Human papilloma virus (HPV)

| Human papilloma virus | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Virus classification | ||||||

| ||||||

| Vectors | ||||||

|

human |

Description and significance

Papillomaviruses are nonenveloped DNA viruses. These viruses are diverse, but all can infect the skin and mucosal tissues of a many vertebrate species, including humans.[1] A group of genital mucosotropic human papilloma virus (HPV) types are etiologic agents responsible for virtually all cases of cervical cancer, as well as a substantial fraction of other ano-genital and head-and-neck cancers (reviewed in [1]). Cancer-associated genital HPV types, as well as another subset of HPV types associated with the development of benign genital warts (condyloma accuminata), are generally transmitted through sexual contact. Infection with genital HPV types is very common, with an estimated lifetime risk of infection of about 75% [2]. Although most genital HPV infections are subclinical and self-limiting, a subset of persistently infected individuals have lesions that progress to premalignancy or cancer.

Genome structure

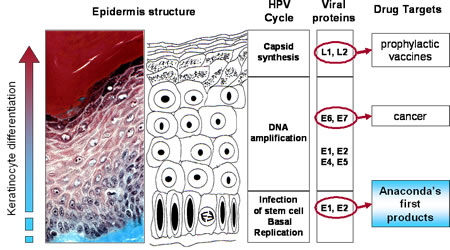

The HPV genome is a circular, double stranded DNA virus of approximately 8,000 base pairs and made up of 40-50% Guanine and Cytosine base pairs. All Papillomavirus genes are coded in one of the two DNA strands, using three forward reading frames, and alternative splicing for the individual expression of each gene. Papillomaviruses have the same general genomic organization. It consists of 8 open reading frames(ORF) all located on the same strand. These ORFs are designated either early (E) or late(L). The early ORFs-E1,E2,E4,E5,E6,and E7-code for nonstructural regulatory proteins. The E3 ORF does not code for a protein, and the E8 ORF has been identified only in bovine Papillomaviruses. The late ORFs-L1 and L2-code for capsid proteins. A 1-Kb non-coding region known as the upstream regulatory region (URR), lies between the early and late ORFs. The URR includes the origin of replication (ori), the E6/E7 gene promoter, and enhancers and silencers.[2]

Natural Host:

The only known host for HPV are Humans.

Discovery and Link to Cancer

In the early 1980s German Virologist Harold Zur Hausen discovered the link between cervical cancer and HPV. Using Southern Blot Hybridization, he went against the prevailing notion at the time that herpes simplex virus caused cervical cancer and discovered in fact that HPV DNA was present in the cervical tumors he tested. He named the first strain he discovered HPV-16. When another strain was discovered in about half the tumors he tested he named it HPV-18. His groundbreaking discovery led to the development of a vaccine and he was recognized with the 2008 Nobel Prize for physiology or medicine.[3]

Interesting Features:

It is extremely difficult to grow HPV in tissue culture and laboratory animals. Currently, this has not been done successfully. However, techniques such as polymerase chain reaction (PCR) are used to differentiate between different types. A distinct HPV type is defined as having less than 90% DNA base-pair homology with another identified HPV type.[4]

How does this organism cause disease?

HPV can infect the stratified squamous epithelium and nonkeratinized epithelium (i.e mouth, upper airway, vagina, cervix, and anal canal). HPV can also induce tumors in other tissues such as the conjunctiva, lachrymal sac, nasal passages, bronchi, esophagus cervical glandular tissue, and the bladder. The cellular receptors suggested in virus binding including a6 Integrin and heparin sulfate glycosomaminoglycans, have been identified on keratinocytes. HPV can also be found near sites of infection as well. The vast majority of HPV infections are latent(asymptomatic).[5]

Transmission

HPV is released from the sloughing off of the superficial keratinocytes of the infected area.. Cutaneous warts are spread through personal contact with infected tissue or through contact with contaminated surfaces or objects. Genital HPV is transmitted through sexual contact. Use of heated swimming pools or of communal baths are activities that can promote the acquisition of plantar warts. People who work with meat poultry, or fish are uniquely prone to had warts; and up to 50% are infected. The predominant strain in these cases is HPV-7.[6]

Cancer and latency

HPV-induced malignant transformation appears to be the result of a complex series of events that are independent of viral reproduction. In latency, histopathologic changes are absent and no viral particles are produced. Although the vast majority of HPV infections are latent, the viral and cellular factors that abrogate, induce and maintain latency are unknown. Integration of HPV DNA into the host genome seems to be associated with the progression of neoplasia to cancer. Possible sites of viral integration in the host genome are numerous and may exist on a variety of chromosomes and in proximity to cellular oncogenes. Integration results in the disruption, deletion or inactivation of the E2 ORF. Integration may also disrupt other viral genes but E6, 7 are usually spared.[7]

Current Research:

Mothers’ and Adolescents’ Beliefs about Risk Compensation following HPV Vaccination

In the United Kingdom, HPV vaccination is offered to girls aged 12 to 13 years old with a catch-up program for girls up to 18. In the US this suggestion has been met with opposition from religious groups who argue that it will encourage promiscuity, thus leading to increased teenage pregnancy and infertility. This study determines the effect of what is called Risk Compensation. Risk Compensation is the theory that individuals who know themselves to be protected from some form of infection will engage in behavior that is in accordance within a target level of risk they believe to be acceptable. Therefore, since young girls know that they will be protected, they might engage in more risky sexual activity. What they found was that one-third of girls thought that changes in sexual behavior as a result of HPV vaccination are possible in relation to ‘‘other girls,’’ but a smaller number of girls believe it will change their own sexual activities. The study concludes that more research will need to be done when the vaccine is actually administered at which point similar tests should be done to determine the risk compensation. The reason why it is important to determine risk compensation is to ease parental resistance towards vaccinating their children. [8]

An HPV 16 L1-based chimeric human papilloma virus-like particles containing a string of epitopes produced in plants is able to elicit humoral and cytotoxic T-cell activity in mice

Though there two types of prophylactic are currently marketed, the cost of the vaccines limit its widespread use in third world countries. One of the ways in which these vaccines can be made more affordable is by obtaining the immunogens from plants. In this study, HPV 16 VLPs containing L1 fused to a string of epitopes from the E6 and E7 proteins were expressed in tomato plants. Tomato lines expressing either L1 alone or the L1-E6/E7 particles were grown. The Chimeric VLPs were able to fully assemble in tomato cells. To test whether these VLPs produce an immune response they were injected into mice. The result was the production of Neutralizing antibodies against the viral particle and cytotoxic T-lymphocytes activity against the epitopes.[9]

Epidemiology

23% of women attending sexually transmitted disease, family planning, and primary care outpatient clinics in the United States of America may be positive for high-risk HPV.[10] Geographic distribution of HPV is limited. Geographic disparities in the prevalence of common warts can be seen within individual countries. A worldwide survey of HPV types showed that HPV-16 is the most prevalent type(50%) overall, followed by HPV-18(14%), HPV-45(8%) and HPV-31(5%) But notable geographic locations exist, particularly among the less common HPV types. HPV infections are endemic and no seasonality is recognized in the acquisition of HPV or in the expression of HPV diseases. The Prevalence of cervical HPV in women ranges from about 5-45% in Western Countries. These rates peak in young adults by their 3rd decade. Multiple HPV infections occur in 20-30% of HPV infected women.Hand warts represent 70% of all cutaneous warts and are mostly a childhood disease. The prevalence of common warts ranges from 0.8-22%. Plantar warts compose up to a third of cutaneous warts and are found in a wider age group, primarily in adolescents and young adults. Flat or juvenile warts constitute 4-8% of cutaneous warts with a peak prevalence among 10-12 yr olds.[11]

Genital HPV disease: There are estimated to be ~5.5million new cases a year in the US, making it the most commonly acquired sexually transmitted disease. At least 20 million people are believed to be actively infected in the US, and it is estimated that 75% of the population have been infected at one time. The prevalence of condyloma acuminatum (anal warts) is estimated to be 1% in the general population. HPV infection causes a vast majority of cervical cancer and types 16 and 18 are responsible for 70% of cases. Incidence rate increases directly with number of sexual partners. Recurrent respiratory papillomatosis: The age of onset has a bimodal distribution which includes young adults an young children but not the elderly. This disease is mainly associated with HPV6 and 11. Affected children are often delivered vaginally by teenage mothers with anogenital warts. For the adult-onset form, patients have a large number of lifetime sexual partners and a high frequency of practicing oral sex. Anogenital warts: About 2/3 of the sexual partners of persons with anogenital warts will develop the disease within 2 years. The risk of developing genital warts is most strongly and directly linked to the lifetime number of sexual partners.[12][13]

Prevention

I vitro studies show that carrageenan, extracted from red algae and commercially used to thicken products including sexual lubricants and infant formulas, is a potent inhibitor of HPV infection.[14] Pap smears should be acquired regularly, and those who smoke may be at a higher risk. Wearing a condom is also very important in preventing the spread of HPV.

HPV Vaccine

The HPV vaccine can reduce the incidence of high-grade cervical intraepithelial neoplasia[15] and HPV-associated anogenital disease[16].

Current Vaccines use Virus Like Particles(VLPs) made from recombinant viral coat proteins. There are currently two different vaccines available for prevention of HPV: Gardasil and Cervarix. Both vaccines protect against the two types responsible for most cervical cancers; 16 and 18. Gardasil also protects against genital warts;mostly caused by types 6 and 11[17]. However, these vaccines cannot inhibit an infection that has already occurred.

In the United States of America, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommends vaccination of females starting at aged 11 - 12 years.[18]

References

- ↑ Index of Viruses - Papillomaviruses (2006). In: ICTVdB - The Universal Virus Database, version 4. Büchen-Osmond, C (Ed), Columbia University, New York, USA. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/ICTVdb/Ictv/fs_index.htm

- ↑ O'Connor, Mark J.; Walter Stünkel, Holger Zimmermann, Choon-Heng Koh, and Hans-Ulrich Bernard (December 1998). "A Novel YY1-Independent Silencer Represses the Activity of the Human Papillomavirus Type 16 Enhancer". Journal of Virology 72 (12): 10083–10092. PMC110540. Retrieved on 26 October 2013.

- ↑ http://www.sciencenews.org/view/generic/id/37255/title/Nobel_Prize_in_medicine_given_for_HIV,_HPV_discoveries

- ↑ http://www.nursingtimes.net/the-epidemiology-and-burden-of-hpv-disease/1839049.article

- ↑ Watson, Richard A. (Summer 2005). "Human Papillomavirus: Confronting the Epidemic—A Urologist's Perspective". Reviews in Urology 7 (3): 135–144. PMC1477576. Retrieved on 26 October 2013.

- ↑ http://goliath.ecnext.com/coms2/gi_0199-6068231/Epidemiology-and-natural-history-of.html

- ↑ http://www.brown.edu/Courses/Bio_160/Projects1999/hpv/path.html

- ↑ Marlow, Laura, et al.. "Mothers’ and Adolescents’ Beliefs about Risk Compensation following HPV Vaccination." Journal of Adolescent Health (2009): Print.

- ↑ De la Rosa, GP. "An HPV 16 L1-based chimeric human papilloma virus-like particles." VIROLOGY JOURNAL 6 (2009): Print.

- ↑ Datta, S. D., Koutsky, L. A., Ratelle, S., Unger, E. R., Shlay, J., McClain, T., et al. (2008). Human Papillomavirus Infection and Cervical Cytology in Women Screened for Cervical Cancer in the United States, 2003-2005. Ann Intern Med, 148(7), 493-500.

- ↑ http://www.brown.edu/Courses/Bio_160/Projects1999/hpv/epidem1.html

- ↑ http://www.spokane.wsu.edu/research&service/ahec/content/docs/Syllabus%20Versions/Post%20PCU-Newkirk%20HPV2.pdf

- ↑ http://www.nursingtimes.net/the-epidemiology-and-burden-of-hpv-disease/1839049.article

- ↑ Buck CB, Thompson CD, Roberts JN, Müller M, Lowy DR, Schiller JT (2006). "Carrageenan is a potent inhibitor of papillomavirus infection". PLoS Pathog. 2 (7): e69. DOI:10.1371/journal.ppat.0020069. PMID 16839203. Research Blogging.

- ↑ The FUTURE II Study Group (May 2007). "Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent high-grade cervical lesions". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (19): 1915–27. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa061741. PMID 17494925. Research Blogging. ACP Journal Club review JournalWatch review

- ↑ Garland SM, Hernandez-Avila M, Wheeler CM, et al for the Females United to Unilaterally Reduce Endo/Ectocervical Disease (FUTURE) I Investigators (May 2007). "Quadrivalent vaccine against human papillomavirus to prevent anogenital diseases". N. Engl. J. Med. 356 (19): 1928–43. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa061760. PMID 17494926. Research Blogging. ACP Journal Club review JournalWatch review

- ↑ Vaccines and Preventable Diseases: HPV Vaccine - Questions & Answers. National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases (20 July 2012). Retrieved on 26 October 2013.

- ↑ Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) (March 12, 2007). Quadrivalent Human Papillomavirus Vaccine Recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved on 2008-11-25.