Malaria

Template:TOC-right Malaria, caused by four species of Plasmodium protozoa and spread by mosquitoes, causes more deaths, worldwide, than any other vector-borne disease. Coping with malaria must be a two-pronged strategy of preventing and treating the disease in humans, and eradicating the disease-carrying mosquito vectors. The World Health Organization considers it the greatest problem among tropical diseases:[1]

- Malaria is both preventable and curable.

- A child dies of malaria every 30 seconds.

- More than one million people die of malaria every year, mostly infants, young children and pregnant women and most of them in Africa

Developed countries cannot be complacent. It has been assessed as a world threat in analysis a U.S. National Intelligence Estimate.

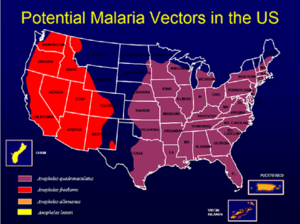

The mosquito vector is present in many parts of the world, and refugees from endemic areas potentially can introduce it, as shown in he U.S. map with areas that have the appropriate mosquitoes. While malaria, in the U.S., there are 1500 cases of malaria annually in the U.S., which could get into the mosquito population.[2] five cases of malaria were diagnosed in 2007, among Burundian refugees who had settled in the state of Washington, in the western United States. [3]

Further, while mosquitoes are the natural vector, malaria certainly can be spread through shared hypodermic needles, either from intravenous drug abuse, or in areas where the healthcare system cannot afford either disposable hypodermics or proper sterilization.

Etiology

The protozoa, of the genus Plasmodium, are carried in the saliva of Anopheles mosquitoes, which reproduce in stagnant water. There are four species: P. falciparum, P. vivax, P. ovale, and P. malariae.

Prevention

Simple mechanical means are the starting point in controlling them: minimizing standing water and using netting. Appropriate insecticide and insect repellents have a role, although resistance to the main insecticides, DDT and pyrethrins, is increasing and there are o immediate alternatives. The basic techniques can be enhanced with :

- Indoor Residual Spraying of long-acting insecticide (IRS)

- Long-Lasting Insecticidal Nets (LLINs).

Integrated Vector Management (IVM) strategies to kill the developing larvae have to be tailored to each environment. These are long-term activities needing long-term funding and political commitment.

While there is no vaccine, chemoprophylaxis can be effective, although, as with the use of anti-malarial drugs to treat active infection, drug resistance is an increasing problem.

The Centers for Disease Control recommend [3] that refugees from sub-Saharan Africa routinely be treated, before leaving Africa, with presumptive artemisinin-based combination therapy (ACT; e.g., artemether-lumefantrine).

Treatment

While malaria is so common, in many areas of Africa, that fever and chills are routinely treated with antimalarial drugs, in the industrialized world, it is principally a disease of travelers. Clinicians encountering possible malaria must maintain a high index of suspicion, and be sure to take travel histories.

Where the disease is not endemic, and the illness is not immediately life-threatening, laboratory diagnosis of the specific Plasmodium species, along with the travel history, will help guide the choice of the appropriate drug treatment. [4] The disease must be reported to local and national public health authorities in non-endemic areas, especially in severe cases where organizations such as the CDC may stock drugs not normally available.

| Plasmodium species | Evaluation | |

|---|---|---|

| P. falciparum | Rapidly progressive illness or death | chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, unless believed resistant; then quinine sulfate plus doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin; or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone). |

| P. vivax | May have dormant state requiring treatment | chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, unless believed resistant; then quinine sulfate plus doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin; or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone). |

| P. ovale | May have dormant state requiring treatment | chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine, unless believed resistant; then quinine sulfate plus doxycycline, tetracycline, or clindamycin; or atovaquone-proguanil (Malarone). |

| P. malariae | chloroquine or hydroxychloroquine |

Mild cases can be treated with oral therapy. The presence of any of the following factors may justify urgent parenteral therapy: who have one or more of the following clinical criteria

- impaired consciousness/coma or repeated generalized convulsions

- severe normocytic anemia

- renal failure

- pulmonary edema

- acute respiratory distress syndrome

- circulatory shock

- acidosis,

- disseminated intravascular coagulation or spontaneous bleeding or hemoglobinuria, *jaundice

- blood parasite load of > 5%

References

- ↑ World Health Organization, Malaria

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control, Malaria

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "Malaria in Refugees from Tanzania – King County, Washington, 2007", Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, August 14, 2008

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control, Treatment: General Approach § Treatment: Uncomplicated Malaria