Marshall Plan

The Marshall Plan (officially the European Recovery Program or ERP) was a system of American economic aid to Western Europe after World War II that played a major role in the economic recovery, modernization, and unification of Europe. In three years 1948-51 the ERP gave away $12.4 billion (about 5% of the 1948 GDP of $270 billion) for modernizing the economic and financial systems and rebuilding the industrial and human capital of war-torn Europe, including Britain, Germany, France, Italy and smaller nations. It required each government to set up a national economic plan, and for the countries to cooperate in terms of financial and trade flows. The money was not a loan and there was no repayment. Washington spent such vast sums because it was believed to be cheaper than the rearmament that isolationism or rollback would entail. In the long run, the logic went, a prosperous Europe would be more peaceful, and would make its main trading partner, the US, more prosperous.

When Joseph Stalin, the Communist dictator of the Soviet Union, refused to participate or allow any of his satellites in eastern Europe to participate, the plan became exclusive to western Europe. Europe split along East-West lines that defined the Cold War. Named after U.S. Secretary of State George C. Marshall, the plan was designed and operated by State Department officials, especially Dean Acheson in 1947 and began in 1948 when the Republican-controlled Congress authorized the program and the money. The Marshall Plan ended in late 1951, when it gave way to the Mutual Security Program, which combined economic and military aid.

Historians no longer argue that the Marshall Plan was essential for Europe's recovery, but rather that its political and psychological impact was decisive in shaping Western Europe. The powerful combination of ERP and NATO gave Europe the assurance of America's commitment to the security and prosperity of Western Europe, and helped the recipients avoid the pessimism and despair that characterized the aftermath of World War I. The Marshall Plan thus created in Europe an unstoppable "revolution of rising expectations," the striking phrase coined in 1950 by Harlan Cleveland, an economist and senior ERP official.

Origins

Six years of total war in Europe, 1939-1945, brought destruction and economic ruin to both victors and vanquished. Only the USA emerged from World War II without domestic damage and stronger economically than before the war. The armadas of heavy bombers that night and day had blasted every industrial area and transportation center in Europe had done a thorough job; recovery was painfully slow. Economic output in 1948 was 13% below 1938 levels; in Germany it was 55% lower. America, in startling contrast, was 65% higher.

Signs of permanent stagnation were pervasive, coupled with growing frustration and pessimism about the future. Millions of refugees lived in squalid camps. Britain had won the war, and it had received billions of dollars in postwar loans, but its economy was shattered; bread had to be rationed. Winston Churchill said Europe was "a rubble-heap, a charnel house, a breeding ground of pestilence and hate." Conditions were even worse in the Soviet Union, but Stalin’s army and secret police were everywhere, and he used the vacuum in eastern Europe to expand Soviet influence and control.

By 1946 Winston Churchill warned that the Soviet Union had drawn an “iron curtain” which divided Europe between rival alliances and ideologies. Sensing that his dreaded enemy capitalism was collapsing, Stalin ordered the Communist parties in every country to shift to the left and fight the class enemy. The danger he saw was that the American juggernaut would impose its hated values, promoting liberalism, free speech, free elections, and capitalism.

In 1947 the Truman Doctrine of military support saved Greece from a Communist takeover (and aided Turkey too), but Americans feared that the Communists had a good chance to seize political power in Italy and France, shutting out American trade, cultural exchanges and political values in a victory for totalitarianism over democracy.

Postwar ad-hoc grants and loans

In addition to the $12.4 billion Marshall plan money, the U.S. gave an additional $20 billion in grants and net credits from 1945 through 1951. They were aimed at short-term needs and did not carry the long-terms modernization goals of the Marshall Plan, but they did pump very large sums into war-torn economies.[1] In 1945-47, before the Marshall Plan started, aid amounted to $13.1 billion. Postwar relief through the UN (UNNRA) came to $3.5 billion. Britain received a long-term loan of $3.75 billion in 1946. West Germany (that is the Allied-occupied part of the country) received U.S. goods through the GARIOA program (Government and Relief in Occupied Areas) valued at $1.7 billion. Aid to Greece and Turkey began in 1947 with the Truman Doctrine's allocation of $650 million.[2]

Long-term solution

In 1948 State department official Will Clayton found a long-term umbrella solution, named the “European Recovery Program” or ERP. He envisioned gigantic American gifts of billions of dollars that would never have to be repaid, combined with specific European initiatives that would put the continent’s industry, transportation, finance and farming on a sound basis. That would promote free trade and a healthy environment for economic and political freedoms, and in the long run, lead to the sort of unity that was eventually reached by the European Union.

The Administration requested $14.2 billion; Congress authorized $13.4 billion, and $12.5 billion was spent by the time the plan officially ended (and was replaced by another aid program that stressed military support.) The sum of $14 billion is sometimes cited, which included aid to Japan and other Asian countries given on similar terms (but with a different administrative structure). In Europe, the largest grants went to Britain ($3.4 billion), France ($2.7 billion), Italy ($1.5 billion), West Germany ($1.4 billion), Netherlands ($1.1 billion), Greece ($796 million), Austria ($678 million), and Belgium ($559 million). Spain was excluded because of lingering resentment regarding the Spanish Civil War.

Building support

Success required the use of Secretary of State George Marshall’s enormous prestige, evident in his speech[3] at Harvard University in June 1947 and of course in the informal name of the whole program. Even more essential was close collaboration with the Republicans who controlled Congress, especially their foreign policy leader, Senator Arthur Vandenberg. Vandenberg, who had shepherded the Truman Plan through Congress in 1947, was a critical supporter and won Congressional approval for the much more expensive Marshall Plan. All of Europe was invited to join, along with much of Latin America.[4]

American and European newspapers, political parties, businesses, labor unions, and intellectuals supported a massive promotional campaign that warned that the isolationist mistakes following World War I must not be repeated. In the United States some critics complained about a "global WPA" (wee WPA) but little organized opposition emerged, apart from far-left elements in some labor unions. Most Americans were exhausted from war and wanted to return to domestic concerns, and reduce heavy wartime taxes; vast new spending programs threatened these goals. ERP supporters answered that America’s national security was at stake, and rebuilding Europe now would be far cheaper than fighting a third world war. The isolationism among conservative Republicans crumbled when the Stalinist seizure of Czechoslovakia in February 1948 showed time was running out.

Building support in Europe

At first most European leaders embraced the plan, but the Communists swung into opposition once Stalin signaled his opposition. However the socialist movements endorsed and supported the ERP as did business and liberal elements. A European organization was formed, the Organization for European Economic Cooperation (OEEC) to coordinate policies, and at all times the details and operations of the program was negotiated between the U.S. and European nations.

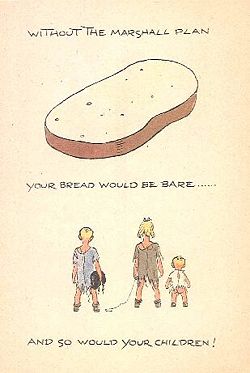

Promotions continued after the plan began, and emphasized its success in contrast to the economic failures under Communism. As the aim of the Marshall Plan was to restore the confidence of the Europeans after the devastation of the war , the ideological and psychological aspects of the plan were as important as the economic ones. Propaganda and publicity campaigns were therefore crucial to the success of the plan and varied little from country to country, as the purpose was to spread the American way of life throughout Europe. For example, American and Danish authorities cooperated with considerable success in 1948-50 to present the Marshall Plan as a program of reciprocal benefit to both nations. Press releases, journalists' tours, and three large exhibitions presented Denmark and the United States as closely related lands with shared values of democracy and freedom. America was depicted as rich and highly developed economically and technologically, while Denmark had superior systems of agriculture and social welfare. Politics was kept in the background in building this image of shared values and interests.[5]

The US State Department used household exhibitions in West Berlin as a propaganda tool to promote the benefits of the ERP, democratic freedom, and individual consumption. Prominent designers and architects designed the exhibitions, which often opened on socialist holidays, thereby ensuring that large numbers of visitors would come from East Berlin. The exhibitions presented a stark contrast between the broad-based consumerism of the West and the tight restrictions and scarcity of Communist Eastern Europe. In addition, the products on display served to undermine the widespread European belief that there was an inherent contradiction between high culture and American mass consumption. The effectiveness of this campaign led the Soviet Union to launch its own program of "consumer socialism," or citizen enfranchisement through consumer rewards, which was modeled on the West.[6]

An opinion poll sponsored by ECA in mid-1950 interviewed 2,000 people in France, Norway, Denmark, Holland, Austria and Italy. In all, 80% knew of the ERP and 75% Between 25% and 40% had an understanding of how it worked. The hardest audience to reach were the workers and the peasants. It was they who doubted most profoundly the motives behind American action, just as Communist propaganda prompted them to do.[7]

Soviet opposition

Although the ERP invited the Soviet Union, Stalin refused to participate. Communist parties mobilized anti-American sentiments across western Europe in a futile effort to stop the ERP. Stalin also forbade his satellites in eastern Europe to accept the American invitation to join the ERP.[8] (Finland also took his advice not to join.) Instead he imposed the “Molotov Plan” that integrated eastern Europe into the poverty-stricken Soviet economy. The inevitable result was that year by year the eastern bloc fell further behind economically, a trend especially visible when comparing West Germany and Communist East Germany.

Operation of ERP

The ERP was run by the Economic Cooperation Administration (ECA), an American State Department division headed 1948-50 by Paul Hoffman (1891-1974), an automobile executive with the skills of a master salesman. The ECA demanded that recipients devise plans to put their financial houses in order with taxes, monetary policies and spending policies geared primarily to recovery, rather than partisan politics. The plans had to be integrated with one another and be so specific that Americans experts could examine and approve the details. Europe did so, asking $29 billion over four years. The United States finally gave $13.4 billion over four years; each year it was about 1 percent of the American Gross Domestic Product. It was the equivalent of $600 billion in 2005 dollars, but the money went much farther because Europe did not start from scratch—it had enormous reservoirs of human talent and organizational skills, and a large but broken infrastructure that could be fixed.

The American grants included currency for loans, but went primarily (70%) towards the purchase of commodities from U.S. and Canadian suppliers: $3.5 billion was spent on raw materials; $3.2 billion on food, feed and fertilizer; $1.9 billion on machinery and vehicles; $1.6 billion on fuel.

The OEEC decided which country should get what and the ECA arranged for the transfer of the goods. The American (and Canadian) suppliers were paid in dollars, which were credited against the appropriated ERP funds. The European recipient, however, was not given the goods as a gift, but had to pay for them in local currency, which was then held by the government in a counterpart fund. That is, all the counterpart money was kept by the European governments (the U.S. was not repaid), with the counterpart funds earmarked for further investment projects.

ERP projects increased agricultural and mining output, repaired the shattered railroad network, and modernized factories (usually with new machines purchased from American companies). Each country increased its exports so its prosperity would be self-sustaining, and they all joined together to reduce tariffs and trade barriers. Europeans came to admire and eventually copy American managerial techniques, oriented toward efficiency rather than traditionalism. Traditionalists grumbled that their old culture would be steamrollered by the Yankees. The results were quickly apparent as each economy began to soar. Germans, the most grateful recipients, still speak of their “economic miracle.” Most important, Europeans recovered the self-confidence that they could create peaceful and prosperous economies, closely aligned with the United States. The Marshall Plan marked a fundamental shift in American culture, from isolationism to internationalism, and from a minor role in world affairs to world leadership. The Marshall Plan made a significant contribution to victory of democracy over totalitarianism in the Cold War (1947-1991). The European Union (EU) can trace its origins to the policy and philosophy of the Marshall Plan.

Labor issues

The "politics of productivity," an attempt to raise levels of industrial productivity in Europe by transcending class conflict and creating a consensus in society for economic growth, was a prominent element in Marshall Plan thinking. It constituted a central focus of the ERP's labor program administered by American trade union officials who staffed the ERP's labor division. This program was supported by the American Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) until hostility to collective bargaining at the local level, combined with the unwillingness of senior Marshall Plan administrators to insist on collective bargaining as the price of receiving American assistance, blighted the project. By contrast to the CIO the rival American Federation of Labor's (AFL) used a more direct strategy of combating communism at the level of organization and propaganda. The competing claims of these two American labor organizations for US government funding became a significant factor in American labor's conduct of Cold War politics.[9]

National studies

Britain

The United Kingdom received $3.2 billion dollars in ERP aid between 1948 and 1951 (in addition to several billions before the ERP began) As with other recipients, the aid was given on the condition that Britain balance its budget, control tariffs, and maintain adequate currency reserves. Marshall Plan aid involved new efforts to increase British industrial productivity. The agency that analyzed the situation, the Anglo-American Council on Productivity (1948-52), tended to compare successful American and British industrial features. American planning and production control, plant layout, management, and psychology of work were admired. Despite participation by trade unions on both sides, the analysis was variously called lop-sided in favor of employers, a misunderstanding of the American system, or a helpful industrial study leading in 1953 to the creation of a long-term program by the British Productivity Council.[10]

During this period, the British Labour government decided to introduce the National Health Service, offering universal health coverage for all citizens, funded out of tax revenues. At first, senior administrators and US leaders supported the Labour Party and its policies, believing that a popular socialist government in Britain was better able to resist Communist influence. However, by 1950, concern was expressed in America that ERP funds were being used to help finance socialist experiments in Britain at the expense of defense spending needed to counter the Soviet threat. British leaders resented what they saw as US interference in domestic politics and in 1951 declared that Britain no longer required Marshall Aid funds.[11]

Belgium

A central goal of the ERP was to promote the growth of productivity along the lines of American management and labor practices. Obstacles arose in Belgium, which clearly limited its impact. The interest among some Belgian employers in increasing rates of productivity per worker was motivated by the evolution of wage levels. But the Americans also intended to inject a new "spirit of productivity" in Belgian industries, which implied, among other measures, a reinforcement of structures of corporatist negotiation between the social partners at a local level. The ambitions of the American strategy therefore extended beyond the defined goal of introducing a Fordist type of economic system with high wages, high productivity, and low prices to consumers. After the belated establishment of the Belgian Office for the Increase of Productivity in 1952, the political character of the program became apparent. By incorporating American management principles, while at the same time decoding them and adapting them to the national situation, Belgian employers' organizations and trade unions skillfully exploited their position as intermediaries in order to appropriate the "modernist" label that they advocated. The "policy of productivity" was successful for a certain time because it matched the contours of the evolution of social reforms in Belgium. This policy success, however, was rendered impotent by the failure of the economic dimension of the productivity campaigns. The Americans had in effect failed to recognize the structural importance of the major financial groups which dominated heavy industry in Belgium. By not adopting the American notions of productivity, and more generally by not carrying out any large-scale programs of innovation and investment in the key sectors that they controlled in the aftermath of the war, these holding companies greatly restricted the scope for American influence. Consequently, it was by other means, such as the training of managers, that the American paradigms entered into Belgian economic culture.[12]

France

Although the economic situation in France was grim in 1945, resources did exist. The US government had planned a major aid program, but President Harry S. Truman unexpectedly ended Lend Lease in late summer 1945, and additional aid was stymied by Congress in 1945-46. France managed to regain its international status thanks to a successful production strategy, a demographic spurt, and technical and political innovations. Conditions varied from firm to firm. Some had been destroyed or damaged, nationalized or requisitioned, but the majority carried on, sometimes working harder and more efficiently than before the war. Industries were reorganized on a basis that ranged from consensual (electricity) to conflictual (machine tools), therefore producing uneven results. Despite strong American pressure through the ERP, there was little change in the organization and content of the training for French industrial managers until the late 1950s. This was mainly due to the reticence of the existing institutions and the struggle among different economic and political interest groups for control over efforts to improve the further training of practitioners.[13]

The Monnet Plan provided a coherent framework for economic policy, and it was strongly supported by the Marshall Plan. It was inspired by moderate, Keynesian free-trade ideas rather than state control. Although relaunched in an original way, the French economy was about as productive as comparable West European countries. [14]

Ireland

Not all of the assistance delivered was in the form of food, finance, and technical advice. Ideological and psychological weapons were also used. Whelan (2006) examines the ERP in Ireland, which had been neutral during the war and wanted to remain neutral afterward. Irish leaders worried that participating in an American program that did not include the Communist nations raised sensitive questions within Ireland about the desirability of being so conspicuously aligned with a Western bloc, and indirectly with Britain. In the end the Irish refused to restructure or modernize their economy and therefore did not realize the gains which had been anticipated with the Marshall Plan.[15]

Italy

In Italy the Marshall Plan's long-term legacy is nuanced and hard to calculate. After Fascism's failure, the United States offered a vision of modernization that was unprecedented in its power, internationalism, and invitation to emulation. However Stalinism was a powerful political force. The ERP was one of the main ways that this modernization was expressed. The old prevailing vision of the country's industrial prospects had been rooted in traditional ideas of craftsmanship, frugality and thrift, which stood in contrast to the dynamism seen in automobiles and fashion, anxious to leave behind the protectionism of the Fascist era and take advantage of the opportunities offered by rapidly expanding world trade. By 1953 industrial production had doubled compared with 1938 and the annual rate of productivity increase was 6.4%, twice the British rate.

At Fiat, automobile production per employee quadrupled between 1948 and 1955, the fruit of an intense, Marshall Plan-aided application of American technology (as well as much more intense discipline on the factory-floor). Vittorio Valletta, Fiat's general manager, helped by trade barriers that blocked French and German cars, focused on technological innovations as well as an aggressive export strategy. He successfully bet on serving the more dynamic foreign markets from modern plants built with the help of Marshall Plan funds. From this export base he later sold into a growing domestic market, where Fiat was without serious competition. Fiat managed to remain at the cutting edge of car manufacturing technology, enabling it to expand production, foreign sales, and profits. [16]

How Italian society built mechanisms to adapt, translate, resist, and domesticate this challenge had a lasting effect on the nation's development over the subsequent decades. [17]

Norway

Given the business background of ECA leaders such as Paul Hoffman, the Americans' readiness to work with the Norwegian Labor government's ERP Council disappointed the conservative Norwegian business community, represented by the major business organizations, the Norges Industriforbund and the Norsk Arbeidsgiverforening. While reluctant to work with the government, Norwegian business leaders also recognized the dangers of appearing to obstruct the implementation of the Marshall Plan. The Americans' acceptance of a role for government in economic planning reflected their New Deal orientation. The opportunities for mediation between conservative Norwegian business interests and the government that arose in the course of administering the Marshall Plan helped establish a base for the emergence of Norwegian corporatism in the 1950s.[18]

Germany

The West German "Wirtschaftswunder," the miraculous economic recovery after 1945, was due to the explosive growth of intra-European trade. After an interlude of Allied administration, the Marshall Plan heralded the reintegration of West Germany into the Western European economy. The emerging postwar settlement facilitated the continuation of the boom in the 1950's. Economic development created additional impetus for further European integration by the end of the decade. France, once fearful of German industrial domination, combined with West Germany to form the European Coal and Steel Community in which they supplied steel for German automobiles. Competition played a role in modernizing the steel industry in both countries.[19]

Comparisons

Western Europe recovered much faster after World War II than after World War I, despite far greater physical and economic damage in 1945 than in 1918. Output grew at 7.5% annually from 1945 to 1950, more than double the 3.5% of 1919-24. Indeed, the rapid recovery in the late 1940s took economists by surprise. One explanation was the large output gap (that is, economic output in 1945 was further below the level of 1938 than that of 1919 to 1914) and a greater capacity to fill that gap (increased industrial capacity as a result of expanded wartime production). Another reason for the improved economic performance in the late 1940's was a general change in domestic political attitudes. After 1918 there were conscious hopes and efforts to revive prewar economic and political structures; no such reactionary calls for a return to the prewar Great Depression existed after 1945. Instead there was a clear desire for change. One measure of a commitment to change was the far slower decontrol of wages, prices, and rents after 1945 to ensure economic stability. Another difference between 1919 and 1946, from a macroeconomic standpoint, was that post-1918 politicians committed themselves to an immediate return to the gold standard with little clear understanding of how national economies worked or were interconnected. In contrast, after 1945 most countries pursued expansionary economic policies with little regard for hard currency stability. A final reason for the difference in the success of postwar reconstruction was a marked change in the nature of international politics, with far more effort being made toward international cooperation after World War II, especially by the 1950's, compared to what happened in the 1920's. This sense of cooperation was complemented by a radically new attitude of the United States toward world affairs: a willingness to participate in the UN; modest reparations demands on Germany; no demand for repayment of war debts; and an active American aid program abroad, in particular the Marshall Plan.[20]

Memory

In America the term “Marshall Plan” became a metaphor used to describe a proposed very expensive government program to solve a major problem.

In 1972 the West German Chancellor Willie Brandt gave a thank-you speech at Harvard and announced the "German Marshall Fund of the United States," an independent American foundation funded by West Germany at 10 million marks a year for 25 years. Its mission is to "increase understanding, promote collaboration, and stimulate exchanges of practical information between the United States and Europe."

Historiography

The first accounts emphasized the economic impact in taking Europe from devastation to prosperity. They were challenged by the revisionist counterfactual analysis of Alan Milward (1984), who said that Europe in 1947 was might have been on the way to prewar levels. Milward does not say the ERP was of no use, he says it is possible it was not essential for European economic indicators to recover to prewar levels.[21]

In turn Milward's conclusions have been challenged by Eichengreen et al. (1992) econometric analysis reasserting the positive impact of the plan through its critical and timely support of basic market systems in fragile European national economies.[22]

De Long and B. Eichengreen (1993) agree with Milward that the $12 billion was too small to significantly impact growth, and that the infrastructure had largely been repaired by the time the ERP began. However it was decisive, they argue, in creating a market that could unleash the European potential. The alternative was a system of government controls that looked backward to the Great Depression, instead of forward to what became an economic miracle. Argentina, for example, did that and never recovered. Specifically the ERP succeeded in dismantling restrictions and controls that impeded progress and restored price stability. They conclude the Marshall Plan should be thought of as "a large and highly successful structural adjustment program."[23]

On the political front the important of the Marshall Plan in halting Soviet expansion has been a major theme. Some leftist historians complain that the goal was to rescue the American capitalist economy--more so than Europe--and to make the world capitalist. Other have argued for a benign Soviet Union that turned hostile only after the Marshall Plan threatened to lure eastern Europe into the western orbit.[24] The Marshall Plan opened up national boundaries to trade and investment and the joining of private and public initiatives within the plan helped lay the groundwork for later European unification, as well as the decisive choice of the American side by western Europe in the emerging Cold War. For the most part the debate depends on whether the historian favored a capitalist or Communist solution to Europe's future (the Socialists in Europe supported the Marshall Plan vigorously, especially in Britain.)

notes

- ↑ Historians who downplay the amount of the Marshall plan money usually ignore the other $20 billion, a sum that had to have some impact.

- ↑ See U.S. Statistical Abstract: 1952 (1953) table 1000 p. 830 online

- ↑ For text see "Marshall Announces His Plan"

- ↑ Switzerland did not officially join, in order to preserve its neutrality. However it was at least partly incorporated into the ERP economic system through the 1949 off-shore trade agreement.

- ↑ Marianne Rostgaard, "Kampen Om Sjaelene: Dansk Marshallplan Publicity 1948-50" [The Battle for Souls: Publicity for the Marshall Plan in Denmark, 1948-50]. Historie 2002 (2): 257-291. Issn: 0107-4725

- ↑ Greg Castillo, "Domesticating the Cold War: Household Consumption as Propaganda in Marshall Plan Germany." Journal of Contemporary History 2005 40(2): 261-288. Issn: 0022-0094 in Ebsco

- ↑ David Ellwood, "'You Too Can Be like Us': Selling the Marshall Plan. History Today 1998 48(10): 33-39. Issn: 0018-2753 in Ebsco

- ↑ In 1948-49, however, the ERP quietly spent $11.2 million to buy Polish coal, thus providing Poland with desperately needed hard currency and creating an informal relationship with Poland.

- ↑ Anthony Carew, "The Politics of Productivity and the Politics of Anti-communism: American and European Labour in the Cold War," Intelligence and National Security 18, no. 2 (2003): 73-91.

- ↑ Anthony Carew, "The Anglo-American Council on Productivity (1948-52): the Ideological Roots of the Post-war Debate on Productivity in Britain." Journal of Contemporary History 1991 26(1): 49-69. Issn: 0022-0094 in Jstor

- ↑ Daniel M. Fox, "The Administration of the Marshall Plan and British Health Policy." Journal of Policy History 2004 16(3): 191-211. Issn: 0898-0306 in Project Muse

- ↑ Kenneth Bertrams, "Productivite Economique et Paix Sociale au sein du Plan Marshall: Les Limites de l'influence Americaine aupres des Industriels et Syndicats Belges, 1948-1960," [Economic Productivity and Social Peace Within the Marshall Plan: the Limits of American Influence on Belgian Industrialists and Trade Unionists, 1948-60]. Cahiers D'histoire du Temps Présent 2001 (9): 191-235. Issn: 0771-6435

- ↑ John S. Hill, "American Efforts to Aid French Reconstruction Between Lend-Lease and the Marshall Plan." Journal of Modern History 1992 64(3): 500-524. Issn: 0022-2801 in jstor

- ↑ Philippe Mioche, "Le Demarrage de l'economie Française au lendemain de la Guerre," [Restarting the French Economy after the War]. Historiens et Géographes 1998 89(361): 143-156. Issn: 0046-757x

- ↑ Bernadette Whelan, "Ireland, the Marshall Plan, and U.S. Cold War Concerns." Journal of Cold War Studies 2006 8(1): 68-94.

- ↑ Francesca Fauri, "The Role of Fiat in the Development of the Italian Car Industry in the 1950's" Business History Review 1996 70(2): 167-206. in Jstor]

- ↑ David W. Ellwood, "The Propaganda of the Marshall Plan in Italy in a Cold War Context." Intelligence and National Security 2003 18(2): 225-236.

- ↑ Kai R. Pedersen, "Norwegian Business and the Marshall Plan, 1947-1952." Scandinavian Journal of History 1996 21(4): 285-301. Issn: 0346-8755

- ↑ Till Geiger, "Like a Phoenix from the Ashes!? West Germany's Return to the European Market, 1945-58." Contemporary European History 1994 3(3): 337-353. Issn: 0960-7773

- ↑ Andrea Boltho, "Reconstruction after Two World Wars: Why the Differences?" Journal of European Economic History 2001 30(2): 429-456. Issn: 0391-5115

- ↑ Alan S. Milward, "Was the Marshall Plan Necessary?" Diplomatic History 1989 13(2): 231-253.

- ↑ Barry Eichengreen, Marc Uzan, "The Marshall Plan: Economic Effects and Implications for Eastern Europe and the Former USSR," Economic Policy, Vol. 7, No. 14, Eastern Europe (Apr., 1992), pp. 14-75, in JSTOR; J. B. De Long and B. Eichengreen. "The Marshall Plan: History's Most Successful Structural Adjustment Program," in Rudiger Dornbusch, et al eds. Postwar Economic Reconstruction and Lessons for the East Today (1993) pp 189-230 online edition of 1991 version

- ↑ See their article at p. 4-5

- ↑ Michael Cox and Caroline Kennedy-Pipe. "The Tragedy of American Diplomacy? Rethinking the Marshall Plan," Journal of Cold War Studies 7.1 (2005) 97-134