Plant breeding

- See Agriculture for related topics and context

- See Crop origins and evolution for the beginnings of plant breeding

Plant breeding is the purposeful manipulation of plant species in order to create desired genotypes and phenotypes for specific purposes, such as food production, forestry, and horticulture.

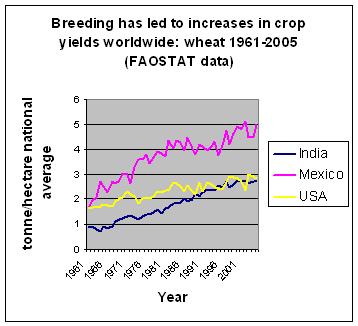

Plant breeding has been practiced since the beginning of human civilization, but practical successes in plant breeding since 1900 have been greatly stimulated by concepts and techniques developed in the science of genetics. This scientific plant breeding has contributed about 50% of the improvement in crop yield seen in the major cereal crops since 1930 [1].

Plant breeding is an artificial version of natural evolution, involving artificial selection of desired plant characteristics and artificial generation of genetic variation.

Plant breeding complements other farming innovations (such as introduction of new crops, grafting, changed crop rotations and tillage practices, irrigation, and integrated pest management) for improving crop productivitry and land stewardship, and during the period from 1930 onwards in concert with these other innovations has led to spectacular increases in crop yields especially with cereal grains.

Plants breeding is now practiced worldwide by both government institutions and commercial enterprises. International development agencies believe that breeding new crops is important for ensuring food security and developing practices of sustainable agriculture through the development of crops suitable for minimizing agriculture's impact on the environment [2] [3].

Domestication

- See main article Crop origins and evolution

Domestication of plants is an artificial selection process conducted by humans to produce plants that have fewer undesirable traits of wild plants, and which renders them dependent on artificial (usually enhanced) environments for their continued existence. The practice is estimated to date back 9,000-11,000 years. Many crops in present day cultivation are the result of domestication in ancient times, about 5,000 years ago in the Old World and 3,000 years ago in the New World. In the Neolithic period, domestication took a minimum of 1,000 years and a maximum of 7,000 years. Today, all of our principal food crops come from domesticated varieties.

A cultivated crop species that has evolved from wild populations due to selective pressures from traditional farmers is called a landrace. Landraces, which can be the result of natural forces or domestication, are plants (or animals) that are ideally suited to a particular region or environment. An example are the landraces of rice, Oryza sativa subspecies indica, which was developed in South Asia, and Oryza sativa subspecies japonica, which was developed in China.

Genetics and crop breeding intertwined

Plant breeders created the earliest recorded artificial hybrids between different species (such as the feed cereal Triticale) in the late 19th century, and discoveries in fundamental genetics have been intertwined with crop breeding since then. In 1903 W. L. Johannsen defined the heritable component of biological variabiliity in experiments with a self-pollinated bean. US plant breeder G. H. Scull discovered substantial crop yield improvements in interspecies hybrids of maize (now called hybrid vigor or heterosis) in 1908 with dramatic consequences for development of a successful commercial corn-seed breeding industry, first in the US and later elsewhere. Plant geneticists subsequently came to realize how hybridization can allow fuller exploitation of genetic diversity available in a plant population, and developed widely used interspecies hybrids for pearl millet, sorhum, rice and rapeseed (canola) crops.

Barbara McClintock developed fundamental concepts about chromosome behavior and cytogenetics with maize in the 1930s. Chromosome and genome relationships both within and between crops species have been the conceptual keystones to much successful crop breeding [4]. It is now realized that most crops have undergone duplication the minimal diploid set of chromosome at some stage, either as ancient duplications (as in the case of maize), or by hybridization between different species (as in allopolyploids such as wheat)

Protection of major crops against disease has rested on alien gene transfer using chromosomal engineering. This technique relies on manipulation of chromosome pairing at meiosis. In 1956 chromosomal engineering enabled Ernest Sears to translocate a segment of goatgrass (Agilops umbellulata Zhuk) chomosome that conferred resistance to leaf rust onto wheat chromosome 6B [5], and this achievement was followed by numerous successes in transfers of alien genes to crop plants by chromosome manipulation (the so-called wide-crosses) [6] (see also wheat.)

Chromosomal engineering is facilitated by using X-ray radiation to promote chromosome breakage, plant tissue culture, and mutants such as Ph-1 of wheat that relax normal strict pairing of homologous chromosomes in meiosis [7] [8] [9]. It can be valuable to artificially promote doubling of chromosome number using colchicine in inter-species and inter-generic cross hybrid lines as a step to enable transfer of alien chromosome segments into crop germplasm [10].

The expansion of biotechnology after 1980 led to many advances in genetics which are accellerating the usually slow process of plant breeding and leading to important theoretical discoveries that improve plant breeding, such as molecular markers, plant genomics, RNA interference, and numerous gene characterizations such as the genes affecting abiotic stress responses and pest and pathogen tolerance.

Strategies and approaches for scientific plant breeding

The starting points for plant breeding is identification of novel useful traits in populations of parental organisms. The use of chemically or radiation induced mutation can also exploited to increase the range of useful genetic variability, and plant breeding exploits genetic recombination to generate novel combinations of traits. The end-result of lengthy selective breeding programs using these methods is "elite" varieties of high performing germplasm for major crops that are used widely in broad-acre farming.

Plant breeding strategies used by the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center (CIMMYT) encapulate the way in which modern plant breeding should be pursued.

CIMMYT wheat breeding strategies aim to achieve an optimal combination of the best genotypes (G), in the right environments (E), under appropriate crop management (M), and appropriate to the needs of the people (P) who must implement and manage them. This yields the CIMMYT “sustainability equation” of GxExMxP. [11]

Useful traits

Techniques for increasing the available heritable variation in the initial population include introduction of new germplasm from distant geographical regions or from seed-bank collections, cross-pollination, either within the species, or between related species and genera - including wide-crosses using wild relatives of domesticated plants to introduce pest resistant traits needed in domesticated varieties, and creation of mutations by irradiation or chemical treatment.

Hope

RESISTANCE TO STEM RUST was transferred from Triticum turgidum L. ssp. dicoccum Schrank ex Schübler (cv Yaroslav) into hexaploid wheat by McFadden (1930) producing the variety Hope. Hare and McIntosh (1979) determined that stem rust resistance in Hope was largely controlled by a single gene located on the short arm of chromosome 3B. The resistance gene was named Sr2 and assumed to have come from T. turgidum, though the original tetraploid accession was lost and could not be confirmed to carry the gene. The cultivar Hope was used in Mexico during the 1940s as the donor for developing the stem rust resistant wheat cultivar Yaqui 48 (Borlaug, 1968). Since then, the Sr2 gene has been employed widely by CIMMYT's global wheat improvement program in Mexico, and germplasm exchange from CIMMYT has distributed it to many wheat production regions of the world. The gene has provided durable, broad-spectrum rust resistance effective against all isolates of P. graminis worldwide for more than 50 yr. On the basis of its past performance, Sr2 has been described as one of the most important disease resistance genes deployed in modern plant breeding (McIntosh et al., 1995) [12].

The dwarfing trait confers a change in plant stature that provides resistance to lodging and nitrogen fertiliser responsiveness, and exploitation of this trait in wheat and rice was responsible for many of the successes of the Green Revolution, which revolutionized wheat and rice production in Asia, averting mass-famines.

In 1963, scientists discovered the gene called opaque-2, which improves the nutritional quality of the maize by increasing its lysine and tryptophan content. These two amino acids are important in determining the nutritional quality of protein. At first farmers initially showed little interest in opaque-2 maize because of its low yields, chalky-looking grain, and othwer defects. But thirty years of breeding effort organised by CIMMYT finally led to releases of Quality Protein Maize varieties - QPM - to farmers,.which are now widely used in regions where maize is a staple food [13] [14].

Fusarium head blight is a devastating disease of durum wheat, and a resistant gene to fungus that causes head blight has been transferred into durum wheat germplasm from wheatgrass Lophopyrum elongatum by chomosome engineering [15] .

Hybrids and hybrid vigor

Male cytoplasmic sterility and other approaches is exploited to create artificial hybrids, and the greater vigor from hybrid vigor (heterosis) is taken advantage of in several important crops (e.g. maize, rice, canola), whether it is a natural hybrid system of a synthetic one.

Hybrid vigor is related partly to presence of heterozygosity, that is two alternative version of the same gene. Another another factor having a similar effect is polyploidy, or presence of multiple sets of chromosomes. All crop genomes are polyploid, bread wheat for instance is hexaploid, and maize an ancient tetraploid. These genetic features of crop plants add extra subtlety to crop breeding and ensure that germplasm collections have great practical value [16] [17] .

Recombination

In addition to taking advantage of natural gene flow and horizontal gene transfer events to allow new traits to be added to existing crops, it also uses artificial means for gene transfer such as embryo rescue and biolistics to overcome natural barriers to gene flow between different gene-pools.

Genetic engineering to generate transgenic plants, and gene silencing (called RNA interference or cisgenics) are other methods now used to obtain useful variants.

Barriers to gene-flow between different plant species are overcome in a number of ways. Colchicine treatment to create artificial polyploids can overcome some of the sterility problems from inter-species cross pollination. Cochicine interferes with early steps in meiosis and results in formation of diploid rather than haploid gametes. Crosses made using protoplast fusion (somatic hybridization) can also be used, and embryo rescue methods can also circumvent gene-flow barriers.

Improved selection of better varieties

Many artificial selection methods have been developed to allow crop improvement to be sucessful. This include molecular marker assisted breeding[18] [19], and use of statistical principles to design field tests of crop candidate performance with sufficient power to detect improvement.

Genome science (chromosome sequence decoding and computer assisted dissection of gene functions and structure) is also being bought into play to assist plant breeders identify traits and select improved progeny. One approach is to compare gene arrangement in different species (comparative genomics) to take advantage of the greater ease of gene sequencing and faster progress with smaller more compact genomes such as those of Arabidopsis thaliana, or of rice, to provide clues for gene function and location in crop species with larger genomes.

Identification of the particular gene and DNA sequences determining a phenotype of relevance to agriculture (such as restistance to rust fungal pathogens) opens up numerous ways of creating new useful genetic variation by direct manipulation of DNA, and for devising practicable tests for tracking traits such as water use efficiency [20] and pathogen resistance which are difficult to identify in breeding experiments, thus speeding up plant breeding in the greenhouse and field trial stages.

For instance, microsatellite molecular markers have been developed that are practically useful for detecting the important Stem rust resistance trait (Sr2, present in cultivar Hope) in wheat. They rely on the PCR technique for detecting this gene that is difficult to score using conventional methods based on plant phenotype [21].

Germplasm collections

It was in the 1930s that Russian scientist Nikolai Vavilov first called attention to the value of wild crop relatives as a source of genes for improving agriculture, and in travels over five continents amassed the largest collection of (at that time) of species and strains of cultivated plants in the world. [22] [23]

Vavilov's intent was to promote crop improvement but since his time other considerations have added to expansion of seed-banks. One major concern is the limited genetic diversity of crop plants, and the vulnrabilities to crop diseases that it introduces into the food supply. This genetic vulnrability was highlighted in 1970 by a severe outbreak of Southern corn leaf blight in the United States.

The FAO estimate that globally, distinct seed samples in plant seed collections total over 6 million samples, held in in 1300 genebanks worldwide (B. Koo and others in Saving Seeds 2004, citing FAO 1998). About 10 percent of these are held by the substantial international network of crop germplasm collections managed by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR).

CGIAR is a strategic alliance of countries, international and regional organizations, and private foundations supporting 15 international agricultural centers that was created in 1971. CGIAR genbanks include

- Centro Internacional de Mejoramiento de Maiz y Trigo (maize and wheat; CIMMYT) Genebank, (Mexico.

- International Center for Agricultural Research in the Dry Areas (ICARDA) Genebank, (Syria).

- International Crops Research Institute for the Semi-Arid Tropics (ICRISAT) Genebank, (India).

- International Rice Research Institute IRRI Genebank, (Philipines).

- Internacional de Agricultura Tropical (International Center for Tropical Agriculture; CIAT) Genebank, (Columbia)

Recent achievements coming from this germplasm resource and the associated CGIAR network of scientists include:

- Quality Protein Maize (QPM) varieties have been released in 25 countries, and are grown on more than 600,000 hectares

- New Rices for Africa (NERICAs) from Africa Rice Center (WARDA) that are transforming agriculture in the West Africa region. In 2003 it is estimated that NERICAs were planted on 23,000 hectares, and their use is spreading across Africa, for instance to Uganda and Guinea.

- Release across Latin America of many new bean varieties and improved forages that are grown on over 100 million hectares in that region.

Classical plant breeding

Genetic modification and its post-1975 consequences for plant breeding

- See main article on Biotechnology and Plant breeding .

- See also Transgenic plants.

- See also Horizontal gene transfer in plants.

Twenty first century plant breeding

- See main article on Biotechnology and Plant breeding.

- See also Cisgenic plants.

Issues and concerns

Modern plant breeding, whether classical or through genetic engineering, comes with issues of concern, particularly with regard to food crops.

Surveys of changes in American foods 1950-1999 have suggested there may be decreases in nutitional quality of many garden crops over this time period, possibly because of breeding for higher yield [24]

Such problems are not new though. At the begining of agriculture, a gene was lost from wheat that mobilizes nutrients from leaves, causing better grain yields at the expense of protein content and nutritional value [25] [26]. It has long been known that among the many varieties of wheat used in modern times, there is an inverse relationship between yield and protein content.[27]. There is also increasing recent emphasis on breeding crops for nutritional improvement [28] [29].

The debate surrounding plant breeding genetic modification of plants is huge, encompassing the ecological impact of genetically modified plants and the safety of genetically modified food. It extends also to the issue of Food security because of the strong link between increases in crop output and matching of food supply to growing food demand caused by population growth and economic growth. Agencies such as the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) have highlighted the mis-match between amount of agricultural R&D and food security in the developing world [30].

Plant breeders' rights is also a major and controversial issue. Efforts to strengthen breeders' rights, for example, by lengthening periods of variety protection, are ongoing. Today, production of new varieties is dominated by commercial plant breeders, who seek to protect their work and collect royalties through national and international agreements based in intellectual property rights.

The range of related issues is complex. In the simplest terms, critics of crop-breeding argue that, through a combination of technical and economic pressures, commercial breeders are reducing biodiversity and significantly constraining individuals (such as farmers) from developing and trading seed on a regional level.

But seed breeding is a specialised economic activity that most farmers do not have the time to pursue, and better seed provides a simple means of technology transfer that provides an economic benefit to the farmer. Expansion of a commercialized seed industry is historically associated with substantial economic gains in that sector as illustrated by hybrid maize in the USA, and more recently, the Indian cotton seed industry [31] [32] [33]. Critics of excessive precautionary regulation argue that costly regulatory burdens and delayes imposed on new seed-breeding technologies restrict investment in much modern agricultural technology to organisations having substantial financial assets, which limits the effectiveness of public research efforts in developing countries.

References

Citations

- ↑ Day-Rubenstein, Kelly and Heisey, Paul (2006) Chapter 3.1 Crop Genetic Resources in Wiebe, Keith and Gollehon, Noel Editors, Agricultural Resources and Environmental Indicators, 2006 Edition Economic Information Bulletin No. (EIB-16) , July 2006

- ↑ Ngambeki, D.S. (2005) Science and technology platform for African Development: towards a green revolution in Africa, The New Partnership for Africa's Development

- ↑ Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research. 2002. Agriculture and the environment, partnership for a sustainable future

- ↑ Jauhar, Prem P. (2006) Modern biotechnology as an integral supplement to conventional plant breeding: the prospects and challenges. Crop Science 46.5 (Sept-Oct 2006): p1841

- ↑ Sears, E.R. 1956. The transfer of leaf-rust resistance from Aegilops umbellulata to wheat. Brookhaven Symp. Biol. 9:1-22.

- ↑ Sharma, H.C.and Gill, B.S.(1983) Current status of wide hybridization in wheat. Euphytica 32 pages 17-31

- ↑ Jauhar, Prem P. (2006) Modern biotechnology as an integral supplement to conventional plant breeding: the prospects and challenges. Crop Science 46.5 (Sept-Oct 2006): p1841.

- ↑ Chapman V, Riley R. (1970) Homoeologous meiotic chromosome pairing in Triticum aestivum in which chromosome 5B is replaced by an alien homoeologue. Nature. 1970 Apr 25;226(5243):376-7.

- ↑ Riley R, Chapman V, Kimber G.(1959) Genetic control of chromosome pairing in intergeneric hybrids with wheat. Nature. 1959 May 2;183(4670):1244-6.

- ↑ Jiang, Jiming, Friebe, Bernd, & Gill, Bikram S. (1994) Recent advances in alien gene transfer in wheat. Euphytica 73 : pages 199 - 212.

- ↑ Reeves, T.G., S. Rajaram, M. van Ginkel, R. Trethowan, H-J. Braun, and K. Cassaday. (1999). New Wheats for a Secure, Sustainable Future. Mexico, D.F.: CIMMYT.

- ↑ W., Sharp, P. J., and Lagudah, E. S. (2003) Identification and Validation of Markers Linked to Broad-Spectrum Stem Rust Resistance Gene Sr2 in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Crop Science 43, pages 333-336

- ↑ http://www.cimmyt.org/english/wps/news/2006/aug/qpm-embu.htm The maize with the beans inside: QPM gathers a following in Kenya

- ↑ http://www.cimmyt.cgiar.org/research/maize/world_food_prize_qpm/qpm_wfp.htm Scientists Receive World Food Prize for Decades-Long Scientific Quest To Produce "Quality Protein Maize" for Developing Countries

- ↑ Jauhar, P.P., and T.S. Peterson. 2000. Toward transferring scab resistance from a diploid wild grass, Lophopyrum elongatum, into durum wheat. p. 201-204. In Proc. of the 2000 National Fusarium Head Blight Forum, Cincinnati. 10-12 Dec. 2000.

- ↑ J. A. Udall and J. F. Wendel (2006) Polyploidy and Crop Improvement. Crop Sci. 46, S-3-S-14

- ↑ Wade Odland, Andrew Baumgarten and Ronald Phillips (2006) Ancestral Rice Blocks Define Multiple Related Regions in the Maize Genome Crop Sci 46:41-48

- ↑ Coordinated Agricultural project , UC Davis.

- ↑ Bilyeu, Kristin , Palavalli, Lavanya , Sleper, David A. and Beuselinck, Paul (2006) Molecular Genetic Resources for Development of 1% Linolenic Acid Soybeans. Crop Sci 46:1913-1918 (2006) Published online 25 July 2006 DOI: 10.2135/cropsci2005.11-0426

- ↑ CSIRO Media Release - Ref 2004/33 - Mar 04 , 2004 Huge potential for water-efficient wheat (Delta carbon technology).

- ↑ W., Sharp, P. J., and Lagudah, E. S. (2003) Identification and Validation of Markers Linked to Broad-Spectrum Stem Rust Resistance Gene Sr2 in Wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) Crop Science 43, pages 333-336

- ↑ [Tanksley SD, McCouch SR.(1997). Seed banks and molecular maps: unlocking genetic potential from the wild. Science. 1997 Aug 22;277(5329):1063-6. citing N. I. Vavilov, in The New Systematics, J. Huxley, Ed. (Clarendon, Oxford, 1940), pp. 549–566.]

- ↑ B Koo, International Food Policy Research Institute, (IFPRI), Washington D C, USA; P G Pardey, University of Minnesota, USA; B D Wright, University of California, Berkeley, USA, and others. (2004). Saving Seeds: The Economics of Conserving Crop Genetic Resources Ex Situ in the Future Harvest Centres of CGIAR, page 1 citing Resnick S and Vavilov Y (1997) The Russian Scientist Nicolay Vavilov. Preface to the English translation of Five Continents by N. I Vavilov, International Plant Genetic Resources Institute, Rome.

- ↑ Davis, D.R., Epp, M.D., and Riordan, H.D. (2004). Changes in USDA Food Composition Data for 43 Garden Crops 1950 to 1999. Journal of the American College of Nutrition 23(6):669-682

- ↑ Wheat gene may boost foods' nutrient content

- ↑ Uauy C, Assaf Distelfeld, A, Fahima, T, AnnBlechl, A, Dubcovsky, J (2006) A NAC Gene Regulating Senescence Improves Grain Protein, Zinc, and Iron Content in Wheat Science 24 November 2006: Vol. 314. no. 5803, pp. 1298 - 1301 DOI: 10.1126/science.1133649

- ↑ SIMMONDS NW (1995) THE RELATION BETWEEN YIELD AND PROTEIN IN CEREAL GRAIN JOURNAL OF THE SCIENCE OF FOOD AND AGRICULTURE 67 (3): 309-315 MAR 1995

- ↑ Philip G. Pardey, Julian M. Alston, and Roley R. Piggott, eds. (2006) Agricultural R&D in the Developing World Too Little, Too Late/ DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2499/089629756XAGRD

- ↑ HarvestPlus, an international, interdisciplinary, research program that seeks to reduce micronutrient malnutrition by harnessing the powers of agriculture and nutrition research to breed nutrient dense staple foods.

- ↑ Philip G. Pardey, Julian M. Alston, and Roley R. Piggott, eds. (2006) Agricultural R&D in the Developing World Too Little, Too Late/ DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.2499/089629756XAGRD

- ↑ C Kameswara Rao 2006) PERFORMANCE OF Bt COTTON IN INDIA: THE 2005-06 SEASON, Foundation for Biotechnology Awareness and Education, Bangalore, India

- ↑ Milind Murugkar, Bharat Ramaswami, Mahesh Shelar, January 2006, Liberalization, Biotechnology and the Private Seed Sector: The Case of India’s Cotton Seed Market Discussion Paper 06-05, Indian Statistical Institute, Delhi

- ↑ Duvick DN. (2001) Biotechnology in the 1930s: the development of hybrid maize. Nat Rev Genet. 2001 Jan;2(1):69-74.

Further reading

- Borojevic, S. (1990) Principles and Methods of Plant Breeding. Elsevier, Amsterdam. ISBN 0-444-98832-7

- Chrispeels, M.J.,and Sadava, D.E. Editors.(2003) Plants, Genes, and Crop Biotechnology. 2nd Edition. Jones and Bartlett/American Society of Plant Biologists ISBN 0-7637-1586-7

- Duvick DN. (2001) Biotechnology in the 1930s: the development of hybrid maize. Nat Rev Genet. 2001 Jan;2(1):69-74.

- Fedoroff, N. V. and Brown, N. M. (2004) Mendel in the Kitchen: A Scientist's View of Genetically Modified Food. National Academy Press. ISBN 0-3090-9205-1

- Gepts, P. (2002) A Comparison between Crop Domestication, Classical Plant Breeding, and Genetic Engineering. Crop Science 42:1780–1790

- Origins of Agriculture and Crop Domestication - The Harlan Symposium

- Gewin V (2003) Genetically Modified Corn— Environmental Benefits and Risks. PLoS Biol 1(1): e8 DOI: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000008

- Hoisington, D. and others (1999) Plant genetic resources: What can they contribute toward increased crop productivity? Proc. Natl. Acad Sci USA. Vol. 96, Issue 11, 5937-5943, May 25, 1999. (This paper was presented at the National Academy of Sciences colloquium "Plants and Population: Is There Time?" held December 5-6, 1998, at the Arnold and Mabel Beckman Center in Irvine, CA).

- Jauhar, Prem P. (2006) Modern biotechnology as an integral supplement to conventional plant breeding: the prospects and challenges. Crop Science 46.5 (Sept-Oct 2006): p1841(19).

- McCouch, S. (2004) Diversifying Selection in Plant Breeding. PLoS Biol 2(10): e347.

- Reeves, T.G., S. Rajaram, M. van Ginkel, R. Trethowan, H-J. Braun, and K. Cassaday. (1999). New Wheats for a Secure, Sustainable Future. Mexico, D.F.: CIMMYT.

- Pfeiffer, T. W. (2003) From classical plant breeding to modern crop improvement. Chapter 14 In Chrispeels, M.J.,and Sadava, D.E. 2003 Editors. Plants, Genes, and Crop Biotechnology. 2nd Edition. Jones and Bartlett/American Society of Plant Biologists ISBN 0-7637-1586-7