Phonology of Irish

The phonology of Irish varies from dialect to dialect; there is no standard pronunciation of the language. Therefore, this article focuses on phenomena that pertain generally to most or all dialects, and on the major differences among the dialects.

Irish phonology has been studied as a discipline since the late nineteenth century, with numerous researchers publishing descriptive accounts of dialects from all regions where the language is spoken. More recently, theoretical linguists have also turned their attention to Irish phonology, producing a number of books, articles, and doctoral theses on the topic.

One of the most important aspects of Irish phonology is the fact that almost all consonants appear in pairs, with one member of each pair being 'broad' and the other 'slender'. Broad consonants are velarised, that is, the back of the tongue is pulled back and slightly up in the direction of the soft palate while the consonant is being articulated. Slender consonants are palatalised, which means the tongue is pushed up toward the hard palate during the articulation. The contrast between broad and slender consonants is crucial in Irish, because the meaning of a word can change if a broad consonant is substituted for a slender consonant or vice versa. For example, the only difference in pronunciation between the words bó 'cow' and beo 'alive' is that bó is pronounced with a broad b sound, while beo is pronounced with a slender b sound. The contrast between broad and slender consonants plays a critical role not only in distinguishing the individual consonants themselves, but also in the pronunciation of the surrounding vowels, in the determination of which consonants can stand next to which other consonants, and in the behaviour of words that begin with a vowel.

Irish shares a number of phonological characteristics with its nearest linguistic relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx, as well as with Hiberno-English, the language with which it is most closely in contact.

History of the discipline

Until the end of the nineteenth century, linguistic discussions of Irish focused either on the traditional grammar of the language (issues like the inflection of nouns, verbs and adjectives) or on the historical development of sounds from Proto-Indo-European through Proto-Celtic to Old Irish. The first descriptive analysis of the phonology of an Irish dialect[2] was based on the author's fieldwork in the Aran Islands. This was followed by a phonetic description of the dialect of Meenawannia near Glenties, County Donegal.[3] Alf Sommerfelt published early descriptions of both Ulster and Munster varieties[4] and for the now extinct dialect of South Armagh).[5] The dialect of Dunquin on the Dingle Peninsula has also been described.[6]. From 1944 to 1968, the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies published a series of monographs, each describing the phonology of one local dialect: West Muskerry in County Cork (Ballyvourney, Coolea and vicinity),[7] Cois Fhairrge in Connemara (Barna, Spiddal, Inverin and vicinity),[8] Ring in County Waterford,[9] for Tourmakeady in County Mayo,[10] Teelin in County Donegal,[11] and Erris in County Mayo.[12] More recent descriptive phonology has been published for Rosguill in northern Donegal,[13] Iorras Aithneach in Connemara (Kilkieran and vicinity),[14] and the Dingle Peninsula in County Kerry.[15]

Recent research into the theoretical phonology of Irish followed the principles and practices of The Sound Pattern of English (SPE).[16] Dissertations examining Irish phonology from a theoretical point of view have used Optimality Theory[17] and government phonology.[18]

Consonants

Most dialects of Irish contain at a minimum the consonant phonemes shown in the following chart (see International Phonetic Alphabet for an explanation of the symbols). Symbols appearing in the upper half of each row are velarised or 'broad', while those in the bottom half are palatalised or 'slender'. The consonant /h/ is neither broad nor slender.

| Consonant phonemes |

Labial | Coronal | Dorsal | Glottal | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bilabial | Labio- dental |

Labio- velar |

Dental | Alveolar | Post- alveolar |

Palatal | Velar | |||||||||||

| Plosive | pˠ pʲ |

bˠ bʲ |

t̪ˠ |

d̪ˠ |

tʲ |

dʲ |

c |

ɟ |

k |

ɡ |

||||||||

| Fricative/ Approximant |

fˠ fʲ |

vʲ |

w |

sˠ |

ʃ |

ç |

j |

x |

ɣ |

h | ||||||||

| Nasal | mˠ mʲ |

n̪ˠ |

nʲ |

ɲ |

ŋ |

|||||||||||||

| Tap | ɾˠ ɾʲ |

|||||||||||||||||

| Lateral approximant |

ɫ̪ |

lʲ |

||||||||||||||||

On- and offglides

Broad (velar or velarised) consonants have a noticeable velar offglide (a very short vowel-like sound) before front vowels, which sounds like the English w but made without rounding the lips. The IPA symbol for this sound is [ɰ]. Thus naoi /n̪ˠiː/ 'nine' and caoi /kiː/ 'way, manner' are pronounced [n̪ˠɰiː]) and [kɰiː],[19][20] This velar offglide is labialised (pronounced with lip-rounding, like w) after labial consonants, so buí /bˠiː/ 'yellow' is pronounced [bˠwiː].[21] Similarly, slender (palatal or palatalised) consonants have a palatal offglide (like English y) before back vowels, e.g. tiubha /tʲuː/ "thick" is pronounced [tʲjuː].[22]

When a broad consonant follows a front vowel, there is a very short vowel sound [ə̯]) (called an onglide) just before the consonant, e.g. díol /dʲiːɫ̪/ 'sell' is pronounced [dʲiːə̯ɫ̪/]. Similarly, when a slender consonant follows a back vowel, there is an onglide [i̯] before the consonant, e.g. áit /aːtʲ/ 'place' is pronounced [aːi̯tʲ]),[23] óil /oːlʲ/ 'drinking' (genitive) is pronounced [oːi̯lʲ],[24] meabhair /mʲəuɾʲ/ 'understanding' is [mʲəui̯ɾʲ],[25] dúinn /d̪ˠuːn̠ʲ/ is [d̪ˠuːi̯n̠ʲ].[26]

Allophones

/w/ has two basic allophones: the labiovelar approximant [w]) and the velarised voiced labiodental fricative [vˠ]). The distribution of these allophones varies from dialect to dialect. In Munster generally only [vˠ]) is found,[27] and in Ulster generally only [w].[28] In Connacht [w] is found word-initially before vowels (e.g. bhfuil [wɪlʲ] 'is') and [vˠ] in other positions (e.g. naomh [n̪ˠiːvˠ] 'holy', fómhar [ˈfˠuːvˠəɾˠ] 'autumn', bhrostaigh [ˈvˠɾˠɔsˠt̪ˠə] 'hurried'.[29]

The labiodental fricatives /fˠ, fʲ, vʲ/ as well as the fricative allophone [vˠ] of /w/ have bilabial allophones [ɸˠ, ɸʲ, βˠ, βʲ] in many dialects; the distribution depends partly on environment (bilabials are more likely to be found adjacent to rounded vowels) and partly on the individual speaker.[30]

The alveopalatal stops /tʲ, dʲ/ may be realized as affricates [tɕ, dʑ] in a number of dialects, including Tourmakeady.[31] Erris,[32] and Teelin.[33]

The palatal stops /c, ɟ, ɲ/ may be articulated as true palatals [c, ɟ, ɲ] or as palatovelars [k̟, ɡ˖, ŋ˖].[34]

The phoneme /j/ has three allophones in most dialects: a palatal approximant [j] before vowels besides /iː/ and in at the ends of syllables (e.g. dheas [jasˠ] 'nice', beidh [bʲɛj] 'will be'); a voiced (post)-palatal fricative [ʝ] before consonants (e.g. ghrian [ʝɾʲiən̪ˠ] 'sun'; and an intermediate sound [j˔] (with more frication than [j] but less frication than [ʝ]) before /iː/ (e.g. dhírigh [j˔iːɾʲə]) 'straightened'.[35]

As in English, voiceless stops are aspirated (articulated with a puff of air immediately upon release) at the start of a word, while voiced stops may not be fully voiced but are never aspirated. Voiceless stops are unaspirated after /sˠ/ and /ʃ/ (e.g. scanradh [sˠkauɾˠə][36] 'terror'); however, stops remain aspirated after the clitic is /sˠ/ (e.g. is cam [sˠkʰaum] 'it's crooked'.[37] Several researchers[38] use transcriptions like /sb sd sg xd/, etc., indicating they consider the stops that occur after voiceless fricatives to be devoiced allophones of the voiced stops rather than unaspirated allophones of the voiceless stops, but this is a minority view.

Fortis and lenis sonorants

In Old Irish, the coronal sonorants (those spelled l n r) were divided not only into broad and slender types, but also into fortis and lenis types. The precise phonetic definition of these terms is somewhat vague, but the fortis sounds were probably longer in duration and may have had a larger area of contact between the tongue and the roof of the mouth than the lenis sounds. By convention, the fortis sounds are transcribed with capital letters /L N R/, the lenis with lower case /l n r/. Thus Old Irish had four rhotic phonemes /Rˠ, Rʲ, rˠ, rʲ/, four lateral phonemes /Lˠ, Lʲ, lˠ, lʲ/, and four coronal nasal phonemes /Nˠ, Nʲ, nˠ, nʲ/.[39] Fortis and lenis sonorants contrasted with each other between vowels and word-finally after vowels in Old Irish, for example berraid /bʲeRˠɨðʲ/ 'he shears' vs. beraid /bʲerˠɨðʲ/ 'he may carry'; coll /koLˠ/ 'hazel' vs. col /kolˠ/ 'sin'; sonn /sˠoNˠ/ 'stake' vs. son /sˠonˠ/ 'sound'. [40] Word-initially, only the fortis sounds were found, but they become lenis in environments where morphosyntactically triggered lenition is found: rún /Rˠuːnˠ/ 'mystery' vs. a rún /a rˠuːnˠ/ 'his mystery', lón /Lˠoːnˠ/ 'provision' vs. a lón /a lˠoːnˠ/ 'his provision'.[41]

In the modern language, the four rhotics have been reduced to two in all dialects, /Rˠ, Rʲ, rˠ/ having merged as /ɾˠ/. For the laterals and nasals, some dialects have kept all four distinct, while others have reduced them to three or two distinct phonemes, as summarised in the following table.

| Old Irish | Ulster | Connacht | Munster | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rosguill Lucas (1979) |

Meenawannia Quiggin (1906) |

Mayo Mhac an Fhailigh (1968) |

Connemara de Bhaldraithe (1966) |

1899) | Dingle Peninsula Ó Sé (2000) |

West Muskerry Ó Cuív (1944) | |

| Rˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ | ɾˠ |

| rˠ | |||||||

| Rʲ | |||||||

| rʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ | ɾʲ |

| Lˠ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ | ɫ̪ |

| lˠ | ɫ | ɫ | l | ||||

| lʲ | l | lʲ | lʲ | lʲ | lʲ | lʲ | |

| Lʲ | l̠ʲ | l̠ʲ | l̠ʲ | l̠ʲ | l̠ʲ | ||

| Nˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ | n̪ˠ |

| nˠ | nˠ | nˠ | n | ||||

| nʲ | n | nʲ | nʲ | nʲ | nʲ | nʲ | |

| Nʲ | n̠ʲ | n̠ʲ | n̠ʲ | n̠ʲ | n̠ʲ | nʲ word-initially ɲ elsewhere | |

| Note: l̠ʲ and n̠ʲ are alveolo-palatal consonants. | |||||||

Vowels

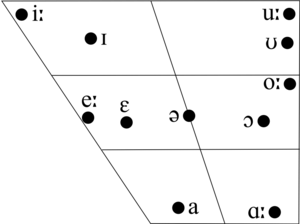

The vowel sounds vary from dialect to dialect, but in general Connacht and Munster at least agree in having the monophthongs /iː/, /ɪ/, /uː/, /ʊ/, /eː/, /ɛ/, /oː/, /ɔ/, /a/, /aː/, and schwa (/ə/), which is found only in unstressed syllables; and the diphthongs /əi/, /əu/, /iə/, and /uə/. The vowels of Ulster Irish are more divergent.

Vowel backness

The backness of vowels (that is, the horizontal position of the highest point of the tongue) depends to a great extent on the quality (broad or slender) of adjacent consonants. Some researchers[44] have argued that [ɪ] and [ʊ] are actually allophones of the same phoneme, as are [ɛ] and [ɔ]. Under this view, these phonemes are not marked at an abstract level as either front vowels or back vowels. Rather, they acquire a specification for frontness or backness from the consonants around them. In this article, however, the more traditional assumption that /ɪ, ʊ, ɛ, ɔ/ are four distinct phonemes will be followed.[45]

Close vowels

The four close vowel phonemes of Irish are the fully close /iː/ and /uː/, and the near-close /ɪ/ and /ʊ/. Their exact pronunciation depends on the quality of the surrounding consonants. /iː/ is realised as a front [iː] between two slender consonants (e.g. tír [tʲiːrʲ] 'country'). Between a slender and a broad consonant, the tongue is retracted slightly from this position (for which the IPA symbol is [i̠ː]), e.g. díol [dʲi̠ːɫ̪] 'sale', caoire [ki̠ːɾʲə] 'berry' (genitive). Between two broad consonants, the tongue is retracted even further, almost to the point of being a central vowel (in IPA, [ïː]): caora [kïːɾˠə] 'sheep'. /uː/ is a fully back [uː] between broad consonants (e.g. dún [d̪ˠuːn̪ˠ] 'fort'), but between a broad and a slender consonant, the tongue is somewhat advanced (IPA [u̟ː]), e.g. triúr [tʲɾʲu̟ːɾˠ] 'three people', súil [sˠu̟ːlʲ] 'eye'. Between two slender consonants it is advanced even further, to a centralised vowel (IPA [üː]): ciúin [cüːnʲ] 'quiet'.

The near-close vowels /ɪ/ and /ʊ/ show a similar pattern. /ɪ/ is realised between slender consonants as a front [i̞], e.g. tigh [tʲi̞ɟ] 'house' (dative). After a slender consonant and before a broad one, it is a near-front [ɪ] giota [ˈɟɪt̪ˠə] 'piece'. After a broad consonant and before a slender one, it is a more retracted [ɪ̈], e.g. tuigeann [ˈt̪ˠɪ̈ɟən̪ˠ] 'understands'. Finally, between two broad consonants it is a central [ɨ̞], e.g. goirt [ɡɨ̞ɾˠtʲ][46] 'salty'. /ʊ/ is a near-back [ʊ] when all adjacent consonants are broad, e.g. dubh [d̪ʊvˠ] 'black', and a more centralised [ʊ̟] after a slender consonant, e.g. giobal [ˈɟʊ̟bˠəɫ̪] 'rag'.

Mid vowels

The realisation of the long close-mid vowels /eː/ and /oː/ varies according to the quality of the surrounding consonants. /eː/ is a front [eː] between two slender consonants (e.g. béic [bʲeːc] 'yell'), a centralised [ëː] between a broad and a slender consonant (e.g. glaoigh [ɡɫ̪ëːɟ] 'call'), and a more open centralised [ɛ̝̈ː] between two broad consonants (e.g. baol [bˠɛ̝̈ːɫ̪] 'danger'. /oː/ ranges from a back [oː] between two broad consonants (e.g. fód [fˠoːd̪ˠ] 'turf') to an advanced [o̟ː] between a broad and a slender consonant (e.g. fóid [fˠo̟ːdʲ] 'turf' (genitive)) to a centralised [öː] between two slender consonants (e.g. ceoil [cöːlʲ] 'music' (genitive)).

The short open-mid vowels also vary depending on their environment. Short /ɛ/ ranges from a front [ɛ̝] between slender consonants (e.g. beidh [bʲɛ̝ɟ] 'will be') to a retracted [ɛ̝̈] between a broad and a slender consonant (e.g. bead [bʲɛ̝̈d̪ˠ] 'I will be', raibh [ɾˠɛ̝̈vʲ] 'was') to a central [ɘ̞] when the only adjacent consonant is broad (e.g. croich [kɾˠɘ̞] 'cross' (dative). Short /ɔ/ between two broad consonants is usually a back [ɔ̝], e.g. cloch [kɫ̪ɔ̝x] 'stone', but it is a centralised [ö] adjacent to nasal consonants and labial consonants, e.g. ansan [ən̪ˠˈsˠön̪ˠ] 'there', bog [bˠöɡ] 'soft'. Between a broad and a slender consonant it is a more open [ɔ̝̈]: scoil [skɔ̝̈lʲ] 'school', deoch [dʲɔ̝̈x] 'drink'.

Unstressed /ə/ is realised as a near-close, near-front [ɪ] when adjacent to a palatal consonant, e.g. píce [ˈpʲiːcɪ] 'pike'. Next to other slender consonants, it is a mid-centralised [ɪ̽], e.g. sáile [ˈsˠaːlʲɪ̽] 'salt water'. Adjacent to broad consonants it is usually a mid central [ə], e.g. eolas [ˈoːɫ̪əsˠ] 'information', but when the preceding syllable contains one of the close back vowels /uː, ʊ/, it is realised as a mid-centralised back [ʊ̽], e.g. dúnadh [ˈd̪ˠuːn̪ˠʊ̽] 'closing', muca [ˈmˠʊkʊ̽].

Open vowels

The realisation of the open vowels varies according to the quality of the surrounding consonants; there is also a significant difference between Munster dialects and Connacht dialects. In Munster, long /aː/ and short /a/ have approximately the same range of realisation: both vowels are relatively back in contact with broad consonants and relatively front in contact with slender consonants. Specifically, long /aː/ in word-initial position and after broad consonants is a back [ɑː], e.g. áit [ɑːtʲ] 'place', trá [t̪ˠɾˠɑː] 'beach'. Between a slender and a broad consonant, it is a retracted front [a̠ː], e.g. gearrfaidh [ˈɟa̠ːɾˠhəɟ] 'will cut', while between two slender consonants it is a fully front [aː], e.g. a Sheáin [ə çaːnʲ] 'John' (vocative). In Dingle, the back allophone is rounded to [ɒː] after broad labials, e.g. bán [bˠɒːn̪ˠ] 'white', while in Ring, rounded [ɒː] is the usual realisation of /aː/ in all contexts except between slender consonants, where it is a centralised [ɒ̈ː] Breatnach (1947: 12–13). Short /a/ between two slender consonants is a front [a], as in gairid [ɟaɾʲədʲ][47] 'short'. Between a broad and a slender consonant, it is in most cases a retracted [a̠], e.g. fear [fʲa̠ɾˠ] 'man', caite [ˈka̠tʲə] 'worn', but after broad labials and /ɫ̪/ it is a centralised front [ä], e.g. baile [bˠälʲə] 'town', loit [ɫ̪ätʲ][48] 'injure'. When it is adjacent only to broad consonants, it is a centralised back [ɑ̈], e.g. mac [mˠɑ̈k] 'son', abair [ɑ̈bˠəɾʲ] 'say'.

In Connacht varieties[49] the allophones of short /a/ are consistently further to the front than the allophones of long /aː/. In Erris, for example, short /a/ ranges from a near-open front vowel [æ] before slender consonants (e.g. sail [sælʲ] 'earwax') to an open [a] after slender consonants (e.g. geal [ɟaɫ] 'bright) to a centralised back [ɑ̈] between broad consonants (e.g. capall [ˈkɑ̈pəɫ̪] 'horse'). Long /aː/, on the other hand, ranges from a back [ɑː] between broad consonants (e.g. bád [bˠɑːd̪ˠ] 'boat') to an advanced back [ɑ̟ː] before slender consonants (e.g. fáil [fˠɑ̟ːlʲ] 'to get') to a centralised back [ɑ̈ː] after slender consonants (e.g. breá [bʲɾʲɑ̈ː] 'fine'). In Tourmakeady,[50] the back allophone is rounded to [ɒː] after broad labials, e.g. bán [bˠɒːn̪ˠ] 'white'. In Connemara, the allophones of /a/ are lengthened in duration, so that only vowel quality distinguishes the allophones of /a/ from those of /aː/.[51]

Diphthongs

The starting point of /əi/ ranges from a near-open central [ɐ] after broad consonants to an open-mid centralised front [ɛ̈] after slender consonants, and its end point ranges from a near-close near-front [ɪ] before slender consonants to a centralised [ɪ̈] before broad consonants.[52] Examples include cladhaire [kɫ̪ɐɪɾʲə] 'rogue', gadhar [gɐɪ̈ɾˠ] 'dog', cill [cɛ̈ɪlʲ] 'church', and leigheas [lʲɛ̈ɪ̈sˠ] 'cure'.

The starting point of /əu/ ranges from a near-open central [ɐ] after broad consonants to an open-mid advanced central [ɜ̟] after slender consonants, and its end point ranges from a near-close near-back [ʊ] before broad consonants to a centralised [ʊ̈] before slender consonants.[53] Examples: bodhar [bˠɐʊɾˠ] 'deaf', feabhas [fʲɜ̟ʊsˠ] 'improvement', labhairt [ɫ̪ɐʊ̈ɾʲtʲ] 'speak', meabhair [mʲɜ̟ʊ̈ɾʲ] 'memory'. In West Muskerry and the Dingle Peninsula, however, the starting point of /əu/ is rounded and further back after broad consonants, e.g. gabhar [gɔʊɾˠ] 'goat'.[54]

The starting point of /iə/ ranges from a close front [i] after slender consonants to a retracted [i̠] after word-initial broad /ɾˠ/ (the only context in which it appears after a broad consonant). Its end point ranges from a mid central [ə] before broad consonants to a close-mid centralised front [ë] before slender consonants.[55] Examples: ciall [ciəɫ̪] 'sense', riamh [ɾˠi̠əvˠ] 'ever', diabhail [dʲiëlʲ] 'devils'.

The starting point of /uə/ is consistently a close back [u] while the end point ranges from [ɐ] to [ɪ̽]:[56]: thuas [huɐsˠ] 'above', uan [uən̪ˠ] 'lamb', buail [bˠuɪ̽lʲ] 'strike'.

Nasalised vowels

In general, vowels in Irish are nasalised when adjacent to nasal consonants. For some speakers, there are reported to be minimal pairs between nasal vowels and oral vowels, indicating that nasal vowels are also separate phonemes. However, the contrast is not robust in any dialect; most published descriptions say that contrastively nasal vowels are present in the speech of only some (usually older) speakers. Potential minimal pairs include those shown in the table below.[57]

| Nasal vowel | Oral vowel | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spelling | Pronunciation | Gloss | Spelling | Pronunciation | Gloss |

| amhras | [ˈə̃ũɾˠəsˠ] | 'doubt' | abhras) | [ˈəuɾˠəsˠ] | 'yarn' |

| áth | [ãː] | 'ford' | ádh | [aː] | 'luck' |

| comhair | [kõːɾʲ] | (in phrase os comhair 'in front of, opposite') | cóir | [koːɾʲ] | 'just, righteous' |

| cumha | [kũː] | 'sorrow' | cú | [kuː] | 'hound' |

| deimhis | [dʲĩːʃ] | 'pairs of shears' | dís | [dʲiːʃ] | 'two people' |

| fómhair | [fˠõːɾʲ] | 'autumn' (genitive) | fóir | [fˠoːɾʲ] | 'boundary, limit' |

| lámha | [ɫ̪ãː] | 'hands' | lá | [ɫ̪aː] | 'day' |

| lámhach | [ɫ̪ãːx] | 'shooting' | lách | [ɫ̪aːx] | 'generous' |

| nimhe | [nʲĩː] | 'poison' (genitive) | ní | [nʲiː] | 'washing' |

| rámha | [ɾˠãː] | 'oar' (genitive) | rá | [ɾˠaː] | 'saying' |

In addition, where a vowel is nasalised because it is adjacent to a nasal consonant, it often retains its nasalisation in related forms where the consonant is no longer nasal. For example, the nasal /m/ of máthair [ˈmãːhəɾʲ] 'mother' is replaced by non-nasal /w/ in the phrase a mháthair [ə ˈwãːhəɾʲ] 'his mother', but the vowel remains nasalised.[58] Similarly, in sneachta [ˈʃnʲãxt̪ˠə] 'snow' the vowel after the /nʲ/ is nasalised, while in an tsneachta [ə ˈtʲɾʲãxt̪ˠə] 'the snow' (genitive), the /nʲ/ is replaced by /ɾʲ/ in some dialects, but the nasalised vowel remains.[59]

Phonotactics

The most interesting aspects of Irish phonotactics revolve around the behaviour of consonant clusters. Here it is important to distinguish between clusters that occur at the beginnings of words and those that occur after vowels, although there is overlap between the two groups.

Word-initial consonant clusters

Irish words can begin with clusters of two or three consonants. In general, all the consonants in a cluster agree in their quality, i.e. all are either broad or slender. Two-consonant clusters consist of an obstruent consonant followed by a liquid or nasal consonant (however, labial obstruents may not be followed by a nasal); examples include bleán /bʲlʲaːn/ 'milking', breá /bʲɾʲaː/ 'fine', cnaipe /ˈkn̪ˠapʲə/ 'button', dlí /dʲlʲiː/ 'law', gnáth /ɡn̪ˠaː/ 'usual', pleidhce /ˈpʲlʲəicə/ 'idiot', slios /ʃlʲɪsˠ/ 'slice', sneachta /ˈʃnʲaxt̪ˠə/ 'snow', tlúth /t̪ˠɫ̪uː/ 'poker', and tnúth /t̪ˠn̪ˠuː/ 'long for'.[60] In addition, /sˠ/ and /ʃ/ may be followed by a voiceless stop, as in sparán /ˈsˠpˠaɾˠaːn̪ˠ/ 'purse' and scéal /ʃceːɫ̪/ 'story'. Further, the cluster /mˠn̪ˠ/ occurs in the word mná /mˠn̪ˠaː/ 'women' and a few forms related to it. Three-consonant clusters consist of /sˠ/ or /ʃ/ plus a voiceless stop plus a liquid. Examples include scliúchas /ˈʃclʲuːxəsˠ/ 'rumpus', scread /ʃcɾʲad̪ˠ/ 'scream', splanc /sˠpˠɫ̪aŋk/ 'flash', spraoi /sˠpˠɾˠiː/ 'fun', and stríoc /ʃtʲɾʲiːk/ 'streak'.

One exception to quality agreement is that broad /sˠ/ is found before slender labials (and for some speakers in Connemara and Dingle before /c/ as well).[61] Examples include: sméara /sˠmʲeːɾˠə/ 'berries', speal /sˠpʲal/ 'scythe', spleách /sˠpʲlʲaːx/ 'dependent', spreag /sˠpʲɾʲaɡ/ 'inspire', scéal /ʃceːɫ̪/ ~ /sˠceːɫ̪/ 'story'.

In the environment of an initial consonant mutation, there is a much wider range of possible onset clusters;[62] for example, in a lenition environment the following occur: bhlas /wɫ̪asˠ/ 'tasted', bhris /vʲɾʲɪʃ/ 'broke', chleacht /çlʲaxt̪ˠ/ 'practiced', chrom /xɾˠɔmˠ/ 'bent', ghreamaigh /ˈjɾʲamˠə/ 'stuck', ghníomhaigh /ˈjnʲiːwə/ 'acted', shleamhnaigh /hlʲəun̪ˠə/ 'slipped', shnámh /hn̪ˠaːw/ 'swam', shroich /hɾˠɪç/ 'reached'. In an eclipsis environment the following are found: mbláth /mˠɫ̪aː/ 'flower', mbliana /ˈmʲlʲiən̪ˠə/ 'years', mbrisfeá /ˈmʲɾʲɪʃhaː/ 'you would break', ndlúth /n̪ˠɫ̪uː/ 'warp', ndroichead /ˈn̪ˠɾˠɔhəd̪ˠ/ 'bridge', ndréimire /ˈnʲɾʲeːmʲəɾʲə/ 'ladder', ngléasfá /ˈɲlʲeːsˠhaː/ 'you would dress', ngreadfá /ˈɲɾʲadhaː/ 'you would leave', ngníomhófá /ˈɲnʲiːwoːhaː/ 'you would act'.

In Donegal, Mayo, and Connemara dialects (but not usually on the Aran Islands), the coronal nasals /nˠ, nʲ/ can follow only /sˠ, ʃ/ respectively in a word-initial cluster. After other consonants, they are replaced by /ɾˠ, ɾʲ/ (Ó Siadhail|Wigger (1975: 116–17), Ó Siadhail (1989: 95)): cnoc /kɾˠʊk/ 'hill', mná /mˠɾˠaː/ 'women', gnaoi /ɡɾˠiː/ 'liking', tnúth /t̪ˠɾˠuː/ 'long for'.

Under lenition, /sˠn̪ˠ, ʃnʲ/ become /hn̪ˠ, hnʲ/ as expected in these dialects, but after the definite article an they become /t̪ˠɾˠ, tʲɾʲ/: sneachta /ʃnʲaxt̪ˠə/ 'snow', shneachta /hnʲaxt̪ˠə/ 'snow' (lenited form), an tsneachta /ə tʲɾʲaxt̪ˠə/ 'the snow' (genitive).

Post-vocalic consonant clusters and epenthesis

Like word-initial consonant clusters, post-vocalic consonant clusters usually agree in broad or slender quality. The only exception here is that broad /ɾˠ/, not slender /ɾʲ/, appears before the slender coronals /tʲ, dʲ, ʃ, nʲ, lʲ/ Ó Sé (2000: 34–36): beirt /bʲɛɾˠtʲ/ 'two people', ceird /ceːɾˠdʲ/ 'trade', doirse /ˈd̪ˠoːɾˠʃə/ 'doors', doirnín /d̪ˠuːɾˠˈnʲiːnʲ/ 'handle', comhairle /ˈkuːɾˠlʲə/ 'advice'.

A cluster of /ɾˠ, ɾʲ/, /ɫ̪, lʲ/, or /n̪ˠ, nʲ/ followed by a labial or dorsal consonant (except the voiceless stops /pˠ, pʲ/, /k, c/) is broken up by an epenthetic vowel /ə/: borb /ˈbˠɔɾˠəbˠ/ 'abrupt', gorm /ˈɡɔɾˠəmˠ/ 'blue', dearmad /ˈdʲaɾˠəmˠəd̪ˠ/ 'mistake', dearfa /ˈdʲaɾˠəfˠə/ 'certain', seirbhís /ˈʃɛɾʲəvʲiːʃ/ 'service', fearg /ˈfʲaɾˠəɡ/ 'anger', dorcha /ˈd̪ˠɔɾˠəxə/ 'dark', dalba /ˈd̪ˠaɫ̪əbˠə/ 'bold', colm /ˈkɔɫ̪əmˠ/ 'dove', soilbhir /ˈsˠɪlʲəvʲəɾʲ/ 'pleasant', gealbhan /ˈɟaɫ̪əwən̪ˠ/ 'sparrow', binb /ˈbʲɪnʲəbʲ/ 'venom', Banba, /ˈbˠan̪ˠəbə/ (a name for Ireland), ainm /ˈanʲəmʲ/ 'name', meanma /ˈmʲan̪ˠəmˠə/ 'mind', ainmhí /ˈanʲəvʲiː/ 'animal'.[63]

There is no epenthesis, however, if the vowel preceding the cluster is long or a diphthong: fáirbre /ˈfˠaːɾʲbʲɾʲə/ 'wrinkle', téarma /ˈtʲeːɾˠmˠə/ 'term', léargas /ˈlʲeːɾˠɡəsˠ/ 'insight', dualgas /ˈd̪ˠuəɫ̪ɡəsˠ/ 'duty'. There is also no epenthesis into words that are at least three syllables long: firmimint /ˈfʲɪɾʲmʲəmʲənʲtʲ/ 'firmament', smiolgadán /ˈsˠmʲɔɫ̪ɡəd̪ˠaːn̪ˠ/ 'throat', caisearbhán /ˈkaʃəɾˠwaːn̪ˠ/ 'dandelion', Cairmilíteach /ˈkaɾʲmʲəlʲiːtʲəx/ 'Carmelite'.

Phonological processes

Vowel-initial words

Vowel-initial words in Irish exhibit behaviour that has led linguists to suggest that the vowel sound they begin with on the surface is not, at a more abstract level, actually the first sound in the word. Specifically, when a clitic ending in a consonant precedes a word beginning with the vowel, the consonant of the clitic surfaces as either broad or slender, depending on the specific word in question. For example, the n of the definite article an 'the' is slender before the word iontais 'wonder' but broad before the word aois 'age': an iontais /ənʲ ˈiːn̪ˠt̪ˠəʃ/ 'the wonder' (genitive) vs. an aois /ən̪ˠ ˈiːʃ/ 'the age'.[64]

One analysis of these facts[65] is that vowel-initial words actually begin, at an abstract level of representation, with a kind of empty consonant that consists of nothing except the information 'broad' or 'slender'. Another analysis is that vowel-initial words, again at an abstract level, all begin with one of two semivowels, one triggering palatalisation and the other triggering velarisation of a preceding consonant.[66]

Lengthening before fortis sonorants

Where reflexes of the Old Irish fortis sonorants appear in syllable-final position (in some cases, only in word-final position), they trigger a lengthening or diphthongisation of the preceding vowel in most dialects of Irish.[67] The details vary from dialect to dialect.

In Donegal and Mayo, lengthening is found only before rd, rl, rn, before rr (except when a vowel follows), and in a few words also before word-final ll.[68] For example: barr /bˠaːɾˠ/ 'top', ard /aːɾˠd̪ˠ/ 'tall', orlach /ˈoːɾˠɫ̪ax/ 'inch', tuirne /ˈt̪uːɾˠn̠ʲə/ 'spinning wheel', thall /haːɫ̪/ 'yonder'.

In Connemara,[69] the Aran Islands,[70] and Munster,[71] lengthening is generally found not only in the environments listed above, but also before nn (unless a vowel follows) and before m and ng at the end of a word. For example, the word poll 'hole' is pronounced /pˠəuɫ̪/ in all of these regions, while greim 'grip' is pronounced /ɟɾʲiːmʲ/ in Connemara and Aran and /ɟɾʲəimʲ/ in Munster.

Because in many cases vowels behave differently before broad sonorants than before slender ones, and because there is generally no lengthening (except by analogy) when the sonorants are followed by a vowel, there is a variety of vowel alternations between different related word forms. For example, in Dingle ceann 'head' is pronounced /cəun̪ˠ/ with a diphthong, but cinn (the genitive singular of the same word) is pronounced /ciːnʲ/ with a long vowel, while ceanna (the plural, meaning 'heads') is pronounced /ˈcan̪ə/ with a short vowel.[72]

This lengthening has received a number of different explanations within the context of theoretical phonology. All accounts agree that some property of the fortis sonorant is being transferred to the preceding vowel, but the details about what property that is vary from researcher to researcher. One argument is that the fortis sonorant is tense (a term only vaguely defined in phonetics) and that this tenseness is transferred to the vowel, where it is realised phonetically as vowel length and/or diphthongisation.[73] Another argument holds that the triggering consonant is underlying associated with a unit of 'syllable weight' called a mora; this mora then shifts to the vowel, creating a long vowel or a diphthong.[74] Based on this, the fortis sonorants could have an advanced tongue root (that is, the bottom of the tongue is pushed upward during articulation of the consonant) and that diphthongisation is an articulatory effect of this tongue movement.[75]

Devoicing

Where a voiced obstruent or /w/ comes into contact with /h/, the /h/ is absorbed into the other sound, which then becomes voiceless (in the case of /w/, devoicing is to /fˠ/). Devoicing is found most prominently in the future of first conjugation verbs (where the /h/ sound is represented by the letter f) and in the formation of verbal adjectives (where the sound is spelt th). For example, the verb scuab /sˠkuəbˠ/ 'sweep' ends in the voiced consonant /bˠ/, but its future tense scuabfaidh /ˈsˠkuəpˠəɟ/ 'will sweep' and verbal adjective scuabtha /ˈsˠkuəpˠə/ 'swept' have the voiceless consonant /pˠ/.[76]

Sandhi

Irish exhibits a number of external sandhi effects, i.e. phonological changes across word boundaries, particularly in rapid speech. The most common type of sandhi in Irish is assimilation, which means that a sound changes its pronunciation in order to become more similar to an adjacent sound.

One type of assimilation in Irish is found when a coronal consonant (one of d, l, n, r, s, t) changes from being broad to being slender before a word that begins with a slender coronal consonant, or from being slender to being broad before a word that begins with a broad coronal consonant. For example, feall /fʲaɫ̪/ 'deceive' ends with a broad ll, but in the phrase d'fheall sé orm [dʲal̠ʲ ʃə ɔɾˠəmˠ] 'it deceived me' the ll has become slender because the following word, sé, starts with a slender coronal consonant.[77]

The consonant n may also assimilate to the place of articulation of a following consonant, becoming labial before a labial consonant, palatal before a palatal consonant, and velar before a velar consonant.[78] For example, the nn of ceann /can̪ˠ/ 'one' becomes [mˠ]) in ceann bacach [camˠ ˈbˠakəx]) 'a lame one' and [ŋ]) in ceann carrach [caŋ ˈkaɾˠəx]) 'a scabbed one'.

Finally, a voiced consonant at the end of a word may become voiceless when the next word begins with a voiceless consonant,[79] as in lúb sé [ɫ̪uːpˠ ʃeː]) 'he bent', where the b sound of lúb /ɫ̪uːbˠ/ 'bent' has become a p sound before the voiceless s of sé.

Stress

General facts of stress placement

An Irish word normally has only one stressed syllable, namely the first syllable of the word.[80] Examples include d'imigh [ˈdʲɪmʲiː] 'left' (past tense of leave) and easonóir [ˈasˠən̪ˠoːɾʲ] 'dishonour' de Búrca (1958: 74–75). However, certain words, especially adverbs and loanwords, have stress on a noninitial syllable, e.g. amháin [əˈwaːnʲ] 'only', tobac [təˈbak] 'tobacco'.

In most compound words, primary stress falls on the first member and a secondary stress (marked with [ ˌ ])) falls on the second member, e.g. lagphórtach [ˈɫ̪agˌfˠɔɾˠt̪ˠəx] 'spent bog'. Some compounds, however, have primary stress on both the first and the second member, e.g. deargbhréag [ˈdʲaɾˠəgˈvʲɾʲeːg] 'a terrible lie'.

In Munster, stress is attracted to a long vowel or diphthong in the second or third syllable of a word, e.g. cailín [kaˈlʲiːnʲ] 'girl', achainí [axəˈnʲiː] 'request'.[81]

In the now extinct accent of East Mayo, stress was attracted to a long vowel or diphthong in the same way as in Munster; in addition, stress was attracted to a short vowel before word-final ll, m, or nn when that word was also final in its utterance.[82] For example, capall 'horse' was pronounced [kaˈpˠɞɫ̪] in isolation or as the last word of a sentence, but as [ˈkapˠəɫ̪] in the middle of a sentence.

The nature of unstressed vowels

In general, short vowels are all reduced to schwa ([ə]) in unstressed syllables, but there are some exceptions. In Munster, if the third syllable of a word is stressed and the preceding two syllables are short, the first of the two unstressed syllables is not reduced to schwa; instead it receives a secondary stress, e.g. spealadóir [ˌsˠpʲaɫ̪əˈd̪ˠoːɾʲ] 'scythe-man'.[83] Also in Munster, an unstressed short vowel is not reduced to schwa if the following syllable contains a stressed [iː] or [uː], e.g. ealaí [aˈɫ̪iː] 'art', bailiú [bˠaˈlʲuː] 'gather'.[84] In Ulster, long vowels in unstressed syllables are shortened but are not reduced to schwa, e.g. cailín [ˈkalʲinʲ] 'girl', galún [ˈgaɫunˠ] 'gallon'.[85]

Processes relating to /x/

The voiceless velar fricative /x/, spelt ch, is associated with some unusual patterns in many dialects of Irish. For one thing, its presence after the vowel /a/ triggers behavior atypical of short vowels; for another, /x/ and its slender counterpart /ç/ interchange with the voiceless glottal fricative /h/ in a variety of ways, and can sometimes be deleted altogether.

Behaviour of /ax/

In Munster, stress is attracted to /a/ in the second syllable of a word if it is followed by /x/, provided the first syllable (and third syllable, if there is one) contains a short vowel.[86] Examples include bacach [bˠəˈkax] 'lame' and slisneacha [ʃlʲəˈʃnʲaxə] 'chips'. However, if the first or third syllable contains a long vowel or diphthong, stress is attracted to that syllable instead, and the /a/ before /x/ is reduced to [ə] as normal, e.g. éisteacht [ˈeːʃtʲəxt̪ˠ] 'listen', moltachán [ˌmˠɔɫ̪həˈxaːn̪ˠ].[87] 'wether'.[88] In Ulster, unstressed [a] before [x] is not reduced to schwa, e.g. eallach [ˈaɫ̪ax] 'cattle'.[89]

Interaction of /x/ and /ç/ with /h/

In many dialects of Irish, the voiceless dorsal fricatives /x/ and /ç/ alternate with /h/ under a variety of circumstances. For example, /h/ is replaced by /ç/ before back vowels, e.g. thabharfainn /ˈçuːɾˠhən̠ʲ/[90] 'I would give', sheoil /çoːlʲ/ 'drove'.[91] In Munster, /ç/ becomes /h/ after a vowel, e.g. fiche /fʲɪhə/ 'twenty'.[92] In Ring, /h/ becomes /x/ at the end of a monosyllabic word, e.g. scáth /sˠkaːx/ 'fear'.[93] In some Ulster dialects, such as that of Tory Island, /x/ can be replaced by /h/, e.g. cha /ha/ 'not', and can even be deleted word-finally, as in santach /ˈsˠan̪ˠt̪ˠah ~ ˈsˠan̪ˠt̪ˠa/ 'greedy'.[94] In other Ulster dialects, /x/ can be deleted before /t̪ˠ/ as well, e.g. seacht [ʃat̪ˠ] 'seven'.[95]

Samples

The following table shows some sample sentences from the Aran dialect.[96]

| vʲiː ʃeː əɟ ˈafˠəɾˠk əˈmˠax asˠ ə ˈwɪn̠ʲoːɡ nuəɾʲ ə vʲiː ˈmʲɪʃə ɡɔl haɾˠt̪ˠ | Bhí sé ag amharc[97] amach as an bhfuinneog nuair a bhí mise ag dul thart. | He was looking out the window when I went past. |

| n̠ʲiː ˈɛcətʲ ʃeː pˠəuɫ̪ hɾʲiː ˈdʲɾʲeːmʲɾʲə | Ní fheicfeadh sé poll thrí dréimire. | He wouldn't see a hole through a ladder (i.e. he's very near-sighted). |

| t̪ˠaː mʲeː fʲlɔx hɾʲiːdʲ əsˠ hɾʲiːdʲ | Tá mé fliuch thríd is thríd. | I am wet through and through. |

| hʊɡ ʃeː klɔx woːɾ ˈaɡəsˠ xa ʃeː lɛʃ ə ˈwɪn̠ʲoːɡ iː | Thug sé cloch mhór agus chaith sé leis an bhfuinneog í. | He took a large stone and he threw it against the window. |

| ˈhaːnəɟ ʃeː əʃˈtʲax aɡəsˠ kuːx əɾʲ | Tháinig sé isteach agus cuthach air. | He came in in a rage. |

| ―əɾˠ iːk ʃɪbʲ ˈmˠoːɾˠaːn əɾʲ ə mˠuːn ―ɡə ˈdʲɪvʲən dʲiːk sˠə ˈɫ̪əiəd̪ˠ ə wɪl aːn̪ˠ jɪ |

―Ar íoc sibh[98] mórán ar an móin? ―Go deimhin d'íoc is an laghad a bhfuil ann dhi. |

―Did you pay much for the turf? ―We certainly did, considering how little there is of it. |

| ˈtʲaɡəmʲ aːn̪ˠ xɪlə ɫ̪aː sˠəsˠ ˈmʲɪnəc n̪ˠax mʲiən̪ˠ ˈmˠoːɾˠaːn ˈfˠaːl̠ʲtʲə ɾˠuːmˠ | Tagaim[99] ann chuile lá is is minic nach mbíonn mórán fáilte romham. | I come there every day but often I'm not very welcome. |

| t̪ˠaː mʲeː ˈklɪʃtʲaːl ə ɡɔl haɾˠəmˠ ɡə mʲəi ˈsˠavˠɾˠə fʲlɔx sˠə ˈmʲliənə aɡən̠ʲ aɡəsˠ ˈçiːt̪ˠəɾˠ ɣɔmˠ pʲeːn ɡəɾˠ ˈaʃtʲəx ə ʃceːl eː ʃɪn | Tá mé ag cloisteáil ag dul tharam go mbeidh samhradh fliuch sa mbliana againn, agus chítear[100] dhom féin[101] gur aisteach an scéal é sin. | I have heard tell that we'll have a wet summer this year, but it seems to me that that story is strange. |

| wɪl nə ˈfˠat̪ˠiː xoː mˠasˠ d̪ˠuːɾʲtʲ ʃeː | An bhfuil na fataí chomh maith is dúirt sé? | Are the potatoes as good as he said? |

| ə ˈɣeːlɟə ˈɫ̪əuɾˠiːɾˠ ə ˈɡuːɟə mˠuːn n̠ʲiː ˈhɔnən̪ˠ iː sˠə ˈɣeːlɟə ˈʃaɡən̠ʲə | An Ghaeilge a labhraítear[102] i gCúige Mumhan, ní hionann í is an Ghaeilge seo againne. | The Irish spoken in Munster isn't the same as our Irish. |

Comparison with other languages

Scottish Gaelic and Manx

Many of the phonological processes found in Irish are also found in its nearest relatives, Scottish Gaelic and Manx. For example, both languages contrast 'broad' and 'slender' consonants, but only at the coronal and dorsal places of articulation; both Scottish Gaelic and Manx have lost the distinction in labial consonants. The change of /kn̪ˠ gn̪ˠ mn̪ˠ/ etc. to /kɾˠ gɾˠ mɾˠ/ etc. is found in Manx and in most Scottish Gaelic dialects. Evidence from written manuscripts suggests it had begun in Scottish Gaelic as early as the sixteenth century and was well established in both Scottish Gaelic and Manx by the late seventeenth to early eighteenth century. Lengthening or diphthongisation of vowels before fortis sonorants is also found in both languages.[103] The stress pattern of Scottish Gaelic is the same as that in Connacht and Ulster Irish, while in Manx, stress is attracted to long vowels and diphthongs in non-initial syllables, but under more restricted conditions than in Munster.[104] Manx and many dialects of Scottish Gaelic also share with Ulster Irish the property of not reducing unstressed /a/ to [ə] before /x/.[105]

Hiberno-English

Irish phonology has had a significant influence on the phonology of Hiberno-English.[106] For example, most of the vowels of Hiberno-English (with the exception of /ɔɪ/) correspond to vowel phones (which may or may not be phonemes) of Irish. The Irish stops /t̪ˠ/ and /d̪ˠ/ have been taken over (though without distinctive velarisation) into Hiberno-English as common realisations of the English phonemes /θ/ and /ð/. Hiberno-English also allows /h/ to appear in positions where it is permitted in Irish but excluded in other English dialects, such as before an unstressed vowel (e.g. Haughey ˈ[hɒhi]) and at the end of a word (e.g. McGrath [məˈgɹæh]). Another feature of Hiberno-English phonology probably taken over from Irish is epenthesis in words like film [ˈfɪləm] and form [ˈfɔɹəm].

Footnotes

- ↑ Finck (1899).

- ↑ Finck (1899).

- ↑ Quiggin (1906); for a predominantly historical account, but with some description of modern dialects, see also Pedersen (1909).

- ↑ Sommerfelt (1922) and Sommerfelt (1965) for the village of Torr in Gweedore; Sommerfelt (1927) for Munster.

- ↑ Sommerfelt (1929).

- ↑ Sjoestedt (1931)

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966): first published 1945.

- ↑ Breatnach (1947).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958).

- ↑ Wagner (1959).

- ↑ Mhac an Fhailigh (1968).

- ↑ Lucas (1979).

- ↑ Ó Curnáin (1996).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000).

- ↑ i.e. Chomsky & Halle (1968) was used by Ó Siadhail & Wigger (1975); this work formed the basis of the phonology sections of Ó Siadhail (1989).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1991); Green (1997).

- ↑ Cyran (1997); Bloch-Rozmej (1998).

- ↑ Sjoestedt (1931: 19).

- ↑ Sutton (1993).

- ↑ Sutton (1993); Quiggin (1906: 76).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 11).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 11); de Bhaldraithe (1966: 43).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 59).

- ↑ Mhac an Fhailigh (1968: 46).

- ↑ Sommerfelt (1922: 150).

- ↑ Sjoestedt (1931: 28–29)

- ↑ Quiggin (1906: 74–76).

- ↑ Finck (1899: 64–67); de Bhaldraithe (1966: 30–31).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 31–32).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 24–25).

- ↑ Mhac an Fhailigh (1968: 36–37).

- ↑ Wagner (1959: 9–10).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 14–15, 18).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 39–40); Ó Cuív (1944: 42–43); de Bhaldraithe (1966: 34); Mhac an Fhailigh (1968: 34–35).

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt scamhradh; see orthography of Irish.

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 33, 76).

- ↑ e.g. Ó Cuív (1944); Wagner (1959); de Bhaldraithe (1966); Mhac an Fhailigh (1968); Ó Sé (2000).

- ↑ McCone (1994: 90).

- ↑ Quin (1975: 4–5).

- ↑ Quin (1975: 8).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 7).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 13).

- ↑ e.g. Ó Siadhail & Wigger (1975: 80–82); Ó Siadhail (1989: 35–37); Ní Chiosáin (1994).

- ↑ The descriptions of the allophones in this section come from Ó Sé (2000: 20–24); the pronunciations therefore reflect the Munster accent of the Dingle Peninsula. Unless otherwise noted, however, they largely hold for other Munster and Connacht accents as well.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt guirt.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt geairid.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt lait.

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 12–14); de Búrca (1958: 13–14); Mhac an Fhailigh (1968: 13–16).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 13).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 12–13).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 23–24).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 24–25).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 29); Ó Sé (2000: 24).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 24).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 25).

- ↑ Quiggin (1906: 65); Sjoestedt (1931: 68); Ó Cuív (1944: 54); Ó Sé (2000: 25).

- ↑ Quiggin (1906: 65).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 46).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1999).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 106); Ó Sé (2000: 31).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1999); Ó Sé (2000: 33).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1999).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1991: 80–82).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1991: 83).

- ↑ Ó Siadhail & Wigger (1975: 98–99); Ó Siadhail (1989: 64–65).

- ↑ O'Rahilly (1932: 49–52); Ó Siadhail & Wigger (1975: 89–94); Ó Siadhail (1989: 49–50); Carnie (2002).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 132–34); Mhac an Fhailigh (1968: 163–64); Evans (1969: 127); Ó Baoill (1996: 16).

- ↑ de Bhaldraithe (1966: 109–12).

- ↑ Finck (1899).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 142–44); Ó Cuív (1944: 121–23).

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 40–42).

- ↑ Ó Siadhail & Wigger (1975: 89–90). Repeated in Ó Siadhail (1989: 48–50).

- ↑ Ní Chiosáin (1991: 188–95).

- ↑ Carnie (2002).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 137–38).

- ↑ Quiggin (1906: 146–50).

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 65–68).

- ↑ Finck (1899: 123–124).

- ↑ In IPA transcription, a stressed syllable is marked with the symbol [ ˈ ]) to the left of the syllable.

- ↑ Ó Sé (2000: 46–47).

- ↑ Lavin (1957); Dillon (1973); Green (1997: 86–90).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 67).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 105).

- ↑ Ó Dochartaigh (1987: 19 ff.); Hughes (1994: 626–27).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 66).

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt molthachán.

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 66).

- ↑ Quiggin (1906: 9).

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt thiúrfainn.

- ↑ de Búrca (1958: 129–30).

- ↑ Ó Cuív (1944: 117–18).

- ↑ Breatnach (1947: 137).

- ↑ Hamilton (1974: 152).

- ↑ Ó Searcaigh (1925: 136).

- ↑ Finck (1899: II.1–2).

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt afarc.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt sib.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt teagaim.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt chíotar.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt péin.

- ↑ Pronounced as if spelt labhraíthear.

- ↑ O'Rahilly (1932: 22-23; 49–52).

- ↑ O'Rahilly (1932: 113–115); Green (1997: 90–93).

- ↑ O'Rahilly (1932: 110–12).

- ↑ Wells (1982: 417–50).

References

- Bloch-Rozmej A (1998) Elements Interactions in Phonology: a Study in Connemara Irish. PhD dissertation, Catholic University of Lublin. ISBN 8322806418.

- Breatnach RB (1947) The Irish of Ring, Co. Waterford. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0901282502.

- Carnie A (2002) 'A note on diphthongization before tense sonorants in Irish: an articulatory explanation'. Journal of Celtic Linguistics 7: 129–148.

- Cyran E (1997) 'Resonance elements in phonology: a Study in Munster Irish. PhD dissertation, Catholic University of Lublin. ISBN 8386239417.

- de Bhaldraithe T (1966) The Irish of Cois Fhairrge, Co. Galway. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. 2nd edition. ISBN 0901282510.

- de Búrca S (1958) The Irish of Tourmakeady, Co. Mayo. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0901282499.

- Dillon M (1973) 'Vestiges of the Irish dialect of East Mayo'. Celtica 10: 15–21.

- Evans E (1969) 'The Irish dialect of Urris, Inishowen, Co. Donegal'. Lochlann 4: 1–130.

- Finck FN (1899) Die araner mundart. Marburg: N. G. Elwert.

- Green A (1997) 'The prosodic structure of Irish, Scots Gaelic, and Manx'. PhD dissertation, Cornell University.

- Hamilton JN (1974) 'A phonetic study of the Irish of Tory Island, County Donegal'. Queen's University of Belfast.

- Hughes A (1994) Gaeilge Uladh. In McCone K, McManus D, Ó Háinle C, Williams N & Breatnach L (eds) Stair na Gaeilge in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta. Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp.611-660. ISBN 0901519901.

- Lavin TJ (1957) 'Notes on the Irish of East Mayo: 1'. Éigse 8: 309–321.

- Lucas LW (1979) 'Grammar of Ros Goill Irish, County Donegal'. Queen's University of Belfast.

- McCone K (1994) An tSean-Ghaeilge agus a réamhstair. In McCone K, McManus D, Ó Háinle C, Williams N & Breatnach L (eds) Stair na Gaeilge in ómós do Pádraig Ó Fiannachta. Maynooth: Department of Old Irish, St. Patrick's College. pp.61-219.

- Mhac an Fhailigh E (1968) 'The Irish of Erris, Co. Mayo'. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0901282022.

- Ní Chasaide A (1999) Irish. In Handbook of the International Phonetic Association. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press pp.111–116. ISBN 0521637511.

- Ní Chiosáin M (1991) 'Topics in the phonology of Irish'. PhD dissertation, University of Massachusetts Amherst.

- Ní Chiosáin M (1994) Vowel features and underspecification: evidence from Irish. In Dressler WU, Prinzhorn M & Rennison JR Phonologica 1992: Proceedings of the 7th International Phonology Meeting, Krems, Austria. Turin: Rosenberg & Sellier. pp.157–164. ISBN 8870116115.

- Ní Chiosáin M (1999) Syllables and phonotactics in Irish. In van der Hulst H & Ritter NA The syllable: Views and Facts. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter. pp.551–575. ISBN 3110162741.

- Ó Baoill DP (1996) 'An Teanga Bheo: Gaeilge Uladh'. Dublin: Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0946452857.

- Ó Cuív B (1944) 'The Irish of West Muskerry, Co. Cork'. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0901282529.

- Ó Curnáin B (1996) 'Aspects of the Irish of Iorras Aithneach, Co. Galway'. PhD dissertation, University College Dublin.

- Ó Dochartaigh C (1987) 'Dialects of Ulster Irish'. Belfast: Institute of Irish Studies, Queen's University of Belfast. ISBN 0853892962.

- O'Rahilly TF (1932) Irish Dialects Past and Present. Dublin: Browne & Nolan. Reprinted 1972 by the Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies, ISBN 0901282553.

- Ó Sé D (2000) 'Gaeilge Chorca Dhuibhne'. Dublin: Institiúid Teangeolaíochta Éireann. ISBN 0946452970.

- Ó Searcaigh S (1925). Foghraidheacht Ghaedhilge an Tuaiscirt. Belfast: Browne & Nolan.

- Ó Siadhail M (1989) Modern Irish: Grammatical Structure and Dialectal Variation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521371473.

- Ó Siadhail M & Wigger A (1975) 'Córas fuaimeanna na Gaeilge'. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 0901282642.

- Pedersen H (1909) Vergleichende Grammatik der keltischen Sprachen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 3525261195.

- Quiggin EC (1906) A Dialect of Donegal: Being the Speech of Meenawannia in the Parish of Glenties. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Quin EG (1975) Old-Irish Workbook. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 0901714089.

- Sjoestedt M-L (1931) Phonétique d'un parler irlandais de Kerry. Paris: Leroux.

- Sommerfelt A (1922) The Dialect of Torr, Co. Donegal. Kristiania: Brøggers

- Sommerfelt A (1927) 'Munster vowels and consonants'. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy 37: 195–244.

- Sommerfelt A (1929) 'South Armagh Irish'. Norsk Tidsskrift for Sprogvidenskap 2: 107–191.

- Sommerfelt A (1965) 'The phonemic structure of the dialect of Torr, Co. Donegal'. Lochlann 3: 237–254.

- Sutton L (1993) Palatal' consonants in spoken Irish'. UC Berkeley Working Papers in Linguistics 1: 164–186.

- Wagner H (1959) 'Gaeilge Theilinn'. Dublin Institute for Advanced Studies. ISBN 1855000555.

- Wells JC (1982) Accents of English 2: The British Isles. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0521285402.

External links

- Daltaí na Gaeilge ('Students of the Irish Language') - includes information on Irish grammar, and hosts sound files of phrases

- Fios Feasa - The Sounds of Irish - description of Irish phones

- Caint Ros Muc - a collection of sound files of Rosmuck speakers

- Irish phonology - software developer's website ('New insights')

- Recordings of the Sounds of Irish - wide range of recordings by a single Donegal speaker that cover most of above

- Foghraidheacht - pronunciation hints for learners (in Irish)

- BBC Northern Ireland- Blas - Irish language, Lesson 1 - How Are You? - includes sound files