American conservatism

American conservatism comprises a family of political ideologies in opposition to liberalism, socialism, secularism and communism. Main themes include fiscal conservatism (opposition to high government spending; fear of high government debt), opposition to high taxes, belief on free markets (or economic liberalism or laissez-faire, and opposition to government regulation); opposition to many government welfare programs (often coupled with a demand for more private welfare). Most conservatives have been hostile to labor unions; in recent years the school teachers' unions have come under fire as fostering poor education through government monopoly, inefficiency, and liberalism. In social issues the split is between libertarians who tolerate many forms of private behavior, and social conservatives with a high respect for religious and cultural traditions and prohibitions. Social conservatives especially have opposed changes in traditional moral codes especially regarding sexual and gender behavior (such as opposition to divorce, contraception, abortion, homosexuality and gay marriage, and women in the combat roles in the military). Most conservatives are hostile to illegal drugs, and before 1933 many supported the prohibition of alcohol. "Affirmative action" for blacks, women and minorities are often called "quotas" and are rejected. In recent years opposition to illegal immigrants has fired up many conservatives, although the business community (which hired the illegals by the millions), along with President George W. Bush, supports a path to citizenship that the oppents denouce as "amnesty." (Reagan sponsored the first amnesty program for ilelgals in 1987.)

Many conservatives favor a strong military and police; many oppose "internationalism" (in the sense of allowing organizations like the United Nations or public opinion in the other countries to shape American policies). Nearly all conservatives have actives opposed Communism and Socialism at home; most opposed international Communism, especially in Cuba, the Soviet Union (before 1989) and China (before 1972). Many conservatives display nativism, or strong hostility toward people who do they say do not belong in America (such as illegal immigrants in the 21st century, or Asian immigrants in the 19th and 20th centuries, or Catholics in the 18th and 19th centuries). Many conservatives supported states' rights (in opposition to the federal government), but that position has been under debate recently. The "elite" style of conservatism, typified by William Howard Taft and his son Robert A. Taft, emphasized the court system as a conservative bulwark against popular threats to the rights of Americans. The "populist" version (which includes Thomas Jefferson, Theodore Roosevelt and many recent spokesmen), sees the courts as too elitist and wants more popular control over Supreme Court decisions, often arguing against "activist" judges.

There is no one model, and no one person or organization that includes every aspect; indeed some themes are mutually at odds or contradictory. The most influential political leaders in recent decades included Robert A. Taft in the 1940s, Barry Goldwater in the 1960s, and Ronald Reagan in the 1980s. Important writers and spokesmen included Russell Kirk. Milton Friedman, William F. Buckley and George F. Will.

Politically, self-identified "conservatives" have voted 75-80% Republican in recent years. While conservatives were once significant minorities in both major parties, the conservative wing of the Democratic party has faded and most conservatives today identify themselves as Republicans or independents. In 2000 and 2004, about 80% of self-described conservatives voted Republican.[1][2]

In the United States modern conservatism coalesced in the latter half of the 20th century, responding over time to the political and social change associated with events such as the Great Depression, tension with the Soviet Union in the Cold War, the Civil Rights Movement, the counterculture of the 1960s, the deregulation of the economy in the late 1970s and early 1980s, the overthrow of the New Deal Coalition in the 1980s, and the terrorist threat of the 21st century. Its prominence has been aided, in part, by the emergence of vocal and influential economists, politicians, writers, and media personalities.

History

Founding Fathers

The Loyalists of the American Revolution were mostly political conservatives, some of whom produced political discourse of a high order, including lawyer Joseph Galloway and governor-historian Thomas Hutchinson. After the war, the great majority remained in the U.S. and became citizens, but some leaders emigrated to other places in the British Empire. Samuel Seabury was a Loyalist who returned and as the first American bishop played a major role in shaping the Episcopal religion, a stronghold of conservative social values.

The Founding Fathers created the single most important set of political ideas in American history, known as republicanism, which all groups, liberal and conservative alike, have drawn from. During the First Party System (1790s-1820s) the Federalist Party, led by Alexander Hamilton, developed an important variation of republicanism that can be considered conservative. Rejecting monarchy and aristocracy, they emphasized civic virtue as the core American value. The Federalists spoke for the propertied interests and the upper classes of the cities. They envisioned a modernizing land of banks and factories, with a strong army and navy. George Washington was their great hero.

On many issues American conservatism also derives from the republicanism of Thomas Jefferson and his followers, especially John Randolph of Roanoke and his "Old Republicans" or "Quids." They idealized the yeoman farmer as the epitome of civic virtue, warned that banking and industry led to corruption, that is to the illegitimate use of government power for private ends. Jefferson himself was a vehement opponent of what today is called "judicial activism". [3] The Jeffersonians stressed States' Rights and small government. During the Second Party System (1830-54) the Whig Party attracted most conservatives, such as Daniel Webster of New England.

Ante-Bellum: Calhoun and Webster

Daniel Webster and other leaders of the Whig Party, called it the conservative party in the late 1830s.[4] John C. Calhoun, a Democrat, articulated a sophisticated conservatism in his writings. Richard Hofstadter (1948) called him "The Marx of the Master Class." Calhoun argued that a conservative minority should be able to limit the power of a "majority dictatorship" because tradition represents the wisdom of past generations. (This argument echoes one made by Edmund Burke, the founder of British conservatism, in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790)). Calhoun is considered the father of the idea of minority rights, a position adopted by liberals in the 1960s in dealing with Civil Rights.

The conservatism of the antebellum period is contested territory; conservatives of the 21st century disagree over what comprises their heritage. Thus William J. Bennett (2006) a prominent conservative leader, tells conservatives to NOT honor Calhoun, Know-Nothings, Copperheads and 20th century isolationists.

Lincoln to Cleveland

Since 1865 the Republican party has identified itself with President Abraham Lincoln, who was the ideological heir of the Whigs and of both Jefferson and Hamilton. As the Gettysburg Address shows, Lincoln cast himself as a second Jefferson bringing a second birth of freedom to the nation that had been born 86 years before in Jefferson's Declaration. The Copperheads of the Civil War reflected a reactionary opposition to modernity of the sort repudiated by modern conservatives. A few libertarians have adopted a neo-Copperhead position, arguing Lincoln was a dictator who created an all-powerful government.

In the late 19th century the Bourbon Democrats, led by President Grover Cleveland, preached against corruption, high taxes (protective tariffs), and imperialism, and supported the gold standard and business interests. They were overthrown by William Jennings Bryan in 1896, who moved the mainstream of the Democratic Party permanently to the left.

The 1896 presidential election was the first with a conservative versus liberal theme in the way in which these terms are now understood. Republican William McKinley won using the pro-business slogan "sound money and protection," while Bryan's anti-bank populism had a lasting effect on economic policies of the Democratic Party.

William Graham Sumner, Yale professor (1872-1910) and polymath, vigorously promoted a libertarian conservative ethic. After dallying with Social Darwinism under the influence of Herbert Spencer, he rejected evolution in his later works, and strongly opposed imperialism. He opposed monopoly and paternalism in theory as a threat to equality, democracy and middle class values, but was vague on what to do about it.[5]

Early 20th century

- See also: Old Right (United States)

In the Progressive Era (1890s-1932), regulation of industry expanded as conservatives led by Senator Nelson Aldrich of Rhode Island were put on the defensive. However, Aldrich's proposal for a strong national banking system was enacted as the Federal Reserve System in 1913. Theodore Roosevelt, the dominant personality of the era, was both liberal and conservative by turns. As a conservative he led the fight to make the country a major naval power, and demanded entry into World War I to stop what he saw as the German attacks on civilization. William Howard Taft promoted a strong federal judiciary that would overrule excessive legislation. Taft defeated Roosevelt on that issue in 1912, forcing Roosevelt out of the GOP and turning it to the right for decades. As president, Taft remade the Supreme Court with five appointments; he himself presided as chief justice in 1921-30, the only former president ever to do so.

Pro-business Republicans returned to dominance in 1920 with the election of President Warren G. Harding. The presidency of Calvin Coolidge (1923-29) was a high water mark for conservatism, both politically and intellectually. Classic writing of the period includes Democracy and Leadership (1924) by Irving Babbitt and H.L. Mencken's magazine American Mercury (1924-33). The Efficiency Movement attracted many conservatives such as Herbert Hoover with its pro-business, pro-engineer approach to solving social and economic problems. In the 1920s many American conservatives generally maintained anti-foreign attitudes and, as usual, were disinclined toward changes to the healthy economic climate of the age.

During the Great Depression, other conservatives participated in the taxpayers' revolt at the local level. From 1930 to 1933, Americans formed as many as 3,000 taxpayers' leagues to protest high property taxes. These groups endorsed measures to limit and rollback taxes, lowered penalties on tax delinquents, and cuts in government spending. A few also called for illegal resistance (or tax strikes). Probably the best known of these was led by the Association of Real Estate Taxpayers in Chicago which, at its height, had 30,000 dues-paying members.

An important intellectual movement, calling itself Southern Agrarians and based in Nashville, brought together like-minded novelists, poets and historians who argued that modern values undermined the traditions of American republicanism and civic virtue.

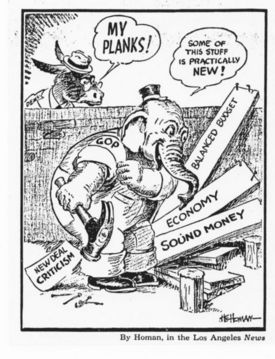

The Depression brought liberals to power under President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933). Indeed the term "liberal" now came to mean a supporter of the New Deal. In 1934 Al Smith and pro-business Democrats formed the American Liberty League to fight the new liberalism, but failed to stop Roosevelt's shifting the Democratic party to the left. In 1936 the Republicans rejected Hoover and tried the more liberal Alf Landon, who carried only Maine and Vermont. When Roosevelt tried to pack the Supreme Court in 1937 the conservatives finally cooperated across party lines and defeated it with help from Vice President John Nance Garner. Roosevelt unsuccessfully tried to purge the conservative Democrats in the 1938 election. The conservatives in Congress then formed a bipartisan informal Conservative Coalition of Republicans and southern Democrats. It largely controlled Congress from 1937 to 1964. Its most prominent leaders were Senator Robert Taft, a Republican of Ohio, and Senator Richard Russell, Democrat of Georgia.

In the United States, the Old Right, also called the Old Guard, was a group of libertarian, free-market anti-interventionists, originally associated with Midwestern Republicans and Southern Democrats. The Republicans (but not the southern Democrats) were isolationists in 1939-41, (see America First), and later opposed NATO and U.S. military intervention in the Korean War.

Later 20th century: Goldwater, Buckley, the Dixiecrats

By 1950, American liberalism was so dominant intellectually that author Lionel Trilling could dismiss contemporary conservatism as "irritable mental gestures which seek to resemble ideas." [6]

In the 1950s, principles for a conservative political movement were hashed out in books like Russell Kirk's The Conservative Mind (1953) and in the pages of the magazine National Review, founded by William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955.

Whereas Taft's Old Right had been isolationist the new conservatism favored American intervention overseas to oppose communism. It looked to the Founding Fathers for historical inspiration as opposed to Calhoun and the antebellum South.

Ironically, as the Democratic Party became identified with the American Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s through 1970s, many former southern Democrats joined the Republican Party, even in the face of greater proportional support for civil rights legislation among Republicans, thereby increasingly cementing the Republicans' alignment as a conservative party. Senator Barry Goldwater, sometimes known as "Mr. Conservative," argued in his 1960 Conscience of a Conservative that conservatives split on the issue of civil rights due to some conservatives advocating ends (integration, even in the face of what they saw as unconstitutional Federal involvement) and some advocating means (constitutionality above all else, even in the face of segregation). Republicans joined northern Democrats to override a filibuster of the Civil Rights Act in 1964. Later that year, Goldwater was resoundingly defeated by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

Out of this defeat emerged the New Right, a political movement that coalesced through grassroots organizing in the years preceding Goldwater's 1964 presidential campaign. The American New Right is distinct from and opposed to the more moderate/liberal tradition of the so-called Rockefeller Republicans, and succeeded in building a policy approach and electoral apparatus that propelled Ronald Reagan into the White House in the 1980 presidential election.

Nixon, Reagan, and Bush

See also: Nixon and the liberal consensus

The Republican administrations of President Richard Nixon in the 1970s were characterized more by their emphasis on realpolitik, détente, and economic policies such as wage and price controls, than by their adherence to conservative views in foreign and economic policy.

Thus, it was not until the election of 1980 and the subsequent eight years of Ronald Reagan's presidency that the American conservative movement truly achieved ascendancy. In that election, Republicans took control of the Senate for the first time since 1954, and conservative principles dominated Reagan's economic and foreign policies, with supply side economics and strict opposition to Soviet Communism defining the Administration's philosophy.

An icon of the American conservative movement, Reagan is credited by his supporters with transforming the politics of 1980s United States, galvanizing the success of the Republican Party, uniting a coalition of economic conservatives who supported his economic policies, known as "Reaganomics," foreign policy conservatives who favored his staunch opposition to Communism and the Soviet Union over the détente of his predecessors, and social conservatives who identified with Reagan's conservative religious and social ideals.

It is hotly debated whether the successive Republican Administrations of Presidents George H. W. Bush and George W. Bush are truly conservative. George W. Bush campaigned in 2000 as a "compassionate conservative," but in his second term, conservative critics have negatively cited his increases in Federal spending and the Federal deficits; in contrast, he is often lauded by some conservatives for his commitment to conservative social and religious values, tax-cut initiatives, and a strong national defense.

Types of conservatism

Defining "American conservatism" requires a definition of conservatism in general, and the term is applied to a number of ideas and ideologies, some more closely related to core conservative beliefs than others.

1. Classical or institutional conservatism - Opposition to rapid change in governmental and societal institutions. This kind of conservatism is anti-ideological insofar as it emphasizes process (slow change) over product (any particular form of government). To the classical conservative, whether one arrives at a right- or left-leaning government is less important than whether change is effected through rule of law rather than through revolution and sudden innovation.

2. Ideological conservatism or right-wing conservatism -- In contrast to the anti-ideological classical conservatism, right-wing conservatism is, as its name implies, ideological. It is typified by three distinct subideologies: social conservatism, fiscal conservatism, and economic liberalism. Together, these subideologies comprise the conservative ideology of people in some English-speaking countries: separately, these subideologies are incorporated into other political positions.

3. Neoconservatism, in its United States usage, has come to refer to the views of a subclass of conservatives who support a more assertive foreign policy coupled with one or more other facets of social conservatism, in contrast to the typically isolationist views of early- and mid-20th Century conservatives. Neoconservatism was first described by a group of disaffected liberals, and thus Irving Kristol, usually credited as its intellectual progenitor, defined a "neoconservative" as "a liberal who was mugged by reality." Although originally regarded as an approach to domestic policy (the founding instrument of the movement, Kristol's The Public Interest periodical, did not even cover foreign affairs), through the influence of figures like Dick Cheney, Robert Kagan, Richard Perle, Ken Adelman and (Irving's son) William Kristol, it has become more famous for its association with the foreign policy of the George W. Bush Administration.

4. Small government conservatism -- Small government conservatives look for a decreased role of the federal government, and as well weaker state governments. Small government conservatives rather than focusing of the protections given individuals by the Bill of Rights, they try to weaken the federal government, thereby following the Founding Fathers who were suspicious of a centralized, unitary state like Britain, from which they had just won their freedom.

5. Paleoconservatism, which arose in the 1980s in reaction to neoconservatism, stresses tradition, civil society, classical federalism and heritage of Christendom. They see social democracy, ideology, and managerial society as malevolent attempts to remake humanity.[13] Supporters say that the dominant forces in Western society no longer support conserving the traditions, institutions, and values that created and formed it.[14] Therefore, they say true conservatives must oppose the status quo. In statecraft, they call for decentralism, local rule, private property and minimal bureaucracy.[15] In society, they are traditionalist, support a Christian moral order and proclaim the nuclear family is a wise system. Some like Samuel P. Huntington argue that multiracial, multiethnic, and egalitarian states are inherently unstable.[7] Paleos are generally noninterventionist, arguing that American entry into foreign wars is unnecessary and unwise.

Conservatism as "ideology," or political philosophy

Classical conservatives tend to be anti-ideological, and some would even say anti-philosophical,[8] promoting rather, as Russell Kirk explains, a steady flow of "prescription and prejudice." Kirk's use of the word "prejudice" here is not intended to carry its contemporary pejorative connotation: a conservative himself, he believes that the inherited wisdom of the ages may be a better guide than apparently rational individual judgment.

In contrast to classical conservatism, social conservatism and fiscal conservatism are concerned with consequences as well as means.

There are two overlapping subgroups of social conservatives—the traditional and the religious. Traditional conservatives strongly support traditional codes of conduct, especially those they feel are threatened by new ideas. For example, traditional conservatives may oppose the use of female soldiers in combat. Religious conservatives focus on rules laid down by religious leaders. In the United States, they especially oppose abortion and homosexuality and often favor the use of government institutions, such as schools and courts, to promote Christianity.

Fiscal conservatives support limited government, limited taxation, and a balanced budget. Some admit the necessity of taxes, but hold that taxes should be low. A recent movement against the inheritance tax labels such a tax a death tax. Fiscal conservatives often argue that competition in the free market is more effective than the regulation of industry, with the exception of industries that exhibit market dominance or monopoly powers. For some this is a matter of principle, as it is for the libertarians and others influenced by thinkers such as Ludwig von Mises, who believed that government intervention in the economy is inevitably wasteful and inherently corrupt and immoral. For others, "free market economics" simply represents the most efficient way to promote economic growth: they support it not based on some moral principle, but pragmatically, because it "works".

Most modern American fiscal conservatives accept some social spending programs not specifically delineated in the Constitution. As such, fiscal conservatism today exists somewhere between classical conservatism and contemporary consequentialist political philosophies.

Throughout much of the 20th century, one of the primary forces uniting the occasionally disparate strands of conservatism, and uniting conservatives with their liberal and socialist opponents, was opposition to Communism, which was seen not only as an enemy of the traditional order, but also the enemy of western freedom and democracy.

Social conservatism and tradition

Social conservatism or "cultural conservatism" is generally dominated by defense of traditional social norms and values, of local customs and of societal evolution, rather than social upheaval, though the distinction is not absolute. Often based upon religion, modern cultural conservatives, in contrast to "small-government" conservatives and "states-rights" advocates, increasingly turn to the federal government to overrule the states in order to preserve educational and moral standards.

Social conservatives emphasize traditional views of social units such as the family, church, or locale. Social conservatives would typically define family in terms of local histories and tastes. To the Protestant or Catholic, social conservatism may entail support for defining marriage as between a man and a woman (thereby banning gay marriage) and laws to criminalize abortion.

From this same respect for local traditions comes the correlation between conservatism and patriotism. Conservatives, out of their respect for traditional, established institutions, tend to strongly identify with nationalist movements, existing governments, and its defenders: police, the military, and national poets, authors, and artists. Conservatives hold that military institutions embody admirable values like honor, duty, courage, and loyalty. Military institutions are independent sources of tradition and ritual pageantry that conservatives tend to admire. In its degenerative form, such respect may become typified by jingoism, populism, and nativism.

Some conservatives want to use federal power to block state actions they disapprove of. Thus in the 21st century came support for the "No Child Left Behind" program, support for a constitutional amendment prohibiting same-sex marriage, support for federal laws overruling states that attempt to legalize marijuana or assisted suicide. The willingness to use federal power to intervene in state affairs is the negation of the old state's rights position.

Anti-intellectualism has sometimes been a component of social conservatism, especially when intellectuals were seen in opposition to religion or as proponents of "progress". [9] In the 1920s, liberal leader William Jennings Bryan led the battle against Darwinism and evolution, a battle which still goes on in conservative circles today.

Fiscal conservatism

Fiscal conservatism is the economic and political policy that advocates restraint of governmental taxation and expenditures. Fiscal conservatives since the 18th century have argued that debt is a device to corrupt politics; they argue that big spending ruins the morals of the people, and that a national debt creates a dangerous class of speculators. The argument in favor of balanced budgets is often coupled with a belief that government welfare programs should be narrowly tailored and that tax rates should be low, which implies relatively small government institutions.

This belief in small government combines with fiscal conservatism to produce a broader economic liberalism, which wishes to minimize government intervention in the economy. This amounts to support for laissez-faire economics. This economic liberalism borrows from two schools of thought: the classical liberals' pragmatism and the libertarian's notion of "rights." The classical liberal maintains that free markets work best, while the libertarian contends that free markets are the only ethical markets.

Fiscal conservatives have complained about high-spending conservatives, such as Ronald Reagan, George H. W. Bush, and George W. Bush, especially regarding their high military spending.

Economic liberalism

The economic philosophy of conservatives in the United States tends to be liberalism. Economic liberalism can go well beyond fiscal conservatism's concern for fiscal prudence, to a belief or principle that it is not prudent for governments to intervene in markets. It is also, sometimes, extended to a broader "small government" philosophy. Economic liberalism is associated with free-market, or laissez-faire economics.

Economic liberalism, insofar as it is ideological, owes its creation to the "classical liberal" tradition, in the vein of Adam Smith , Friedrich A. Hayek [10], Milton Friedman [11], and Ludwig von Mises [12].

Classical liberals and libertarians support free markets on moral, ideological grounds: principles of individual liberty morally dictate support for free markets. Supporters of the moral grounds for free markets include Ayn Rand and Ludwig von Mises. The liberal tradition is suspicious of government authority, and prefers individual choice, and hence tends to see capitalist economics as the preferable means of achieving economic ends.

Modern conservatives, on the other hand, derive support for free markets from practical grounds. Free markets, they argue, are the most productive markets. Thus the modern conservative supports free markets not out of necessity, but out of expedience. The support is not moral or ideological, but driven on the Burkean notion of prescription: what works best is what is right.

Another reason why conservatives support a smaller role for the government in the economy is the belief in the importance of the civil society. As noted by Alexis de Tocqueville, a bigger role of the government in the economy will make people feel less responsible for the society. The responsibilities must then be taken over by the government, requiring higher taxes. In his book Democracy in America, De Tocqueville describes this as "soft oppression".

It must be noted that while classical liberals and modern conservatives reached free markets through different means historically, to-date the lines have blurred. Rarely will a politician claim that free markets are "simply more productive" or "simply the right thing to do" but a combination of both. This blurring is very much a product of the merging of the classical liberal and modern conservative positions under the "umbrella" of the conservative movement.

The archetypal free-market conservative administrations of the late 20th century -- the Margaret Thatcher government in the UK and the Ronald Reagan government in the U.S. -- both held the unfettered operation of the market to be the cornerstone of contemporary modern conservatism (this philosophy is sometimes called neoliberalism). To that end, Thatcher privatized industries and Reagan cut the maximum capital gains tax from 28% to 20%, though in his second term he raised it back up to 28%. Contrary to the neoliberal ideal, Reagan increased government spending from about 700 billion in his first year in office to about 900 billion in his last year.

The interests of capitalism, fiscal and economic liberalism, and free-market economy do not necessarily coincide with those of social conservatism. At times, aspects of capitalism and free markets have been profoundly subversive of the existing social order, as in economic modernization, or of traditional attitudes toward the proper position of sex in society, as in the now near-universal availability of pornography. To that end, on issues at the intersection of economic and social policy, conservatives of one school or another are often at odds.

Conservatism in the United States electoral politics

In the United States, the Republican Party is generally considered to be the party of conservatism. This has been the case since the 1960s, when the conservative wing of that party consolidated its hold, causing it to shift permanently to the right of the Democratic Party. The most dramatic realignment was the white South, which moved from 3-1 Democratic to 3-1 Republican between 1960 and 2000.

In addition, many United States libertarians, in the Libertarian Party and even some in the Republican Party, see themselves as conservative, even though they advocate significant economic and social changes – for instance, further dismantling the welfare system or liberalizing drug policy. They see these as conservative policies because they conform to the spirit of individual liberty that they consider to be a traditional American value. It should be noted that although libertarians have had closer ties with conservatives, they do not typically believe themselves to be conservative.

On the other end of the scale, some Americans see themselves as conservative while not being supporters of free market policies. These people generally favor protectionist trade policies and government intervention in the market to preserve American jobs. Many of these conservatives were originally supporters of neoliberalism who changed their stance after perceiving that countries such as China were benefiting from that system at the expense of American production. However, despite of their support for protectionism, they still tend to favor other elements of free market philosophy, such as low taxes, limited government and balanced budgets.

Conservative geography, "Red States"

Today in the U.S., geographically the South, the Midwest, the non-coastal West, and Alaska are conservative strongholds. The division of the United States into conservative "red states" and liberal "blue states" works well for elections but is too crude to deal with individuals. artificial and does not reflect the actual distribution of voters of either stripe. College towns are generally liberal and Democratic. People who live in rural areas and the "exurbs" tend to be conservative (socially, culturally, and/or fiscally) and vote Republican. People who live in the urban cores of large metropolitan areas tend to be liberal and vote Democrat. The medium cities and suburbs are split. Thus, within each state, there is a division between city and country, between town and gown. [16][17]

Other topics

Conservatism and change

"Conservatism" is not necessarily opposed to change. For example, the Reagan administration in the U.S. and that of Margaret Thatcher in the UK both professed conservatism, but during Reagan's term of office, the United States radically revised its tax code, while Thatcher dismantled several previously nationalized industries and made major reforms in taxation and housing; furthermore, both took, or attempted, significant measures to reduce the power of labor unions. These changes were justified on the grounds that they were changing back to the conditions of a better time.

Various "Conservative" parties have presided over periods of economic expansion which have been disruptive of previous social and political arrangements, for example the Republican Party in 1920s America, and the Bharatiya Janata Party in late 1990s India.

Political memory can be of various durations, and the traditions conservatives embrace can be of relatively recent invention. The prevalence of the nuclear family is, at most, a few centuries old. Western democracy itself is a late 18th century invention. Corporate capitalism is even newer. The reference to God in the Pledge of Allegiance only goes back to the 1950s. The race-blind meritocracy now embraced by many U.S. conservatives as an alternative to affirmative action would have seemed quite radical to most U.S. conservatives in the 1950s.

Contemporary conservative platform

In the United States and western Europe, conservatism is generally associated with the following views, as noted by Russell Kirk in his book, The Conservative Mind:

- "Belief in a transcendent order, or body of natural law, which rules society as well as conscience."

- "Affection for the proliferating variety and mystery of human existence, as opposed to the narrowing uniformity, egalitarianism, and utilitarian aims of most radical systems;"

- "Persuasion that freedom and property are closely linked: separate property from private possession, and the Leviathan becomes master of all."

- "Faith in prescription and distrust of 'sophisters, calculators, and economists' who would reconstruct society upon abstract designs."

- "Recognition that change may not be salutary reform: hasty innovation may be a devouring conflagration, rather than a torch of progress."

There is currently debate over whether the policies of the George W. Bush Administration accurately reflect American conservative values: Peggy Noonan, writing for the Wall Street Journal, recently said, "For this we fought the Reagan revolution? A year into his second term, President Bush is redefining what it means to be a Republican and a conservative.

Conservatism and the Courts

One stream of conservatism exemplified by William Howard Taft extols independent judges as experts in fairness and the final arbiters of the Constitution. However, another more populist stream of conservatism condemns "judicial activism" -- that is, judges rejecting laws passed by Congress or interpreting old laws in new ways. This position goes back to Jefferson's vehement attacks on federal judges and to Abraham Lincoln's attacks on the Dred Scott decision of 1857. In 1910 Theodore Roosevelt broke with most of his lawyer friends and called for popular votes that could overturn unwelcome decisions by state courts. President Franklin D. Roosevelt did not attack the Supreme Court directly in 1937, but ignited a firestorm of protest by a proposal to add seven new justices. The Warren Court of the 1960s came under conservative attack for decisions regarding redistricting, desegregation, and the rights of those accused of crimes.

A more recent variant that emerged in the 1970s is "originalism", the assertion that the United States Constitution should be interpreted to the maximum extent possible in the light of what it meant when it was adopted. Originalism should not be confused with a similar conservative ideology, strict constructionism, which deals with the interpretation of the Constitution as written, but not necessarily within the context of the time when it was adopted.

Semantics, language, and media

Language

In the late 20th century conservatives found new ways to use language and the media to support their goals and to shape the vocabulary of political discourse. Thus the use of "Democrat" as an adjective, as in "Democrat Party" was used first in the 1930s by Republicans to criticize large urban Democratic machines. Republican leader Harold Stassen stated in 1940, "I emphasized that the party controlled in large measure at that time by Hague in New Jersey, Pendergast in Missouri and Kelly Nash in Chicago should not be called a 'Democratic Party.' It should be called the 'Democrat party.'"[13] In 1947 Senator Robert A. Taft said, "Nor can we expect any other policy from any Democrat Party or any Democrat President under present day conditions. They cannot possibly win an election solely through the support of the solid South, and yet their political strategists believe the Southern Democrat Party will not break away no matter how radical the allies imposed upon it."[14]. The use of "Democrat" as an adjective is standard practice in Republican national platforms (since 1948), and has been standard practice in the White House since 2001, for press releases and speeches. It seems to be quite common on conservative talk radio.

Radio

Conservatives gained a major new communications medium with the advent of talk radio in the 1990s. Rush Limbaugh proved there was a huge nationwide audience for specific and heated discussions of current events from a conservative viewpoint. Major hosts who describe themselves as either conservative or libertarian include: Michael Peroutka, Jim Quinn, Ben Ferguson, Lars Larson, Sean Hannity, G. Gordon Liddy, Laura Ingraham, Mark Levin, Michael Savage, Glenn Beck, Larry Elder, Neal Boortz, Michael Reagan, and Ken Hamblin. The Salem Radio Network syndicates a group of religiously-oriented Republican activists, including Catholic Hugh Hewitt, and Jewish conservatives Dennis Prager and Michael Medved. One popular Jewish conservative Dr. Laura offers parental and personal advice, but is an outspoken critic of social and political issues. Libertarians such as Neal Boortz (based in Atlanta), and Mark Davis (based in Ft. Worth and Dallas, Texas) reach large local audiences. Art Bell held some Libertarian views before his talk show adapted a new paranormal format. Many of these hosts also publish books, write newspaper columns, appear on television, and give public lectures (Limbaugh was a pioneer of this model of multi-media punditry). At a rarer level, University of Chicago psychology professor Milt Rosenberg has been hosting a talk show "Extension 720"[15] on WGN radio in Chicago since the 1970s. Talk radio provided an immediacy and a high degree of emotionalism that seldom is reached on television or in magazines. Pew researchers found in 2004 that 17% of the public regularly listens to talk radio. This audience is mostly male, middle-aged, well-educated and conservative. Among those who regularly listen to talk radio, 41% are Republican and 28% are Democrats. Furthermore, 45% describe themselves as conservatives, compared with 18% who say they are liberal.[16]

Television

Pew further reports that conservatives and liberals are increasingly polarized in their TV news preferences. The cable news audience is more Republican and more strongly conservative than the public at large or the network news audience. Among regular cable news viewers, 43% describe their political views as conservative, compared with 33% of regular network news viewers; 37% of cable viewers are moderate, compared to 41% of network viewers; and 14% are self-described liberals versus 18% of network viewers.

The audience for the Fox News Channel has grown since 1998, attracting more conservative and Republican viewers. In 1998, the Fox News audience mirrored the public in terms of both partisanship and ideology. However, the percentage of Fox News Channel viewers who identify as Republicans has increased steadily from 24% in 1998, to 29% in 2000, 34% in 2002, and 41% in 2004. Over the same time period, the percentage of Fox viewers who describe themselves as conservative has increased from 40% to 52%.[17]

Conservative political movements

Contemporary political conservatism — the actual politics of people and parties professing to be conservative — in most western democratic countries is an amalgam of social and institutional conservatism, generally combined with fiscal conservatism, and usually containing elements of broader economic conservatism as well. As with liberalism, it is a pragmatic and protean politics, opportunistic at times, rooted more in a tradition than in any formal set of principles.

It is certainly possible for one to be a fiscal and economic conservative but not a social conservative; in the United States at present, this is the stance of libertarianism. It is also possible to be a social conservative but not an economic conservative — at present, this is a common political stance in, for example, Ireland — or to be a fiscal conservative without being either a social conservative or a broader economic conservative, such as the "deficit hawks" of the Democratic Party (United States). In general use, the unqualified term "conservative" is often applied to social conservatives who are not fiscal or economic conservatives. It is rarely applied in the opposite case, except in specific contrast to those who are neither.

Criticism

Some criticisms of American conservatism on ideological or philosophical grounds are:

- A common progressive criticism of conservatism is that its emphasis on tradition serves to belay the "inherently necessary" evolution of a nation or society - particularly as one exists within the shifting paradigms of a constantly changing world.[18]

- Progressive critics also attack the predominate economic positions among conservatives for freer trade, weaker unions and limited government intervention (with regards to welfare programs and a minimum wage) saying they have contributed to the rise in income inequality in America. [19]

- Many American conservatives believe that the United States is or should be a Christian nation.[20] Critics say that forcing students (or anyone) to acknowledge a particular religion violates the Constitution. Likewise critics say conservatives who believe that government or public schools should judge scientific questions (especially regarding evolution) by the Bible are violating the constitution. [21]

- Barbara R. Bergmann claims that conservative opposition to affirmative action might lead to a return to de facto segregation.[22]

Bibliography

- Frohnen,Bruce et al eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006), the most detailed reference

Intellectual history

- Crunden, Robert M. The Mind and Art of Albert Jay Nock (1964)

- Dunn, Charles W. and J. David Woodard; The Conservative Tradition in America Rowman & Littlefield, 1996 online edition

- Ebenstein, Lanny. Milton Friedman: A Life (2007), full-scale biography, 186pp. excerpt and text search

- Filler, Louis. Dictionary of American Conservatism Philosophical Library, (1987)

- Foner, Eric. "Radical Individualism in America: Revolution to Civil War," Literature of Liberty, vol. 1 no. 3, 1978 pp 1-31 online

- Frohnen, Bruce et al eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006), the most detailed reference

- Doherty, Brian. Radicals for Capitalism: A Freewheeling History of the Modern American Libertarian Movement (2007)

- Federici, Michael P. Eric Voegelin: The Restoration of Order (2002)

- Genovese, Eugene. The Southern Tradition: The Achievement and Limitations of an American Conservatism (1994) excerpt and text search

- Gottfried, Paul. The Conservative Movement Twayne, 1993.

- Guttman, Allan. The Conservative Tradition in America Oxford University Press, 1967.

- Judis, John B. William F. Buckley, Jr.: Patron Saint of the Conservatives (1988)

- Kelly, Daniel. James Burnham and the Struggle for the World: A Life (2002)

- Kendall, Willmoore, and George W. Carey. "Towards a Definition of 'Conservatism." Journal of Politics 26 (May 1964): 406-22. in JSTOR

- Kirk, Russell. The Conservative Mind. Regnery Publishing; 7th edition (2001). highly influential history of ideas online at ACLS e-books

- Krugman, Paul. "Who Was Milton Friedman?" New York Review of Books Vol 54#2 Feb. 15, 2007 online version

- Lora, Ronald. Conservative Minds in America Greenwood, 1976.

- Lowi, Theodore J. The End of the Republican Era (1995) online review, by a liberal

- Meyer, Frank S. ed. What Is Conservatism? 1964.

- Murphy, Paul V. The Rebuke of History: The Southern Agrarians and American Conservative Thought (2001) excerpt and text search

- Nash, George. The Conservative Intellectual Movement in America Since 1945 (1978, 2006) influential history. excerpt and text search

- Nisbet, Robert A. Conservatism: Dream and Reality. U. of Minnesota Press, 1986.

- Ribuffo, Leo P. The Old Christian Right: The Protestant Far Right from the Great Depression to the Cold War. Temple University Press. 1983

- Rodgers, Marion Elizabeth. Mencken: The American Iconoclast (2005)

- Rossiter, Clinton. Conservatism in America. 2nd ed. 1982.

- Scotchie, Joseph. Barbarians in the Saddle: An Intellectual Biography of Richard M. Weaver (1997)

- Scotchie, Joseph. Street Corner Conservative: Patrick J. Buchanan and His Times (2004)

- Scotchie, Joseph. The Paleoconservatives: New Voices of the Old Right (1994)

- Smant, Kevin J. Principles and Heresies: Frank S. Meyer and the Shaping of the American Conservative Movement (2002)

- Stigler, George Joseph. Memoirs of an Unregulated Economist (1988), autobiography of leader of Chicago School of Economics

- Thorne; Melvin J. American Conservative Thought since World War II: The Core Ideas Greenwood: 1990

- Viereck; Peter Conservatism: from John Adams to Churchill 1956, 1978

Political activity: Before 1940

- Cheek Jr., H. Lee. Calhoun and Popular Rule: The Political Theory of the Disquisition and Discourse (2001). Stresses Calhoun's Republicanism online edition

- Lora, Ronald, and William Henry Longton. The Conservative Press in Twentieth-Century America (1999) online edition

- McDonald, Forrest. States' Rights and the Union: Imperium in Imperio, 1776-1876 (2002)

- Malsberger, John W. From Obstruction to Moderation: The Transformation of Senate Conservatism, 1938-1952 2000.

- Patterson, James. Congressional Conservatism and the New Deal: The Growth of the Conservative Coalition in Congress, 1933-39 (1967)

- Risjord. Norman K. The Old Republicans: Southern Conservatism in the Age of Jefferson (1965) online edition

- Wilensky, Norman N. Conservatives in the Progressive Era: The Taft Republicans of 1912 (1965).

Political activity: 1940-1990s

- Bader; John B. Taking the Initiative: Leadership Agendas in Congress and the "Contract with America" (1996) online edition

- Collins, Robert M. Transforming America: Politics and Culture During the Reagan Years, (2007) 320 pages. excerpt and text search

- Critchlow, Donald T. Phyllis Schlafly and Grassroots Conservatism: A Woman's Crusade (2005) excerpt and text search

- Dierenfield, Bruce J. Keeper of the Rules: Congressman Howard W. Smith of Virginia (1987), leader of the Conservative coalition in Congress

- Fergurson, Ernest B. Hard Right: The Rise of Jesse Helms, (1986), on the North Carolina Senator

- Fite, Gilbert. Richard B. Russell, Jr, Senator from Georgia (2002) leader of the Conservative coalition in Congress

- Goldberg, Robert Alan. Barry Goldwater (1995) excerpt and text search

- Hart, Jeffrey. The Making of the American Conservative Mind: The National Review and Its Times (2005)

- Himmelstein, Jerome and J. A. McRae Jr., "'Social Conservatism, New Republicans and the 1980 Election'", Public Opinion Quarterly, 48 (1984), 595-605.

- Koopman; Douglas L. Hostile Takeover: The House Republican Party, 1980-1995 Rowman & Littlefield, 1996

- Lora, Ronald, and William Henry Longton. The Conservative Press in Twentieth-Century America Greenwood Press, 1999 online edition

- Patterson, James T. Mr. Republican: A Biography of Robert A. Taft (1972)

- Pemberton, William E. Exit with Honor: The Life and Presidency of Ronald Reagan (1998) online edition

- Perlstein, Rick. Before the Storm: Barry Goldwater and the Unmaking of the American Consensus (2004) on 1964 excerpt and text search

- Phillips-Fein, Kim. Invisible Hands: The Making of the Conservative Movement from the New Deal to Reagan (2008)

- Reinhard, David W.; Republican Right since 1945 (1983) online edition

- Schuparra, Kurt. Triumph of the Right: The Rise of the California Conservative Movement, 1945-1966 (1998)

- Shelley II, Mack C. The Permanent Majority: The Conservative Coalition in the United States Congress (1983)

- Smith, Richard Norton. An Uncommon Man: The Triumph of Herbert Hoover (1994)

- Tanenhaus, Sam. Whittaker Chambers: A Biography (1997) excerpt and text search** Chambers, Whittaker, Witness (1952), a memoir his Communist years

Recent politics

- Berkowitz, Peter . Varieties of Conservatism In America (2004)

- Critchlow, Donald T. The Conservative Ascendancy: How the GOP Right Made Political History (2007)

- Cooper, Barry, Allan Kornberg, William Mishler, eds. The Resurgence of Conservatism in Anglo-American Democracies, Duke University Press, 1988 online edition

- Dunn, Charles W., ed. The Future of Conservatism: Conflict and Consensus in the Post-Reagan Era (2007). 10 essays; 156pp

- Friedelbaum, Stanley H. The Rehnquist Court: In Pursuit of Judicial Conservatism Greenwood Press, 1994 online edition

- Frohnen, Bruce et al eds. American Conservatism: An Encyclopedia (2006), the most detailed reference

- Frum, David. What's Right: The New Conservative Majority and the Remaking of America. 1996. online edition

- Micklethwait, John, and Adrian Wooldridge. The Right Nation, (2004) influential survey

- Rae; Nicol C. Conservative Reformers: The Republican Freshmen and the Lessons of the 104th Congress M. E. Sharpe, 1998

- Schoenwald; Jonathan . A Time for Choosing: The Rise of Modern American Conservatism (2002) online edition also online at ACLS e-books

- Tanner, Michael D. Leviathan on the Right: How Big-Government Conservativism Brought Down the Republican Revolution (2007) excerpt and text search

Neoconservatism

- Bloom, Allan. The Closing of the American Mind (1988)

- Dorrien, Gary. The Neoconservative Mind,

- Friedman, Murray. The Neoconservative Revolution: Jewish Intellectuals and the Shaping of Public Policy. Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Fukuyama, Francis. America at the Crossroads: Democracy, Power, and the Neoconservative Legacy, (2006)

- Gerson, Mark. The Neoconservative Vision: From the Cold War to Culture Wars (1997)

- Halper, Stefan & Clarke, Jonathan, America Alone: The Neo-Conservatives and the Global Order (Cambridge University Press, 2004) ISBN 0-521-83834-7

- Kristol, Irving. Neoconservatism: the Autobiography of an Idea,

- Murray, Douglas. Neoconservatism: Why We Need It,

- Steinfels, Peter. The Neoconservatives: The Men Who Are Changing America's Politics. (1979)

- Stelzer, Irwin. Neo-conservatism (2004)

- Stelzer, Irwin. The NeoCon Reader (2004)

Critical views from the left

- Bell, David. ed, The Radical Right. Doubleday 1963.

- Huntington, Samuel P. "Conservatism as an Ideology." American Political Science Review 52 (June 1957): 454-73.

- Coser Lewis A., and Irving Howe, eds. The New Conservatives: A Critique from the Left New American Library, 1976.

- Dean, John W. Conservatives Without Conscience (2006) excerpt and text search

- Diamond, Sara. Roads to Dominion: Right-Wing Movements and Political Power in the United States. (1995)

- Frank, Thomas. What's the Matter with Kansas?: How Conservatives Won the Heart of America (2005) excerpt and text search

- Lapham, Lewis H. "Tentacles of Rage" in Harper's, September 2004, p. 31-41.

- Martin, William. 1996. With God on Our Side: The Rise of the Religious Right in America, New York: Broadway Books.

- Nunberg, Geoffrey. Talking Right: How Conservatives Turned Liberalism into a Tax-Raising, Latte-Drinking, Sushi-Eating, Volvo-Driving, New York Times-Reading, Body-Piercing, Hollywood-Loving, Left-Wing Freak Show, (2006) excerpt ans text search

- Tanner, Michael D. Leviathan on the Right: How Big-Government Conservativism Brought Down the Republican Revolution, (2007) a libertarian critique from the CATO Institute excerpt and text search

Primary sources

- Buckley, William F., Jr., ed. Up from Liberalism (1958)

- Buckley, William F., Jr., ed. Did You Ever See a Dream Walking? American Conservative Thought in the 20th Century (1970)

- Gerson, Mark ed., The Essential Neo-Conservative Reader (1997))

- Irving Kristol, Neoconservatism: the Autobiography of an Idea,

- Schneider, Gregory L. ed. Conservatism in America Since 1930: A Reader (2003)

- Schweizer, Peter, and Wynton C. Hall, eds. Landmark Speeches of the American Conservative Movement (2007) excerpt and text search

- Stelzer, Irwin, ed. The NeoCon Reader (2005)

- Wolfe, Gregory. Right Minds: A Sourcebook of American Conservative Thought. (1987)

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ The word was originally used in the French Revolution. The British used it after 1839 to describe a major party. The first American usage is by Whigs who called themselves "Conservatives" in the late 1830s. Hans Sperber and Travis Trittschuh, American Political terms: An Historical Dictionary (1962) 94-97.

- ↑ Curtis, Bruce. "William Graham Sumner 'On the Concentration of Wealth.'" Journal of American History 1969 55(4): 823-832.

- ↑ Lapham 2004

- ↑ Samuel P. Huntington, "The Clash of Civilizations," Foreign Affairs Summer 1993, v72, n3, p22-50, online version.

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ Richard Hofstadter, Anit-Intellectualism in American Life (1963)

- ↑ Friedrich August von Hayek, 1889-1992

- ↑ Milton Friedman, 1912-2006

- ↑ Ludwig Edler von Mises, 1881-1973

- ↑ Safire 1994

- ↑ Robert Taft, Taft Papers 3:313

- ↑ [5]

- ↑ See [6]

- ↑ See [7]

- ↑ see [8]

- ↑ see [9] and [10]

- ↑ See [11] and [12]

- ↑ See People for the American Way and Nobel prizewinners on creation science.

- ↑ Barbara R. Bergmann, In Defense of Affirmative Action, Basic Books, 1997, ISBN 0-465-09834-7

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- Economics Workgroup

- Politics Workgroup

- Sociology Workgroup

- American politics since 1945 Subgroup

- Articles written in British English

- Advanced Articles written in British English

- All Content

- Economics Content

- Politics Content

- Sociology Content

- American politics since 1945 tag