Vietnam War

Template:TOC-right While there are background factors that go back to the rebellion, against China, of the Trung Sisters in the first century C.E., limits need to be set on the scope of the Vietnam War. There are important background details variously dealing with the start of French colonization in Indochina, including the present countries of Vietnam and Laos, the expansion of Japan into Indochina and the U.S. economic embargoes as a result, and both the resistance to Japanese occupation and the Vichy French cooperation in ruling Indochina.

In the West, the term is usually considered to have begun somewhere in the mid-20th century. There were at least two periods of hot war, first the Vietnamese war of independence from the French, including guerilla resistance starting during the Second World War and ending in a 1954 Geneva treaty that partitioned the country into the Communist North (NVN) (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRV) and non-Communist South (SVN) (Republic of Vietnam, RVN). A referendum on reunification had been scheduled for 1956, but never took place.

While Communists had long had aims to control Vietnam, the specific decision to conquer the South was made, by the Northern leadership, in May 1959. The DRV had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy, involving military, diplomatic, covert action and psychological operations to achieve those objectives. Whether or not one agreed with those objectives, there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions. Its military first focused on guerilla and raid warfare in the south, simultaneously improving the air defensives of the north.

In contrast, the Southern governments from 1954 did not either have popular support or tight control over the populace. There was much jockeying for power as well as corruption.

Eventually, following the Maoist doctrine of protracted war, the final "Phase III" offensive was by conventional forces, the sort that the U.S. had tried to build a defense against when the threat was from guerrillas. T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon were not driven by ragged guerrillas.

Fighting gradually escalated from that point, with a considerable amount of covert Western action in Vietnam and Laos. After the Gulf of Tonkin incident, in which U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson claimed North Vietnamese naval vessels had attacked U.S. warships, open U.S. involvement began in 1964, and continued until 1972. After the U.S. withdrawal based on a treaty in Paris, the two halves were to be forcibly united, by DRV conventional invasion, in 1975.

This is not to suggest that 1945-1975 was the only conflict seen in the region. A Japanese invasion in 1941 triggered U.S. export embargoes to Japan, which affected the Japanese decision to attack Western countries in December 1941; see Vietnam, war, and the United States . Vietnamese nationalism goes back through the first French presence, but there was opposition to Chinese influence dating back to the Two Trung Sisters in the first century A.D.

From the perspective of some Vietnamese, the war was the military effort of the Communist Party of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh to defeat France (1946-54), and the same party, now in control of North Vietnam, to overthrow the government of South Vietnam (1958-75) and take control of the whole country, in the face of military intervention by the United States (1964-72). Others discuss the Viet Minh resistance, in the colonial period, to the French and Japanese, and the successful Communist-backed overthrow of the post-partition southern government, as separate wars. Unfortunately for naming convenience, there is a gap between the end of French rule and the start of partition in 1954, and the Northern decision to commit to controlling the South in 1959.

Without trying to name the wars, the key timeline events in modern history are:

- 1941: Japanese invasion of French Indochina

- 1945: End of World War II and return of Indochina to French authority

- 1954: End of French control and beginning of partition under the Geneva agreement; CIA covert operation started

- 1955: First overt U.S. advisors sent to the South

- 1959: North Vietnamese decision, in May 1959 to create the 559th (honoring the date) Transportation Group and begin infiltration of the South

- 1964: Gulf of Tonkin incident and start of U.S. combat involvement; U.S. advisors and support, as well as covert operations, had been in place for several years

- 1972: Withdrawal of last U.S. combat forces as a result of negotiation

- 1975: Overthrow of the Southern government by regular Northern troops, followed by reunification under a Communist government.

Tentative lists of subarticles to spin out (also see talk page)

- Vietnam, pre-colonial history

- Vietnam, French colonial period

- Vietnam War, World War II and immediate postwar

- Vietnam War, War of Vietnamese independence/Vietnam War, First Indochina War

- Vietnam War, Partition and decisions

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, buildup

- Vietnam, war, and the United States (emphasis on U.S. domestic politics)

- Vietnam War, Buddhist crisis and military coup of 1963

- Gulf of Tonkin incident (in progress)

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, Gulf of Tonkin and aftermath

- Operation ATTLEBORO, Battle of the Ia Drang, Battle of Bong Son, representative drafts at detailed level

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, air war in the North

- Operation Bolo, Operation ROLLING THUNDER, Operation LINEBACKER I, Operation LINEBACKER II, representative drafts at detailed level

- Vietnam War, Second Indochina War, U.S. withdrawal and endgame

To appreciate the complexity it is necessary to start with French colonialism in the 19th century, or, quite possibly, to go to Vietnamese drives for independence in the 1st century, with the Trung Sisters' revolt against the Chinese; the citation here mentions the 1968th anniversary of their actions.[1]

French Indochina Background

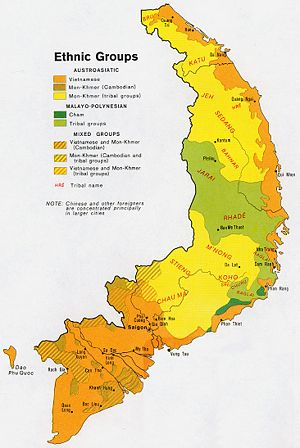

At the time of the French invasion, during the Second French Revolution with Louis Napoleon III as President, there were three parts of what is now Vietnam:

- Cochinchina in the south, including the Mekong Delta and what was variously named Gia Dinh, Saigon, and Ho Chi Minh City

- Annam in the center, but the mountainous Central Highlands, the home of the Montagnard peoples, considered itself autonomous

- Tonkin in the North, including the Red River Delta, Hanoi, and Haiphong.

In 1858, France invaded Vietnam, and the ruling Nguyen dynasty accepted protectorate status. Cambodia and Laos also came under French control. Danang, then called Tourane, was captured in late 1858 and Gia Dinh (Saigon and later Ho Chi Minh City) in early 1859. In both cases Vietnamese Christian support for the French, predicted by the missionaries, failed to materialize.

Vietnamese resistance and outbreaks of cholera and typhoid forced the French to abandon Tourane in early 1860. They returned in 1861, with 70 ships and 3,500 men to reinforce Gia Dinh and. In June 1862, Emperor Tu Duc, signed the Treaty of Saigon.

French naval forces under Admiral de la Grandiere, the governor of Cochinchina (as the French renamed Nam Bo), demanded and received a protectorate status for Cambodia, on the grounds that the Treaty of Saigon had made France heir to Vietnamese claims in Cambodia. In June 1867, he seized the last provinces of Cochinchina. The Siamese government, in July, agreed to the Cambodian protectorate in return for receiving the two Cambodian provinces of Angkor and Battambang, to Siam. Siam was never under French control.

With Cochinchina secured, French naval and mercantile interests turned to Tonkin (as the French referred to Bac Bo).

Indochina under the Third French Republic

With the collapse of Napoleon III, in 1870, as a result of the Franco-Prussian War, the French Third Republic formed, and lasted until the Nazi conquest in 1940. Most of the key actions that set the context into which the Empire of Japan moved into the region happened during this period, and in the immediate aftermath under the Vichy goverment.

Few Frenchmen permanently settled in Indochina. Below the top layer of imperial control, the civil service comprised French-speaking Catholic Vietnamese; a nominal "Emperor" resided in Hue, the traditional cultural capital in north central Indonesia.

Little industry developed and 80% of the population lived in villages of about 2000 population; they depended on rice growing. Most were nominally Buddhist; about 10% were Catholic. Minorities included the Chinese merchants who controlled most of the commerce, and Montagnard tribesmen in the thinly populated Central Highlands. Vietnam was a relatively peaceful colony; sporadic independence movements were quickly suppressed by the efficient French secret police.

Indochinese Communist Party forms

Ho Chi Minh (1890–1969) and fellow students founded the Indochinese Communist Party in Paris in 1929, but it was of marginal importance until World War II.[2] In 1940 and 1941 the Vichy regime yielded control of Vietnam to the Japanese, and Ho returned to lead an underground independence movement (which received a little assistance from the O.S.S., the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency CIA).[3]

World War II

Indochina, a French colony in the spheres of influence of Japan and China, was destined to be drawn into the Second World War both through European and Asian events. See Vietnam War, World War II and immediate postwar. From 1946 to 1948, the French reestablished control, but, in 1948, began to explore a provisional government. While there is no clear start to what ended in 1954, the more serious nationalist movement was clearly underway by 1948.

War of Indochinese independence

1948

Bao Dai participated in discussions about a provisional government, in which he might be an acceptable, if not ideal, head of state. The new government, established with Bao Dai as chief of state, was viewed critically by nationalists as well as communists. Most prominent nationalists, including Ngo Dinh Diem, refused positions in the government. Many went into voluntary exile. [4]

1949

Under French sponsorship in July, Bao Dai was named to head a provisional government, creating Vietnam from the Indochinese regions of Tonkin (north), Annam (central) and Cochinchina (south). Bao Dai said of it, "it is not a Bao Dai solution...but just a French solution." Among the many problems were that the non-Communist groups had too many conflicting ties, such as the VNQDD with the Chinese Kuomintang; the Constitutionalists, Cao Dai, Hoa Hao, and Binh Xuyen with France; the Dai Viet with Japan. Given this factionalism, the Viet Minh, accurately or not, enjoyed support as an uniquely Vietnamese faction.[5]

1950

A January 5, 1950 memorandum from the U.S. Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs described the U.S. policy assumption that [6] saw Vietnam as an autonomous state within the French Union, with Bao Dai, the former Emperor of Annam, as chief of state; U.S. policy was to strengthen him. The document said that Ho had been getting supplies from the Chinese Communists, but the extent was not known. A January 17 telegram from the Secretary of State said "Ho Chi Minh is not a patriotic nationalist but a Commie Party member with all the sinister implications in the relationship."[7]

U.S. diplomatic traffic in January speaks of unpopularity of Bao Dai, and how he could be strengthened. The designated charge d'affaires of the presumed U.S. mission to Vietnam recommended de jure recognition of Bao Dai, "de facto recognition of Bao Dai, in the popular meaning of the term, would mean that Bao Dai was in control of certain areas, and we recognized him to that extent only. The question would certainly arise, and not only in Communist propaganda, as to whether, in fact, Ho Chi Minh was in control of a larger area and a larger number of souls."[8]

France, on 29 January 1950, designated Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia as autonomous "Associated States" within the French Union. Voting in the lower house of Parliament was (396-193) with 181 of the opposing votes coming from French parliamentarians.[9] This was another example of the strength of the French Communist Party, which was a part of the U.S. geopolitical desire to support the Western-oriented parts of the French government. Shortly afterwards, the U.S. recognized them, which allowed direct military and economic assistance. The People's Republic of China responded by recognizing Ho's Democratic Republic of Vietnam, followed by Soviet recognition. Mao's revolutionary theory was praised in the Viet Minh press.

On 27 February the National Security Council issued memorandum 64 which dealt exclusively with United States policy toward Indochina. Its text included:

The neighboring countries of Thailand and Burma

could be expected to fall under Communist domination if Indochina were controlled by a Communist-dominated government. The balance of Southeast Asia would then be in grave hazard. Accordingly, the Departments of State and Defense should prepare as a matter of priority - [a] program of all practicable measures designed to protect U.S. interests in

Indochina. [10]

While the Joint Chiefs of Staff supported aid, they were conservative, saying "United States military aid not be granted unconditionally; rather, that it be carefully controlled and that the aid program be integrated with political and economic programs". Nevertheless, they saw little choice, assessing that Bao Dai's government could not survive without the 140,000 French soldiers in the field.

If the United States were now to insist upon independence for Vietnam and a phased French withdrawal from that country, this might improve the political situation. The French could be expected to interpose objections to, and certainly delays in, such a program. Conditions in Indochina, however, are unstable and the situation is apparently deteriorating rapidly so that the urgent need for at least an initial increment of military and economic aid is psychologically overriding.

They recommended an immediate USD $15,000,000 in aid, with additional funding granted in accordance with still-developing United States policy. [11]

President Truman, apparently without consulting any Members of Congress, approved the position on 24 April 1950 and the United States was officially committed to the Indochina war. "[12]

The Korean War began in June.

As another example of the pattern of the start of an offensive in late fall or winter, in October 1950, the Viet Minh started a campaign against French forts along the Chinese border. Large Viet Minh forces, in divisional strength, defeated isolated forts one by one, until the main base at Lang Son evacuated prematurely. French losses included 6,000 men and huge quantities of supplies. [13]

1951

While the Indochinese Communist Party had gone underground, officially dissolved in 1945 to obsecure the Viet Minh's communist base, it resurfaced as the Vietnam Workers' Party in February, at a meeting called the Second National Party Congress of the ICP. Ho was elected chairman and Truong Chinh as general secretary.

Given that the French had fallen back to a line north of Hanoi, the Viet Minh focused on Tonkin and consigned Cochinchina to a lower priority. Giap wanted to free the northern areas to allow easy logistics from China, and launched a major offensive, with newly formed units of divisional strength. Their goal was to be in Hanoi by Tet in mid-February.

Giap did not fully appreciate, while he had tactical initiative, that the French had fallen back to a defensible line, behind which they had significant mobility, as opposed to their situation at Dien Bien Phu in 1954. A new French commander, Marshal Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, had taken over the Indochina command in December 1950.

Battle of Vinh Yen

The first Viet Minh attacks, on January 13, went well. On the 14th, however, de Lattre took personal command, called for the airlift into his area of troops 1000 kilometers away, and gathered every aircraft — combat or trainer — that could carry napalm. At the Battle of Vinh Yen, Viet Minh forces, in the open and without anti-aircraft artillery, came under the heaviest air attacks that the French ever delivered. It cost them over 6,000 men. [14]

Fall quotes a Viet Minh officer,

However, all of a sudden, hell opens in front of my eyes. Hell comes in the form of large, egg-shaped containers dropping from the first plane, followed by other eggs from the second and third planes. Immense sheets of flmes, extending over hundreds of meters, it seems, strike terror into the ranks of my soldiers. This is napalm, the fire which falls from the skies.

As the oficer fell back, he urged a platoon commander to hold the French as long as possible while he reformed his troops. The junior officer's eyes were wide with terror "What is this? The atomic bomb?"

"No, it is napalm."[15] urging one of his platoon commanders to hold the advancing French infantry, while under air attack.

On 23 March, Giap tried again, striking at the Hanoi area from the east, across the Day River, towards Haiphong. This time, the French did not meet his open forces with air power, but with the fire from naval forces from the river. [16]

North Vietnamese political and organizational changes

These defeats caused low morale and desertions. Giap's political opponent in the Viet Minh, Truong Chinh, attempted to have him relieved, and Giap survived with humiliation. Giap had learned a valuable lesson.

The countryside was to encircle the towns, the mountains were to dominate the rice lands of the plains. [17]

He changed to leading the French on futile but costly chases. He encouraged them to defend static positions while he kept mobile, until, in 1954, he could fight a set-piece battle on his terms: Dien Bien Phu.

There were other political changes. While the military force continued, informally, to be called Viet Minh, the Viet Minh was formally absorbed into the "National Union of Viet Nam", or Lam Viet.[18]

De Lattre ordered an offensive to take Hoa Binh, with a first phase, Operation Tulipe, on November 10, 1951. General Salan had tactical control of the operation. By November 19, the force had taken Hoa Binh.

Giap did not stop his plans for an upcoming attack in the Red River delta, but counterattacked toward Hoa Binh, with the focus on Tu Vu. He took Tu Vu with heavy casualties on both sides.[19] Using it as a base, he began to reduce French pockets along the Black River, leading to Hoa Binh. The French fell back to the river, with uncomfortable similarities to the site-by-site movement against the norther fort line in October 1950. He also was able to block French river convoys moving to Hoa Binh.[20]

1952

On February 5, Salan decided to make a fighting withdrawal from Hoa Binh, on the grounds that the troops were needed in the defense of the Red River delta; the retreat was over by the 23rd.[21] There are suggestions he considered that a strong Delta defense had the chance of producing another Battle of Vinh Yen, where the French were able to mass air power on attacking troops in the open.

In April, Salan was named de Lattries' replacement.

Fall and Winter 1952

On October 17, 1952, the Communist forces opened a fall offensive with a three-division attack in the T'ai hill country of the North, centering on Nghia-Lo, which anchored the French static defense line in the area.

Senior French commanders, remembering the disastrous results to their border forts in 1950, decided to pull back, having one paratroop battalion jump in as a sacrificial rear guard. There had changes on the French side. Salan had held Na San, in October, trying to repeat the Vinh Yen victory with a strongpoint there, but the wiser Communists bypassed it. They took Nghia Loa in October and Dien Bien Phu in November; Dien Bien Phu had earlier been abandoned by the French. [22]

The paratroops held, taking heavy casualties, especially at Tu-Le Pass. The paratroops, in turn, asked a company of irregulars, at Muong-Chen, to hold while they escaped. 16 out of 84 of that unit survived. [23]

A deep counterattack, called Operation Lorraine, was prepared, using the largest French force in any one mission, approximately 30,000 men. Airborne and riverine units again surprised the enemy with their speed, as in Operation Lea in 1947.

After another parachute landing and link-up with tanks, in early November, French forces found, at Phu Duan, by no means a major depot new Soviet-built equipment. This included trucks, light through heavy mortars, and up-to-date individual weapons. Colonel Dodelier, commanding the operation, pointed out the strength of this secondary depot even after the Viet Minh had impressed local labor to remove all that cound be removed. He reflected "...how large the Viet Minh main depots in Ŷen Bay and Thai Nguyên must be. This certainly sheds a new light on the enemy's future offensive intentions."[24]

Giap had refused battle and continued to hold his Black River postions, and it was realized that Operation Lorraine had taken a position that was of no value. Salan ordered the Lorraine troops to begin a retreat, which began successfully but ran into major ambushes on the 17th. On November 23, Giap counterattacked against Na San, taking two outposts, but 308 Division was repulsed at Na San, with heavy losses. [25] By December 1, the French had destroyed Black River bridges and fallen back, with casualties equalling the strength of a battalion, yet not establishing — Na San was not it — the strongpoint against which the Communists would smash themselves, as they did at the Battle of Vinh Yen. They were to try once again to establish such a strongpoint, at a place called Dien Bien Phu.[26].

1953

In April, having completed their tours of duty, Salan and his key staff officers returned to France.[27] Henri Navarre, a protege of the senior solder of France, Marshal Alphonse Juin, replaced the mortally ill de Lattre on May 28. He had no Asian experience, and there were questions about his choices of staff and subordinates. [28]

Politics

The French established Bao Dai, who had called for, in the absence of a legislature, for major political leaders to join in a "National Congress" in Saigon. He thought it might strengthen his hand when he negotiated with the French. Bernard Fall, who attended, wrote: "That National Congress ... became a monumental free-for-all in which nationalists of all hues and shades concentrated on settling long-standing scores and in outbidding each other in extreme demands on the French and on the Vietnamese Government."[29]

French form a "fire brigade"

After the end of the Korean War, the French transferred their force to Indochina, the Bataillion de Corée, which had distinguished itself, to Indochina. On November 15, 1953, an reaction force, Groupe Mobile 100 (GM100), was created, with a core of the Korean veterans. [30]

The Dien Bien Phu strongpoint

Navarre, apparently in response to Thai pressure under the Franco-Thai treaty, decided to reoccupy Dien Bien Phu as a step to pacifying the Thai region of Indochina. Paratroopers jumped into Dien Bien Phu on November 20. Navarre also saw it as defending northern Laos, although General Catroux, the head of the subsequent French investigation into the disaster there, said it was quite limited in the area it could dominate.[31] It was harder to understand why the French thought it was a valid strongpoint. Navarre, and Pierre Koenig, a distinguished WWII commander, said that a group of U.S. experts had inspected the location and assured the French that plausible Russian anti-aircraft artillery could not interfere with its resupply by air, and that French artillery could defeat any Communist artillery in the surrounding hills. Catroux's investigation put special blame on the northern theater commander, Cogny, for not seriously testing the optimistic assumptions. [32]

Giap threatened Lai Chau, in Thailand, in December.[33]

1954

The North Vietnamese began their attack on Dien Bien Phu on March 12, with a force of 50,000 regular troops, 55,000 support troops, and 100,000 transport workers, versus 15,000 French. They had managed, quite beyond French expectation, to put well-protected artillery and air defenses into the surrounding high ground, making air resupply almost impossible. Brigadier General de Castries, commanding Dien Bien Phu, was a paratroop leader, skilled in the offensive but not an expert in dogged defense.

By March 15, the French realized that it could not be held, and appealed for U.S. intervention. Admiral Arthur Radford, Chairman of the Joint Staff, recommended, on five occasions, that the U.S. do so, but neither the other JCS members nor President Eisenhower supported him.

When Colonel Piroth, the fortress artillery commander, realized the situation in which his weapons were outclassed, he committed suicide on the night of March 16. When the French Defense Minister and Chief of Staff inspected on February 9, he had refused more equipment, saying he had more than he needed; the French had no idea how much the Vietnamese had emplaced. [34] While Chinese aid, literally carried 350 kilometers, reached 1,500 tons per month, the Viet Minh artillery closed the Dien Bien Phu airfield, the sole source of spply, on March 27.

Dien Bien Phu fell on May 7; the Geneva Conference began the next day.

GM100 dies

GM 100 had had some success in relieving An Khe in April. On June 24, however, GM100 was ambushed and destroyed.[35] There was a different outcome at almost the same spot, in 1965.

War's end

Officially, the war ended on July 20. Prisoner exchanges showed an unexpectedly high number of the French captives of the North Vietnamese had died in the prison camps, and that there had been, as in the Korean War, systematic pressure for conversion to the Communist cause.

1954 (post-French)-1956

- See also: Vietnam, war, and the United States

- See also: Vietnam War, Buddhist crisis and military coup of 1963

This period was begun by the military defeat of the French, with a Geneva meeting that partitioned Vietnam into North and South. Two provisions of the agreement never took place: a referendum on unification in 1956, and also banned foreign military support and intervention.

Also, after the end of French rule, Laos became independent, but with a struggle there among political factions, with neutralists heading the government and a strong Pathet Lao insurgency. Laos, also not to have had foreign military involvement according to the Geneva agreement, quickly had the beginnings of U.S. involvement as well as the continuing effects of North Vietnam sponsoring the Pathet Lao.

In a section titled "The Viet Minh Residue", the Pentagon Papers cited a study of 23 Viet Minh who had, according to U.S. analysts, gave consistent stories of being given stay-behind roles by the Viet Minh leadership going north. Some were given political roles, while others were told to await orders. "It is quite clear that even the activists were not instructed to organize units for guerrilla war, but rather to agitate politically for the promised Geneva elections, and the normalization of relations with the North. They drew much reassurance from the presence of the ICC, and up until mid-1956, most held on to the belief that the elections would take place. They were disappointed in two respects: not only were the promised elections not held, but the amnesty which had been assured by the Geneva Settlement was denied them, and they were hounded by the Anti-Communist campaign. After 1956, for the most part, they went "underground.""[36]

1954

Ngo Dinh Diem arrived in Saigon from France on 25 June 1954. and, with U.S. and French support, was named Premier of the State of Vietnam by Emperor Bao Dai, who had just won French assent to "treaties of independence and association" on 4 June.

The Saigon regime's major campaign that summer for inducing hundreds of thousands of Northerners to migrate to the South reflected a major political problem facing Diem-that of creating a popular base in the South. He was an Annamite, from Central Vietnam (although not the Central Highlands) in the South upon taking power. In seeking political support from Southerners, Diem was severely handicapped by the French postponement until after World War II of active preparations for Vietnamese self-government.

A major task was to create a viable alternative to the Vietminh in areas controlled by the French Army, especially the cities and towns, but also in pockets of the rural areas inhabited by people of the regional or "folk" religions, such as the Cao Dai. The base of this political alternative would be the small Vietnamese upper class which had been raised up by French colonial institutions. The French had already found, however, that this foundation was shaky; it lacked the coherence and strength of a well-established ruling class, and it was engaged in constant squabbling. [37]

Initial covert operations

The initial CIA team in Saigon was the Saigon Military Mission, headed by United States Air Force Colonel Edward Lansdale, who arrived on 1 June 1954. His diplomatic cover job was Assistant Air Attache. The broad mission for the team was to undertake paramilitary operations against the enemy and to wage political-psychological warfare. [38]

Working in close cooperation with the United States Information Agency (USIA), a new psychological warfare campaign was devised for the Vietnamese Army and for the government in Hanoi. Shortly after, a refresher course in combat psychological warfare was constructed and Vietnamese Army personnel were rushed through it.

The second SMM member, MAJ Lucien Conein, arrived on July 1. A paramilitary specialist, well-known to the French for his help with French-operated maquis in Tonkin against the Japanese in 1945, he was the one American guerrilla fighter who had not been a member of the Patti Mission. Conein was to have a continuing role, especially in the coup that overthrew Diem in November 1963. In August, Conein was sent to Hanoi, to begin forming a guerilla organization

A second paramilitary team for the south was formed, with Army LT Edward Williams doing double duty as the only experienced counter-espionage officer, working with revolutionary political groups.

External intelligence analysis

In August, a National Intelligence Estimate, produced by the CIA, predicted that the Communists, legitimized by the Geneva agreement, would take quick control of the North, and plan to take over all of Vietnam. The estimate went on that Diem's government was opposed both by Communist and non-Communist elements. Pro-French factions were seen as preparing to overthrow it, while Viet Minh would take a longer view. Under command of the north, Viet Minh individuals and small units will stay in the south and create an underground, discredit the government, and undermine French-Vietnamese relations.

Cite error: Invalid <ref> tag; invalid names, e.g. too many

US personnel dealing with the Government of Vietnam had difficulty in understanding the politics. The diplomats were not getting clear information in 1954 and early 1955, but the CIA station "had and has no mandate or mission to perform systematic intelligence and espionage in friendly countries, and so lacks the resources to gather and evaluate the large amounts of information required on political forces, corruption, connections, and so on." [38]

1955

By 31 January 1955, a paramilitary group had cached its supplies in Haiphong, having had them shipped by Civil Air Transport, a CIA proprietary airline belonging to the Directorate of Support

1956-1959 (up to North Vietnamese decision to invade)

As mentioned above, Viet Minh went underground in 1956, but there was no major decision until 1959. A 1964 interrogation report said "The period from the Armistice of 1954 until 1958 was the darkest time for the VC in South Vietnam. The political agitation policy proposed by the Communist Party could not be carried out due to the arrest of a number of party members by RVN authorities...In 1959 the party combined its political agitation with its military operations, and by the end of 1959 the combined operations were progressing smoothly." Note that this prisoner did not deny there were guerilla operations, but the document does not identify specific acts until 1957.

Under the French, the Montagnard tribes of the Central Highlands had had autonomy from the lowland colonial government. In 1956, these areas were absorbed into the Republic of Vietnam, and Diêm moved ethnic Vietnamese, as well as refugees from the North, into "land development centers" in the Central Highlands. Diem intended to assimilate the unwilling tribes, a point of ethnic resentment that was to become one of the many resentments against Diem.[39] These resentments both cost internal support, and certainly were exploited by the Communists.

1957

Guerilla attacks reported in 1957 included the killing of a group, not further identified, of 17 people in Chau-Doc in July, 1957. A District chief and his family were killed in September. In October, the clandestine radio of the "National Salvation Movement" began to broadcast support for armed opposition to Diem. Operations appeared to solidify in October, beyond what might have been small group actions:

In Washington, U.S. intelligence indicated that the "Viet Minh underground" had been directed to conduct additional attacks on U.S. personnel "whenever conditions are favorable." U.S. intelligence also noted a total of 30 armed "terrorist incidents initiated by Communist guerillas" in the last quarter of 1957, as well as a "large number" of incidents carried out by "Communist-lead [sic] Hoa Hao and Cao Dai dissident elements," and reported "at least" 75 civilians or civil officials assassinated or kidnapped in the same period.[40]

1958

Beginning with a plantation raid in January and a truck ambush in Febrary, there was steady guerilla ambushes and raids became more regular in 1958, and of serious concern to the GVN. This intensity level was consistent with Mao's Phase I, "the period of the enemy's strategic offensive and our strategic defensive." [41] Mao's use of "strategic defensive" refers to the guerilla force making its presence known and building its organization, but not attempting to engage military units. George Carver, the principal CIA analyst on Vietnam, said in a Foreign Affairs article,

A pattern of politically motivated terror began to emerge, directed against the representatives of the Saigon government and concentrated on the very bad and the very good. The former were liquidated to win favor with the peasantry; the latter because their effectiveness was a bar to the achievement of Communist objectives. The terror was directed not only against officials but against all whose operations were essential to the functioning of organized political society, school teachers, health workers, agricultural officials, etc. The scale and scope of this terrorist and insurrectionary activity mounted slowly and steadily. By the end of 1958 the participants in this incipient insurgency, whom Saigon quite accurately termed the "Viet Cong," constituted a serious threat to South Viet Nam's political stability"

Fall reported that the GVN lost almost 20% of its village chiefs through 1958.[40]

1959-1964 (up to Gulf of Tonkin incident)

To put the situation in a strategic perspective, remember that North and South Vietnam were artificial constructs of the 1954 Geneva agreements. While there had been several regions of Vietnam, when roughly a million northerners, of different religion and ethnicity than in the south, migrated into a population of four to five million, there were identity conflicts. Communism has been called a secular religion, and the North Vietnamese government officials responsible for psychological warfare and prisoner-of-war indoctrination were Military Proselytizing cadre. Communism, for its converts, was an organizing belief system that had no equivalent in the South. At best, the southern leadership intended to have a prosperous nation, although leaders were all too often focused on personal prosperity. Their Communist counterparts, however, had a mission of conversion by the sword — or the AK-47 assault rifle.

Between the 1954 Geneva accords and 1956, the two countries were still forming; the influence of major powers, especially France and the United States, and to a lesser extent China and the Soviet Union, were as much an influence as any internal matters. There is little question that in 1957-1958, there was a definite early guerilla movement against the Diem government, involving individual assassinations, expropriations, recruiting, shadow government, and other things characteristic of Mao's Phase I. The actual insurgents, however, were primarily native to the south or had been there for some time. While there was clearly communications and perhaps arms supply from the north, there is little evidence of any Northern units in the South, although organizers may well have infiltrated.

It is now confirmed that North Vietnam made a firm commitment, May 1959, to war in the South. Diem, well before that point, had constantly pushed a generic anticommunism, but how much of this was considered a real threat, and how much a nucleus around which he justified his controls, is less clear. Those controls, and the shutdown of most indigenous opposition by 1959, was clearly alienating the Diem government from significant parts of the Southern population, was massively mismanaging rural reforms and overemphasizing the power base in the cities, and might have had an independent rebellion. North Vietnam, however, clearly began to exploit that alienation. The U.S., however, did not recognize a significant threat, even with such information as intelligence on the formation of the logistics structure for infiltration. The presentation of hard evidence — communications intelligence about the organization building the Ho Chi Minh trail — Hanoi's involvement in the developing strife became evident. Not until 1960, however, did the U.S. recognize both Diem was in danger, that the Diem structure was inadequate to deal with the problems, and present the first "Counterinsurgency Plan for Vietnam (CIP)"

It can be established that there was endemic insurgency in South Vietnam throughout the period 1954-1960. It can also be established-but less surely- that the Diem regime alienated itself from one after another of those elements within Vietnam which might have offered it political support, and was grievously at fault in its rural programs. That these conditions engendered animosity toward the GVN seems almost certain, and they could have underwritten a major resistance movement even without North Vietnamese help.

There is little doubt that there was some kind of Viet Minh-derived "stay behind" organization betweeen 1954 and 1960, but it is unclear that they were directed to take over action until 1957 or later. Before that, they were unquestionably recruiting and building infrastructure, a basic first step in a Maoist protracted war mode.

While the visible guerilla incidents increased gradually, the key policy decisions by the North were made in 1959. Early in this period, there was a greater degree of conflict in Laos than in South Vietnam. U.S. combat involvement was, at first, greater in Laos, but the activity of advisors, and increasingly U.S. direct support to South Vietnamese soldiers, increased, under U.S. military authority, in late 1959 and early 1960. Communications intercepts in 1959, for example, confirmed the start of the Ho Chi Minh trail and other preparation for large-scale fighting.

Guerilla attacks increased in the early 1960s, at the same time as the new John F. Kennedy administration made Presidential decisions to increase its influence. Diem, as other powers were deciding their policies, was clearly facing disorganized attacks and internal political dissent. There were unquestioned conflicts between the government, dominated by minority Northern Catholics, and both the majority Buddhists and minorities such as the Montagnards, Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao. These conflicts were exploited, initially at the level of propaganda and recruiting, by stay-behind Viet Minh receiving orders from the North.

Republic of Vietnam strategy

Quite separate from its internal problems, South Vietnam faced an unusual military challenge. On the one hand, there was a threat of a conventional, cross-border strike from the North, reminiscent of the Korean War. In the fifties, the U.S. advisors focused on building a "mirror image" of the U.S. Army, designed to meet and defeat a conventional invasion. [36]

Diem (and his successors) were primarily interested in using the ARVN as a device to secure power, rather than as a tool to unify the nation and defeat its enemies. Province and District Chiefs in the rural areas were usually military officers, but reported to political leadership in Saigon rather than the military operational chain of command. The 1960 "Counterinsurgency Plan for Vietnam (CIP)" from the U.S. MAAG was a proposal to change what appeared to be a dysfunctional structure. [36] Further analysis showed the situation was not only jockeying for power, but also reflected that the province chief indeed had security authority that could conflict with that of tactical military operations in progress, but also had responsibility for the civil administration of the province. That civil administration function became more and more intertwined, starting in 1964 and with acceleration in 1966, of the "other war" of rural development.[42]

Communist strategy

The North had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy, involving military, diplomatic, covert action and psychological operations to achieve those objectives. Whether or not one agreed with those objectives, there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions. Its military first focused on guerilla and raid warfare in the south (i.e., Mao's "Phase I"), simultaneously improving the air defensives of the north. By the mid-sixties, they were operating in battalion and larger military formation that would remain in contact as long as the correlation of forces was to their advantage, and then retreat &mdash Mao's "Phase II".

Eventually, following the Maoist doctrine of protracted war, the final "Phase III" offensive was by conventional forces, the sort that the U.S. had tried to build a defense against when the threat was from guerrillas. T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon were not driven by ragged guerrillas.

In the Viet Cong, and in the North Vietnam regular army (PAVN), every unit had political officers, or Proselytizing Cadre. The Viet Cong had many unwilling draftees of its own; tens of thousands deserted to the government, which promised them protection. The Viet Cong executed deserters if it could, and threatened their families, all the while closely monitoring the ranks for any sign of defeatism or deviation from the party line.[43]

1959

Diem,in early 1959, felt under attack and broadly reacted against all forms of opposition, which was presented as a "Communist Denunciation Campaign", as well as some significant and unwelcome rural resettlement, the latter to be distinguished from land reform.

Increased activity in Laos

In May, the North Vietnamese made the commitment to an armed overthrow of the South, creating the 559th Transportation Group, named after the creation date, to operate the land route that became known as the Ho Chi Minh Trail. Additional transportation groups were created for maritime supply to the South: Group 759 ran sea-based operations, while Group 959 supplied the Pathet Lao by land routes. [44]. Group 959 also provided secure communications to the Pathet Lao. [45]

The Pathet Lao both were operating against the Laotian government, but also working with NVA Group 959 to supply the southern insurgency; much of the original Trail was in Laos, first supplying the Pathet Lao. Nevertheless. the Laotian government did not want it known that it was being assisted by the US in the Laotian Civil War against the Pathet Lao. U.S. military assistance could also be considered a violation of the Geneva agreement, although North Vietnam, and its suppliers, were equally in violation.

In July, CIA sent a unit from United States Army Special Forces, who arrived on CIA proprietary airline Air America, wearing civilian clothes and having no obvious US connection. These soldiers led Meo and Hmong tribesmen against Communist forces. The covert program was called Operation Hotfoot. At the US Embassy, BG John Heintges was called the head of the "Program Evaluation Office."[46]

CIA directed Air America, in August 1959, to train two helicopter pilots. Originally, this was believed to be a short-term requirement, but "this would be the beginning of a major rotary-wing operation in Laos.

Escalation and respons in the South

Cause and effect are unclear, but it is also accurate that the individual and small group actions, by the latter part of 1959, included raids by irregulars in battalion strength.

Vietnam was a significant part of the agenda of the U.S. Pacific commanders' conference in April. Lieutenant General Samuel T. Williams, chief of the U.S. Militiary Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam,[47] cited the key concerns as:

- absence of a national plan for control of the situation

- no rotation of military units in the field

- the need for a central surveillance plan

- the proliferation of Ranger-type counterinsurgency units without central direction and without a civil-military contetx

- inadequate intelligence

- inadequate military communications

- lack of centralized direction of the war effort.

LTG Williams pointed to the dual chain of command of the ARVN, as distinct from the Civil Guard. The latter was commanded by the Department of the Interior, and controlled by province and district chiefs. This structure let the U.S. Operations Mission (USOM, the contemporary term for non-military foreign aid from the Agency for International Development financially aid the Guard, they were so dispersed that there could be no systematic advice, much less to the combination of Guard and Army. [48]

Under the authority of the commander of United States Pacific Command, it was ordered that Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam (MAAG-V) assign advisors to the infantry regiment and special troops regiment level, who were not to participate directly in combat. advisers be provided down to infantry regiment and to artillery, armored, and separate Marine battalion level. This move would enable advisers to give on-the-spot advice and effectively assess the end result of the advisory effort. He also requested United States Army Special Forces (SF) mobile training teams (MTT) to assist in training ARVN units in counterinsurgency.

Structural barriers to effectiveness of RVN forces

When the MAAG was instructed to improve the effectiveness of the RVN, the most fundamental problem was that the Diem government had organized the military and paramilitary forces not for effectiveness, but for political control and patronage. The most obvious manifestation of Diem's goal was that there were two parallel organizations, the regular military under the Department of National Defense and the local defense forces under the Ministry of the Interior. Diem was the only person who could give orders to both.

Command and control

President Diem appointed the Secretary of State for National Defense and the Minister of the Interior. The Defense Secretary directed of General Staff chief and several special sub-departments. The General staff chief, in turn, commanded the Joint General Staff (JGS), which was both the top-level staff and the top of the military chain of command.

There were problems with the military structure, even before considering the paramilitary forces under the Interior Ministry. The JGS itself had conflicting components with no clear authority. For example, support for the Air Force came both from a Director of Air Technical Service and a Deputy Chief of Air Staff for Matériel. The Director was, in principle, under the Chief of Staff., but actually reported to the Director General of Administration, Budget, and Comptroller for fiscal matters).

Combat units also had conflicting chains of command. A division commander might receive orders both from the corps-level tactical commander who actually carried out the operational art role of corps commanders in most militaries, but also from the regional commander of the home base of the division — even if the division was operating in another area. The chiefs of branches of service (e.g., infantry, artillery), who in most armies were responsible only for preparation and training of personnel of their branch, and orders only before they were deployed, would give direct operational orders to units in the field.

Diem himself, who had no significant military background, could be the worst micromanager of all, getting on a radio in the garden of the Presidential Palace, and issuing orders to regiments, bypassing the Department of National Defense, Joint General Staff, operational commanders, and division commanders. In fairness to Diem, Lyndon Johnson and his political advisors would do detailed air operations planning for attacks in the North, with no input from experienced air officers. Henry Kissinger, in the Mayaguez incident, got onto the tactical radio net and confused the local commanders with German-accented and obscure commands. Of course, Johnson and Kissinger had more military experience than Diem; Johnson had briefly worn a Navy uniform on an inspection trip before returning to Congress, and Kissinger lectured on politics at the end of WWII and the start of the Occupation, with a high status but an actual rank of Private, United States Army.

"The Department of National Defense and most of the central organizations and the ministerial services were located in downtown Saigon, while the General Staff (less air and navy elements) was inefficiently located in a series of company-size troop barracks on the edge of the city. The chief of the General Staff was thus removed several miles from the Department of National Defense. The navy and air staffs were also separately located in downtown Saigon. With such a physical layout, staff action and decision-making unduly delayed on even the simplest of matters.

"The over-all ministerial structure described above was originally set up by the French and slightly modified by presidential decree on 3 October 1957. Military Assistance Advisory Group, Vietnam, had proposed a different command structure which would have placed the ministry and the "general staff" in closer proximity both physically and in command relationship. But the proposal was not accepted by President Diem, perhaps because he wished to continue to maintain a division of power and prevent any one individual--other than himself--from having too much authority. Thus, during the period in question, the existing system was accepted by the advisory group which, in turn, served as lubrication for its more delicate components.

The chain of command of both the Civil Guard and Self-Defense Corps, went from the Ministry of the Interior to the province chiefs, district chiefs, and village councils. Even though the province chiefs and district chiefs were often military officers, ARVN units operating in a province or district could not give orders to these units. Instead, they had to pass a request through military channels to the Ministry of Defense in Saigon. If the officials there agreed, they would convey the request to their counterparts in the Ministry of the Interior, who would then send orders down its chain of command to the local units.

Regular military

- Three corps headquarters and a special military district:[49]

- Seven divisions of 10,450 men

- three infantry regiments

- artillery battalion

- mortar battalion

- engineer battalion

- company-size support elements

- Airborne group of five battalion groups

- four armored cavalry "regiments" (approximately the equivalent of a U.S. Army cavalry squadron)

- one squadron (U.S. troop) of M24 light tanks

- two squadrons of M8 self-propelled 75-mm. howitzers

- Eight independent artillery battalions with U.S. 105-mm, and 155-mm. pieces.

Local defense forces

Created by presidential decree in April 1955, and originally under the direct control of President Diem, with control passed to the Ministry of the Interior in September 1958, the Civil Guard was made up of wartime paramilitary veterans. Its major duty was to relieve the ARVN of static security missions, freeing it for mobile operations, with additional responsibility for local intelligence collection and counterintelligence. in 1956, had 68,000 men organized into rganized into companies and platoons, the Civil Guard was represented by two to eight companies in each province. It had a centrally controlled reserve of eight mobile battalions of 500 men each, .

Operating on a local basis since 1955 and formally created in 1956, the Self-Defense corps was a village-level police organization, for protection against intimidation and subversion. It put units of 4-10 men into villages of 1,000 or more residents. In 1956, it had 48,000 non-uniformed troops armed with French weapons. The Self-Defense Corps, like the Civil Guard, was established to free regular forces from internal security duties by providing a police organization at village level to protect the population from subversion and intimidation. Units of four to ten men each were organized in villages of 1,000 or more inhabitants.

The Civil Guard and the Self-Defense Corps were poorly trained and ill-equipped to perform their missions, and by 1959 their numbers had declined to about 46,000 and 40,000, respectively.

1960

As mentioned in the introduction to this section, the U.S. was urging the RVN to revise its parallel province/district command and military operations command structure; the Counterinsurgency Plan (CIP) was the first of several such proposals.

Laotian operations

After the 180 day assignment of the Special Forces personnel in Laos, the name changed to Operation White Star, under COL Arthur "Bull" Simons.

Beginning of Phase II raids

On 25 January 1960, a Communist force of 300 to 500 men escalated with a direct raid on an ARVN base at Tay Ninh, killing 23 soldiers and taking large quantities of munitions. Four days later, a guerilla group seized a town for several hours, and stole cash from a French citizen. These were still in the first Maoist stage, as raids rather than hit-and-run battles. Still, larger guerilla forces broke lines of communications within areas of South Vietnam.

There was uncertainty, expressed by Bernard Fall and in a March U.S. intelligence assessment, that there were distinct plans to conduct larger-scale operations "under the flag of the People's Liberation Movement," which was identified as "red, with a blue star." It was uncertain if their intent was to continue to build bases in the Mekong Delta, or to isolate Saigon. The Pentagon Papers stated the guerillas were establishing three options, of which they could exercise one or more;

- incite an ARVN revolt

- set up a popular front government in the lower Delta

- force the GVN into such repressive countermeasures that popular uprisings will follow.

Formation of the NLF

In December, the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF) formally declared its existence, although it did not hold its first full congress until 1962.

The NLF platform recognized some of the internal stresses under the Diem government, and put language in its platform to create autonomous regions in minority areas and for the abolition of the "U.S.-Diêm clique's present policy of ill-treatment and forced assimilation of the minority nationalities". [39] Such zones, with a sense of identity although certainly not political autonomy, did exist in the North. In the early 60s, NLF political organizers went to the Montagnard ares in the Central Highlands, and worked both to increase alienation from the GVN and directly recruit supporters.

1961

Not surprisingly, with a change in U.S. administration, there were changes in policy, and also continuations of some existing activities. There were changes in outlook. Kennedy was unquestionably anti-Communist, but his administration did not treat it as the existential crusade that Eisenhower's secretary of state, John Foster Dulles, had waged.

Defense Secretary Robert S. McNamara (in office 1961-68) told President John F. Kennedy (in office 1961-63) in 1961 it was "absurd to think that a nation of 20 million people can be subverted by 15-20 thousand active guerrillas if the government and the people of that country do not wish to be subverted."[50] McNamara, a manufacturing executive and expert in statistical management, had no background in guerilla warfare or other than Western culture, and rejected advice from area specialists and military officers. He preferred to consult with his personal team, often called the "Whiz Kids"; his key foreign policy advisor was a law professor, John McNaughton, while economist Alain Enthoven was perhaps his closest colleague.

Still trying to resolve the problems of GVN conflicting command, a new reorganizational proposal, the "Geographically Phased Plan". The goal was to have a coherent national plan, which was, in 1962, to be expressed as the Strategic Hamlet Program.

Kennedy pushes for covert operations against the North

On January 28, 1961, shortly after his inauguration, John F. Kennedy told a National Security Council meeting that he wanted covert operations launched against North Vietnam, in retaliation for their equivalent actions in the South.[51]. This is not argue that this was an inappropriate decision, but the existence of covert operations against the North, has to be understood in analyzing later events, especially the Gulf of Tonkin incident.

Even earlier, he issued National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 2, directing the military to prepare counterinsurgency forces, although not yet targeting the North. [52]

Kennedy discovered that little had progressed by mid-March, and issued National Security Action Memorandum (NSAM) 28, ordering the CIA respond to his desire to launch guerilla operations against the North. Herb Weisshart, deputy chief of the Saigon CIA station, observed the actual CIA action plan was "very modest". Given the Presidential priority, Weisshart said it was modest because William Colby, then Saigon station chief, said it would consume too many resources needed in the South. He further directed, in April, a presidential task force to draft a "Program of Action for Vietnam".

In April, the Bay of Pigs invasion of Cuba, under the CIA, had failed, and Kennedy lost confidence in the CIA's paramilitary opeations. Kennedy himself had some responsibility for largely cutting the Joint Chiefs of Staff out of operational planning. The JCS believed the operation was ill-advised, but, if it was to be done, American air support was absolutely essential. Kennedy, however, had made a number of changes to create plausible deniability, only allowing limited air strikes by CIA-sponsored pilots acting as Cuban dissidents. After it was learned that the main strike had left behind a few jet aircraft, he refused a followup strike; those aircraft savaged the poorly organized amphibious ships and their propeller-driven air support.

The U.S. Air Force, however, responded to NSAM 2 by creating, on April 14, 1961, the 4400th Combat Crew Training Squadron (CCTS), code named “Jungle Jim.” The unit, of about 350 men, had 16 C-47 transports, eight B-26 bombers, and eight T-28 trainers (equipped for ground attack), wih an official of training indigenous air forces in counterinsurgency and conduct air operations. A volunteer unit, they would deploy in October, to begin FARM GATE missions.

The task force reported back in May, with a glum assessment of the situation in the South, and a wide-ranging but general plan of action, which becam NSAM 52. In June, Kennedy issued a set of NSAMs transferring paramilitary operations to the Department of Defense. [53]. These transfers of responsibility should be considered not only in respect to the specific operations against the North, but in the level of covert military operation in the South in the upcoming months. This transfer also cut the experienced MG Edward Lansdale out of the process, as while he was an U.S. Air Force officer, the military saw him as belonging to CIA.

Intelligence support

Also in May, the first U.S. signals intelligence unit, from the Army Security Agency under National Security Agency control, the unit, operating under the cover name of the 3rd Radio Research Unit. Organizationally, it provided support to MAAG-V, and trained ARVN personnel, the latter within security constraints. The general policy, throughout the war, was that ARVN intelligence personnel were not given access above the collateral SECRET (i.e., with no access to material with the additional special restrictions of "code word" communications intelligence (CCO or SI)".

Their principal initial responsibility was direction finding of Viet Cong radio transmitters, which they started doing from vehicles equipped with sensors. On December 22, 1961, an Army Security Agency soldier, SP4 James T. Davis, was killed in an ambush, the first American soldier to die in Vietnam.

Covert U.S. air support enters the South

More U.S. personnel, officially designated as advisors, arrived in the South and took an increasingly active, although covert, role. In October, a U.S. Air Force special operations squadron,, part of the 4400th CCTS deployed to SVN, officially in a role of advising and training. The aircraft were painted in South Vietnamese colors, and the aircrew wore uniforms without insignia and without U.S. ID. Sending military forces to South Vietnam was a violation of the Geneva Accords of 1954, and the U.S. wanted plausible deniability.

The deployment package consisted of 155 airmen, eight T-28s, and four modified and redesignated SC-47s and subsequently received B-26s. U.S. personnel flew combat as long as a VNAF person was aboard. FARMGATE stayed covert until after the Gulf of Tonkin incident.[52]

Building the South Vietnamese Civil Irregular Defense Groups

Under the operational control of the Central Intelligence Agency,[54] initial U.S. Army Special Forces involvement came in October, with the Rhade. [55] The Civilian Irregular Defense Groups (CIDG), were under Central Intelligence Agency operational control until July 1, 1963, when MACV took control. [56]. Army documents refer to control by "CAS Saigon", a cover name for the CIA station. According to Kelly, the SF and CIA rationale for establishing the CIDG program with the Montagnards was that minority participation would broaden the GVN counterinsurgency program, but, more critically,

the Montagnards and other minority groups were prime targets for Communist propaganda, partly because of their dissatisfaction with the Vietnamese government, and it was important to prevent the Viet Cong from recruiting them and taking complete control of their large and strategic land holdings.[57]

It was in mid-November when Kennedy decided to take on operational as well as advisory roles. Under U.S. a Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG), such as the senior U.S. military organization in Vietnam, is a support and advisory organization. A Military Assistance Command (MAC) is designed to carry out MAAG duties, but also to command combat troops. [58]. There was considerable discussion about the reporting structure of this of the organization: a separate theater reporting to the National Command Authority or part of United States Pacific Command.

First Honolulu Conference

After meetings in Vietnam by GEN Taylor, the Secretaries of State and Defense issued a set of recommendations, on November 11. [59] Kenbnedy accepted all except the use of large U.S. combat forces.

McNamara held the first Honolulu Conference, at United States Pacific Command headquarters, with the Vietnam commanders present. He addressed short-term possibilities, urging concentration on stabilizing one province: "I'll guarantee it (the money and equipment) provided you have a plan based on one province. Take one place, sweep it and hold it in a plan." Or, put another way, let us demonstrate that in some place, in some way, we can achieve demonstrable gains. [36]

First U.S. direct support to an ARVN combat operation

On 11 December 1961 the United States aircraft carrier USNS Card docked in downtown Saigon with 82 U. S. Army H-21 helicopters and 400 men. organized into two Transportation Companies (Light Helicopter); Army aviation had not yet become a separate branch.

Twelve days later these helicopters were committed into the first airmobile combat action in Vietnam, Operation CHOPPER. It was the first time U.S. forces directly and overtly supported ARVN units in combat, although the American forces did not directly attack the guerillas.Approximately 1,000 Vietnamese paratroopers were airlifted into a suspected Viet Cong headquarters complex about ten miles west of the Vietnamese capital, achieving tactical surprise and capturing a radio station. [60]

1962

From the U.S. perspective, the Strategic Hamlet Program was the consensus approach to pacifying the countryside.[36] There was a sense, however, that this was simply not a high priority for Diem, who considered his power base to be in the cities. The Communists, willing to fill a vacuum, became more and more active in rural areas where the GVN was invisible, irrelevant, or actively a hindrance.

Unfortunately, the Strategic Hamlet Program meant different things to various South Vietnamese and American groups. It was not simply building the hamlet that would carry out a strategy, but the context in which they were built. There was a good deal of agreement that it had to be phased:

- Clearing enemy forces, the responsibility of the regular ARVN, coupled with some level of "holding"

- Maintaining security, by various civil guard organizations and regional reaction forces

- Hamlet self-defense capability, enabling economic development and strengthened local government

The U.S. political leadership focused on the latter part of the program. The U.S. military somewhat regretfully focused on the first, with concern that the ARVN would bog down in "holding", when the ARVN was needed to take the initiative away from the enemy, so the VC were defending, not attacking. Both, however, did not see long-term success without reforms in the Diem government. Diem, however, was more concerned with preserving than reforming his government. American appeals to form a "partnership" may not have been seriously considered. See Operation SUNRISE for a representative early attempt to create a hamlet (March 1962).

Absentee landlords formed a significant part of Diem's power base, in a quasi-feudal system that contained resentments the NLF could exploit. Much of Vietnamese rural culture was tied to the ancestral lands where they were located, yet the villagers did not own their fields and homes.[61] Gibson quotes a landlord interviewed by Samson:

In the past, the relationship between the landlord and his tenants was paternalistic. The landlord considered the tenant as an inferior member of his extended family. When the tenant's father dieed, it was the duty of the landlord to give money to the tenant for the funeral; if his wife was pregnamt, the landlord gave mone for the birth; if he was in financial ruin, the landlord gave assistance; therefore, the tenant had to behave as an inferior member of the extended family. The landlord enjoyed great prestige vis-a-vis the tenant. [62]

During this period of paternalism, the landlord also received 40 to 60 percent of the tenants' crops as rent. When the Viet Minh fought the French, they also fought an economic war, and drove large landowners into the cities, or variously lowered or ended rent payments. According to Gibson, when Diem's ARVN forces established security, they put landlords back in control, often demanding back rent. [63]

Separarately from the land reform and economic issues, the Government of Vietnam were unable to provide security for the villages. The Diem government response was to create defensible "strategic hamlets" and forcibly move the villagers to them. The strategic hamlet might have government-appointed or military leaders; the villagers' locally chosen leadership was destroyed. The tombs of ancestors was abandoned, in a culture where it was proper to show ancestral respect.

Special Forces operations

In 1962, the U.S. Military Command–Vietnam (MACV) established Army Special Forces camps near villages. The Americans wanted a military presence there to block the infiltration of enemy forces from Laos, to provide a base for launching patrols into Laos to monitor the Ho Chi Minh Trail, and to serve as a western anchor for defense along the DMZ.[64] These defended villages were not part of the Strategic Hamlet Program, but did provide examples that were relevant.

U.S. ground command structure established

U.S. command structures continued to emerge. On February 8, Paul D. Harkins, then Deputy Commanding General, U.S. Army Pacific, under Pacific Command, was promoted to general and assigned to command the new Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MAC-V).

Military Assistance Command-Thailand was created on May 15, 1962, but reported to Harkins at MAC-V. In a departure from usual practice, the MAAG was retained as an organization subordinate to MAC-V, rather than being absorbed into it. The MAAG continued to command U.S. advisors and direct support to the ARVN. At first, MAC-V delegated control of U.S. combat units to the MAAG. While it was not an immediate concern, MAC-V never controlled all the Air Force and Navy units that would operate in Vietnam, but from outside its borders. These remained under the control of Pacific Command, or, in some cases, the Strategic Air Command.

No regular ARVN units were under the command of U.S. military commanders, although there were exceptions for irregular units under Special Forces. Indeed, there could be situations where, in a joint operation, U.S. combat troops were under a U.S. commander, while the ARVN units were under an ARVN officer with a U.S. advisor. Relationships in particular operations often were more a matter of personalities and politics rather than ideal command. U.S troops also did not report to ARVN officers; while many RVN officers had their post through political connections, others would have been outstanding commanders in any army.

At the same time, the U.S. was beginning to explore withdrawing forces. [65]

Intelligence support refines

The USMC 1st Composite Radio Company deployed, on January 2, 1962, to Pleiku, South Vietnam as Detachment One. After Davis' death in December, it became obvious to the Army Security Agency that thick jungle made tactical ground collection exceptionally dangerous, and direction-finding moved principally to aircraft platforms.[66] See first-generation Army tactical SIGINT.

Additional allied support

In addition to the U.S. advisers, in August 1962, 30 Australian Army advisers was sent to Vietnam to operate within the United States military advisory system. As with most American advisors, their initial orders were to train, but not go on operations.[67]

1963

South Vietnamese forces, with U.S. advisors, took severe defeats at the Battle of Ap Bac in January,[68]. This has been considered the trigger for an increasingly skeptical, although small, American press corps in Vietnam. and the Battle of Go Cong in September. Ap Bac was of particular political sensitivity, as John Paul Vann, a highly visible American officer, was the advisor, and the U.S. press took note of what he considered to be ARVN shortcomings.

While the Buddhist crisis and military coup that ended with the killing of Diem was an obvious major event, it was by no means the only event of the year. In keeping with the President's expressed desires, covert operations against the North were escalated. Of course, the assassination of Kennedy himself brought Lyndon Baines Johnson, with a different philosophy toward the war. Kennedy was an activist, but had a sense of unconventional warfare and geopolitics, and, as is seen in the documentary record, discussed policy development with a wide range of advisors, specifically including military leaders. Johnson tended to view the situation from the standpoint of U.S. domestic policy, and, probably from his immensely successful experience as a deal-maker in the U.S. Senate, believed that everything was negotiable. When the North Vietnamese did not respond as Johnson wanted, he took it personally, and may have made some judgments based on his emotional responses to Ho. He also spoke with a much smaller advisory circle than Kennedy, and excluded active military officers. [69]

Intelligence support

On September 17, 1963, Detachment One, 1st Composite Radio Company, U.S. Marines, was redesignated as 1st Radio Company, Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii, but still put detachments into Vietnam.

May 1963 Honolulu conference; covert warfare a major issue

At the May 6 Honolulu conference, the decision was made to increase, as the President had been pushing, covert operations against the North. A detailed plan for covert operations, Pacific Command Operations Plan 34A (OPPLAN 34A) went to GEN Taylor, now Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, did not approve it until September 9. Shultz suggests the delay had three aspects:

- Washington was preoccupied with the Buddhist crisis

- MACV had no established covert operations force, so even if he approved a plan, there was no one to execute it

- Taylor, although a distinguished Airborne (paratroopers once being believed special operators) officer, disagreed with Kennedy's emphasis on covert operations, did not have the appropriate resources in the Department of Defense, and he did not believe it was a proper job for soldiers.

- Diem, fighting for survival, was not interested

It is unclear if Taylor did not believe covert operations should not be attempted at all, or if he regarded it as a CIA mission. If the latter, Kennedy would have been unlikely to support him, given the President's loss of confidence after the Bay of Pigs fiasco. [70]

After two assassinations

Kennedy and Diem both died in November 1963. Since Diem was killed by a military junta, there was no immediate successor, but Lyndon Johnson became the new President of the United States. Johnson was far more focused on domestic politics than the international activist, Kennedy. Some of the Kennedy team left quickly, while others, sometimes surprisingly given extremely different personalities, stayed on; the formal and logical Robert McNamara quickly bonded with the emotional and deal-making Johnson.

McNamara was insistent that a rational enemy would not accept the massive casualties that indeed were inflicted on the Communists. The enemy, however, was willing to accept those casualties. [71] McNamara was insistent that the enemy would comply with his concepts of cost-effectiveness, of which Ho and Giap were unaware. They were, however, quite familiar with attritional strategies.[72] While they were not politically Maoist, they were also well versed in Mao's concepts of protracted war (see insurgency).[41]

Johnson approval of covert operations

OPPLAN 34A was finalized around December 20, under joint MACV-CIA leadership; the subsequent MACV-SOG organization had not yet been created. There were five broad categories, to be planned in three periods of 4 months each,over a year:[73]

- Clandestine human-source and signals intelligence collection from locations in the north

- Psychological operations against the north to increase tension and division; Colby had already started such operations

- Paramilitary operations,such as raids and sabotage against facilities that were significant to the admittedly weak economy, and stronger security, of North Vietnam

- Encouraging the development of an underground resistance movement

- Selected raids as well as reconnaissance to direct air strikes, with more of a tactical goal than the economic and security actions of category 3

Lyndon Johnson agreed with the idea, but was cautious. He created an interdepartmental review committee, under MG Victor Krulak, on December 21, to select the least risky operations on December 21, which delivered a report on January 2, 1964, for the first operational phase to begin on February 1. It was hardly an expression of the motto of David Stirling, founder of Britain's legendary Special Air Service: "Who dares, wins."

North Vietnam decides on escalation

In December 1963, a decisive meeting of the Communist Party Central Committee in Hanoi set basic policy. Le Duan (1907-86) was in full control; Ho Chi Minh had become a figurehead. [74] COL Bui Tin led a reconnaissance mission of specialists reporting directly to the Politburo, who said, in an 1981 interview with Stanley Karnow, that he saw the only choice was escalation including the use of conventional troops, capitalizing on the unrest and inefficiency from the series of coups in the South. The Politburo ordered infrastructure improvements to start in 1964.[75]

1964 (before Gulf of Tonkin Incident)