Standard Oil Company

Standard Oil was the dominant integrated oil producing, transporting, refining, and marketing company in the United States before 1911. Founded by John D. Rockefeller, it became one of the world's earliest, largest and most profitable corporations, with sales worldwide of its main products, kerosene and lubricating oil. It was established in 1870 and operated as a trust until it was convicted of crime in federal court, given a $29 million fine and was broken into three dozen smaller companies. The verdict was upheld by the Supreme Court of the United States in 1911.

Early years

Standard Oil began as an Ohio partnership formed by John D. Rockefeller, his brother William Rockefeller, Henry Flagler, chemist Samuel Andrews, and a silent partner financier Stephen V. Harkness. Using highly effective and widely criticized tactics, the company absorbed or destroyed most of its competition in Cleveland, Ohio and later throughout the northeastern United States, putting numerous small corporations out of business.

Before the 1890s, John D. Rockefeller dominated the company and indeed was the single most important figure in shaping the new oil industry. We was fastidious in managerial details and delegated heavily, distributing power and policy formation to a system of committees, although always retaining the largest shareholding in the company. Authority was centralized in the company's main office in Cleveland, yet within that office decisions were arrived at in a cooperative manner.[1] In response to state laws attempting to limit the scale of companies, Rockefeller and his partners had to develop innovative defensive strategies. In 1882, they combined their disparate companies, spread across dozens of states, under a single group of trustees. This organization proved so successful that other giant enterprises adopted this "trust" form. At the same time, state and federal laws sought to counter this development with "antitrust" laws.

Management

John D. Rockefeller was the major business strategist until he retired in the late 1890s. His closest advisor until 1883 was hard-driving, imaginative Henry Flagler, (1830-1913), a member of the Harkness family. Flagler excelled as a railroad and pipleine specialist, a drafter and enforcer of contracts, and the sparkplug for fresh ideas.[2]

The Standard Oil Company gained control of the petroleum refining industry in a brief seven year period, 1871-1879. At the time, entry into the industry was easy, the production of crude oil was very competitive, and several competing railroads supplied the transportation. Standard's monopolization of refining by policing the competitive transportation suppliers is an unusual result.[3] Standard realized that the transporters of crude and refined oil had the potential to restrict entry into refining. Standard exploited this potential through the use of contracts that decreased the railroads' incentives to engage in price competition. Standard eliminated the railroads' costly rate wars by guaranteeing an agreed upon share of freight to each railroad. The railroad could no longer increase its market share by lowering its price. In exchange for providing explicit vertical policing services Standard received preferential rates from the railroads, but a rate that exceeded marginal cost. Standard willingly paid this higher rate because it was paying to have its rivals charged an even higher rate, thereby decreasing their ability to compete with Standard. These rate advantages enabled Standard to force its competitors to sell out. Standard shared rents with the railroads, thereby insuring their support against new entrants. Standard's monopolization of refining was based on vertical policing. Only the development of long distance pipelines and the discovery of new producing fields broke down the barriers Standard had constructed in its favor.[4]

Favorable historians note that Standard's market position had been established through an emphasis on efficiency and responsibility. While most companies dumped gasoline (this being before the automobile) in rivers, Standard used it to fuel the company's own machines. Where gigantic mountains of heavy waste grew by other companies' refineries, Rockefeller found ways to market and sell these waste products, creating the first synthetic competitor for beeswax, as well as acquiring the company that invented and produced Vaseline, the Chesebrough Manufacturing Company, which was a Standard company only from 1908 until 1911.

As the company grew larger through more effective business practices, it developed other strategies, including a systematic program of offering to purchase competitors. After purchasing them, Rockefeller shut down the ones he believed to be inefficient while keeping the others. In a seminal deal, in 1868, the Lake Shore Railroad, a part of the New York Central, gave Rockefeller's firm a $0.25 cents/bbl. (71%) discount off of its listed rates in return for a promise to ship at least 60 carloads of oil daily and to handle the loading and unloading on its own, a huge competitive advantage. Smaller companies decried the deals as being unfair because they were not producing enough oil to qualify for discounts.

During 1864-78, Sylvia Crossman Hunt owned and ran a profitable coal oil refinery in Baltimore that was left to her by her estranged husband, William J. Hamill, in 1864. During the 1870's, John D. Rockefeller and the Standard Oil Company sought to dominate crude oil refining in the United States. Johnson Newlon Camden acted as the Standard agent in enacting their plans in Baltimore. In December 1877, he formed the Baltimore United Oil Company and bought out all of the local refiners except Hunt, who leased her plant to the company and continued to oversee the operation herself. She ceded day-to-day control the next year, but continued to be a difficult partner for Standard, who finally bought the plant site from Hunt in 1892. Hunt has been portrayed as a victim who suffered physically and emotionally because of Standard Oil's actions, but she used her health troubles as leverage in negotiations to make the best of a difficult situation.[5]

In 1872, Rockefeller joined the South Improvement Company which would have allowed him to receive rebates for shipping oil but also to receive drawbacks on oil his competitors shipped. When word got out of this arrangement, competitors convinced the Pennsylvania Legislature to revoke South Improvement's charter. No oil was ever shipped under this arrangement.

In one example of Standard's aggressive practices, a rival oil association decided to build an oil pipeline, hoping to overcome the virtual boycott imposed on Standard's competitors. In response, the railroad company (at Rockefeller's direction) denied the consortium permission to run the pipeline across railway land, forcing consortium staff to laboriously decant the oil into barrels, carry them over the railway crossing in carts, and then pump the oil manually back into the pipeline on the other side. When he learned of this tactic, Rockefeller then instructed the railway company to park empty rail cars across the line, thereby preventing the carts from crossing his property.

Standard's actions and secret transport deals helped its kerosene to drop in price from 58 to 26 cents between 1865 and 1870. Competitors might not have appreciated the company's business practices, but consumers appreciated the drop in prices. Standard Oil, being formed well before the discovery of the Spindletop oil field and a demand for oil other than for heat and light, was well placed to control the growth of the oil business. The company was perceived to own and control all aspects of the trade. Oil could not leave the oil field unless Standard Oil agreed to move it: the "posted price" for oil was the price that Standard Oil agents printed on flyers that were nailed to posts in oil producing areas, and producers were in a take-it-or-leave-it position.

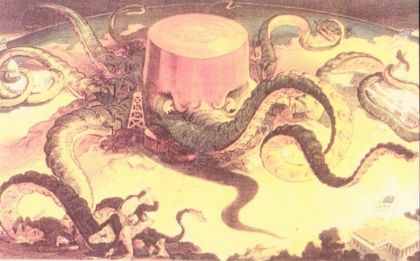

State action

The state of Ohio successfully sued Standard Oil, compelling the dissolution of the trust in 1892. Standard Oil fought this decree, in essence separating off only Standard Oil of Ohio without relinquishing control of that company. Eventually, the state of New Jersey changed its incorporation laws to allow a single company to hold shares in other companies in any other state. Hence, in 1899, the Standard Oil Trust, based at 26 Broadway in New York, was legally reborn as a holding company - a corporation known as the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey (SONJ), which held stock in forty-one other companies, which controlled other companies, which in turn controlled yet other companies, in a conglomerate that was seen by the public as all-pervasive, controlled by a select group of directors, and completely unaccountable.[6]

Singer (2002) narrates how in November 1894, a Texas grand jury indicted Henry Clay Pierce (the president of Waters-Pierce Oil Company), numerous company employees and Standard Oil executives, including John D. Rockefeller himself, of conspiring to monopolize the oil trade in Texas. This was Texas's first litigation to enforce its 1889 antitrust law. The Waters-Pierce company was found guilty and barred from doing business in Texas in 1900. However, it quickly reorganized as a new company, got a new permit to do business in Texas, and continued operations until 1906, when it faced a fresh round of lawsuits. Henry Clay Pierce himself was tried for perjury; he was found not guilty, once again Waters-Pierce was ousted from doing business in Texas. Singer shows that that attacking Waters-Pierce, and Standard Oil, was a popular technique for Texas politicians to win votes but also a way to make money from fines and legal fees.

World trade

In the late 19th centuries, few American companies had success selling to Asia. The major exception was Standard Oil, which arrived two decades before other companies and had a large volume of kerosene sales in China. Standard enjoyed the legal advantages provided by the Sino-Western treaty system that made it immune from local Chinese law. The domineering business style that drew the ire of the American people proved acceptable to the Chinese.[7]

Standard controlled oil distribution in Germany. However, the government sought energy independence and encouraged German banks to finance oil production in Romanian field, hoping to gain independence from American oil and control of all oil distribution in Germany. Stanard won out as the banks failed to wrest distribution control from it, and, despite legislative initiatives, the government failed to create a state oil monopoly.[8]

To meet the problem of transporting oil Standard built pipelines, and pioneered in international sales. From 1870 to 1915 it shipped to Asia "case-oil," that is, tinned petroleum in wooden crates. The development of ocean tankers combined with the dissolution of Standard Oil's monopoly in 1911, ended the case-oil trade by 1915, and demand for kerosene (for indoor lighting) was soon surpassed by a demand for gasoline for automobiles and trucks.

1890-1911

In 1890, Standard Oil of Ohio moved its headquarters out of Cleveland and into its permanent headquarters at 26 Broadway in New York City. Concurrently, the trustees of Standard Oil of Ohio chartered the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey in order to take advantages of New Jersey's more lenient corporate stock ownership laws. Standard Oil of New Jersey eventually became one of many important companies that dominated key markets, such as steel and the railroads.

In 1890, with Standard in mind, Congress passed the Sherman Antitrust Act to make criminal every contract, scheme, deal, or conspiracy to restrain trade. Much legal wrangling focused on the phrase "restraint of trade." The Standard Oil group quickly attracted attention from antitrust authorities leading to a lawsuit filed by then Ohio Attorney General David K. Watson.

Then came Ida M. Tarbell, an American author and journalist, and one of the original "muckrakers". Her father was an oil producer whose business had failed due to Rockefeller's business dealings. Following extensive interviews with a sympathetic senior executive of Standard Oil, Henry H. Rogers, Tarbell's investigations of Standard Oil fueled growing public attacks on Standard Oil and on monopolies in general. Her work was first published in nineteen parts in McClure's magazine, from November 1902 to October 1904, in which year it was published in book form as The History of the Standard Oil Company.

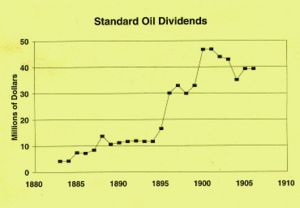

Finances

Standard paid out in dividends during 1882 to 1906 in the amount of $548,436,000, at 65.4% payout ratio. A large part of the profits was not distributed to stockholders, but was put back into the business. The total net earnings from 1882-1906 amounted to $838,783,800, exceeding the dividends by $290,347,800. The latter amount was used for plant expansion.

The Standard Oil Trust itself was controlled by a small group of families. Rockefeller himself stated in 1910: "I think it is true that the Pratt family, the Payne-Whitney family (which were one, as all the stock came from Colonel Payne), the Harkness-Flagler family (which came into the Company together) and the Rockefeller family controlled a majority of the stock during all the history of the Company up to the present time".[9]

These families reinvested most of the dividends in other industries, especially railroads. They also invested heavily in the gas and the electric lighting business (including the giant Consolidated Gas Company of New York City). They made large purchases of stock in U.S. Steel, Amalgamated Copper, and even Corn Products Refining Company.[10]

The opening of giant new fields in Texas and neighboring states after 1901 challenged Standard's control of refining. The Standard pipelines at first were a weapon of near monopoly, but the predominance was challenged by Gulf Oil and the Texas Company, each using the pipeline to gain a firm foothold, operating as competitors of Standard but taking substantially the same attitude toward the use of their pipelines to protect investments.[11]

Anti-trust litigation, and breakup of the company

By 1890, Standard Oil controlled 88% of the refined oil flows in the United States. In 1904 when the lawsuit began it controlled 91% of production and 85% of final sales. Most of its output was kerosene, of which 55% was exported around the world. In terms of cost efficiency, Standard's plants were about the same as competitors. After 1900 it did not try to force competitors out of business by underpricing them. [12] Beyond question, the federal Commissioner of Corporations concluded, the dominant position in the refining industry was due "to unfair practices, to abuse of the control of pipe-lines, to railroad discriminations, and to unfair methods of competition."[13] Gradually, its market share fell to 64% by 1911. Standard did not try to monopolize the exploration and pumping of oil (its share in 1911 was 11%). John D. Rockefeller in 1897 had completely retired from the Standard Oil Company of New Jersey, though he continued to own a large fraction of its shares. Vice-president John D. Archbold then took a large part in the running of the firm.

In 1909, the U.S. Department of Justice filed suit in federal court alleging that Standard had engaged in the following methods to continue the monopoly and restrain interstate commerce: [14]

"Rebates, preferences, and other discriminatory practices in favor of the combination by railroad companies; restraint and monopolization by control of pipe lines, and unfair practices against competing pipe lines; contracts with competitors in restraint of trade; unfair methods of competition, such as local price cutting at the points where necessary to suppress competition; [and] espionage of the business of competitors, the operation of bogus independent companies, and payment of rebates on oil, with the like intent."

The lawsuit further argued that Standard's monopolistic practices took place in the last four years: [15]

"The general result of the investigation has been to disclose the existence of numerous and flagrant discriminations by the railroads in behalf of the Standard Oil Company and its affiliated corporations. With comparatively few exceptions, mainly of other large concerns in California, the Standard has been the sole beneficiary of such discriminations. In almost every section of the country that company has been found to enjoy some unfair advantages over its competitors, and some of these discriminations affect enormous areas."

The government identified four illegal patterns: 1) secret and semi-secret railroad rates; (2) discriminations in the open arrangement of rates; (3) discriminations in classification and rules of shipment; (4) discriminations in the treatment of private tank cars. The government alleged:[16]

"Almost everywhere the rates from the shipping points used exclusively, or almost exclusively, by the Standard are relatively lower than the rates from the shipping points of its competitors. Rates have been made low to let the Standard into markets, or they have been made high to keep its competitors out of markets. Trifling differences in distances are made an excuse for large differences in rates favorable to the Standard Oil Company, while large differences in distances are ignored where they are against the Standard. Sometimes connecting roads prorate on oil--that is, make through rates which are lower than the combination of local rates; sometimes they refuse to prorate; but in either case the result of their policy is to favor the Standard Oil Company. Different methods are used in different places and under different conditions, but the net result is that from Maine to California the general arrangement of open rates on petroleum oil is such as to give the Standard an unreasonable advantage over its competitors

The government said that Standard raised prices to its monopolistic customers, but lowered them to hurt competitors, often disguising its illegal actions by using bogus supposedly "independent" companies it controlled. [17]

"The evidence is, in fact, absolutely conclusive that the Standard Oil Company charges altogether excessive prices where it meets no competition, and particularly where there is little likelihood of competitors entering the field, and that, on the other hand, where competition is active, it frequently cuts prices to a point which leaves even the Standard little or no profit, and which more often leaves no profit to the competitor, whose costs are ordinarily somewhat higher."

Breakup 1911

In 1907 the Company was convicted of violating the Elkins ant-rebate law and fined $29 million. The U.S. Justice Department sued Standard Oil of New Jersey under the federal anti-trust law, the Sherman Antitrust Act of 1890. In 1911, the Supreme Court of the United States upheld the lower court judgment, and forced Standard Oil to separate into thirty-four companies, each with its own distinct board of directors. Standard's president, John D. Rockefeller had, by then, long since retired from any management role, but, as he owned a quarter of all the outstanding shares of the many resultant companies, whose post-dissolution share value mostly doubled, he emerged from the dissolution even more wealthy; the richest man in the world.[18]

The off-shoot companies form the core (or "Seven Sisters") of today's oil industry. They are ExxonMobil (formerly Standard of New Jersey and Standard of New York); ConocoPhillips (the Conoco side, which was Standard's company in the Rocky Mountain states); Chevron (Standard of California); Amoco and Sohio (Standard of Indiana and Standard of Ohio, respectively, now BP of North America), Atlantic Richfield (the Atlantic side, now also a part of BP North America), Marathon Oil (covering western Ohio) and many other smaller companies.

Legacy

Whether the existence of Standard Oil was beneficial is a matter of some controversy.[19] Olien and Olien (2002) demonstrate that Standard's rival oil companies manipulated the media nationally and at the state level to create an overwhelmingly negative public opinion. Using a postmodern approach the Oliens contend that the orthodox view of the oil industry as monopolistic and dominated by ruthless businessmen is a cultural construction. It is a "view that often seems seriously flawed" being based on biased, poorly researched, and in many cases, simply inaccurate texts.[20] The Oliens further suggest that federal and state officials have used those misperceptions as the basis for lawsuits and regulation.

The notion that Standard was a monopoly is rejected by some economists, citing its much reduced market presence by the time of the antitrust trial. In 1890, Rep. William Mason, arguing in favor of the Sherman Antitrust Act, said: "trusts have made products cheaper, have reduced prices; but if the price of oil, for instance, were reduced to one cent a barrel, it would not right the wrong done to people of this country by the trusts which have destroyed legitimate competition and driven honest men from legitimate business enterprise".[21]

The Sherman Act prohibits the restraint of trade. Defenders of Standard Oil insist that the company did not restrain trade, they were simply superior competitors. The federal courts ruled otherwise.

Many analysts agree that the breakup was beneficial to consumers in the long run, and no one has ever proposed that Standard Oil be reassembled in pre-1911 form.[22]

Originally the successor companies scarecely competed, since each had an assigned geographical area. Some were aggressive and expanded, leading to enlarged competition.[23]

Primary sources

- United States Bureau of Corporations, Statement of the Commissioner of Corporations in Answer to the Allegations of the Standard Oil Company (1907) online edition at Google

References

- ↑ Hidy, Ralph W. and Muriel E. Hidy. Pioneering in Big Business, 1882-1911: History of Standard Oil Company (New Jersey) (1955).

- ↑ After 1885 Flager shifted his attention to developing southern Florida through railroads and tourist hotels and founding Palm Beach and Miami. Akin (1988)

- ↑ Granitz, (1990)

- ↑ Granitz, (1990); Arthur M. Johnson, "The Early Texas Oil Industry: Pipelines and the Birth of an Integrated Oil Industry, 1901-1911." Journal of Southern History 1966 32(4): 516-528. Issn: 0022-4642 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ David N. Heller, "Mrs. Hunt and Her Coal Oil Refinery in Baltimore." Maryland Historical Magazine 1992 87(1): 24-41. Issn: 0025-4258

- ↑ Yergin, pp.96-98

- ↑ James Thomas Gillam, Jr., "The Standard Oil Company in China (1863-1930)." PhD dissertation Ohio State U. 1987. 393 pp. DAI 1987 48(4): 995-A. DA8710001

- ↑ Inge Baumgart, and Benneckenstein, Horst. "Der Kampf Des Deutschen Finanzkapitals in Den Jahren 1897 Bis 1914 Für Ein Reichspetroleummonopol," Jahrbuch Für Wirtschaftsgeschichte 1980 (2): 95-120. Issn: 0075-2800

- ↑ Chernow, 1998, p.291

- ↑ Jones, Eliot. The Trust Problem in the United States pp. 89-90 (1922) (hereinafter Jones).

- ↑ Arthur M. Johnson, "The Early Texas Oil Industry: Pipelines and the Birth of an Integrated Oil Industry, 1901-1911." Journal of Southern History 1966 32(4): 516-528. Issn: 0022-4642 Fulltext: in Jstor

- ↑ Jones pp 58-59, 64.

- ↑ Jones. pp. 65-66.

- ↑ Manns, Leslie D., "Dominance in the Oil Industry: Standard Oil from 1865 to 1911" in David I. Rosenbaum ed., Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose it and the Impact on Economic Performance, p. 11 (Praeger 1998).

- ↑ Jones, p. 73.

- ↑ Jones, p 75-76.

- ↑ Jones, p. 80.

- ↑ Yergin, p.113

- ↑ see [1] [2]

- ↑ Olien and Olien (2002) p. x

- ↑ Congressional Record, 51st Congress, 1st session, House, June 20, 1890, p. 4100.

- ↑ David I. Rosenbaum, Market Dominance: How Firms Gain, Hold, or Lose it and the Impact on Economic Performance, 1998, pp.31-33

- ↑ D. F. Dixon, "The Growth of Competition among the Standard Oil Companies in the United States, 1911-1961." Business History 1967 9(1): 1-29. Issn: 0007-6791 Fulltext: in Ebsco