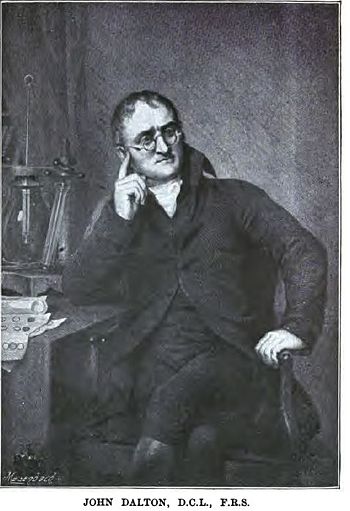

John Dalton

|

Note: Text in font-color Blue link to articles in Citizendium; text in font-color Maroon link to articles not yet started; |

|

In the vestibule of the Manchester Town Hall are placed two life-sized marble statues facing each other. One of these is that of John Dalton, by Chantrey; the other that of James Prescott Joule, by Gilbert. Thus honour is done to Manchester's two greatest sons - to Dalton, the founder of modern Chemistry and of the Atomic Theory, and the discoverer of the laws of chemical-combining proportions; to Joule, the founder of modern Physics and the discoverer of the law of the Conservation of Energy. The one gave to the world the final and satisfactory proof of the great principle, long surmised and often dwelt upon, that in every kind of chemical change no loss of matter occurs; the other proved that in all the varied modes of physical change no loss of energy takes place. Dalton, by determining the relative weights of the atoms which take part in chemical change, proved that every such change - whether from visible to invisible, from solid to liquid, or from liquid to gas - can be represented quantitatively by a chemical equation; and he created the Atomic Theory of Chemistry by which these changes are explained. Joule, by exact experiment, proved the truth of the same statement for the different forms of energy. —Sir Henry Roscoe, John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry. 1895. [1] |

John Dalton (1766-1844), an English scientist, one of the founders of modern chemistry and meteorology, taught mathematics and physical sciences at New College, Manchester, having begun his teaching career at the age of 12 years as a co-teacher with his older brother.[2] [3] Dalton inferred from experimental studies of evaporation an atomic theory of matter, which the ancient Greeks had first suggested, but which Dalton provided experimental support for and extended by discovering that all elements did not have the same mass and size.

He developed a table of weights of the atoms of different elements, a law of partial pressures (Dalton's law) — "....where the pressure exerted by each gas in a mixture [of gases] is independent of the pressure exerted by the other gases, and where the total pressure is the sum of the pressures of each gas."[4] — and a law about the combining of elements called the law of multiple proportions. He was color-blind and studied that affliction, also known as Daltonism.

Dalton's law of multiple proportions: If two elements form more than one compound, the weights in different compounds of an element are ratios of integral numbers. For instance, consider the elements nitrogen and oxygen. The element oxygen occurs in the compounds NO and NO2. The ratio of oxygen weights (1:2) in these compounds contains the integral numbers 1 and 2. (Note that in modern chemistry the concept "weight", used by Dalton, is replaced by "number of atoms". Now we say that the ratio of numbers of O-atoms in different NOx compounds is a rational number. Or, by extension of Dalton's law of multiple proportions, the subscripts m, n, k, ... in a compound AmBnCk⋅⋅⋅ are integral numbers.) This law led Dalton to take the mass of the lightest element, hydrogen, as unit of atomic mass.

Early life

References and notes cited in text

|

Many citations to articles listed here include links to full-text — in font-color blue. Accessing full-text may require personal or institutional subscription to the source. Nevertheless, many do offer free full-text, and if not, usually offer text or links that show the abstracts of the articles. Links to books variously may open to full-text, or to the publishers' description of the book with or without downloadable selected chapters, reviews, and table of contents. Books with links to Google Books often offer extensive previews of the books' text. |

- ↑ Roscoe HE. (1895) John Dalton and the Rise of Modern Chemistry. New York: Macmillan & Co.

- ↑ John Dalton. Free full-text article from Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Millington JP. (1906) John Dalton. E.P. Dutton & Co.: New York. Free full-text of book by former scholar of Christ's College, Cambridge.

- ↑ John Dalton. Chemical Achievers Website.