King cobra

| King cobra | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

King cobra

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||||

| Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor, 1836)[2][3][4] | ||||||||||||||||||||

Distribution of the king cobra

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| Synonyms | ||||||||||||||||||||

|

The king cobra (Ophiophagus hannah), also sometimes referred to as Hamadryad, is the world’s largest venomous snake, capable of growing up to 5.5 m (18.04 ft). It is rare, but has a wide distribution. This monotypic genus of the family Elapidae is considered as a species complex, as the species varies in colouration, scalation and body proportion. The king cobra is found in India, Nepal, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Myanmar, China, and most parts of Southeast Asia including Indonesia and the Philippines. The king cobra is listed under: Schedule II of the Indian Wildlife Protection Act 1972; Appendix II of CITES; and in the Vulnerable category by IUCN (2010). This is a very elusive species, rarely seen and which rarely bites humans; when it does, however, the mortality rate is generally low.

Taxonomy and etymology

The king cobra is the sole member of genus Ophiophagus, while most other cobras are members of the genus Naja. They can be distinguished from other cobras by size and hood. King cobras are generally larger than other cobras, and the stripe on the neck is like the symbol "^" instead of a double or single eye shape that may be seen in most of the other Asian cobras. Moreover, the hood of the king cobra is narrower and longer.[5] A foolproof method of identification is if on the head, clearly visible, is the presence of a pair of large scales known as occipitals, at the back of the top of the head. These are behind the usual "nine-plate" arrangement typical of colubrids and elapids, and are unique to the king cobra.

The species was first described by the Danish naturalist Theodore Edward Cantor in 1836. The generic name Ophiophagus comes from comes from the Greek language and literally means "snake eater", ophio = snake and phagus = eater. The specific epithet hannah is derived from the name of tree-dwelling nymphs in Greek mythology (for the arboreal lifestyle).[3]

Description

The king cobra is a distinctive snake. It is the world's longest venomous snake, averaging between 3.1 m (10.17 ft) and 3.8 m (12.47 ft) in length, but the longest recorded specimen was 5.85 m (19.19 ft) in length. However, this is very rare and most specimens don't usually grow longer than 4.3 m (14.11 ft) in length. The London Zoo had one in its collection from Negeri Sembilan (Peninsular Malaysia) that grew to 5.71 m (18.73 ft) in total length, when it had to be put down at the outbreak of World War II in 1939, to avoid it escaping. Tail length accounts for approximately 20% of the total length of the snake. The body scales are smooth and strongly oblique. The adult is brown or olive above with scales dark-edged especially on tail and posterior body with traces of whitish crossbars. The throat is orange-yellow or cream coloured with irregular blackish markings, and the belly greyish-brown. The belly may be uniform in colour or ornamented with bars. In Myanmar, the banded pattern persists in adults.The young, at least up to about 60 cm (23.62 in), is dark-brown or black above with many white or yellow crossbars that are narrow and chevron-shaped with forward-pointing apices. The head is black above with four white cross-bars. The head and body are white below, with the ventrals and subcaudals bordered with black. The dorsal scales are in 15 rows. There are seven upper labial scales, with the third and fourth upper labials in contact with the eye, and the third upper labial touching the posterior nasal. A pair of large and diagnostic occipital shields are found behind the parietals, with the occipital shields in contact with each other at the midline. The underside has 215–264 ventral scales, with the anal shield entire. There are 80–125 subcaudal scales, with the anterior subcaudals single and posterior subcaudals paired. In the field, the king cobra is easily confused with the keeled rat snake (Ptyas carinata), but its larger head, smaller eyes, its pair of large occipital shields, and, when harassed, its habit of rearing up the anterior one-third of the body with neck flattened dorso-ventrally, are unmistakable.[6][7]

Distribution, habitat and status

Geographical distribution

The king cobra is widespread throughout South and Southeast Asia.[8][9] It is recorded from Pakistan, Bhutan, Nepal, India (including the Andaman Islands), Bangladesh, Myanmar, southern China (including Hong Kong and the island province of Hainan), Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand, Peninsular Malaysia, Singapore, Indonesia in the islands of Borneo (Sarawak, Sabah, Brunei, and Kalimantan), Sumatra (including Simeulue, Nias, Banka, Belitung, and Riau Islands), Java, Bali, Sulawesi, and the Philippines (Dinagat, Luzon, Mindanao, Mindoro, Negros, Jolo, Palawan, and Balabac Islands).[7]

Records of the king cobra from Pakistan seem doubtful, and the population in the Western Ghats of India appears to be isolated. Although only Ophiophagus hannah is presently recognised, there is considerable geographic variation among populations and systematic studies have suggested that a complex of several species is involved.[7]

Habitat

The king cobra inhabits a wide range of habitats. It inhabits tropical and subtropical wet forests, lowlands, swamps and marshes, open scrubland, plantations, cultivated areas, rice paddies and often in the vicinity of human habitation. Nevertheless, it requires dense vegetation in which to retreat and hide.[9] It occurs in jungle and primary and secondary forest, woodlands, and open fields. Its preferred habitat is thick primary forests and estuarine mangrove swamps with heavy rainfall[8] and has been reported to occupy humid jungles with thick undergrowth, cool swamps and bamboo clusters.[10] In terms of altitudinal distribution, this species is known to inhabit from 150 m (492.13 ft) to 1530 m (5019.69 ft) in Nepal,[11] from sea level to 1800 m (5905.51 ft) in Sumatra[12] and has been reported up to 2181 m (7155.51 ft) in Mussoori Hills in India.[13]

Conservation status

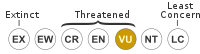

The king cobra has been assessed as Vulnerable under criterion A2cd. This species has a wide distribution range, however, it is not common in any area in which it occurs. A population reduction of 30% over 75 years has been inferred because of the numerous threats against this species, including habitat destruction and harvesting of mature individuals from the wild. Conservation measures are required to reduce the rate of habitat loss within its range and to protect this species from persecution. Research into, and monitoring of the population status of this species is recommended to gain a better understanding of how the population responds to threats and conservation. This species is threatened by destruction of habitat due to mining, logging and agricultural expansion and the harvesting of individuals for skin, food and medicine. Southeast Asia is experiencing one of the highest rates of deforestation in the tropics. It is also used in the domestic and international pet trade, and suffers persecution by humans in parts of its range. Animals are also illegally collected for their venom in parts of its range. It is collected by snake charmers in India. The wild population in China was considered as "very low" in the 1990's, which very likely reflects the trade impact in China for medicinal purposes.[1]

Behaviour and ecology

Behaviour and habits

The king cobra is cannibalistic, terrestrial and hunts at all times of day, although it is rarely seen at night, leading some to wrongly classify it as a diurnal species. Although mainly terrestrial, this agile and fast-moving snake can climb well, and in captivity, is often observed resting on branches and logs above the ground. The young is also said to be semi-arboreal. The king cobra has a fearsome reputation, but in reality this snake is generally not aggressive and will often quickly escape to cover if disturbed. However, it will become aggressive during the mating season and when cornered or provoked. It will raise its forebody high off the ground and spread its narrow hood and make a growling-like noise in defense. There are many smaller venomous snakes within this species range that are responsible for a far greater number of fatal snakebites.[7] King cobras, like other snakes, receive chemical information ("smell") via their forked tongues, which pick up scent particles and transfer them to a special sensory receptor (Jacobson's organ) located in the roof of its mouth.[9] When the scent of a meal is detected, the snake flicks its tongue to gauge the prey's location (the twin forks of the tongue acting in stereo); it also uses its keen eyesight (king cobras are able to detect moving prey almost 100 m (328.08 ft) away), intelligence and sensitivity to earth-borne vibration to track its prey.

Diet

The king cobras diet is mainly composed of other snakes. It prefers non-venomous snakes, however, it will also eat other venomous snakes including kraits and Indian cobras. Cannibalism is not rare. When food is scarce, king cobras will also feed on other small vertebrates such as lizards. Like all snakes, they swallow the prey whole, head first. The top and bottom jaws are attached to each other with stretchy ligaments, which let the snake swallow animals wider that itself. Snakes cannot chew their prey. Food is digested by very strong acids in the snakes stomach. After a large meal the snake may live for many months without another meal due to a very slow metabolic rate.[8]

Reproduction

King cobras can live for up to 20 years and reach sexual maturity when they are around 5-6 years old. They live solitary lives until it is breeding season in January. The females attract the males at the beginning of the breeding season by shedding their skin to release pheromones. If the female attracts more than one male, the males have to fight each other for her attention. Their fighting involves forcing each other to the ground to establish strength and dominance. Once a male wins, he will try to court the female. If she responds, the male will wrap its body around the female to mate, and the pair can stay in this position for a few hours. The females can store sperm in their body for a couple of years and later use it to impregnate themselves. The king cobra is unusual among snakes in that the female king cobra is a very dedicated parent. She makes a nest for her eggs, scraping up leaves and other debris into a mound in which to deposit them, and remains in the nest until the young hatch. A female usually deposits 20 to 40 eggs into the mound, which acts as an incubator. She stays with the eggs and guards the mound tenaciously, rearing up into a threat display if any large animal gets too close, for roughly 60 to 90 days.[14] Inside the mound the eggs are incubated at a steady 28 °C (82 °F). When the eggs start to hatch, instinct causes the female to leave the nest and find prey to eat so she does not eat her young. The baby king cobras, with an average length of 45 cm (17.72 in) to 55 cm (21.65 in), have venom which is as potent as that of the adults. They may be brightly marked but these colours often fade as they mature.[5]

Venom

The venom of the king cobra consists primarily of neurotoxins, but it also contains cardiotoxic and some other compounds.[15] King cobra venom is relatively weak compared to other large venomous snake species such as the black mamba and coastal taipan. Most "true cobras" are also more venomous than the king cobra. Dr. Bryan Grieg Fry of the University of Queensland lists the subcutaneous LD50 at 1.8 mg/kg,[16] while Brown (1973) lists it as 1.7 mg/kg.[17] However, due to its size, the king cobra can produce massive amounts of venom, which makes up for its lesser toxicity. The average venom yield per bite according to both Brown (1973) and Engelmann & Obst (1981) is 421 mg (dry weight).[17][18] Mark O'Shea lists a venom yield range of 200-500 mg per bite.[5] Mortality rates vary sharply depending on many factors. Most bites involve non-fatal amounts.[15][19][20]

Cited references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ophiophagus hannah at The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Ophiophagus hannah (TSN 700646) at Integrated Taxonomic Information System. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Ophiophagus hannah (CANTOR, 1836) at The Reptile Database. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- ↑ Ophiophagus hannah at National Center for Biotechnology Information. Accessed 23 May 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 O'Shea, Mark. (2005). Venomous Snakes of the World. UK: New Holland Publishers. ISBN 0-691-12436-1

- ↑ Leviton, Alan E.; Guinevere O.U. Wogan; Michelle S. Koo; George R. Zug; Rhonda S. Lucas and Jens V. (2003). The Dangerously Venomous Snakes of Myanmar. Illustrated Checklist with Keys. Proc. Cal. Acad. Sci. 54 (24): 407–462

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 Lim, Kelvin. Leong, Tzi Ming. Lim, Francis. (2011). The King Cobra, Ophiophagus hannah (Cantor) in Singapore (Reptilia: Squamata: Elapidae). Nature in Singapore (National University of Singapore). 4: 143–156.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 Whitaker, Romulus; Captain, Ashok (2004). Snakes of India: The Field Guide. Chennai, India: Draco Books. ISBN 81-901873-0-9.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Mehrtens, John. (1987). Living Snakes of the World. New York: Sterling. ISBN 0-8069-6461-8.

- ↑ Bashir, T. Poudyal, K. Bhattacharya, T. Sathyakumar, S. Subba, JB. (June 2010). Sighting of King Cobra Ophiophagus hannah in Sikkim, India: a new altitude record for the northeast. Journal of Threatened Taxa. 2 (6): 990-991.

- ↑ Selich, H. & W. Kästle (eds) (2002). Amphibians and Reptiles of Nepal. Gantner, A.R.G., V.G. Verlag & Ruggell (distributed by Koeltz, Koenigstein, Germany), 1201pp, 127pls. (includ- ing 374 col. figs).

- ↑ David, P. & G. Vogel (1996). The Snakes of Sumatra: An Anno- tated Checklist and Key with Natural History Notes. Edition Chimaira, Frankfurt-am-Main, Germany, 260pp.

- ↑ Waltner, R.G. (1975). Geographical and altitudinal distribution of Amphibians and reptiles in the Himalayas - Part IV. Cheetal 16: 12-17.

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007). Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-33922-8.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Capula, Massimo; Behler ((1989)). Simon & Schuster's Guide to Reptiles and Amphibians of the World. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-69098-1.

- ↑ Fry, Bryan Grieg. LD50. Australian Venom Research Unit. University of Queensland. Retrieved on 7 May 2012.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Brown Ph.D, John H. (1973). Toxicology and Pharmacology of Venoms from Poisonous Snakes. Springfield, IL USA: Charles C. Thomas Publishers, 81–82. ISBN 0-398-02808-7.

- ↑ Engelmann, Wolf-Eberhard (1981). Snakes: Biology, Behavior, and Relationship to Man. Leipzig; English version NY, USA: Leipzig Publishing; English version published by Exeter Books (1982). pp. 222. ISBN 0-89673-110-3.

- ↑ Dangerous Snakes at Sean Thomas. Accessed 25 May 2012.

- ↑ Mathew, J. L., and T. Gera. (2000). Ophitoxaemia (venomous snake bite). Priory.com. Accessed 25 May 2012.