Stress and appetite

For the course duration, the article is closed to outside editing. Of course you can always leave comments on the discussion page. The anticipated date of course completion is 01 February 2011. One month after that date at the latest, this notice shall be removed. Besides, many other Citizendium articles welcome your collaboration! |

Begin your article with a brief overview of the scope of the article. Include the article name in bold in the first sentence.

Introduction to Stress and the HPA axis

What is Stress?

Differences between emotional/inflammatory?

Stress is an emotional and physiological response phenomenon which almost all of us have experienced at some point or another. The stereotypic stress response is initiated when the body perceives a stimuli to be threatening or very intense. This activates the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis directly, resulting in heightened vigilance, enhanced cognition and arousal of the autonomic system (Habib KE et al, 2001). These physiological responses help to protect both the body and the brain from any harmful effects of the stress stimuli, although chronic stress states have been shown to have detrimental effects on the brain (Wood GE et al, 2004).

The activation of the HPA axis plays a major role in moderating the stress response. This triggers a cascade which ultimately leads to the secretion of the glucocorticoid cortisol from the adrenal cortex. Cortisol acts on the cytoplasmic receptors of many cells to initiate gene transcription and eventually protein synthesis. Cortisol also results in an increase in calcium influx via voltage-gated ion channels, although the exact mechanism of this remains unknown. While a moderate increase in intracellular calcium increases a cell's excitability, calcium overloading lead to excitotoxicity and neuron death. McEwen/ Sapolsky eveidence...

The HPA axis

The HPA axis is comprised of the Hypothalamus, the Pituitary and the Adrenal gland. The hypothalamus acts as the control centre for most of the hormonal systems in the body. In response to a stressor, be it psychological or physiological, corticotropin-releasing Factor (CRF) is secreted. CRF is a polypeptide hormone which is synthesised in the paraventricular nucleus (PVN) and released from the median eminance. CRF induces corticotropes at the anterior pituitary to secrete adrenocorticotrophic hormone (ACTH). In turn, ACTH acts on the adrenal glands on the kidneys to stimulate the release of adrenal hormones, of which cortisol is one. Cortisol is the 'stress hormone'. Its release triggers negative feedback to the hypothalamus and anterior pituitary, thus resulting in a drop of circulating ACTH and cortisol levels. Cortisol also initiates metabolic effects which facilitate a return to homeostatsis.

Introduction to the neural mechanisms of appetite control and the interconnections to the HPA axis

In the paragraph above we were introduced to the HPA axis and what it entails. This section aims to give a general understanding to how the brain is involved in regulating appetite, and how it is connected to the HPA axis to allow for stress to have an impact on appetite, which will be discussed in greater detail further along.

In light of the current obesity epidemic there has been a great deal of research into exactly what causes an obese person to over-eat, or store more energy than a normal weight person. This section aims to highlight the key features so that the connection between stress and appetite can be made.

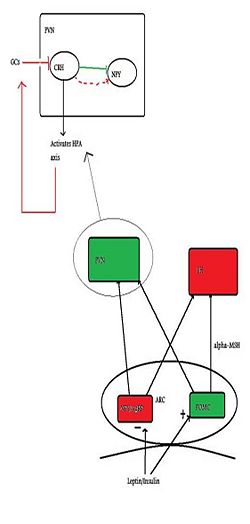

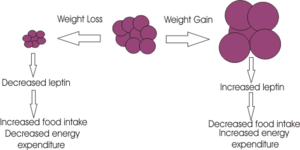

Several peptides circulating in our bodies inform the brain of the body’s nutritional status. Insulin and leptin, (which both acts to suppress appetite) and ghrelin (which induces appetite) are all thought to be able to cross the blood-brain barrier and enter the hypothalamus via thearcuate nucleus (ARC) which is one important site of action. In the arcuate nucleus there are populations of neurons which produce and release substances which have either orexigenic effects (induce feeding) or anorexigeninc effects (suppress feeding). The orexigenic neurons, which signal hunger, or a negative energy state, co-express two orexigenic peptides: neuropeptide Y (NPY), and Agouti-related Peptide (AgRP). These neurones are inhibited by increased levels of insulin and leptin. However, insulin and leptin have excitatory effects on another type of neuron, anorexigenic neurons that express pro-opiomelanocortin (POMC) which releases pro-opiomelanocortin, which is further cleaved into melanocortins. One of the key melanocortins here is alpha-MSH, a potent anorexigenic molecule, which acts on the MC4 receptor to suppress feeding/hunger. An additional feature of the orexigenic pathway is that AgRP is an inverse agonist at the MC4 receptor, thus increasing NPY/AgRP neurons orexigenic power [1]

Appetite-regulating neurons of the arcuate nucleus project to other parts of the hypothalamus, such as to the lateral hypothalamus (LH), and the paraventricular nucleu (PVN) and it is here the second-order signalling is postulated to take place. PVN stimulation causes inhibition of eating, whilst LH stimulation has the opposite effect. (Schwartsz et al, 2000). It is in the PVN we see the interconnection between feeding control and the HPA (stress) axis and it is here where the main activator of the HPA axis, Corticotropin-releasing factor (CRF), is synthesised. It has been demonstrated that NPY neurons have abundant projections here, and that they are in close proximity to CRF cell bodies (Demitrov et al, 2007). (Demitrov et al, (2007), also showed that NPY had a stimulatory effect on CRF release, indicating that hunger can cause stress, but this will not be discussed here).

Studies by Jhanwar-Uniyal et al. (1993) demonstrated two important findings, first that PVN is indeed innervated by NPY neurons projecting from the ARC (shown by correlation of NPY levels in the PVN and ARC, this correlation did not exist for other hypothalamic areas) and secondly, they found that direct injection of NPY into the PVN potently affected eating behaviour, leading to an increase of ingestion of carbohydrate dense food (no increase was seen in ingestion of protein and fat). This preference for carbohydrate dense food when stressed; and the biological relevance, will be discussed further along.

So as stated above, the key area of connection between the HPA axis and regulation of feeding is the PVN. Here there are innervating NPY neurons (Orexigenic) and CRF synthesis (Activator of the HPA axis) which seem to act on each other in a classic feedback loop. CRF inhibits NPY thus initially being anorexigenic, however, once it has activated the HPA axis and glucocorticoids (GCs) are produced which then feed back to the brain and inhibit CRF, this inhibition is blocked, and feeding occurs. The more GCs present in the body (ie sustained activation of the HPA axis) the greater the inhibition of the CRF inhibition on NPY, thus, GCs stimulate NPY resulting in an orexigenic drive. However, as said, GCs inhibit CRF release which downstream will stop the release of GCs, thus completing the feedback loop (Cavagnini et al, 2000).

The control of appetite is immensely complex and this section only offers a brief overview (please see references for more detail). As has been described, there are several mechanisms in which appetite and stress are related to each other, and the significance of this will be discussed further along. The aim behind most research done in this field is to offer a solution to the growing morbidity of our generation as a result of obesity. Stress-induced eating has been shown to play a part in the obesity epidemic and it is the main objective of this paper to discuss the impact of stress on eating.

Acute Stress and Appetite

Why do you reach for that extra double chocolate chip cookie after a stressful day?

Stress is known to affect every body system and contributes to many of the negative health behaviours which impact todays’ society, including cardiovascular disease, diabetes and hypertension. With obesity becoming the world-wide epidemic which underlies many of these life-threatening diseases, many researchers have chosen to study the connection between novel stressors and an individuals eating behaviour, for example amount of food eaten and choice of food. There appear to be two ways in which our bodies’ can respond to stress, either by over or under-eating; both of which are explained in this section.

HPA Axis – ‘Uncontrollable Stress’

Both human and rodent studies into this area have illustrated a greater caloric intake during the recovery period from a novel stressor. Sapolsky’s perceives this response to be due to the appetite stimulating effects of the residual cortisol in the blood-stream following an acute stressor…..

Sympathetic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis – ‘Controllable Stress’

However, several studies have also shown a suppression of eating in response to acute stress. In certain stressful situations, sometimes termed ‘controllable’ stressors, the ‘Fight or Flight’ response is activated rather than the HPA axis. This mechanism, caused by the release of catecholamines from the adrenal glands, namely Adrenaline and Noradrenaline causes a range of physiological and behavioural changes to allow the individual to cope with the situation. One such change is a reduction in food intake in the short term through a slowed gastric emptying and shunting of the blood vessels to the gastrointestinal tract to allow the muscles an increased blood supply. (Do you want me to expand on this, effects on Nor and Adr??)

The psychology behind the link between stress and eating

Stress can have influences on eating behaviours in two ways; it can either cause under or over eating. Most people tend to change their eating patterns when they are experiencing stressful situations, for example an individual who is under extreme pressure at work would be more likely to choose to eat food high in sugar and fat, which in the long term could lead to weight gain and ultimately obesity. Similarly, one study demonstrated that people in a sad state were more inclined to eat high sugar and fat food whereas people who ate during a happy state were more likely to eat healthier food such as dried fruit. It is also thought that people who are already classified as being overweight or obese are expected to put on even more weight when they are under periods of stress.

In recent years there has been much interest and research into the physiology behind eating behaviours but it has become obvious that both internal and external factors can have an effect on an individual’s feelings and any consequences which arise due to this.

Studies have shown that glucocorticoids play a major role in eating behaviours and also in learning, memory and habit formation. It has been shown that stress-induced increases in glucocorticoid secretion have an intensifying effect on emotions and motivation and it also appears to increase calorie intake. As glucocorticoids increase so does insulin secretion which is a key feature of type 2 diabetes which can occur as a result of obesity. Insulin is thought to have a role in the selection of food, whilst glucocorticoids increase the motivation for choosing a particular food.

There is a relationship between individuals who are feeling stressed prior to eating and then feeling better after they have eaten highly palatable foods. Infrequent eating of pleasurable foods when under a period of stress will not lead to obesity but eating pleasurable foods more often will develop habits to try to relieve the stress and in the long term this can lead to weight gain and obesity.

About References

To insert references and/or footnotes in an article, put the material you want in the reference or footnote between <ref> and </ref>, like this:

<ref>Person A ''et al.''(2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 36:36-52</ref> <ref>Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference ''J Neuroendocrinol'' 25:262-9</ref>.

Look at the reference list below to see how this will look.[2] [3]

If there are more than two authors just put the first author followed by et al. (Person A at al. (2010) etc.)

Select your references carefully - make sure they are cited accurately, and pay attention to the precise formatting style of the references. Your references should be available on PubMed and so will have a PubMed number. (for example PMID: 17011504) Writing this without the colon, (i.e. just writing PMID 17011504) will automatically insert a link to the abstract on PubMed (see the reference to Johnsone et al. in the list.)

[4]

Use references sparingly; there's no need to reference every single point, and often a good review will cover several points. However sometimes you will need to use the same reference more than once.

How to write the same reference twice:

Reference: Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591

First time: <ref name=Berridge07>Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. ''Psychopharmacology'' 191:391–431 PMID 17072591 </ref>

Second time:<ref name=Berridge07/>

This will appear like this the first time [5] and like this the second time [5]

Figures and Diagrams

You can also insert diagrams or photographs (to Upload files Cz:Upload)). These must be your own original work - and you will therefore be the copyright holder; of course they may be based on or adapted from diagrams produced by others - in which case this must be declared clearly, and the source of the orinal idea must be cited. When you insert a figure or diagram into your article you will be asked to fill out a form in which you declare that you are the copyright holder and that you are willing to allow your work to be freely used by others - choose the "Release to the Public Domain" option when you come to that page of the form.

When you upload your file, give it a short descriptive name, like "Adipocyte.png". Then, if you type {{Image|Adipocyte.png|right|300px|}} in your article, the image will appear on the right hand side.

References

- ↑ Schwartz M et al. (2000) Central nervous system control of food intake. Nature 404:661-671 PMID 10766253

- ↑ Person A et al. (2010) The perfect reference for subpart 1 J Neuroendocrinol 36:36-52

- ↑ Author A, Author B (2009) Another perfect reference J Neuroendocrinol 25:262-9

- ↑ Johnstone LE et al. (2006)Neuronal activation in the hypothalamus and brainstem during feeding in rats Cell Metab 2006 4:313-21. PMID 17011504

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Berridge KC (2007) The debate over dopamine’s role in reward: the case for incentive salience. Psychopharmacology 191:391–431 PMID 17072591