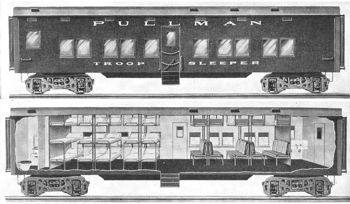

Troop sleeper

A troop sleeper was a railroad passenger car which had been constructed specifically to serve as a "mobile barracks" for transporting troops during wartime over distances sufficient to require overnight accommodations. Pairing the sleepers with troop kitchens and troop hospital cars (when required) allowed part of the trip to be made overnight, reducing the total transit time required while travel efficiency.

History

Background

Between December, 1941 and June, 1945 U.S. railroads carried almost 44 million armed services personnel. As there were not an adequate number of conventional sleeping cars and coaches available to meet the massive need for troop transit created by World War II, in late 1943 the U.S. Office of Defense Transportation contracted with the Pullman Company to build 2,400 troop sleepers, and with American Car and Foundry (ACF) to build 440 troop kitchen cars.[1]

Development

United States Army "Medical Department Kitchen Car" #8762 sits at the Lafayette, Indiana shops of the Monon Railroad on April 17, 1947.

The new rolling stock was either converted from existing boxcars or built from scratch based on Association of American Railroads (AAR) standard 50'-6" single-sheathed steel boxcar designs, and were constructed entirely out of steel with heavily-reinforced ends. In some instances baggage cars were converted into temporary kitchen cars before ACF could complete its order.[2] The cars were painted the standard Pullman Green and affixed with gold lettering. Along the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway's "Surf Line," trains consisting of 10-12 former Southern Pacific-Pacific Electric non-electrified interurban cars, owned by the United States Maritime Commission but bearing ATSF markings, were fitted with conventional knuckle couplers at each end of the trainset and pressed into service to handle the additional passenger loads.[3] Equipped with special Allied Full Cushion high-speed swing-motion trucks, Pullman troop sleepers were designed to be fully-interchangeable with all other passenger equipment. The units came equipped with end doors similar otthose found on standard railway cars, but had no vestibules.[4] Loading and unloading of passengers was accomplished via wide doors positioned on each side at the center of the cars with built-in trap doors and steps. Light and ventilation was provided by ten window units mounted on each side, each equipped with rolling black out shades and wire mesh screens.

Troop sleepers, which were generally intended for use by enlisted personnel, were equipped with bunks stacked 3-high, and slept 29 servicemen plus the Pullman porter. Every passenger was provided with a separate Pullman bed, complete with sheets and pillowcases that were changed daily. The berths were laid out in a cross-wise arrangement that placed the aisle along one side of the car, as opposed to down the center. Though the upper berths were fixed, the middle and lower sections could be reconfigured into seating during the daytime. Weapon racks were provided for each group of berths. Four washstands (two mounted at each end of the car) delivered hot and cold running water. The cars also came outfitted with two enclosed toilets and a drinking water cooler.[5] Troop kitchens, essentially rolling galleys, also joined the consists in order to provide meal service en route (the troops took their meals in their seats or bunks). As the cooking was performed by regular Army cooks, the cars were outfitted with two Army-standard coal-fired ranges. The units were also equipped with a pair of 200-gallon cold water tanks and a 40-gallon hot water tank; supplies were stocked on open shelves with marine-type railings, a bread locker, a large refrigerator, and a series of built-in cabinets and drawers. The cars served approximately 250 men each, and were typically placed inthe middle of the train in order that food could be served from both ends.[6] Troop hospital cars, also based on the troop sleeper carbody, transported wounded servicemen and typically travelled in solid strings on special trains averaging fifteen cars each. Each had 38 berths for patients, 30 of which were arranged in the central section of the car in three tiers on each side. There was also a section with six berths which could be used for isolation cases as well as private compartments for special cases. Each unit was ice air-conditioned and came fitted with a shower room along with a modern kitchen with the latest equipment.[7]

Troop cars saw service though 1947, after which many were sold by the U.S. Army Transportation Corps to the railroads and subsequently converted into mail cars, express service boxcars, or refrigerator cars, while others remained in sleeper configuration for use in maintenance-of-way (MOW) service as bunk cars for the maintenance workers.[8] Subsequent conflicts have not created the need for such an arrangement, partially due to the much smaller level of manpower involved but primarily due to the wider use of aircraft for long-distance transportation of troops.

Preservation

Today, preserved troop sleepers can be seen in several rail museums across the United States.