was to track down and fight the larger Viet Cong units, hoping to grind them down faster than they could be replaced. The measure of success in a war of attrition was not battles won or territory held or villages pacified, it was the body count of dead enemy soldiers. The body counts often were demanded by the chain of command, under pressure from Washington, even though the numbers were guesses and had little to do with realistic battle damage assessment. A number of field commanders and CIA analysts found that a much better predictor was the number of weapons recovered from a battlefield.

Westmoreland promised his three phase strategy could get the job done--whereas the defensive enclaves would prolong the conflict indefinitely into the future. Johnson could not wait forever, so he bought Westmoreland's plan and removed Taylor.

Air war in the south

Vietnamese jungle caused much military difficulty. In the 1964 election, Barry Goldwater never recovered from speculation about possibility of using low-yield nuclear weapons to defoliate infiltration routes in Vietnam, he never actually advocated the use of nuclear weapons against the North Vietnamese. Nevertheless, the Democrats easily painted Goldwater as a warmonger who would drop atomic bombs on Hanoi.[19]

Under Operation RANCH HAND, the U.S. military sprayed large areas with a defoliant called Agent Orange. While Agent Orange itself was considered nontoxic to humans, and was primarily composed of conventional herbicides 2,4-D and 2,4,5-T, many batches had an exceptionally toxic byproduct of the manufacturing process, which caused caused significant contamination, and long-term health consequences, including defects, on both Vietnamese and Americans. This was also used by Canadian Forces in Canada, who documented the later-understood health effects. [20]

Moscow sent in sophisticated air defense systems; 922 planes went down. Rolling Thunder dropped 640,000 tons of bombs, but pilots protested angrily that political restrictions radically reduced their effectiveness. As one Navy flier growled in his diary:

We fly a limited aircraft, drop limited ordnance, on rare targets in a severely limited amount of time. Worst of all we do this in a limited and highly unpopular war....What I've got is personal pride pushing against a tangled web of frustration.[21]

Rolling Thunder did reduce the southward flow of arms somewhat, and definitely forced Hanoi to divert more and more of its resources to logistics, air defense and rebuilding. More than half of the North's electric power, oil storage, bridges and railroad yards had to be rebuilt. Supplies were hidden in small caches or buried underground, which further attenuated Hanoi's logistics capability. The suffering of its people held a lower priority for the Politburo than its quest for victory, and its actions were consistent with its goals, especially considered in Mao's concept of protracted war.

After Nixon replaced Johnson, the new national security team reviewed the situation. Henry Kissinger asked the Rand Corporation to provide a list of policy options, prepared by Daniel Ellsberg. On receiving the report, Kissinger and Schelling asked Ellsberg about the apparent absence of a victory option; Ellsberg said "I don't believe there is a win option in Vietnam." While Ellsberg eventually did send a withdrawal option, Kissinger would not circulate something that could be perceived as defeat. [22].

Action-reaction under ROLLING THUNDER plan

On February 6, the VC attack U.S. facilties at Pleiku, killing 8 and destroying 10 aircraft. President Johnson, on February 7-8, responded with the first specifically retaliatory air raid, Operation FLAMING DART (or, more specifically, FLAMING DART I), of the broader Operation ROLLING THUNDER plan, which had not yet officially started. He made no public announcements, although the U.S. press reported it. The attack was carried out by U.S. Navy aviators from an aircraft carrier in the South China Sea. FLAMING DART II was a response to an attack on Qui Nhon on March 10. In response, initially unknown to the U.S., the North Vietnamese received their first S-75 Dvina (NATO reporting name SA-2 GUIDELINE) surface-to-air missiles, starting an upward spiral of air attack and air defense.

He approved the sustained Operation ROLLING THUNDER plan on March 13.

On March 8, in response to Westmoreland's request of February 22 reflecting a concern with VC forces massing near the Marine air base at Da Nang, 3500 Marine ground troops arrived, the first U.S. large ground combat unit in Vietnam. In April, he authorized the deployment of an additioal two Marine battalions and up to 20,000 support personnel. Again without public announcement, he changed the rules of engagement to permit the Marines to go beyond static defense, and to start offensive sweeps to find and engage enemy forces.

His main public announcement at the time, however, was an April 7 speech, in which he offered economic support to North Vietnam, and Southeast Asia in general, if it would stop military action. [23] This offer was quite in keeping with his goals for development, the Great Society, in the United States, and was likely a sincere offer. That he saw such an offer as attractive to the enemy, however, is an indication of his lack of understanding of the opposing ideology.

More elaboration of the proposal was in National Security Action Memorandum 329 [24] This initially classified (but at the lowest level) document, among other things, asked for specific recommendations of a "reviews of the pros and cons" of increasing U.S. aid even before a regional development program started.

First Airmobile Battles: Ia Drang and Bong Son

Giap's new plan was to use three regiments, but with a new controlling divisional headquarters, across the neck of SVN, cutting the country in two. The division threatened the Plei Me special forces camp with one regiment, but put a second regiment across the road over which South Vietnamese forces, without helicopters, would have to drive to Plei Me from the larger base in Pleiku. Intelligence identified the presence, but at first not the position, of a third regiment, which could attack Pleiku if the reserve based there went to the assistance of Plei Me.

The PAVN preferred hit-and-run ambushes, or what they called "catch and grab." When their retreat was blocked, their next tactic was called "hugging the belt" [25] the Americans hesitated to use artillery and gunships because of the risk of friendly fire casualties. The surprise attack would give a short window of opportunity before superior American mobility could be brought to bear. Moore's after-action reports suggested that "danger close" air and artillery could be a reasonable calculated risk when used competently.

The South Vietnamese recognized they were stretched too thin, and asked for U.S. help. The U.S. Field Force (corps equivalent) commander for the area, MG Stanley Larsen, told GEN Westmoreland that he thought the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) was ready, and got permission for it to use its mobility to bypass the road ambushes. Since the PAVN along the road had planned to ambush trucks, there was not an issue of not being able to find the relieving troops. Helicopters could be heard, but their landing zones were unpredictable until they actually landed — fake landings were not uncommon. In the Battle of the Ia Drang, the first true airmobile force met PAVN regulars.

It should be noted that the PAVN's practice of listening for helicopters was realized by Harold Moore, promoted to brigade command after leading a battalion in the Ia Drang. In the larger Battle of Bong Son approximately a month later, which extended into 1966, Moore used obvious helicopters to cause the PAVN to retreat onto very reasonable paths to break away from the Americans — but different Americans had silently set ambushes, earlier, across those escape routes.

Heavy doses of tactical air power, including area, then radar-controlled saturation bombing from B-52s, overwhelmed the PAVN. The invasion was stopped; the survivors fled back into their Cambodian sanctuaries. Airmobile techniques proved sufficiently important that the 101st Airborne Division converted to an true airmobile formation like that of the 1st Cavalry Division, but other U.S. main units would have helicopters attached for pecific missions. Needs sourcing Giap excused his failure by saying he only wanted to discover the American's tactics; he convinced the Politburo that it was necessary to return to low-level guerrilla tactics because he could not beat the Americans in battle.

The results of Westmoreland's attritional strategy

Needs explanation and sourcing Of two million small unit operations, 99% never encountered the enemy. What are now called improvised explosive devices or "booby traps" at the time, and Mine (land warfare)#land mines together caused a third of American deaths. [26]

The war was fought out in the other one percent, and most of the time combat was initiated by Communist forces. The "hot landing zone" (enemy attacking choppers as they landed) accounted for 13% of the fights. American platoons on patrol were hit by ambush in 23% of the engagements, and their camps were hit by rocket or grenade attacks in 30%. In 27% of the battles the Americans took the initiative, including 9% ambushes, 5% planned attacks on known positions, and 13% attacks on unsuspected enemy positions. In 7% of the engagements both sides were surprised as they stumbled upon each other in the jungle.

By the end of the war, 30,600 soldiers and 12,900 Marines had been killed in combat, together with 1,400 sailors and Navy pilots, and 1,000 Air Force fliers. As is classic guerilla doctrine, when units with heavier power arrived, the weaker force dispersed. By American standards, they could not win, they could scarcely replace their losses, yet they kept trudging down the Ho Chi Minh Trail day after day. Given that the current government of Vietnam is directly descended from the same government that Westmoreland claimed he would defeat by attrition, his analysis was demonstrated to be incorrect. His deputy and immediate successor, GEN Creighton Abrams, changed strategies when he took command of MACV, to a broader strategy that put as much emphasis on securing and building the countryside as it did killing the main force.

With more aggressive pursuit, including airmobile operations (see also Vietnam War Ground Technology, Westmoreland's tactics worked in terms of defeating the threat of larger enemy units (i.e., battalion or larger) to South Vietnam.

The Viet Cong dispersed into smaller and smaller units, and so too did the US forces, until they were running platoon and even squad operations that blanketed far more of the countryside, chasing the fragmented enemy back into remote, uninhabited areas or out of the South altogether. Not only low-level NLF sympathizers but even Viet Cong officers and NLF political cadres started to surrender, accepting the resettlement terms offered by the GVN. At the end of 1964, the Pentagon estimated that only 42% of the South Vietnamese people lived in cities or villages that were securely under GVN control. (20% were in villages controlled by the NLF, and 37% were in contested zones.) At the end of 1967, 67% of the population was "secure," and only a few remote villages with less than 2% of the population were still ruled by the NLF.

1966

1966 was the year of considerable improvement of command relationships, still under Westmoreland, for what Westmoreland considered the less interesting "other war" of rural development. There were frequent changes of names of aspects of this mission, starting in 1964, but eventually, the GVN and US agreed on the term Revolutionary Development (RD), which was to continue in a variety of development activities. The term, apparently coined by Premier and general Nguyen Cao Ky, was agreed to be defined as

RD is the integrated military and civil process to restore, consolidate and expand government control so that nation building can progress throughout the Republic of Vietnam. It consists of those coordinated military and civil actions to liberate the people from Viet Cong control; restore public security; initiate political, economic and social development; extend effective Government of Vietnam authority; and win the willing support of people toward these ends.[27]

"Search and Destroy" gave way after 1968 to "clear and hold", when Creighton Abrams replaced Westmoreland.

Pacification/Revolutionary Development

Westmoreland was principally interested only in overt military operations, while Abrams looked at a broader picture. MACV advisors did work closely with 900,000 local GVN officials in a well-organized pacification program called CORDS (Civil Operations and Revolutionary Development.) It stressed technical aid, local self government, and land distribution to peasant farmers. A majority of tenant farmers received title to their own land in one of the most successful transfer projects in any nation. On the other hand, hundreds of thousands of peasants entered squalid refugee camps when CORDS moved them out of villages that could not be protected.[28] In the Phoenix Program (part of CORDS with a strong CIA component) GVN police identified and arrested (and sometimes killed) the NLF secret police agents engaged in assassination.

1967

General Nguyen Van Thieu (1923-2001), a competent, Catholic, became president (in office 1967-75). The NLF failed to disrupt the national legislative election of 1966, or the presidential elections of 1967, which consolidated Thieu-ARVN control over GVN. Thieu, however, failed to eliminate the systematic internal inefficiencies and corruption the ARVN.

Ground combat

Throughout the first five months, in I Corps, there was heavy bombardment of U.S. bases from PAVN units in the DMZ.

Search-and-destroy missions in the Saigon area began early in the year, beginning with the 19-day Operation CEDAR FALLS, in the Iron Triangle, followed by 72 days of Operation JUNCTION CITY, beginning in February.

Air war

In April, attacks began on all but one of the North Vietnamese fighter airfields; Phuc Yen, the international airport, remained off limits. Approximately half of the North Vietnamese fighters were shot down in May.

1968

While there have been exceptions, especially in recent wars, Marines and Army troops do not always mix well, as they have some very different doctrinal assumptions. Army troops have much heavier artillery, and will wait for it to suppress the enemy before attacking on the ground, while Marines rely both on fast movement, and their own air support substituting for heavy artillery (i.e.,Marine Air-Ground Task Forces, which put land and air elements under a common commander). In 1968, Westmoreland sent his deputy Creighton Abrams to take command of I Corps, and gave his Air Force commander control of Marine aviation. The Marines protested vehemently but were rebuffed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.

The flow rose from 3,000 a month in 1965 to 8,000 a month throughout 1966 and 1967, and then 10,000 in 1968. By November 1965 the enemy had 110 battalions in the field, with 64,000 combat troops, 17,000 in combat support, and 54,000 part- time militia.

Psychological tension and breakdown of discipline

The more the American soldiers worked in the hamlets, the more they came to despise the corruption, inefficiency and even cowardice of GVN and ARVN. The basic problem was that despite the decline of the NLF, the GVN still failed to pick up popular support. Most peasants, refugees and city people remained alienated and skeptical. The superior motivation of the enemy troubled the Americans (especially in contrast with South Koreans, who fought fiercely for their independence.) "Why can't our Vietnamese do as well as Ho's?" Soldiers resented the peasants (ridiculing them as "gooks") who seemed sullen, unappreciative, unpatriotic and untrustworthy. The Viet Cong resorted more and more to booby-traps that (during the whole war) killed about 4,000 Americans and injured perhaps 30,000 (and killed or injured many thousands of peasants.)

It became more and more likely that after an ambush or boobytrap angry GIs would take out their frustrations against the nearest Vietnamese. In March 1968, just after the Tet offensive, one Army company massacred several hundred women and children at the hamlet of My Lai. High ranking American officers wre not charged, but the company captain was tried and acquitted. Platoon commander Lt. William Calley was sentenced to life imprisonment by a 1971 court martial. His sentence was reduced and he was released in 1975. The case became a focus of national guilt and self-doubt, with antiwar leaders alleging there were many atrocities that had been successfully covered up.[29]

Other factors contributed to reduced U.S. discipline and efficiency. Recreational drugs were readily available; this may not have been critical in rear areas, but a combat patrol cannot afford any reduction of its situational awareness. General social changes, including racial tension, also challenged authority. Fragging, or killing one's leader with a fragmentation grenade, sometimes was a response to a crackdown on rebellion, but, in some cases, it was a way to remove a thoroughly incompetent leader that could get his men killed.

Marine control of I Corps supplanted

By mid-January 1968, III MAF was the size of a U.S. corps, consisting of what amounted to two Army divisions, two reinforced Marine Divisions, a Marine aircraft wing, and supporting forces, numbering well over 100,000. GEN Westmoreland believed that Marine LTG Robert E. Cushman, Jr., who had relieved General Walt, was "unduly complacent."A Soldier Reports</ref> worried about what he perceived as the Marine command's ``lack of followup in supervision, its employment of helicopters, and its generalship. [30]Westmoreland sent his deputy Creighton Abrams to take command of I Corps, and gave his Air Force commander control of Marine aviation. The Marines protested vehemently but were rebuffed by the Joint Chiefs of Staff.[31]

Khe Sanh

As a diversion, PAVN sent a corps-strength unit to start the Battle of Khe Sanh, at what had been an isolated U.S. Marine location. Johnson personally took control of the defense. When the media back home warned darkly of another disaster like Dien Bien Phu, LBJ made his generals swear they would never surrender Khe Sanh. They committed 5% of their ground strength to the outpost (about 6,000 men) and held another 15-20% in reserve just in case. The enemy was blasted with 22,000 airstrikes and massive artillery bombardments. When the siege was lifted, the Marines had lost 205 killed, the PAVN probably 10,000.[32]

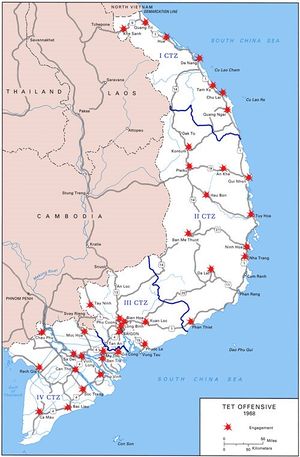

Tet Offensive

Hoping that Khe Sanh had tied down Westmoreland, the PAVN and Viet Cong struck on January 31, throwing 100,000 regular and militia troops against 36 of 44 provincial capitals and 5 of 6 major cities. They avoided American strongholds and targeted GVN government offices and ARVN installations, other than "media opportunities" such as attempting to a fight, by a small but determined squad, of the U.S. Embassy.

In February 1968, during the truce usually observed during the "Tet" holiday season, Hanoi attempted to destroy the government of South Vietnam an incite a popular uprising. It was decisively defeated by U.S. standards, as it had been apparently defeated again and again.[33] However, the Tet Offensive had a devastating impact on Johnson's political position in the U.S., and in that sense was a strategic victory for the Communists.[34]

The harshest fighting came in the old imperial capital of Hue. The city fell to the PAVN, which immediately set out to identify and execute thousands of government supporters among the civilian population. The allies fought back with all the firepower at their command. House to house fighting recaptured Hue on February 24. In Hue, Five thousand enemy bodies were recovered, with 216 U.S. dead, and 384 ARVN fatalities. A number of civilians had been executed while the PAVN held the city.

Nationwide, the enemy lost tens of thousands killed, US lost 1,100 dead, ARVN 2,300. The people of South Vietnam did not rise up. Pacification, however, suspended in half the country, and a half million more people became refugees. Despite the enormous damage done to the GVN at all levels, the NLF was in even worse shape, and it never recovered.

1969

Nixon and his chief adviser Henry Kissinger were basically "realists" in world affairs, interested in the broader constellation of forces, and the biggest powers. H Melvin Laird, Nixon's Secretary of Defense, was a career politician keenly aware that Americans had soured on the war. His solution was to make troop withdrawal announcements a measure of the administration's progress. Laird worried that further involvement would postpone modernization of the military and hasten the deterioration of morale.

Nixon's plan to end the war was to make it irrelevant, by moving the basic American strategy from containment to detente based on a realistic and limited view of the nation's own interests. Strategic nuclear deterrence was necessary. Since Western Europe was considered critical to U.S. interests, NATO would continue as a safeguard against Warsaw Pact attack. However, the US would seek detente, even friendship, with both the Soviet Union and China, would try to stop the arms race, and would tell countries threatened by subversion to defend themselves.

By 1969 Saigon forces were able to sustain the pressure on the NLF and Viet Cong and dramatically expand their control over both population and territory.[35] Indeed, for the first time GVN found itself in control of more than 90% of the population. The Tet objectives were beyond our strength, concluded General Tran Van Tra, the commander of Vietcong forces in the South:

We suffered large sacrifices and losses with regard to manpower and materiel, especially cadres at the various echelons, which clearly weakened us. Afterwards, we were not only unable to retain the gains we had made but had to overcome a myriad of difficulties in 1969 and 1970.[36] [37]

Air attacks on Cambodia

In 1969, Nixon ordered B-52 strikes against PAVN supply routes in Cambodia. The orders for U.S. bombing of Cambodia were classified, and thus kept from the U.S. media and Congress. In a given strike, each B-52 normally dropped 42,000 pounds of bombs, and the strike consistedflying in groups of 3 or 6. Surviving personnel in the target area were apt to know they had been bombed, and, since the U.S. had the only aircraft capable of that volume, would know the U.S. had done it.

The "secrecy" may have been meant to be face-saving for Sihanouk, but there is substantial reason to believe that the secrecy, in U.S. military channels, was to keep knowledge of the bombing from the U.S. Congress and public. Actually, a reasonable case could be made that the bombing fell under the "hot pursuit" doctrine of international law, where if a neutral (Sihanouk) could not stop one country from attacking another from the neutral sanctuary, the attacked country(ies) had every right to counterattack.

Intelligence and security

The first American soldier to die in Vietnam was a member of a communications intelligence unit. The U.S. intelligence collection systems, a significant amount of which (especially the techniques) were not shared with the ARVN, and, while not fully declassified, examples have been mentioned earlier in this article. The Communist side's intelligence operations, beyond the spies that were discovered, are much less known.

While there had been many assumptions that the South Vietnamese government was penetrated by many spies, and there indeed were many, a December 1969 capture of a Viet Cong communications intelligence center and documents revealed that they had been getting a huge amount of information using simple technology and smart people, as well as sloppy U.S. communications security. [38] This specific discovery was by U.S. Army infantry, with interpretation by regular communications officers; the matter infuriated GEN Abrams &mdash at the communications specialists. Before and after, there had been a much more highly classified, and only now available in heavily censored form, National Security Agency analysis of how the Communists were getting their information, which has led to a good deal of modern counterintelligence and operations security. [39]

Some of the material from Touchdown also gave insight into the North Vietnamese intelligence system. For example, the NVA equivalent of the Defense Intelligence Agency was the Central Research Directorate (CRD) in Hanoi. COSVN intelligence staff, however, disseminated the tactically useful material. [40] Their espionage was under the control of the Military Intelligence Sections (MIS), which were directed by the Strategic Intelligence Section (SIS) of CRD.

1970

Nixon's larger strategy was to convince Moscow and Bejing they could curry American favor by reducing or ending their military support of Hanoi. He assumed that would drastically reduce Hanoi's threat. Second, "Vietnamization" would replace attrition. Let the Vietnamese fight and die for their own freedom. Vietnamization meant heavily arming the ARVN and turning all military operations over to it; all American troops would go home.

Henry Kissinger began secret talks with the North Vietnamese official, Le Duc Tho, in February 1970. [41]

Cambodia

General Lon Nol overthrew Prince Norodom Sihanouk in March 1970, creating a new governement that was, in turn, overthrown by the Communist Khmer Rouge on April 1975.

Responding to a Communist attempt to take Cambodia, Nixon in April 1970 authorized a large scale US-ARVN incursion into Cambodia to directly hit the PAVN headquarters and supply dumps. The forewarned PAVN had evacuated most of their soldiers, but they lost a third of its arms stockpile, as well as a critical supply line from the Cambodian port of Sihanoukville. The incursion prevented the immediate takeover by Pol Pot and his Khmer Rouge. Pot broke with his original North Vietnamese sponsors, and aligned with China. This made American involvement visible to the U.S. population, and there were intense protests, including deaths in a confrontation between rock-throwing protesters and poorly-trained National Guardsmen at Kent State University.

The two dissenters to Nixon's plan were Saigon and Hanoi. President Thieu was, reasonably, concerned his fragile nation would not survive American withdrawal. Hanoi intended to conquer the South, with or without its Soviet and Chinese allies. It did start negotiations. believing the sooner the Americans left the better.

With the Viet Cong forces depleted, Hanoi sent in its own PAVN troops, and had to supply them over the Ho Chi Minh Trail despite systematic bombing raids by the B-52s. American pressure forced Hanoi to reduce its level of activity in the South.

Attempted POW rescue

1971

During the quiet year 1971, Hanoi was building up forces for conventional invasion, while Nixon sent massive quantities of hardware to the ARVN, and gave Thieu a personal pledge to send air power if Hanoi invaded. In 1971 all remaining American combat ground troops left, though air attacks continued.

The NLF and Viet Cong had largely disappeared. They controlled a few remote villages, and contested a few more, but the Pentagon estimated that 93% of the South's population now lived under secure GVN control.

The Vietnamization policy achieved limited rollback of Communist gains inside South Vietnam only, and was primarily aimed at providing the arms, training and funding for the South to fight and win its own war, if it had the courage and commitment to do so. By 1971 the Communists lost control of most, but not all, of the areas they had controlled in the South in 1967. The Communists still controlled many remote jungle and mountain districts, especially areas that protected the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Saigon's effort to strike against one of these strongholds, Operation Lam Son 719, was a humiliating failure in 1971. The SVN forces, with some U.S. air support, were unable to defeat PAVN regulars.

Allied ground troops depart

Most U.S. troops had withdrawn by the end of 1972, although there was a final period of intense bombing that led to the formal RVN-US-DRV agreement and prisoner release on January 27, 1973. [42] Other than a platoon of embassy guards who left in 1973, the last Australian combat units left in December 1972; the Australian formally ended Australian participation on January 11, 1973. [43]

1972

In March, 1972 Hanoi invaded at three points from north and west with 120,000 PAVN regulars spearheaded by tanks. This was conventional warfare, reminiscent of North Korea's invasion in 1950. They expected the peasants to rise up and overthrow the government; they did not. They expected the South's army to collapse; instead the ARVN fought very well indeed. Saigon had started to exert itself; new draft laws produced over one million well-armed regular soldiers, and another four million in part-time, lightly armed self-defense militia.

Eastertide invasion

North Vietnam began preparing the battlefield for its major invasion, by establishing an air defense network to protect what was to be their rear areas, north of the DMZ. This included S-75 Dvina (NATO reporting name SA-2 GUIDELINE) surface-to-air missiles that shot down three U.S. fighter-bombers in February.[44]

The main attack came with the start of the monsoon season, which prevented close air support and even good artillery fire control.

Operations in the North (RVN I Corps area)

The northern operation, launched on March 31, used three divisions for the attack, followed later by another three divisions. The PAVN 308th & 304th Divisions moved into Quang Tri province, followed by the 324B division attacking ARVN positions west of Hue.

Facing them was the newly formed 3rd ARVN Division, reinforced with the 147th Marine Brigade, 1st Airbone Brigade (detached from the Airborne Division), and 5th Armored Brigade. This was an odd mixture of troops for a critical area; the 3rd Division had only one regiment of experienced soldiers, while its other two regiments were made up of troops "who had been sent to the northernmost province of SVN as a punishment."[45] While the RVN Marines and Airborne had excellent reputations, this did not even comply with the 1975 "light at the top, heavy at the bottom" force dispositions. An army may place low-quality troops on a border, to pin the enemy while more powerful and mobile units maneuver for a counterattack.

These forces fell back, first to Dong Ha. They then linked to a defense line manned by the rest of the Airborne Division and another Marine brigade, south of the My Chanh River.

Operations in Central Vietnam (RVN II Corps)

Operations in the Saigon arrea (RVN III Corps)

May stabilization

Improvements in the weather allowed the U.S. to interdict the PAVN supply lines, and their offensive slowed; they moved back to secure an area south of the DMZ. This area was proclaimed under the control of the "Provisional Revolutionary Government of South Vietnam" (PRG). it welcomed diplomats from the Communist world, including Fidel Castro, and served as one of the launch points of the 1975 invasion.[46] [47] The PRG areas now contained five PAVN divisions. [48]

July counterattack

Some ground north of My Chanh was regained by the Airborne Division on the East and Marine Division on the West.

On September 14, the RVN Marines reentered Quang Tri.

The RVN relaxes

After the failed Easter Offensive the Thieu government made a fatal strategic mistake, going to a static defense and not refining its command and control for efficiency, not political reward. The departure of American forces and American money lowered morale in both military and civilian South Vietnam. Desertions rose as military performance indicators sank, and no longer was the US looking over the shoulder demanding improvement.

On other side, the PAVN had been badly mauled--the difference was that it knew it and it was determined to rebuild. Discarding guerrilla tactics, Giap three years to rebuild his forces into a strong conventional army. Without constant American bombing it was possible to solve the logistics problem by modernizing the Ho Chi Minh trail with 12,000 more miles of roads, as well as a fuel pipeline along the Trail to bring in gasoline for the next invasion.[49]

LINEBACKER II

Late in 1972 election peace negotiations bogged down; Thieu demanded concrete evidence of 's promises to Saignon. Nixon thereupon unleashed the full fury of air power to force Hanoi to come to terms. Operation Operation LINEBACKER II, in 12 days smashed many targets in North Vietnam cities that had always been sacrosanct. 59 key targets were attacked, often using new weapons. In particular, precision guided munitions destroyed bridges previously resistant to attack. US policy was to try to avoid residential areas; the Politburo had already evacuated civilians not engaged in essential war work.

The Soviets had sold Hanoi 1,200 S-75 Dvina/NATO: SA-2 GUIDELINE surface-to-air missiles (SAM) that proved effective against the B-52s for the first three days. In a remarkable display of flexibility, the Air Force changed its bomber tactics overnight--and Hanoi ran out of SAMs. An American negotiator in Paris observed that, "Prior to LINEBACKER II, the North Vietnamese were intransigent... After LINEBACKER II, they were shaken, demoralized, and anxious to talk about anything." Beijing and Moscow advised Hanoi to agree to the peace accords;they did so on January, 23, 1973.

The Air Force interpreted the quick settlement as proof that unrestricted bombing of the sort they had wanted to do for eight years had finally broken Hanoi's will to fight; other analysts said Hanoi had not changed at all.[50][51][52]

Peace accords and invasion, 1973-75

Peace accords were finally signed on 27 January 1973, in Paris. There would be an immediate in-place permanent cease-fire. The U.S. agreed to withdraw all its troops in 60 days (but could continue to send military supplies); North Vietnam was allowed to keep its 200,000 troops in the South but was not allowed to send new ones. Prisoners were exchanged. Although a low-intensity war continued, the world rejoiced. In February 591 surviving POWs (mostly pilots) came home to a joyous welcome.

After Nixon resigned in 1974, the US was legally unable and psychologically unwilling to fight in Indochina. The 1973 Peace Agreement, instead of ending a war. made continuation inevitable, for it allowed North Vietnam to keep troops in the South. The North, badly damaged by the bombings of 1972, recovered quickly and remained committed to the destruction of its rival. The main reason for the fall of South Vietnam in 1973 was the continued failure of the Saigon government to run an effective administration. Its weaknesses were compounded by exaggerated confidence that the U.S. would return if and when needed.[53]Although it was well-armed — its 2100 modern aircraft comprised the fourth largest air force in the world — the ARVN had never learned to fight large-scale operations against a conventional enemy.

Invasion and the fall of the south, 1975

Starting in March, 1975, Hanoi sent 18 divisions, with 300,000 of its 700,000, soldiers to invade the South again, in conventional fashion with marching armies spearheaded by 600 Russian-built tanks and 400 pieces of artillery, and using a conventional logistics structure. It had mobile air defenses including anti-aircraft artillery and possibly surface-to-air missiles. It had clear objectives, with political officers ready to deal with those that did not follow the plan.

The South Vietnamese military, however, had unclear goals, even on operational issues of when to trade territory for time. It had not learned to exercise command and control at the level of a national effort. The South's doctrine was called "light at the top, heavy at the bottom", meaning that it would resist lightly in the northern party of the country (I Corps), but stiffen resistance as the North extended. That was an attritional strategy, and the DRV had not broken under the much heavier attrition imposed by U.S. troops.

Its air force, however, performed poorly, and often abandoned its bases. [54][55]

The ARVN, with 1.1 million soldiers, still had a 2-1 advantage in combat soldiers and 3-1 in artillery, but it misused its resources badly. Some ARVN units fought well; most collapsed under the 16-division onslaught. The North Vietnamese regular army, the PAVN, began a full-scale offensive by seizing Phuoc Long Province in January, 1975. In March, 1975, they continued their offensive campaigns by conducting diversionary attacks in the north threatening Pleiku and then attacking the lightly defended South Vietnamese rear area.

The PAVN captured the Central Highlands and moved to the sea to divide the country. The PAVN blocked the South Vietnamese attempt to retreat from the Central Highlands and destroyed the ARVN II corps. Of the 314 M-41 and M-48 ARVN tanks assigned to the Highlands, only three made it through to the coast.[56]

President Thieu released written assurances, dated April 1973, from President Nixon that the U.S. would "react vigorously" if North Vietnam violated the truce agreement. But Nixon had resigned in August 1974 and his personal assurances were meaningless; After Nixon made the promises, Congress had prohibited the use of American forces in any combat role in Laos, Cambodia, and Vietnam without prior congressional approval. This was well known to the Saigon government. [57] President Gerald R. Ford tried to get new money for the South, but refused to consider any military action whatever.

About 140,000 refugees managed to flee the country, chiefly by boat. The PAVN then concentrated its combat power to attack the six ARVN divisions isolated in the north. After destroying these divisions, the PAVN launched its "Ho Chi Minh Campaign" that with little fighting seized Saigon on April 30, ending the war.[58]

No American military units had been involved until the final days, when Operation FREQUENT WIND was launched to evacuate Americans and 5600 senior Vietnamese government and military officials, and employees of the U.S. Vietnam was unified under Communist rule, as nearly a million refugees escaped by boat. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

References

- ↑ "Ha Noi celebrates Trung sisters 1,968th anniversary", Viet Nam News, 14 March 2008

- ↑ By the 1960s, Ho was primarily a symbol rather than an active leader. William J. Duiker, Ho Chi Minh: A Life (2000)

- ↑ Patti, Archimedes L. A (1980). Why Viet Nam?: Prelude to America's Albatross. University of California Press.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 , Chapter 6, "The Advisory Build-Up, 1961-1967," Section 1, pp. 408-457, The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 2

- ↑ Eckhardt, George S. (1991), Vietnam Studies: Command and Control 1950-1969, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army, pp. 68-71

- ↑ Pike, PAVN (1986)

- ↑ McMaster, H.R. (1997), Dereliction of Duty : Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, HarperCollins, ISBN 0060187956

- ↑ Sherman Kent for the Board of National Estimates, Memo 6-9-64 (for the Director of Central Intelligence): Would the Loss of South Vietnam and Laos precipitate a "Domino Effect"

- ↑ Collins, James Lawton, Jr., Chapter I: The Formative Years, 1950-1959, Vietnam Studies: The Development and Training of the South Vietnamese Army, 1950-1972, p. 64

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McNamara, Robert S. (20 July 1965), Notes for Memorandum from McNamara to Lyndon Johnson, "Recommendations of Additional Deployments to Vietnam,"

- ↑ Neuman, Stephanie G. (2001), Warfare and the Third World, Macmillan, p. 65-66

- ↑ Nagl, John A.; David H. Petraeus & James F. Amos et al. (December 2006), Field Manual 3-24 Counterinsurgency, US Department of the Army

- ↑ Mao, pp. 175-176

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Carland, John M. (2004), "Winning the Vietnam War: Westmoreland's Approach in Two Documents.", Journal of Military History" 68 (2): 553-574

- ↑ United States Marine Corps, Small Wars Manual (Reprint of 1940 Edition)

- ↑ The normal Marine term is "Marine Expeditionary Force", but "Expeditionary" had unfortunate colonialist connotations in Vietnam. Current USMC terminology is MEF.

- ↑ David M. Berman, "Civic Action," in Spencer Tucker, ed. Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War p. 73-74

- ↑ Tucker, ed., Encyclopedia of the Vietnam War (2000) pp 74-75, 276-77

- ↑ The History Channel (September 22, 1964), Goldwater attacks Johnson's Vietnam policy

- ↑ Defence Canada, The Use of Herbicides at CFB Gagetown from 1952 to Present Day

- ↑ Quoted in Clodfelter, p. 134

- ↑ Gibbs, James William (1986), The Perfect War: Technolwar in Vietnam, Atlantic Monthly Press, p. 170

- ↑ Lyndon B. Johnson (April 7, 1965), speech at Johns Hopkins University

- ↑ Lyndon B. Johnson (April 9, 1965), Task Force on Southeast Asian Economic and Social Development, National Security Action Memorandum 329

- ↑ Moore, Harold & Joseph Galloway (1992), We were soldiers once, and young: Ia Drang--The Battle That Changed The War In Vietnam, Random House

- ↑ Human Rights Watch, IV. Mine Warfare in Vietnam, IN ITS OWN WORDS: The U.S. Army and Antipersonnel Mines in the Korean and Vietnam Wars

- ↑ Eckhardt, pp. 64-68

- ↑ Thomas W. Scoville, Reorganizing for pacification support (1982) online edition

- ↑ Michal R. Belknap, The Vietnam War on Trial: The My Lai Massacre and the Court-Martial of Lieutenant Calley (2002). excerpt and text search; "Famous American Trials: The My Lai Courts-Martial 1970" online

- ↑ Shulimson, Jack, The Marine War: III MAF in Vietnam, 1965-1971, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center

- ↑ William C. Westmoreland, A Soldier Reports (1976), pp 164-66. Marine General Victor Krulak devotes ch 13 of his memoirs, First to Fight: An Inside View of the U.S. Marine Corps (1984) to the dispute. First to Fight pp 195-204 online; see also Douglas Kinnard, The War Managers American Generals Reflect on Vietnam (1991) discusses the tension on p 60-1, online

- ↑ John Prados and Ray W. Stubbe, Valley of Decision: The Siege of Khe Sanh (2004)

- ↑ Adams, Sam (1994), War of Numbers: An Intelligence Memoir, Steerforth Press

- ↑ Don Oberdorfer, Tet!: The Turning Point in the Vietnam War (2001) excerpt and text search; James H. Willbanks, The Tet Offensive: A Concise History (2006) excerpt and text search

- ↑ Elliott, The Vietnamese War: (2002) p. 1128

- ↑ Quoted in Robert D. Schulzinger, Time for War: The United States and Vietnam, 1941-1975 (1997) p. 261 online

- ↑ Tran Van Tra, Vietnam: History of the Bulwark B2 Theatre, Vol. 5: Concluding the 30-Years War (1982), pp. 35-36.

- ↑ Fiedler, David (Spring, 2003), "Project touchdown: how we paid the price for lack of communications security in Vietnam - A costly lesson", Army Communicator

- ↑ Center for Cryptologic History, National Security Agency (1993), PURPLE DRAGON: The Origin and Development of the United States OPSEC Program, vol. United States Cryptologic History, Series VI, The NSA Period, Volume 2

- ↑ Purple Dragon, p. 64

- ↑ Donaldson, Gary (1996), America at War Since 1945: Politics and Diplomacy in Korea, Vietnam, and the Gulf War, Greenwood Publishing Group, pp.120-124

- ↑ U.S. Department of State, Ending the Vietnam War, 1973-1975

- ↑ Australian War Memorial, Vietnam War 1962–75

- ↑ North Vietnamese Army’s 1972 Eastertide Offensive, September 1, 2006

- ↑ Wiest, Andrew (2006), Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: The Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, p. 124

- ↑ Dale Andradé, Trial by Fire: The 1972 Easter Offensive, America's Last Vietnam Battle (1995) 600pp.

- ↑ Lam Quang Thi, The Twenty-Five Year Century: A South Vietnamese General Remembers the Indochina War to the Fall of Saigon (2002), online edition.

- ↑ Wiest, p. 124

- ↑ Bruce Palmer, 25 Year War 122; Clodfelter 173; Davidson ch 24 and p. 738-59.