Julius Caesar

Gaius Iulius Caesar (anglicized: Gaius Julius Caesar; born 13 July[1] 100 BC;[2] died 15 March 44 BC; Latin pronounciation: ['gaːjʊs 'juːlijʊs 'kaɪ̯sar], English pronounciation: ['gaɪəs 'dʒuːliəs 'siːzəɹ]) was an aristocrat, politician and general of the late Roman Republic, and played a key role in the transformation of the Republic into the Roman Empire. He rose through the ranks of Roman elected offices to reach the consulship, and formed an unofficial, and controversial, triumvirate with Pompey the Great and Marcus Licinius Crassus which dominated Roman politics for several years. As a proconsul, he conquered Gaul and made expeditions to Britain and Germania. After the collapse of the triumvirate, he fought and won a civil war against the Senate and his former colleague Pompey, became the sole ruler of the Roman world, and was proclaimed Dictator in perpetuity. He left behind his own Commentaries on his wars in Gaul and the civil war, with supplementary books written by his supporters. He was assassinated by a group of senators hoping to restore the normal working of the Republic, but his death ushered in thirteen more years of civil war. Ultimately, his designated heir, Augustus, would establish permanent autocratic rule.

Biography

Early life

Caesar grew up in a patrician family which had come to political prominence during his father's generation. Two relatives had been consuls in the 90s BC, and Caesar's father, also called Gaius Julius Caesar, had been praetor and governor of Asia, and was brother-in-law to Gaius Marius, one of the most prominent men in the Republic. His mother, Aurelia, came from an influential family, the Aurelii Cottae.[3]

Rome already ruled much of the Mediterranean, but was politically unstable and faced external threats. The Social War against her Italian allies, over the issue of Roman citizenship and the spoils of conquest, was fought from 91 to 88 BC, and Mithridates of Pontus was pressing her eastern provinces. With the Social War settled, Lucius Cornelius Sulla was appointed to lead the campaign against Mithridates, until a tribune passed a law stripping him of his command and transferring it to Marius. Sulla, who was with his troops near Naples, marched on Rome, forced Marius into exile, and left on campaign. Once he was gone, Marius retook the city, with the help of Lucius Cornelius Cinna, and took bloody revenge on Sulla's supporters. One of those killed was Lucius Cornelius Merula, the Flamen Dialis or priest of Jupiter. Marius died in 85 BC, leaving Cinna in control of the city.[4]

In 84 BC Caesar's father died suddenly while putting on his shoes one morning,[5] leaving the sixteen-year-old Caesar as head of the family. He was nominated to replace Merula as Flamen Dialis, and broke off his engagement to Cossutia, the daughter of a wealthy equestrian, to marry Cinna's daughter Cornelia.[6]

Having brought Mithridates to terms, Sulla returned to Italy, and civil war resumed. Cinna was killed in a mutiny of his own troops. Sulla retook Rome in November 82 BC, had himself appointed dictator, and embarked on a campaign of political murder that dwarfed even Marius's purges.[7] Caesar, as Marius's nephew and Cinna's son-in-law, was firmly identified with Sulla's enemies. He was stripped of his inheritance and his priesthood, but refused to divorce Cornelia and was forced to go into hiding. His mother's family and the Vestal Virgins intervened on his behalf, and Sulla reluctantly lifted the threat against him, remarking that there were "many Mariuses" in the young Caesar.[8]

Caesar did not return to Rome, but instead joined the army. He served in Asia, his father's old province, and Cilicia, and won the corona civica for his part in the siege of Mytilene. On a mission to Bithynia, he spent so long at the court of king Nicomedes that rumours of an affair with the king arose, which would persist for the rest of his life.[9]

He returned to Rome after Sulla's death in 78 BC and began to use his oratorical talents in the courts. In 75 BC he travelled to Rhodes to study under Apollonius Molon, but on his way there was kidnapped by pirates. After he was released on payment of a ransom, he pursued the pirates in a small fleet and had them crucified on his own authority.[10]

Political career

Caesar returned to Rome and began to climb the political ladder. He was elected military tribune, the first step in the cursus honorum, in 72 or 71 BC, around the time of the war against Spartacus, although it is not known what part, if any, he played in it. In 69 both his wife Cornelia and his aunt Julia, Marius's widow, died. Caesar delivered their funeral orations, and included images of Marius, unseen since Sulla's dictatorship, in Julia's funeral procession. He was elected quaestor for the same year, and served his year in office in Hispania. On his return to Rome he married Pompeia, a granddaughter of Sulla.[11] However, he continued to rehabilitate Marius's reputation while aedile in 65 BC, restoring the trophies of his victories, and brought prosecutions against those who had benefited financially from Sulla's proscriptions. He spent a great deal of borrowed money on public works and games, outshining, not for the last time, his colleague Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus.[12] During this period he was suspected of involvement in a number of attempted coups, one involving Marcus Licinius Crassus,[13] and supported the extraordinary commands given to Pompey, against the Cilician pirates in 67 BC,[14] and against Mithridates the following year.[15]

63 BC was an eventful year for Caesar. He persuaded a tribune, Titus Labienus, to bring a prosecution against Gaius Rabirius. In 100 BC Lucius Appuleius Saturninus, a tribune and ally of Marius, had been declared a public enemy by the Senate, and Marius had been obliged to besiege him in the Senate house. He had promised Saturninus and his followers that their lives would be spared if they surrendered, but instead they were stoned to death with roof tiles by a crowd that included senators.[16] Rabirius was accused of the crime, and as by Roman law a tribune's person was sacrosanct, he was tried for perduellio (treason). He was defended by Cicero and Quintus Hortensius, the two foremost advocates of the day, but Caesar himself was one of the two judges, and Rabirius was convicted. But while he was exercising his right of appeal to the people, the praetor Quintus Caecilius Metellus Celer adjourned the assembly by taking down the military flag from the Janiculum hill. Labienus could have resumed the prosecution at a later session, but did not do so: Caesar's point had been made, and the matter was allowed to drop.[17] Labienus would remain an important ally of Caesar over the next decade.

The same year, Caesar ran for election to the post of Pontifex Maximus, chief priest of the Roman state religion, after the death of Quintus Caecilius Metellus Pius, who had been appointed to the post by Sulla. He ran against two former consuls, Quintus Lutatius Catulus and Publius Servilius Vatia Isauricus. There were accusations of bribery by all sides. Caesar is said to have told his mother on the morning of the election that he would return as Pontifex Maximus or not at all, expecting to be forced into exile by the enormous debts he had run up to fund his campaign. In the event he won comfortably, despite his opponents' greater experience and standing.[18] The post came with an official residence on the Via Sacra.[19]

When Cicero, who was consul that year, exposed Catiline's conspiracy to seize control of the republic, Catulus and others accused Caesar of involvement in the plot.[20] During the debate in the Senate on how to deal with the conspirators, Caesar was passed a note. Marcus Porcius Cato, who would become his most implacable political opponent, accused him of corresponding with the conspirators, and demanded that the message be read aloud. Caesar passed him the note, which, embarrassingly, turned out to be a love letter from Cato's half-sister Servilia. Caesar argued persuasively against the death penalty for the conspirators, proposing life imprisonment instead, but a speech by Cato proved decisive, and the conspirators were executed.[21]

While praetor in 62 BC Caesar supported Metellus Celer, now tribune, in proposing controversial legislation, and the pair were so obstinate they were suspended from office by the Senate. Caesar attempted to continue to perform his duties, only giving way when violence was threatened. The Senate was persuaded to reinstate him after he quelled public demonstrations in his favour.[22] A commission had been set up to investigate Catiline's conspiracy, and Caesar was again accused of complicity, but, relying on Cicero's evidence that he had reported what he knew of the plot voluntarily, he was cleared, and not only one of his accusers, but also one of the commissioners, were sent to prison.[23]

That year the festival of the Bona Dea ("good goddess") was held at Caesar's house. No men were permitted to attend, but a young patrician named Publius Clodius Pulcher managed to gain admittance disguised as a woman, apparently for the purpose of seducing Caesar's wife Pompeia. He was caught and prosecuted for sacrilege. Clodius was acquitted after Caesar gave no evidence against him. Nevertheless, Caesar divorced Pompeia, saying that "my wife ought not even to be under suspicion."[24]

After his praetorship, Caesar was sent as propraetor to govern Hispania Ulterior (Outer Iberia), but he was still in considerable debt, and needed to satisfy his creditors before he could leave. He turned to Marcus Licinius Crassus, one of Rome's richest men. In return for political support in his implacable opposition to the interests of Pompey, Crassus paid some of Caesar's debts and acted as guarantor for others. Even so, to avoid becoming a private citizen and open to prosecution for his debts, Caesar left for his province before his praetorship had ended. In Hispania he conquered the Callaici and Lusitani and was hailed as imperator by his troops, reformed the law regarding debts, and completed his governorship in high esteem.[25]

Being hailed as imperator entitled him to receive a triumph upon his return to Rome. However, he also wanted to stand for consul, the most senior magistracy in the republic. If he were to celebrate a triumph, he would have to remain a soldier and stay outside the city until the ceremony, but to stand for election he would need to lay down his command and enter Rome as a private citizen. He could not do both in the time available. He asked the senate for permission to stand in absentia, but Cato blocked the proposal. Faced with the choice between a triumph and the consulship, Caesar chose the consulship.[26]

The election was dirty. There were three candidates: Caesar, Lucius Lucceius and Marcus Calpurnius Bibulus, who had been aedile with Caesar several years earlier. Caesar canvassed Cicero for support, and made an alliance with the wealthy Lucceius, but the establishment threw its financial weight behind the conservative Bibulus, and even Cato, with his reputation for incorruptibility, is said to have resorted to bribery in his favour. Caesar and Bibulus were elected as consuls for 59 BC.[27]

Caesar was already in Crassus's political debt, but he also made overtures to Pompey, who was unsuccessfully fighting the Senate for ratification of his eastern settlements and farmland for his veterans. Pompey and Crassus had been at odds since they were consuls together in 70 BC, and Caesar knew if he allied himself with one he would lose the support of the other, so he endeavoured to reconcile them. Between the three of them, they had enough money and political influence to control public business. This informal alliance, known as the First Triumvirate (rule of three men), was cemented by the marriage of Pompey to Caesar's daughter Julia.[28] Caesar also married again, this time Calpurnia, daughter of Lucius Calpurnius Piso Caesoninus, who was elected to the consulship for the following year.[29]

Caesar proposed a law for the redistribution of public lands to the poor, a proposal supported by Pompey, by force of arms if need be, and by Crassus, making the triumvirate public. Pompey filled the city with soldiers, and the triumvirate's opponents were intimidated. Bibulus attempted to declare the omens unfavourable and thus void the new law, but was driven from the forum by Caesar's armed supporters. His lictors had their fasces broken, two tribunes accompanying him were wounded, and Bibulus himself had a bucket of excrement thrown over him. In fear of his life, he retired to his house for the rest of the year, issuing occasional proclamations of bad omens. These attempts to obstruct Caesar's legislation proved ineffective. Roman satirists ever after referred to the year as "the consulship of Julius and Caesar".[30]

When Caesar and Bibulus were first elected, the aristocracy tried to limit Caesar's future power by allotting the woods and pastures of Italy, rather than governorship of a province, as their proconsular duties after their year of office was over.[31] With the help of Piso and Pompey, Caesar later had this overturned, and was instead appointed to govern Cisalpine Gaul (northern Italy) and Illyricum (the western Balkans), with Transalpine Gaul (southern France) later added, giving him command of four legions. His term of office, and thus his immunity from prosecution, was set at five years, rather than the usual one.[32] When his consulship ended, Caesar narrowly avoided prosecution for the irregularities of his year in office, and quickly left for his province.[33]

The conquest of Gaul

to come

Civil war

to come

Dictatorship

to come

Assassination

to come

Legacy

to come

Etymologies of Caesar's name

The cognomen Caesar

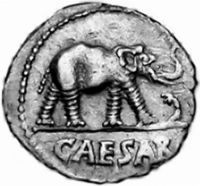

The suffix –ar was highly unusual for the Latin language, which might imply a non-Latin origin of the name. The etymology of the name Caesar is still unknown and was subject to many interpretations even in antiquity. Caesar himself propagated the derivation from the Moorish or Punic word for "elephant",[34] thereby following the claims of his family that they inherited the cognomen from an ancestor, who had received the name after killing an elephant, possibly during the first Punic War. Since the Gauls came to know the elephant through the Punic commander Hannibal, it is possible that the animal was also known under the name caesar in Gaul. Caesar displayed an elephant above the name CAESAR on his first denarius, which he probably had minted while still in Gallia Cisalpina. Apart from using the elephant as a claim for extraordinary political power in Rome,[35] the coin is an unmasked allusion to the etymology of the name and directly identifies Caesar with the elephant, because the animal treads a Gallic serpent-horn, the carnyx, as a symbolic depiction of Caesar's own victory.[36] Polyaenus tells an unlikely story about Caesar using an armoured elephant during his expeditions to Britain,[37] which may derive from a confusion with Claudius's use of elephants in his conquest of Britain in AD 43,[38] but may be connected with this interpretation of Caesar's name.

Several other interpretations were propagated in antiquity:

- a caesis oculis[39] ("because of the blue [or: grey] eyes"): Caesar's eyes were black,[40] but this interpretation might have been created as part of the anti-Caesarian propaganda, because Caesar's early adversary, the dictator Sulla had blue eyes.

- a caesaries ("because of the hair")[41]: Since Caesar was balding, this interpretation might have been part of the anti-Caesarian mockery.

- a caeso matris utero ("born by Caesarean section")[42]: In theory this might go back to an unknown Julian ancestor who was born in this way. On the other hand it could also have been part of the anti-Caesarian propaganda, because in the eyes of the Republicans Caesar had defiled the Roman "motherland", which was also reported for one of Caesar's dreams, in which he committed incest with his mother, i.e. the earth.[43]

The nomen gentile Iulius

coming soon

Literary work

to come

List of Caesar's literary works

Works preserved in their entirety

- Commentarii de bello Gallico (Commentaries on the Gallic war)

- Commentarii de bello civili (Commentaries on the civil war)

- De Bello Hispaniensi (Caesar's authorship doubted)

- De Bello Africo (Caesar's authorship doubted)

- De Bello Alexandrino (Caesar's authorship doubted)

Works preserved in fragments

- Orations:

- Orationes in Cn. Cornelium Dolabellam

- Suasio Legis Plautiae

- Laudatio Iuliae amitae

- Ad milites in Africa

- Apud milites de commodis eorum

- Pro Bithynis

- De analogia ad M. Tullium Ciceronem

- Anticatonis Libri II

- Carmina et prolusiones

- Epistulae ad Ciceronem

- Epistulae ad familiares

Lost works

- several poems from Caesar's youth (including love poems), which were probably lost because of a partial damnatio memoriae declared by Caesar's successor Augustus, among them:

- Iter ("The Way")

Cultural depictions

to come

References

- ↑ Due to the collision with the principal day of the ludi Apollinaris, the feast day in honor of Caesar's birth was moved from the 13th to the 12th of July in the Roman fasti after Caesar's consecratio as Divus Iulius, since according to a Sibylline oracle it was not permitted to hold a festival for any other god than Apollo on July 13th. Cf. Cassius Dio: Roman History 47.18.6; see also Georg Wissowa (Religion und Kultus der Römer, 1912/1971), Matthias Gelzer (Caesar, 1959/1983), Stefan Weinstock (Divus Julius, 1971/2004) et al.

- ↑ The most widely accepted year of birth. A case was made for 102 BC (cf. Theodor Mommsen: Römische Geschichte III 16.1, Römisches Staatsrecht I 568.2 & 569.2; pro: T. Rice Holmes: The Roman Republic, 1923, I 436–442), but was quickly rejected by Karl Nipperdey (Die leges annales. Leipzig 1865) and is generally viewed as incorrect.

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 1; Plutarch, Caesar 1, Marius 6; Inscriptiones Italiae, 13.3.51-52

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1:34-75; Plutarch, Marius 32-46, Sulla 6-10; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.15-22; Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History 5; Florus, Epitome of Roman History 2:6, 2:9

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.54; Suetonius, Julius 1

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 1; Plutarch, Caesar 1; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.41

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 1.76-102; Plutarch, Sulla 24-33; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.23-28; Eutropius, Abridgement of Roman History 5; Florus, Epitome of Roman History 2:9

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 1; Suetonius, Julius 1

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 2-3; Plutarch, Caesar 2-3; Cassius Dio, Roman History 43.20

- ↑ According to Suetonius (Julius 3-4). Plutarch (Caesar 1.8-3) relates these events in a different order; Velleius Paterculus (Roman History 41.3-42), tells the story of Caesar's kidnapping, but does not give a precise chronology.

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 5-8; Plutarch, Caesar 5; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 9-11; Plutarch, Caesar 5.6-6; Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.8, 10

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 9

- ↑ Plutarch, Pompey 25

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 36.42

- ↑ Appian, Civil Wars 32-33; Plutarch, Marius 29-30

- ↑ Cicero, For Gaius Rabirius; Cassius Dio, Roman History 26-28

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.43; Plutarch, Caesar 7; Suetonius, Julius 13

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 46

- ↑ Sallust, Catiline War 49

- ↑ Cicero, Against Catiline 4.7-9; Sallust, Catiline War 50-55; Plutarch, Caesar 7.5-8.3, Cicero 20-21, Cato the Younger 22-24; Suetonius, Julius 14

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 16

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 17

- ↑ Cicero, Letters to Atticus 1.12, 1.13, 1.14; Plutarch, Caesar 9-10; Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.45

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 11-12; Suetonius, Julius 18.1

- ↑ Plutarch, Julius 13; Suetonius, Julius 18.2

- ↑ Plutarch, Caesar 13-14; Suetonius 19

- ↑ Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.1, 2.3], 2.17; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2.44; Plutarch, Caesar 13-14, Pompey 47, Crassus 14; Suetonius, Julius 19.2; Cassius Dio, Roman History 37.54-58

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 21

- ↑ Cicero, Letters to Atticus 2.15, 2.16, 2.17, 2.18, 2.19, 2.20, 2.21; Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 44.4; Plutarch, Caesar 14, Pompey 47-48, Cato the Younger 32-33; Cassius Dio, Roman History 38.1-8

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 19.2

- ↑ Velleius Paterculus, Roman History 2:44.4; Plutarch, Caesar 14.10, Crassus 14.3, Pompey 48, Cato the Younger 33.3; Suetonius, Julius 22; Cassius Dio, Roman History 38:8.5

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 23

- ↑ Historia Augusta, Aelius 2.3; Servius, Commentary on the Aeneid 1.286 i.a.; cp. Pauly-Wissowa RE X 464sq;

- ↑ Artemidorus established that the elephant, undoubtedly a symbol of honor (and arrogance), denoted a δεσποτης ("lord"), a βασιλευς ("king") or a και ανηρ μεγιστος ("man in high authority") on the Italian mainland. Therefore the coin would have to be seen as a presage for Caesar's future dominion. (From Stevenson et al.: A Dictionary of Roman Coins: Republican and Imperial. London 1889.)

- ↑ Cf. Christoph Battenberg: Pompeius und Caesar: Persönlichkeit und Programm in ihrer Münzpropaganda (Marburg/Lahn 1980). Furthermore the elephant was a counter-symbol against the gens Caecilia, whose heralding symbol was the elephant, attesting victories gained by the Metelli in Sicily (250 BC) and Macedonia (148 BC). In 49 BC Metellus Scipio had ordered Caesar to surrender his army, although Pompeius was levying troops, and the Metelli had also tried to stop Caesar from confiscating the state treasury in the temple of Saturn, where Caesar eventually had his coins struck. Therefore Caesar's propaganda communicated not only the taking of the treasure but also the taking of his enemies' symbol and placed his own victory over Gaul above the Metellan victories.

- ↑ Polyaenus, Stratagems 8:23.5

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History 60:21

- ↑ Spartianus: Historia Augusta (Aelius) 2.3

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 45

- ↑ According to Sextus Pompeius Festus.

- ↑ Pliny the Elder, Natural History 7.7

- ↑ Suetonius, Julius 7; Cassius Dio 37.52.2