John W. Campbell, Jr.

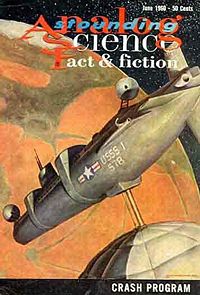

John Wood Campbell, Jr., generally known as John W. Campbell, (June 8, 1910 – July 11, 1971) was the influential editor of Astounding Science Fiction from 1937 until his death in 1971. After first establishing himself as a well-known science-fiction author, he then devoted himself exclusively to editing. As the editor of the most important magazine in the field, he launched the careers of most of the key figures in what is still generally known as the Golden Age of Science Fiction, including Robert A. Heinlein, Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, A.E. van Vogt, and Arthur C. Clarke. Although Campbell had many eccentricities, some of which, such as a belief in psionics, later found their way increasingly into his publications in the 1950s and '60s, he remains, almost without question, the single most important figure in the development of modern science fiction, with the possible exception of his protégé Robert Heinlein.

Editorship of Astounding and Unknown; the Golden Age

Campbell was regarded by many of the Astounding stable of writers as an important and encouraging influence on their work, and there are many stories in the reminiscences of writers such as Isaac Asimov and Lester del Rey of their interactions with him. Generally, he is widely considered to be the single most important and influential editor in the history of science fiction. As the Science Fiction Encyclopedia, edited by Peter Nicholls, wrote about Campbell: "More than any other individual, he helped to shape modern sf." This influence is generally considered to be during the period between 1938 and about 1950. After that, new magazines such as Galaxy and the Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, building upon the foundation Astounding had laid during the so-called Golden Age of Science Fiction, moved in different directions and developed talented new writers who were not directly influenced by him.

Asimov says of his unmatched influence on the field: "By his own example and by his instruction and by his undeviating and persisting insistence, he forced first Astounding and then all science fiction into his mold. He abandoned the earlier orientation of the field. He demolished the stock characters who had filled it; eradicated the penny-dreadful plots; extirpated the Sunday-supplement science. In a phrase, he blotted out the purple of pulp. Instead, he demanded that science-fiction writers understand science and understand people, a hard requirement that many of the established writers of the 1930s could not meet. Campbell did not compromise because of that: those who could not meet his requirements could not sell to him, and the carnage was as great as it had been in Hollywood a decade before, when silent movies had given way to the talkies." [1]

The most famous example of the type of speculative but plausible science fiction that Campbell demanded from his writers is Deadfall, a short story by Cleve Cartmill that appeared during the wartime year of 1944, a year before the detonation of the first atomic bomb. As Ben Bova, Campbell's successor as editor at Analog, writes, it "described the basic facts of how to build an atomic bomb. Cartmill and... Campbell worked together on the story, drawing their scientific information from papers published in the technical journals before the war. To them, the mechanics of constructing a uranium-fission bomb seemed perfectly obvious." The FBI, however, descended on Campbell's office after the story appeared in print and demanded that the issue be removed from the newsstands. Campbell convinced them that by removing the magazine "the FBI would be advertising to everyone that such a project existed and was aimed at developing nuclear weapons" and the demand was dropped. [2]

Campbell revealed a sly sense of humor in the November 1949 issue. He had always encouraged literary criticism by Astounding's readership, and in the November 1948 issue he published a letter to the editor by a reader named Richard A. Hoen that contained a detailed ranking of the contents of an issue one year in the future. Campbell went along with the joke and contracted stories from most of the authors mentioned in the letter that would follow the fan's imaginary story titles. Ironically, when the issue actually appeared, Hoen had forgotten his original letter, and was supposedly "amazed at how many of my favorite authors appeared in one issue". Template:Fact One of the best-known stories from that issue is "Gulf", by Robert A. Heinlein. Other stories and articles were written by a number of the most famous authors of the time: Isaac Asimov, Theodore Sturgeon, Lester del Rey, A. E. van Vogt, L. Sprague de Camp, and the astronomer R. S. Richardson. [3]

In 1996, Campbell was inducted into the Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame, in the first year of its existence.[4]

Editorials and opinions

Campbell was well known for the opinionated editorials in each issue of the magazine, wherein he would sometimes put forth quite preposterous hypotheses, perhaps intended to generate story ideas. An anthology of these editorials was published in 1966. He also suggested story ideas to writers (including, famously, "Write me a creature that thinks as well as a man, or better than a man, but not like a man"), and sometimes asked for stories to match cover paintings he had already bought.

Isaac Asimov once asked Campbell why he had stopped writing fiction after he became the editor of Astounding. Campbell explained, "Isaac, when I write, I write only my own stories. As editor, I write the stories that a hundred people write." [5]

Science-fiction writer Joe Green writes that Campbell "enjoyed taking the 'devil's advocate' position in almost any area, willing to defend even viewpoints with which he disagreed if that led to a livelier debate." As an example, he says that during a conversation with him Campbell "pointed out that the much-maligned 'peculiar institution' of slavery in the American South had in fact provided the blacks brought there with a higher standard of living than they had in Africa." Green goes on to say that he was "very much afraid that in fact he was sincere. I suspected, from comments by Asimov, among others — and some Analog editorials I had read — that John held some racist views, at least in regard to blacks." Finally, however, Green agreed with Campbell that "rapidly increasing mechanization after 1850 would have soon rendered slavery obsolete anyhow. It would have been better for the USA to endure it a few more years than suffer the truly horrendous costs of the Civil War." [6]

In the 1950s, Campbell developed strong interests in alternative theories that began to isolate him from some of his own mainstream writers such as Asimov. He wrote favorably, for instance, about such things as the "Dean drive," a device that supposedly produced thrust in violation of Newton's third law, and the "Hieronymus machine," which could supposedly amplify psi powers. He published many stories about telepathy and other psionic abilities. In 1949 Campbell also became interested in Dianetics. He was initially a strong supporter, writing of Hubbard's initial article in Astounding that "It is, I assure you in full and absolute sincerity, one of the most important articles ever published."[7] He also claimed to have successfully used dianetic techniques himself: "The memory stimulation technique is so powerful that, within thirty minutes of entering therapy, most people will recall in full detail their own birth. I have observed it in action, and used the techniques myself."[7] In addition to publishing L. Ron Hubbard's first articles on the subject, Campbell continued to write editorials in support of Dianetics for a time.

Writing about the Campbell of this period, the noted science-fiction writer and critic Damon Knight commented in his book In Search of Wonder: "In the pantheon of magazine science fiction there is no more complex and puzzling figure than that of John Campbell, and certainly none odder." Knight also wrote a four-stanza ditty about some of Campbell's new interests. The first stanza reads:

- Oh, the Dean Machine, the Dean Machine,

- You put it right in a submarine,

- And it flies so high that it can't be seen --

- The wonderful, wonderful Dean Machine!

And Isaac Asimov writes: "A number of writers wrote pseudoscientific stuff to ensure sales to Campbell, but the best writers retreated, I among them." [8]

Asimov was not alone in his opinion. In 1957, the novelist and critic James Blish could write: "From the professional writer's point of view, the primary interest in Astounding Science Fiction continues to center on the editor's preoccupation with extrasensory powers and perceptions ("psi") as a springboard for stories.... 113 pages of the total editorial content of the January and February 1957 issues of this magazine are devoted to psi, and 172 to non-psi material.... [By including the first part of a serial that later becomes a novel about psi] the total for these first two issues of 1957 is 145 pages of psi text, and 140 pages of non-psi." [9]

Asimov also says that "Campbell championed far-out ideas.... He pained very many of the men he had trained (including me) in doing so, but felt it was his duty to stir up the minds of his readers and force curiosity right out to the border lines. He began a series of editorials... in which he championed a social point of view that could sometimes be described as far right. (He expressed sympathy for George Wallace in the 1968 national election, for instance.) There was bitter opposition to this from many (including me — I could hardly ever read a Campbell editorial and keep my temper). [10]

In the eyes of others

Asimov says in his autobiography that Campbell was "talkative, opinionated, quicksilver-minded, overbearing. Talking to him meant listening to a monologue.... He was a tall, large man with light hair, a beaky nose, a wide face with thin lips, and with a cigarette in a holder forever clamped between his teeth."[11] "Six-foot-one, with hawklike features, he presented a formidable appearance," says Sam Moskowitz, a well-known fan and historian of the field.[12] Damon Knight's opinion of Campbell was similar to Asimov's: "No doubt I could have got myself invited to lunch long before, but Campbell's lecture-room manner was so unpleasant to me that I was unwilling to face it. Campbell talked a good deal more than he listened, and he liked to say outrageous things."[13] The notable British novelist and critic Kingsley Amis, in his seminal 1960 book about science fiction, New Maps of Hell, dismisses Campbell brusquely: "I might just add as a sociological note that the editor of Astounding, himself a deviant figure of marked ferocity, seems to think he has invented a psi machine." [14]

The noted science-fiction writer Alfred Bester, an editor of Holiday Magazine and a sophisticated Manhattanite, recounts at some length his "one demented meeting" with Campbell, a man he imagined from afar to be "a combination of Bertrand Russell and Ernest Rutherford," across the river in Newark.[15] The first thing Campbell said to him was that Freud was dead, destroyed by the new discovery of Dianetics, which, he predicted, would win L. Ron Hubbard the Nobel Peace Prize. Over a sandwich in a dingy New Jersey lunchroom Campbell ordered the bemused Bester to "think back. Clear yourself. Remember! You can remember when your mother tried to abort you with a button hook. You've never stopped hating her for it." Shaking, Bester eventually made his escape and, he says, "returned to civilization where I had three double gibsons." He adds: "It reinforced my private opinion that a majority of the science-fiction crowd, despite their brilliance, were missing their marbles."

Asimov's final word on Campbell was that "in the last twenty years of his life, he was only a diminishing shadow of what he had once been."[16] Even Robert A. Heinlein, perhaps Campbell's most important discovery and, Virginia Heinlein tells us, by 1940 a "fast friend", [17] eventually tired of Campbell. "When Podkayne [Podkayne of Mars] was offered to him, he wrote Robert, asking what he knew about raising young girls in a few thousand carefully chosen words. The friendship dwindled, and was eventually completely gone." [18] In 1963 Heinlein wrote his agent to say that a rejection from another magazine was "pleasanter than offering copy to John Campbell, having it bounced (he bounced both of my last two Hugo Award winners) — and then have to wade through ten pages of his arrogant insults, explaining to me why my story is no good." [19]

References

- ↑ Introduction: The Father of Science Fiction, by Isaac Asimov, in Astounding edited by Harry Harrison, pages ix-x

- ↑ Through Eyes of Wonder, by Ben Bova, pages 66-67

- ↑ A Requiem for Astounding, by Alva Rogers, pages 176-180

- ↑ Science Fiction and Fantasy Hall of Fame. Retrieved on 21 June, 2006.

- ↑ The quote is from Asimov's introduction to ASTOUNDING: John W. Campbell Memorial Anthology (1973)

- ↑ Our Five Days with John W. Campbell, by Joe Green, The Bulletin of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Fall 2006, No. 171, page 15

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 (April 1950) "Astounding Science Fiction": 132.

- ↑ I. Asimov, Isaac Asimov, page 74

- ↑ James Blish, The Issues at Hand, pages 86-87.

- ↑ Introduction: The Father of Science Fiction, by Isaac Asimov, in Astounding edited by Harry Harrison, pages xii

- ↑ I. Asimov, Isaac Asimov, page 72

- ↑ Moskowitz

- ↑ Hell's Cartographers, edited by Brian W. Aldiss and Harry Harrison, page 133

- ↑ New Maps of Hell, Kingsley Amis, page 84

- ↑ Hell's Cartographers, edited by Brian W. Aldiss and Harry Harrison, page 57

- ↑ I. Asimov, Isaac Asimov, page 74

- ↑ Grumbles from the Grave, edited by Virginia Heinlein, page 8

- ↑ Grumbles from the Grave, edited by Virginia Heinlein, page 36

- ↑ Grumbles from the Grave, edited by Virginia Heinlein, page 152

Sources

- Isaac Asimov: I. Asimov: A Memoir, Doubleday, New York, 1994 ISBN 0-385-41701-2

- Sam Moskowitz: "John W. Campbell: The Writing Years", in Amazing Stories, August 1963; Ziff-Davis Publishing Corporation. Reprinted in Seekers of Tomorrow, Masters of Modern Science Fiction, Sam Moskowitz, Ballantine Books, New York, 1967

- Hell's Cartographers, Some Personal Histories of Science Fiction Writers, edited by Brian W. Aldiss and Harry Harrison, Harper & Row, New York, 1975 ISBN 0-06-010052-4

- New Maps of Hell, Kingsley Amis, Ballantine Books, New York, 1960

- The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, edited by John Clute & Peter Nicholls, St. Martin's Press, New York, 1993 ISBN 0-312-09618-6

- Grumbles from the Grave, selected letters of Robert A. Heinlein, edited by Virginia Heinlein, Del Rey Books, New York, 1989 ISBN 0-345-36246-2

- Astounding, edited by Harry Harrison, Random House, New York, 1973 ISBN 0394481674)

- Through Eyes of Wonder, by Ben Bova, Addisonian Press, Reading, Massachusetts, 1975, ISBN 0-201-09206-9

- A Requiem for Astounding, by Alva Rogers, with editorial comments by Harry Bates, F. Orlin Tremaine, and John W. Campbell, Advent:Publishers, Chicago, 1964

- More Issues at Hand, by James Blish, writing as William Atheling, Jr., Advent:Publishers, Inc. Chicago, 1970

- Our Five Days with John W. Campbell, by Joe Green, The Bulletin of the Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America, Fall 2006, No. 171, pages 13–16