User:Loc Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen Ngoc Bich

User:Loc_Vu-Quoc/Draft:Nguyen_Ngoc_Bich

Introduction

| Nguyễn Ngọc Bích | |

|---|---|

| Born | 18 May 1911 Ben Tre, Vietnam |

| Died | 4 Dec 1966 Thu Duc, Vietnam |

| Occupation | *Engineer

|

| Title | Doctor (medical) |

| Known for | Resistance war, politics |

Nguyễn Ngọc Bích (1911–1966) was a French-educated engineer, a hero in the Vietnamese resistance against the French colonists,[1]:850. Note a French-educated medical doctor, an intellectual and politician, who proposed an alternative viewpoint to avoid the high-casualty, high-cost war between North Vietnam and South Vietnam.[2]

The Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich street in the city of Cần Thơ, Vietnam, was named after him to honor and commemorate his feats (of sabotaging bridges to slow down the colonial French-army advances) and heroism (being on the French most-wanted list,[3]:122 imprisoned, subjected to an "intensive and unpleasant interrogation"[3]:122 that left a mark on his forehead,Note and exiled) during the First Indochina War.

Upon graduating from the École polytechnique (engineering military school under the French Ministry of Armed Forces) and then from the École nationale des ponts et chaussées (civil engineering) in France in 1935,[4] Dr. Bich returned to Vietnam to work for the French colonial government. After World War II, in 1945, he joined the Viet-Minh, and became a senior commander in the Vietnamese resistance movement, and insisted on fighting for Vietnam's independence, not for communism.

SuspectingNote of being betrayed by the Communist factionNote of the Viet-Minh and apprehended by the French forces, he was saved from execution by a campaign for amnesty by his École polytechnique classmates based in Vietnam, mostly high-level officers of the French army,[5]: 299 and was subsequently exiled to France, where he founded with friends and managed the Vietnamese publishing house Minh Tan (in Paris), which published many important works for the Vietnamese literature.Note In parallel, he studied medicine and became a medical doctor. He was highly regarded in Vietnamese politics, and was suggested by the French in 1954 as an alternative to Ngo Dinh Diem as the sixth prime minister of the State of Vietnam under the former Emperor Bao Dai as Head of State,[6]:84 who selected Ngo Dinh Diem as prime minister. While Bich's candidature for the 1961 presidential election in opposition to Diem was, however, declared invalid by the Saigon authorities at the last moment for "technical reasons",[7][4], he was "regarded by many as a possible successor to President Ngo Dinh Diem".[7] Note 1, Note 2

A large majority of the information in this article came from the master document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography,[8] which contains even more information, including primary-source evidence and photos, than presented here.

Important historical events that affected Bich's adult life, together with those mentioned in his 1962 paper (e.g., failed agrarian reform, napalm bombs, famine, conquest for rice, etc.) are summarized, in particular the atmosphere in which Bich had lived for ten years working for the French colonialists (from 1935 to 1945), and the historical conditions that drove this French-educated engineer to become a "Francophile anticolonialist"Note 1, Note 2 and to join the Viet Minh in 1945 (e.g., the French brutal repressions in 1940 and 1945, the power vacuum after the Japanese coup de force in 1945, Ho Chi Minh's call for a general uprising from Tân Trào, the 1945 August Revolution, the Black Sunday on 1945 Sep 2 in Saigon, etc.). The key principle is to summarize a historical event only when it was directly related to Bich's activities. Care is exercised in selecting references and quotations that complement, but not duplicate, other Wikipedia articles at the time of this writing. For example, the history and the general use of napalm bombs, which Bich mentioned in his 1962 article, are not summarized. Regarding the French using American-made napalm bombs in the First Indochina War, well-known battlesNote are also not summarized.

Bao Dai to de Gaulle ❝I beg you to understand that the only means of safeguarding French interests and the spiritual influence of France in Indochina is to recognize the independence of Vietnam unreservedly and to renounce any idea of reestablishing French sovereignty or rule here in any form. . . . Even if you were to reestablish the French administration here, it would not be obeyed, and each village would be a nest of resistance. . . . We would be able to understand each other so easily and become friends if you would stop hoping to become our masters again.❞ --- Bao Dai, message to de Gaulle on 1945 Aug 20

☛ Updated Loc Vu-Quoc (talk) 14:07, 15 May 2024 (CDT) - Started before Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:30, 5 July 2023 (UTC)

First Indochina War

The broader historic events of World War II and the First Indochina War---specifically, the short interwar period between end of the former and the beginning of the later—led to the context in which Nguyen Ngoc Bich fought the French colonists until he was captured. The activities directly or indirectly affected Bich's life by four historic individuals are summarized. French General de Gaulle, by his desire to reconquer Indochina as a French colony, was a main force that led to the First Indochina War, in which Bich fought. Ho Chi Minh, founder and leader of the Viet Minh, called for the general uprising---against the French colonists and the Japanese occupiers---to which Bich responded. US President Franklin Delano Roosevelt ardent anticolonialism could have prevented the two Indochina wars, and changed the course of history. US President Harry Truman was a reason that the First Indochina War is now called the "French-American" War in Vietnamese literature,[9] and through his support for the French war effort supplied napalm bombs, which Bich mentioned in his 1962 paper. The US funded more than 30% of the war cost in 1952 under US President Eisenhower, and "nearly 80%" in 1954 under Truman.Note N.fwc

I AM HERE 24.5.15.

Notes

- Betrayal suspicion: On the betrayal suspicion, Cooper, Chester L. (1970), The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, Dood, Mead & Company, New York. Retrieved on 7 Mar 2023, p.123, wrote: "Whether the Viet Minh had actually betrayed him to French agents is not known for certain, but Bich always suspected that this was how he had been discovered," whereas the assertion that he "was betrayed by his Communist colleagues to the French" was written in the short biography that accompanied Bich's 1962 article, as written in Honey, P.J., ed. (March 1962), "Special Issue on Vietnam", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023. Volume 9. See the Note on The China Quarterly.

- Back to Note.

- Bich's injury: A photo showing the injury mark on the forefront of Dr. Bich as a result of this "intensive and unpleasant interrogation" can be found in Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography.[8]

- Back to Note.

- China Quarterly: The Editorial of The China Quarterly, Volume 9, reads: "Five of our articles are by specialists who have observed the Hanoi regime from a distance. M. Tongas and Mr. Hoang Van Chi are writing on the basis of personal experience. Dr. Bich presents an independent view of the whole Vietnamese situation." This China Quarterly issue contained the articles written by several well-known intellectuals on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (See Philippe Devillers (1920–2016), un secret nommé Viêt-Nam, Mémoires d'Indochine, Internet archived 2022.06.29), P. J. Honey, William Kaye (see e.g., A Bowl of Rice Divided: The Economy of North Vietnam, 1962), Gerard Tongas, among others. See the Editorial and the brief introduction of the contributors.

- Francophile anticolonialists: "French teachings and models over Confucian ones. Some of these teachings were, to say the least, unhelpful to the colonial enterprise. Voltaire's condemnation of tyranny, Rousseau's embrace of popular sovereignty, and Victor Hugo's advocacy of liberty and defense of workers' uprisings turned some Vietnamese into that curious creature found also elsewhere in the empire: the Francophile anticolonialist."[10]:9

- Back to Note.

- (↑ N.fwc) French-war cost: PBS US Involvement in Vietnam Video time 0:11 to 0:32:[11] "In 1952, General Dwight Eisenhower was elected President, in part because he promised to take a tougher stance on communism. That year, American taxpayers were footing more than 30% of the bill for the French war in Vietnam (also called the "French-American" war[9]). Within two years, that number would rise to nearly 80%." To be more precise, the "U.S. aid to the French military effort mounted from $130 million in 1950 to $800 million in 1953."[12]:597 The "United States became France's largest patron, ultimately funding 78 percent of the French war effort in Indochina,"reported historian L.H.T. Nguyen based on the Vietnamese document "Tong ket cuoc khang chien chong thuc dan Phap," Hanoi: Chinh Tri Quoc Gia, 1996.[13]:46

- Minh Tan book list: A list of important books published by Minh Tan can be found in Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography.

- Back to Note.

- Napalm battles: See, e.g., the battle of Vinh Yen (1951), the battle of Na San (1952), the battle of Dien Bien Phu (1954), etc.

- Back to Note.

- Political influence: A direct quote from the brief introduction of the contributors to The China Quarterly, Volume 9, 1962, reads: Dr. Bich's "personal influence upon Cochin Chinese opinion is considerable, and he is regarded by many as a possible successor to President Ngo Dinh Diem".

- Back to Note.

- Primary sources, quotations: See primary sources, extensive notes and quotations in Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography[8] and Notes on Vietnam History.[14]

References

- ↑ Buttinger, Joseph (1967b), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.2, Frederik A. Praegers, New York. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2023

- ↑ Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (March 1962), "Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023, pp. 105–111. See also the contents of Volume 9, which included the articles of many well-known experts on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (see, e.g., his classic 1952 book Histoire du Viet-Nam in Section References and French French Cochinchina, Ref. 40), P. J. Honey, Gerard Tongas (see, e.g, J'ai vécu dans l'Enfer Communiste au Nord Viet-Nam, Debresse, Paris, 1961, reviewed] by P. J. Honey), among others.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Cooper, Chester L. (1970), The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, Dood, Mead & Company, New York. Retrieved on 7 Mar 2023

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (2018), Le Temps des Ancêtres: Une famille vietnamienne dans sa traversée du XXe siècle, L'Harmattan, Paris, France. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023. Preface by historian Pierre Brocheux.

- ↑ Tran-Thi-Lien (2002), Henriette Bui: The narrative of Vietnam's first woman doctor, in Gisele Bousquet and Pierre Brocheux, Viêt Nam Exposé: French Scholarship on Twentieth-Century Vietnamese Society, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 9780472098057, DOI:10.3998/mpub.12124, at 278–309. Google Book (search for "Bui Quang Chieu Ngoc Bich"), accessed 20 May 2023.

- ↑ Langguth, Arthur John (2000), Our Vietnam: The war, 1954–1975, Simon & Schuster, New York. Retrieved on 14 Mar 2023

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Honey, P.J., ed. (March 1962), "Special Issue on Vietnam", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau & Vu-Quoc-Loc (2023), Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography, Internet Archive. Retrieved on 21 Mar 2023, CC-BY-SA 4.0. (Backup copy.) Much of the information in the present article came from this biography, which also contains many relevant and informative photos not displayed here.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Lady Borton (2020), WE NEVER KNEW: Napalm use during Vietnam's French-American War, vietnamnet.vn, May 5.

- ↑ Logevall, Fredrik (2012), Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam, Random House, New York. Retrieved on 12 Apr 2012, 864 pp. Winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize in History: "For a distinguished and appropriately documented book on the history of the United States, Ten thousand dollars ($10,000). A balanced, deeply researched history of how, as French colonial rule faltered, a succession of American leaders moved step by step down a road toward full-blown war" • Winner of the 2013 Francis Parkman Prize from the Society of American Historians • Winner of the 2013 American Library in Paris Book Award • Winner of the Council on Foreign Relations 2013 Gold Medal Arthur Ross Book Award • Finalist for the 2013 Cundill Prize in Historical Literature.

- ↑ US Involvement in Indochina. Retrieved on 2023-12-09, Template:Plain link. Teaching video excerpt from the documentary The Vietnam War, a film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, vol. 3, Charles Scribner's & Sons, 2002. Retrieved on 2024-05-11.

- ↑ The First Vietnam War: Colonial Conflict and the Cold War, Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, 2007.

- ↑ Vu Quoc Loc (2023a), Notes on Vietnam History, Internet Archive. Retrieved on 27 Jun 2023, CC BY-SA 4.0.

NOTE: 24.5.15, The code below not yet processed for this new style.

Second Indochina War

Intellectual and politician

In 1962, as an intellectual in exile in Paris, Dr. Bich published an article, among respected historians at the time such as Philippe Devillers, Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi etc.,Template:Sfn presenting an incisive analysis of the economics and politics of the two Vietnams, and proposed an alternative viewpoint to avoid the Second Indochina War; see Section Peaceful negotiation, an independent viewpoint, where a summary of his article is provided.

Chester L. Cooper described Dr. Bich as one among some "genuine nationalists" living in exile in France in the 1950s:Template:Sfn Template:Blockquote

In Paris, Dr. Bich was a "most popular oppositionist" to Ngo Dinh Diem and his regime, as described in Joseph Buttinger's book: Template:Blockquote

The French suggested Dr. Bich as a serious alternative to Ngo Dinh Diem as prime minister of South Vietnam under Bao Dai in 1954, after the 1954 Geneva Conference: Template:Blockquote

A 1962 peace proposal

Famine

Land-reform failure

Napalm bombs

Neutrality

Economic cooperation

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:44, 28 April 2023 (UTC)

- Citation and summary of Bich's article, which focused on the neutrality of South Vietnam as a solution to avoid the Second Indochina War.

- Quotations from Asselin (2013)Template:Sfn and Nguyen (2012)Template:Sfn regarding neutrality or neutralization of South Vietnam.

- Refer to master biographyTemplate:Sfn for details.

Early life and education

Engineer and doctor Nguyen Ngoc Bich was born on 18 May 1911[lower-alpha 1] in An Hoi village, Bao Huu canton, Bao An district, now in Giong Mong district, Ben Tre province. He was the son of Mr. Nguyen Ngoc Tuong (1881–1951), Cao DaiTemplate:SfnTemplate:Sfn Ban Chinh Dao (Ben Tre), and Ms. Bui Thi Giau.

As a child, he stayed with his father, lived in many places such as Can Tho, Ha Tien, Can Giuoc and mainly studied in Can Giuoc. In 1926, at the age of 15, he went to Saigon to study and graduated with a Baccalaureat at Chasseloup Laubat French School with very high scores, studying abroad in France. In France, he studied and obtained engineering degrees from the École Polytechnique in Paris (he entered in 1931 and graduated in 1933) and later from the École Nationale des Ponts et Chaussées also in Paris. These are 2 prestigious engineering universities in France, as well as in the world so far, especially Polytechnique because the entrance exam is very difficult and is a military school under the tutelage of the French Ministry of the Army, students when graduating have the rank of a military officer and at that time had to work for the government (civil or military) for a period of time.

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:44, 28 April 2023 (UTC)

- Check for WP:NPOV style; rewrite if necessary.

- References

- Refer to master biographyTemplate:Sfn for details.

Life in exile

Back in France, he lived with Dr Henriette Bui Quang Chieu, Vietnam's first female doctor, but the two did not marry because they were relatives (his mother, Bui Thi Giau, was a cousin of Bui Quang Chieu, Henriette Bui's father). Back in France, he founded in Paris Minh TanTemplate:Sfn publishing house ((agents in Vietnam were the two bookstores Truong Thi (Hanoi) and Bich Van Thu Xa (Saigon)) with some friends to publish works of Vietnamese intellectuals to help improve people's knowledge living in Vietnam.

Published books include such as Dao Duy Anh's "Hán-Việt Tự Điển" (Chinese-Vietnamese dictionary) and "Pháp-Việt Tự Điển" (French-Vietnamese dictionary), "French-Vietnamese Scientific Nouns", Hoang Xuan Han's "Danh từ khoa học Pháp-Việt" (Scientific vocabulary French-Vietnamese), "Chinh Phụ ngăm bị khảo" and "La sơn Phu tử", Tran Duc Thao's "Phénoménologie et matérialisme dialectique" (Phenomenology and Dialectical Materialism), doctors Pham Khac Quan and Le Khac Thien's "Danh tử Pháp Việt về thuật ngữ kỹ thuật trong y tế" (French Vietnamese vocabulary on technical terminology in medicine), etc. After graduating from medicine and receiving a doctor's degree, he studied cancer and taught Medical Physics at the Paris Medical School until his death. After he finished composing his Agrégation thesis ("agrégation" (translated into Thạc Sĩ in Vietnamese) is a degree higher than PHD), he could not take the exam because foreigners who want to be enrolled in the exam, must provide a letter of recommendation from their Embassy, at that time the Embassy of the State of Viet Nam with which he refused to have any link. During the French colonial period, French citizenship was given with parsimony to the ones who rendered great service to France and who applied for it. He did not render any service to France, he just had to work as a civil engineer for the colonial government, which was mandatory because he graduated from Ecole Polytechnique.

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:44, 28 April 2023 (UTC)

- Check for WP:NPOV style; rewrite if necessary.

- References

- Refer to master biographyTemplate:Sfn for details.

Engagement in politics

In 1954, before Diem was selected by Bao Dai, according to the books Our Vietnam: The War 1954–1975 by Arthur John LangguthTemplate:Sfn and The Lost Crusade – America in Vietnam by Chester L. Cooper,Template:Sfn he was widely regarded as a possible prime minister of the State of Vietnam.

Along with some Vietnamese in France, he wanted to give the country another way than the one of war: cooperation between North and South that help each other develop to catch up with neighbouring countries and avoid dependence on foreign states: negotiations and economic and trade cooperation while waiting for favourable conditions for the two sides to unite the country. That idea was echoed by him in an article he wrote in the quarterly magazine China Quarterly, March 3–5, 1962. Later, the same idea was proposed by Ho Chi Minh (in 1958 and 1962)[lower-alpha 2] and Ngo Dinh Diem and Ngo Dinh Nhu[lower-alpha 3] (in 1963) but without success. A member of his group went to Geneva (Geneva Conference in 1954) to meet Phan Van Dong. He was invited by Georges Bidault, French Foreign Minister (until June 16, 1954) to meet and an American professor from Washington came to Paris to see him. But at that time the U.S. policy was to eliminate communism, and Pham Van Dong's side paid attention to the planned reunification elections in 1956.

That group of Vietnamese intellectuals—most of whom were professionals trained and residing in France—kept to be discreet at that time and often met at the headquarters of Minh Tan publishing house, which made them called by some the Minh Tan group. The publisher's logo is a pigeon sandwiched in the beak of an olive branch, symbolizing "Peace".

He sent his candidacy for the 1961 South Viet Nam presidential election, with his partner Nguyễn Văn Thoại,[lower-alpha 4] a professor at Collège de France in Paris and a former minister of Ngô Đình Diệm. But his file was dismissed by the Ngo Dinh Diem government because of "technical problems".

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:44, 28 April 2023 (UTC)

- Check for WP:NPOV style; rewrite if necessary.

- References

- Refer to master biographyTemplate:Sfn for details.

End of life

Suffering from throat cancer, he returned to Vietnam in 1966 when he was very severe and died in Thu Duc on 4 Dec 1966.[lower-alpha 1] He was buried in Ben Tre, near the grave of his father Nguyen Ngoc Tuong and his brothers, including his brother martyr Nguyen Ngoc Nhut,Template:Sfn[lower-alpha 5] who was a member of the Southern Administrative Resistance Committee. But the grave is open because Nhut's remains have been moved by the government to a martyr's graveyard in Ben Tre.

☛ NOT DONE, TO ADD: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 16:44, 28 April 2023 (UTC)

- Check for WP:NPOV style; rewrite if necessary.

- References

- Refer to master biographyTemplate:Sfn for details.

Peaceful negotiation

TO REMOVE: Egm4313.s12 (talk) 15:30, 8 April 2023 (UTC)

- This section will be removed, and replace by Section A 1962 peace proposal.

Vietnam-War casualties

How many people died in the Vietnam War? Britannica (accessed on 2023.02.18)

Written and fact-checked by The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

| In 1995 Vietnam released its official estimate of the number of people killed during the Vietnam War: as many as 2,000,000 civilians on both sides and some 1,100,000 North Vietnamese and Viet Cong fighters. The U.S. military has estimated that between 200,000 and 250,000 South Vietnamese soldiers died. The Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, D.C., lists more than 58,300 names of members of the U.S. armed forces who were killed or went missing in action. Among other countries that fought for South Vietnam, South Korea had more than 4,000 dead, Thailand about 350, Australia more than 500, and New Zealand some three dozen. |

The China Quarterly, Vol. 9, Mar 1962

The China Quarterly | Cambridge Core

| The China Quarterly is the leading scholarly journal in its field, covering all aspects of contemporary China including Taiwan. Its interdisciplinary approach covers a range of subjects including anthropology/sociology, literature and the arts, business/economics, geography, history, international affairs, law, and politics. Edited to rigorous standards by scholars of the highest repute, the journal publishes high-quality, authoritative research. International in scholarship, The China Quarterly provides readers with historical perspectives, in-depth analyses, and a deeper understanding of China and Chinese culture. In addition to major articles and research reports, each issue contains a comprehensive Book Review section. |

The China Quarterly: Volume 9 - | Cambridge Core (Mar 1962)

Contributors

Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint

Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (1962), Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint The China Quarterly, Volume 9, March, pp. 105–111. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1017/S030574100002525X

Summary of main points

In 1962, Dr. BichTemplate:Sfn laid out an argument to avoid the subversion war by North Vietnam to conquer rice from South Vietnam to solve its famine problem due to low yields in agricultural production using archaic methods and due to the failed agrarian reform. His main points were (1) South Vietnam should have a truly liberal democratic government, (2) the South should establish commercial relations with the North to help solve the said famine problem, (3) the South should maintain a non-aligned neutrality that would prevent interference from the North, (4) the South would peacefully negotiate with the North toward a progressive reunification. Below is a more detailed summary of his article, looking back from more than 60 years later. As a result, past tense is used in this summary to describe long-past events, instead of the sometimes present tense used in the original article.Template:Sfn The full article translated into French is available in the document Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography.Template:Sfn

| Contrary to the belief of the Western world (that the Vietnamese generally disliked, and had an inferiority complex against, the Chinese), the Vietnamese tended to be too proud of their history and victories against the Chinese and Mongol invaders over the centuries.

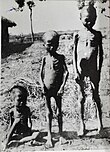

Aware of the Chinese historical "fierce expansionism", an important question for North and South Vietnam was how to safeguard the future of Vietnam as a whole country. While South Vietnam tried to forcibly assimilate Chinese immigrants and their descendants, North Vietnam adopted a "more subtle attitude", moving from "fears" during the Chiang Kai-shek era to "solidarity and friendship" after the communist had won in 1949. The Geneva agreements, while satisfying for China, left the North Vietnamese to be content with the prospect of reunifying with South Vietnam upon an election. After the failure of the agrarian reform, there was a concern of the presence of many Chinese soldiers and civilians in North Vietnam. To keep Chinese economic aid flowing, Ho Chi Minh initially maintained a balance between Peking (Beijing) and Moscow, but subsequently tilted toward Moscow after Peking admitted that it could not help carry out a semi-heavy industrialization. In September 1960, Le Duan, then Secretary-General of the Party, put forward a three-point program: (1) Support Moscow in any Sino-Soviet dispute, (2) Five-year plan (1961–1965) to socialize North Vietnam, (3) Progressive and peaceful reunification of the two Vietnams. With the nomination of Le Duan—who led the struggle for independence in South Vietnam for a long time and knew the South more than anyone else—as First Secretary of the Party, North Vietnam began to undertake the reconquest of the South, with the first step being to eliminate the Ngo Dinh Diem regime and the American influence in the South. There were deeper motives. "The most striking feature of the Vietnamese Communist leadership was its outstanding spirit of realism, even pragmatism." They continuously and critically reexamined facts so that a lesson could be drawn for every action and every happening to avoid past mistakes. By doing so, they tended to imitate or to repeat past actions that were proven successful, and lacked imagination and open-mindedness to create new solutions to tackle new challenges.  French Napalm bomb exploded over Vietminh force. 1953 December. This image during the (French) First Indochina War, conjuring up the horrific destruction of the Napalm on the human flesh,Template:Sfn portended what was to come more than ten years later during the (American) Second Indochina War with even more deadly advanced Napalm technology. For example, they stopped following the advice of Chinese tacticians in launching large-scale mass attacks once many of their soldiers died by French napalm bombs. They switched from the costlier manufacturing of arms to the less expensive manufacturing of hand grenades, which can be used against light battalions to seize their arms. They bred dogs, instead of pigs, as a source of meat since dogs produced two litters of young each year, while pigs produced only one. A deeper motive to swing closer to Moscow was to develop a rapid industrialization to raise the standard of living to avoid complaints about dictatorship and restriction of freedom, and also the "dreaded spectre of becoming a mere satellite state". The targets of the Five-Year Plan were "extremely optimistic". In the old French Indochina, "great leaps forward" in economics were achieved in some sectors, such as a 400% increase in plantation area, 150% increase in the number of workers in industrial establishments, in spite of World War I. Now, there was an abundance of labor due to high unemployment. The planned industrial projects could be completed if foreign aid maintained the same rhythm and agricultural production was adequate. It was doubtful, however, that the target of growing agricultural production by 61% over five years could be achieved due to low yields resulting from the archaic methods of cultivation, the old system of sub-letting land, the difficulty of cultivating new land, the discontent among the peasants, and the disastrous agrarian reforms and its consequence. Hunger had become endemic, and China could not come to the rescue because of her own problems. Rice had to be smuggled from the South to the North. The five-year plan ran a "grave risk of failure" due to lack of food to feed the people in North Vietnam, without an increase in rice supply from South Vietnam, not to mention other unpredictable factors such as floods, droughts, bad weather, etc. The success of the Five-Year Plan would be a primary condition to maintain some independence from Peking, which would exert a greater influence than from Moscow in the case of "necessary and inevitable war", and the North being a satellite of China "would constitute a most serious menace for the South, particularly in time of any major crisis". The reconquest of the South entrusted to Le Duan could then be understood as "a struggle unleashed simply for the purpose of conquering rice", without which the five-year plan most certainly would fail. For many Southerners, their reaction against the Diem regime, rather than the love for Communism, enabled this subversion war to continue. The enormous economic benefit that North Vietnam would harvest from the national reunification was the primary reason for the war. North Vietnam was fighting to secure rice, and thus the war was, from the purely national point of view, a legitimate one. Ngo Dinh Diem on the other hand refused to provide aid to alleviate the famine in the North. The Vietnamese people had for a long time a desire to have a liberal, truly democratic government. and had proven that in the end they would rise time and again to thwart the yoke imposed on them by any foreign power. To avoid such internal war for rice from becoming a proxy war for Moscow, there should be a liberal regime in Saigon that allowed for establishing commercial relations with Hanoi and for a call to stop the fighting. Moreover, a non-aligned political neutrality would prevent interference by North Vietnam in the affairs of South Vietnam. A peaceful and progressive reunification of the two Vietnams could only be achieved through negotiation at a table, and not by arm struggle in the jungle. The South would hope to live side by side peacefully with the North to collaborate in building the common Vietnamese nation, as the alternative would make "reunification" a propaganda that concealed the desire to conquer. |

Publication

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Bich (March 1962), "Vietnam—An Independent Viewpoint", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023, pp. 105–111. See also the contents of Volume 9, which included the articles of many well-known experts on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (see, e.g., his classic 1952 book Histoire du Viet-Nam in Section References and French Cochinchina, Ref. 40), P. J. Honey, Gerard Tongas (see, e.g, J'ai vécu dans l'Enfer Communiste au Nord Viet-Nam, Debresse, Paris, 1961, reviewed] by P. J. Honey), among others.

Timeline

Important historical events in Vietnam and in the world that affected directly or indirectly the life of Dr. Nguyen Ngoc Bich, from his birth in 1911 to his death in 1966.

1911

- MM DD, Nguyen Ngoc Bich was born in LOCATION, Vietnam. Section Early life and education.

1930

- Feb 9-10, Yen Bai mutiny. Brutal repression by the French colonialists. Bich at 19 years old.

1931

- MM DD, began to study at the Ecole Polytechnique, Paris, France. Bich at 20.

- met Henriette Bui.

1933

- graduated from the Ecole Polytechnique. Bich at 22.

- began to study at the Ecole National des Ponts et Chaussees.

Notes OLD

Citations OLD

References OLD

- 151: Memorandum Prepared for the Director of Central Intelligence (McCone), 1963. Retrieved on 15 Mar 2023.

- US Involvement in Indochina. Retrieved on 2023-12-09, Template:Plain link. Teaching video excerpt from the documentary The Vietnam War, a film by Ken Burns and Lynn Novick.

- Charles de Gaulle (1959-1969), Former Presidents of the Republic, 15 November 2018. Retrieved on 13 Jun 2023. Internet archived on 2023.03.28.

- How many people died in the Vietnam War?. Retrieved on 30 Mar 2023. Internet archived on 2023.03.28.

- "Dr. Paul Mus dies; a Yale professor. Southeast Asia authority also taught in France", New York Times, 16 August 1969.

- The Atlantic Conference & Charter, 1941, 1941. Retrieved on 21 Apr 2023. Internet archived 2022.11.15.

- Street-naming plan in Can Tho, Vietnam, with biographies, Appendix 1, 9 Apr 2019. Retrieved on 15 Mar 2023. Internet archived 2023.02.10.

- Asselin, Pierre (2013), Hanoi's Road to War, 1954–1965, University of California Press, California.

- Bartholomew-Feis, Dixee (2006), The OSS and Ho Chi Minh: Unexpected Allies in the War against Japan, University Press of Arkansas, Lawrence, Kansas.

- Bartholomew-Feis, Dixee (2020), The OSS in Vietnam, 1945: A War of Missed Opportunities, The National WWII Museum, New Orleans, Jul 15. Retrieved on 1 Mar 2023. Internet archived on 2023.04.26.

- Brocheux, Pierre (2007), Ho Chi Minh: A Biography, translated by Claire Duiker, Cambridge University Press, New York.

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967a), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.1, Frederik A. Praegers, New York. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2023

- Buttinger, Joseph (1967b), Vietnam: A Dragon Embattled, Vol.2, Frederik A. Praegers, New York. Retrieved on 25 Feb 2023

- Cooper, Chester L. (1970), The Lost Crusade: America in Vietnam, Dood, Mead & Company, New York. Retrieved on 7 Mar 2023

- Colman, Jonathan (2012), "Lost crusader? Chester L. Cooper and the Vietnam War, 1963–68", Cold War History 12 (3): 429–449, DOI:10.1080/14682745.2011.573147.

- Devillers, Philippe (1952), Histoire du Viêt-Nam de 1940 à 1952, Seuil, Paris. See also Philippe Devillers (1920–2016), un secret nommé Viêt-Nam, Mémoires d'Indochine, Internet archived 2022.06.29. Patti (1980), p.542, wrote about Devillers (1952): "The most accurate French account of the period; barring several omissions and minor inaccuracies generally attributable to his sources and to the lack of American documentation, it is by far one of the more reliable histories."

- Encyclopedia of American Foreign Policy, vol. 3, Charles Scribner's & Sons, 2002. Retrieved on 2024-05-11.

- Đoàn-Thêm (1965), Hai Mươi Năm Qua: Việc Từng Ngày, (1945-1964) Template:Bracket, Xuân Thu (1986?), Los Alamitos, California. Template:Plain link (read only, cannot search). Template:Plain link (search only, cannot read).

- Donaldson, Gary (1996), America at War Since 1945: Politics and Diplomacy in Korea, Vietnam, and the Gulf War, Praeger, Westport, Connecticut. Retrieved on 8 Apr 2023

- Fenn, Charles (1973), Ho Chi Minh: A Biographical Introduction, Studio Vista, London. Retrieved on 2023-12-27.

- Fox, Margalit (2005), Chester Cooper, 88, a Player in Diplomacy for Two Decades, Is Dead, Nov 7.

- Gettleman, Marvin E. (1967), A Vietnam Bibliography, Assistant Professor of History, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, with the assistance of Sanford L. Silverman, Liberal Arts Bibliographer. The Libraries, Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn, Oct 19. Internet archived 2022.01.01

- Giniger, Henry (1984), America Inside Out, Close to Events, book review, Oct 14.

- Hammer, Ellen J. (1954), The Struggle for Indochina, Stanford University Press, Stanford, California. Retrieved on 11 Mar 2023.

- Honey, P.J., ed. (March 1962), "Special Issue on Vietnam", The China Quarterly 9. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023. Volume 9 contained the articles written by several well-known intellectuals on Vietnam history and politics such as Bernard B. Fall, Hoang Van Chi, Phillipe Devillers (see French Cochinchina, Ref. 40), P. J. Honey, William Kaye (see e.g., A Bowl of Rice Divided: The Economy of North Vietnam, 1962), Gerard Tongas, among others. See the Editorial and the brief introduction of the contributors.

- Lambert, Bruce (1992), Joseph A. Buttinger, Nazi Fighter And Vietnam Scholar, Dies at 85, Mar 8.

- Lancaster, Donald (1961), The Emancipation of French Indochina, Royal Institute of International Affairs, Oxford University Press, New York; reprinted by Octagon Books, New York, 1975. Retrieved on 11 Mar 2023

- Langguth, Arthur John (2000), Our Vietnam: The war, 1954–1975, Simon & Schuster, New York. Retrieved on 14 Mar 2023

- The First Vietnam War: Colonial Conflict and the Cold War, Harvard University Press, Massachusetts, 2007.

- Logevall, Fredrik (2012), Embers of War: The Fall of an Empire and the Making of America's Vietnam, Random House, New York. Retrieved on 12 Apr 2012, 864 pp. Winner of the 2013 Pulitzer Prize in History: "For a distinguished and appropriately documented book on the history of the United States, Ten thousand dollars ($10,000). A balanced, deeply researched history of how, as French colonial rule faltered, a succession of American leaders moved step by step down a road toward full-blown war" • Winner of the 2013 Francis Parkman Prize from the Society of American Historians • Winner of the 2013 American Library in Paris Book Award • Winner of the Council on Foreign Relations 2013 Gold Medal Arthur Ross Book Award • Finalist for the 2013 Cundill Prize in Historical Literature.

- Marr, David G. (1984), Vietnamese Tradition on Trial, 1920-1945, University of California Press, Berkeley. Retrieved on 2024-05-05.

- Marr, David G. (2013), Vietnam: State, War, and Revolution (1945-1946), University of California Press, Berkeley.

- Nguyen-Hung (2003), Dũng khí Nguyễn Ngọc Nhựt (The Heroic Nguyen Ngoc Nhut), Nam Bộ Nhân Vật Chí (History of notable personalities in South Vietnam), Trẻ (Youth), Ho-Chi-Minh City, Vietnam.

- Nguyen, Lien-Hang T. (2012), Hanoi's War, University of North Carolina Press, Chapel Hill.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (2018), Le Temps des Ancêtres: Une famille vietnamienne dans sa traversée du XXe siècle, L'Harmattan, Paris, France. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023. Preface by historian Pierre Brocheux.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (20 Jul 2021), The basic truths on Caodaism, education.edu.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau (2023), Viet Nam Political History of the Two Wars: Independence War (1858–1954) and Ideological War (1945–1975), Nombre 7, Nîmes, France.

- Nguyen-Ngoc-Chau & Vu-Quoc-Loc (2023), Nguyen Ngoc Bich (1911–1966): A Biography, Internet Archive. Retrieved on 21 Mar 2023, CC-BY-SA 4.0. (Backup copy.) Much of the information in the present article came from this biography, which also contains many relevant and informative photos not displayed here.

- Osborne, Milton (1967), "Viet-Nam: The Search for Absolutes", International Journal 22 (4): 647–654, DOI:10.2307/40200203. Retrieved on 18 Feb 2023.

- Pace, Eric (2001), Ellen Hammer, 79; Historian Wrote on French in Indochina, Mar 26.

- Patti, Archimedes (1980), Why Viet Nam? Prelude to America's Albatross, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 978-0520047839

- Scigliano, Robert (1963), South Vietnam: Nation under Stress, Praeger, New York.

- Stockton, Richard (2022), The True Story Of Phan Thi Kim Phúc, The 'Napalm Girl', edited by Leah Silverman, Dec 25. Internet archived on 2023.03.31.

- Tong, Traci (2018), How the Vietnam War's Napalm Girl found hope after tragedy, The World from PRX, Feb 21. Internet archived on 2023.02.22.

- Tønnesson, Stein (1991), The Vietnamese Revolution of 1945: Roosevelt, Ho Chi Minh and de Gaulle in a world at war, SAGE Publications, London. Retrieved on 2024-05-05. Link to this book at the Norwegian National Library.

- Tønnesson, Stein (2010), Vietnam 1946: How the War Began, University of California Press, Berkeley, California. Retrieved on 2024-05-05.

- Tram-Huong (2003), Đêm trắng của Đức Giáo Tông (Sleepless Night of the Cao Dai Pope), People's Police Publishing House, Vietnam.

- Tran-Thi-Lien (2002), Henriette Bui: The narrative of Vietnam's first woman doctor, in Gisele Bousquet and Pierre Brocheux, Viêt Nam Exposé: French Scholarship on Twentieth-Century Vietnamese Society, University of Michigan Press, ISBN 9780472098057, DOI:10.3998/mpub.12124, at 278–309. Google Book (search for "Bui Quang Chieu Ngoc Bich"), accessed 20 May 2023.

- Vu Quoc Loc (2023a), Notes on Vietnam History, Internet Archive. Retrieved on 27 Jun 2023, CC BY-SA 4.0.

- Vu-Quoc-Loc (2023b), Marco Polo's Caugigu - Phạm Ngũ Lão's Đại Việt - 1285, Internet Archive. Retrieved on 23 Apr 2023, CC-BY-SA 4.0.

- Ward, Geoffrey C. & Ken Burns (2017), The Vietnam War: An Intimate History, Alfred A. Knopf, New York. Retrieved on 2024-05-05.

Gallery

Nguyen Ngoc Bich

Images used to illustrate this article.

First Indochina War

Images used to illustrate this article.

OSS Maj. Archimedes Patti and Vo Nguyen Giap saluted American flag, with a Viet Minh band playing the Star Spangled Banner, 1945 Aug 26, Sunday.

Vo Nguyen Giap gave a welcoming parade to US Maj. Archimedes Patti, head of the US Army intelligence team (OSS), 1945 Aug 26, Sunday.

Ho Chi Minh declared Vietnam independence, 1945 Sep 2.

Ho Chi Minh and Vo Nguyen Giap giving a farewell party to the US Army intelligence team (OSS), 1945.

1945.09.02 Archimedes Patti Operational Priority communication

Ho Chi Minh, Leclerc, Sainteny, 1945 Mar 18

Second Indochina War

Images used to illustrate this article.

Template:Commons category Template:Draft categories

fr:Nguyen Ngoc Bich

vi:Nguyen Ngoc Bich

Template:Drafts moved from mainspace

Cite error: <ref> tags exist for a group named "lower-alpha", but no corresponding <references group="lower-alpha"/> tag was found