Amy Lowell (poet): Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) (adding how she is related to the other two Lowells) |

||

| (16 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

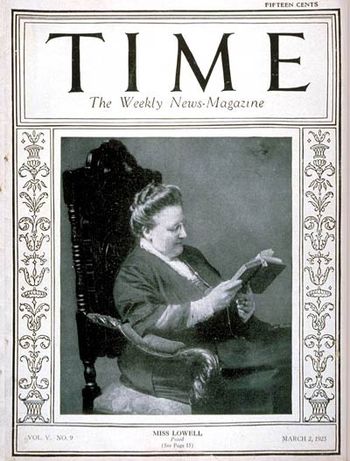

{{Image|Amy Lowell Time magazine cover 1925.jpg|right|350px|Amy Lowell on the cover of Time magazine, March 2, 1925. This issue included a favorable review of Amy Lowell's biography of [[John Keats]].}} | {{Image|Amy Lowell Time magazine cover 1925.jpg|right|350px|Amy Lowell on the cover of Time magazine, March 2, 1925. This issue included a favorable review of Amy Lowell's biography of [[John Keats]].}} | ||

'''Amy Lowell''' (1874-1925) was a modern American poet, literary critic and biographer. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry posthumously in 1926. Educated privately, she was born and died in Brookline, Massachussetts. During her lifetime, her work was largely overshadowed and overlooked by her more famous relatives, [[James Russell Lowell]] and [[Robert Lowell]]. Although she authored hundreds of poems, only a few have | '''Amy Lowell''' (1874-1925) was a modern American poet, literary critic and biographer. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry posthumously in 1926. Educated privately, she was born and died in Brookline, Massachussetts. During her lifetime, her work was largely overshadowed and overlooked by her more famous relatives, her grand-uncle [[James Russell Lowell]] and her nephew [[Robert Lowell]]. Although she authored hundreds of poems, only a few have appeared in contemporary poetry compendiums. | ||

In England in 1913, she associated with Ezra Pound and others of the English [[Imagist poets|imagist poets]], who objected to the over-flowerly language of the ''romantic'' poets. Amy Lowell's three-volume anthology, ''Some Imagist Poets'' (1915-17), made the imagist movement famous and annoyed Pound, who considered her to have hi-jacked a movement which was rightly his to claim. Lowell's poetry is considered to be an example of the imagist movement because it favors precision of imagery, clear language, directness of presentation and free verse. A characteristic feature of the form is its attempt to isolate a single image to reveal its essence. | |||

{{TOC}} | {{TOC}} | ||

== Amy Lowell books == | == Amy Lowell books == | ||

Most of Amy Lowell's original books are available today at Project Gutenberg<ref>[https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/ | Most of Amy Lowell's original books are available today at Project Gutenberg<ref>[https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/147 Amy Lowell works] on [[Project Gutenberg]], last access 8/6/2022</ref>. Listed below are the books she published during her lifetime. | ||

Stories: | Stories: | ||

| Line 15: | Line 16: | ||

Poetry: | Poetry: | ||

* 1912: Her first volume of poetry, ''A | * 1912: Her first volume of poetry, ''A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass'' | ||

* 1914: Poetry in ''Sword Blades and Poppy Seed'' began to include experiments with "unrhymed cadence" and "polyphonic prose" | * 1914: Poetry in ''Sword Blades and Poppy Seed'' began to include experiments with "unrhymed cadence" and "polyphonic prose" | ||

* 1916: ''Men, Women and Ghosts'' | * 1916: ''Men, Women and Ghosts'' | ||

| Line 31: | Line 32: | ||

== Patterns: A poem == | == Patterns: A poem == | ||

''Patterns'', by Amy Lowell was | ''Patterns'', by Amy Lowell was originally published in her 1916 book ''Men, Women and Ghosts''. It is valued for its anti-war sentiment and is one of her works that has been frequently reprinted in anthologies: | ||

<poem style="border: 2px solid #d6d2c5; background-color: #f9f4e6; padding: 1em;"> | <poem style="border: 2px solid #d6d2c5; background-color: #f9f4e6; padding: 1em; width: 40%;"> | ||

I walk down the garden paths, | I walk down the garden paths, | ||

And all the daffodils | And all the daffodils | ||

| Line 148: | Line 149: | ||

In a pattern called a war. | In a pattern called a war. | ||

Christ! What are patterns for? | Christ! What are patterns for? | ||

</poem> | </poem> | ||

== Footnotes == | == Footnotes == | ||

Latest revision as of 20:45, 25 September 2022

Amy Lowell (1874-1925) was a modern American poet, literary critic and biographer. She won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry posthumously in 1926. Educated privately, she was born and died in Brookline, Massachussetts. During her lifetime, her work was largely overshadowed and overlooked by her more famous relatives, her grand-uncle James Russell Lowell and her nephew Robert Lowell. Although she authored hundreds of poems, only a few have appeared in contemporary poetry compendiums.

In England in 1913, she associated with Ezra Pound and others of the English imagist poets, who objected to the over-flowerly language of the romantic poets. Amy Lowell's three-volume anthology, Some Imagist Poets (1915-17), made the imagist movement famous and annoyed Pound, who considered her to have hi-jacked a movement which was rightly his to claim. Lowell's poetry is considered to be an example of the imagist movement because it favors precision of imagery, clear language, directness of presentation and free verse. A characteristic feature of the form is its attempt to isolate a single image to reveal its essence.

Amy Lowell books

Most of Amy Lowell's original books are available today at Project Gutenberg[1]. Listed below are the books she published during her lifetime.

Stories:

- 1887: Her first book, Dream Drops, contained fairy tales. It was published privately.

Poetry:

- 1912: Her first volume of poetry, A Dome of Many-Coloured Glass

- 1914: Poetry in Sword Blades and Poppy Seed began to include experiments with "unrhymed cadence" and "polyphonic prose"

- 1916: Men, Women and Ghosts

- 1918: Can Grande's Castle

- 1919: Pictures of the Floating World shows Chinese and Japanese influence

- 1921: Legends

- 1921: Fir-Flower Tablets

Literary criticism, biography and other poets:

- 1915/1916/1917: Some Imagist Poets, a three-volume anthology which made the imagist movement famous

- 1915: Six French Poets: Studies in Contemporary Literature

- 1917: Tendencies in Modern American Poetry

- 1925: John Keats (acclaimed biography)

Patterns: A poem

Patterns, by Amy Lowell was originally published in her 1916 book Men, Women and Ghosts. It is valued for its anti-war sentiment and is one of her works that has been frequently reprinted in anthologies:

I walk down the garden paths,

And all the daffodils

Are blowing, and the bright blue squills.

I walk down the patterned garden paths

In my stiff, brocaded gown.

With my powdered hair and jewelled fan,

I too am a rare

Pattern. As I wander down

The garden paths.

My dress is richly figured,

And the train

Makes a pink and silver stain

On the gravel, and the thrift

Of the borders.

Just a plate of current fashion,

Tripping by in high-heeled, ribboned shoes.

Not a softness anywhere about me,

Only whale-bone and brocade.

And I sink on a seat in the shade

Of a lime tree. For my passion

Wars against the stiff brocade.

The daffodils and squills

Flutter in the breeze

As they please.

And I weep;

For the lime tree is in blossom

And one small flower has dropped upon my bosom.

And the plashing of waterdrops

In the marble fountain

Comes down the garden paths.

The dripping never stops.

Underneath my stiffened gown

Is the softness of a woman bathing in a marble basin,

A basin in the midst of hedges grown

So thick, she cannot see her lover hiding,

But she guesses he is near,

And the sliding of the water

Seems the stroking of a dear

Hand upon her.

What is Summer in a fine brocaded gown!

I should like to see it lying in a heap upon the ground.

All the pink and silver crumpled up on the ground.

I would be the pink and silver as I ran along the paths,

And he would stumble after

Bewildered by my laughter.

I should see the sun flashing from his sword hilt and the buckles

on his shoes.

I would choose

To lead him in a maze along the patterned paths,

A bright and laughing maze for my heavy-booted lover,

Till he caught me in the shade,

And the buttons of his waistcoat bruised my body as he clasped me,

Aching, melting, unafraid.

With the shadows of the leaves and the sundrops,

And the plopping of the waterdrops,

All about us in the open afternoon--

I am very like to swoon

With the weight of this brocade,

For the sun sifts through the shade.

Underneath the fallen blossom

In my bosom,

Is a letter I have hid.

It was brought to me this morning by a rider from the Duke.

“Madam, we regret to inform you that Lord Hartwell

Died in action Thursday sen'night.”

As I read it in the white, morning sunlight,

The letters squirmed like snakes.

“Any answer, Madam,” said my footman.

“No,” I told him.

“See that the messenger takes some refreshment.

No, no answer.”

And I walked into the garden,

Up and down the patterned paths,

In my stiff, correct brocade.

The blue and yellow flowers stood up proudly in the sun,

Each one.

I stood upright too,

Held rigid to the pattern

By the stiffness of my gown.

Up and down I walked,

Up and down.

In a month he would have been my husband.

In a month, here, underneath this lime,

We would have broke the pattern.

He for me, and I for him,

He as Colonel, I as Lady,

On this shady seat.

He had a whim

That sunlight carried blessing.

And I answered, “It shall be as you have said.”

Now he is dead.

In Summer and in Winter I shall walk

Up and down

The patterned garden paths

In my stiff, brocaded gown.

The squills and daffodils

Will give place to pillared roses, and to asters, and to snow.

I shall go

Up and down,

In my gown.

Gorgeously arrayed,

Boned and stayed.

And the softness of my body will be guarded from embrace

By each button, hook, and lace.

For the man who should loose me is dead,

Fighting with the Duke in Flanders,

In a pattern called a war.

Christ! What are patterns for?

Footnotes

- ↑ Amy Lowell works on Project Gutenberg, last access 8/6/2022