Gertrude Bell: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

||

| Line 35: | Line 35: | ||

She enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in 1886.<ref>Winstone, p. 13</ref> | She enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in 1886.<ref>Winstone, p. 13</ref> | ||

While women still could not receive degrees at Oxford, she did earn a "First" at [[Oxford]], in Modern History. No woman had previously won first-class honors in any field. | |||

==Educational travel== | ==Educational travel== | ||

Within the culture of the time, however, she was an apparent failure, as no one had asked for her hand in marriage. <ref>Wallach, pp. 24-25</ref> | Within the culture of the time, however, she was an apparent failure, as no one had asked for her hand in marriage. <ref>Wallach, pp. 24-25</ref> | ||

Revision as of 10:14, 4 December 2009

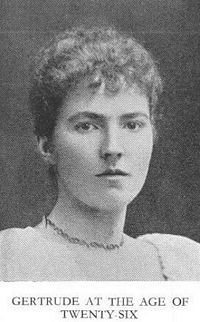

Gertrude Margaret Lothian Bell (1868-1926) was an English author and adventurer who influenced the formation of Iraq, when, in 1932, that state gained independence from the United Kingdom. At a memorial service for her in 1927, at the Royal Geographic Society, she was called the most powerful woman in the British Empire after the First World War, the "uncrowned queen of Iraq", and possibly the brains behind T. E. Lawrence and the definer of Mideast policy for Winston Churchill.[1]

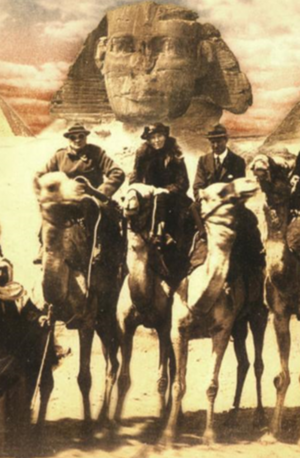

A 1921 photograph is informative in multiple ways. Taken on 22 March, the "last day of the Cairo Conference and the final opportunity for the British to determine the postwar future of the Middle East. Like any tourist, the delegation makes the routine tour of the pyramids and have themselves photographed on camels in front of the Sphinx. Standing beneath its half-effaced head, two of the most famous Englishmen of the twentieth century confront the camel in some disarray: Colonial Secretary Winston Churchill, who has just, to the amusement of all, fallen off his camel, and T. E. Lawrence, tightly constrained in the pin-striped suit and trilby of a senior civil servant. Between then, at her ease, rides Gertrude Bell, the sole delegate possessing knowledge indispensable to the Conference. Her face, in so far as it can be seen beneath the brim of her rose-decorated straw hat, is transfigured with happiness. Her dream of an independent Arab nation is about to come true, he choice of a king endorsed: her Iraq is about to become a country. Just before leaving the hotel that morning, Churchill has cabled to London the vital message "Sharif's son Faisal offers hope of best and cheapest solution."[2]

There are eerie parallels to today's situation in Iraq "...Faisal, the protege of Bell and T. E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia), was imported from Mecca to become the "roof." In early 2004, David Ignatius wrote in the Washington Post about the offer of Prince Hassan of Jordan, the great nephew of Faisal, to mediate among Iraqi religions factions to bring them together and become a "provisional head of state."[3]

Early life

Her mother died when Gertrude was three, after her brother Maurice's birth. This increased her bonds with her father, Hugh. She was a literate child; in the first known letter, written when she was five, she told her grandmother, "My dolls have given me great amusement. You wer very good to get them for me." Her governesses found her a "handful". Her father remarried when she was eight, and she formed an excellent relationship with her stepmother, Florence Oliff.

She led her brother Maurice into endless adventures, with Maurice often falling from walls while Gertrude landed gracefully, a foretaste of her later mountaineering.

Unusually for a girl in the late 19th centure she went to Queen's College in Harley Street, first as a day scholar living with her maternal grandmother, and then as a boarder. She was emphatic about the studies she liked and disliked, and rejected music and Scripture. [4]

University

The Bell family had been growing in status during her girlhood, opening opportunities. [5]

She enrolled at Lady Margaret Hall, Oxford, in 1886.[6]

While women still could not receive degrees at Oxford, she did earn a "First" at Oxford, in Modern History. No woman had previously won first-class honors in any field.

Educational travel

Within the culture of the time, however, she was an apparent failure, as no one had asked for her hand in marriage. [7]

Romania

To correct her perceived failings, family friends, the Lascelles family, invited her to spend the winter season of 1889 in Bucharest, Romania. Whatever this may have done for her social life, it was her introduction to the diplomatic world, and to Turkey and the Ottoman Empire.

Persia

Travel was an acceptable second chance, in the times, to find a husband. Before traveling to Persia, however, she studied Farsi and gained conversational and reading knowledge. [8] In 1892, she journeyed to visit an uncle, who was then the British Ambassador to Persia, stationed in Tehran. She was impressed with a young diplomat, Henry Cadogan, with whom she had both an emotional and intellectual connection, with whom she could "talk vigorous politics." His income, however, was small.[9] When he asked her father for her hand in marriage, but was refused. Cadogan died of cholera in 1893. [10]

She continued her Farsi studies, using French with a native tutor. Upon her return in 1894, she published a small book, calledd "safar Nameh " i.e., "Persian Pictures." This was followed by a translation of the Divan of Hafiz in 1897. Lady Bell observes the breadth of her standards of comparison: "She draws a parallel between Hafiz and his contemporary Dante: she notes the similarity of a passage with Goethe: she compares Hafiz with Villon, on every side gathering fructifying examples which link together the inspiration of the West and of the East."

Europe

In April 1893, she spent time in Weimar, studying German, and then returned to Britain until 1896. Lady Bell reports no surviving letters until 1896, when she spent some time in Italy, again studying the language.

Jerusalem and environs

After an around-the-world trip, in November 1899 she journeyed to Jerusalem. Lady Bell said she intended to learn more Arabic, arranging studies "Dr. Fritz Rosen was then German Consul at Jerusalem. He had married Nina Roche, whom we had known since she was a child, the daughter of Mr. Roche of the Garden House, Cadogan Place. Charlotte Roche was Nina's sister. " She found Arabic difficult, but continued to study 4-6 hours per day. With the Rosens, she had her first contact with the Druze. [11]

Search for new governance

She recognized that the dominant dynasties were to be the House of Saud (i.e., Wahabbis) of Ibn Saud and the Hashemites of Faisal.[12]

By 1918, Britain was searching for a king or other acceptable ruler of the area that was to become Iraq. Russian revolutionaries had stirred the situation by releasing the Sykes-Picot Agreeement. [12]

Iraq

References

- ↑ Janet Wallach (1999), Desert Queen, Anchor Books, Random House, ISBN 1400096197, p. xxi

- ↑ Georgina Howell (2006), Gertrude Bell: Queen of the Desert, Shaper of Nations, Farrar, Straus and Giroux, ISBN 978037416120, p. 3

- ↑ Barbara Furst (2005), "Deja vu all over again, Gertrude Bell and modern Iraq, the extraordinary Englishwoman who played a key role in the formation of modern Iraq confronted many of the same problems the U.S. and Iraq face today", AmericanDiplomacy.org

- ↑ Elizabeth Burgoyne (1958), Gertrude Bell: From her personal papers, 1889-1914, Ernest Benn, pp. 15-16

- ↑ H.V.F. Winstone (1978), Gertrude Bell, Quartet Books, ISBN 070422203x, pp. 10-12}}

- ↑ Winstone, p. 13

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 24-25

- ↑ Lady Bell, D.B.E., ed. (1927), The Letters of Gertrude Bell, vol. 1, Boni and LiverightLetter to Horace Marshall, Gulahek, June 18, 1892

- ↑ Burgoyne, pp. 28-29

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 33-37

- ↑ Wallach, pp. 51-54

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Christopher Hitchens (June 2007), "The Woman Who Made Iraq", The Atlantic

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Archaeology Workgroup

- Politics Workgroup

- International relations Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Archaeology Content

- Politics Content

- History tag

- Archaeology tag

- International relations tag