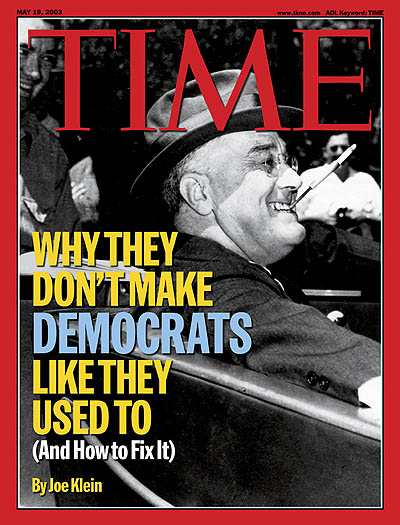

New Deal Coalition

The New Deal coalition was an alliance of voting blocs and interest groups that joined forces in support of President Franklin D. Roosevelt's New Deal program during the 1930s. The coalition was unusually broad in its inclusion of big-city Democratic Party machines, labor unions, minorities (racial, ethnic and religious), liberal farm groups, intellectuals, and the South. It dissolved by the mid-1960s as a result of conservative Democrats, especially in the South, bolting from the party.

Roosevelt's Realignment

The 1932 election brought about a major realignment in political party affiliation, and is widely considered to be a realigning election. Franklin Delano Roosevelt set up his New Deal and forged a coalition of Big City machines, labor unions, liberals, farmers, ethnic and racial minorities (especially Catholics, Jews and African Americans), and Southern whites. These disparate voting blocs together formed a majority of voters and handed the Democratic Party seven victories out of nine presidential elections (1932-36-40-48, 1960, 1964), as well as control of both houses of Congress during all but 4 years 1932-1980 (Republicans won in 1946 and 1952). Starting in the 1930s, the term "liberal" was used in U.S. politics to indicate supporters of the coalition, while "conservative" denoted its opponents. The coalition was never formally organized, and the constituent members often disagreed.

Issues: Equality as core New Deal value

World War Two had a surprisingly small impact on voting patterns. There was no great realignment, except perhaps among German Americans, who moved toward the GOP. The war, however, promoted both the ideology and actuality of shared sacrifice and equality. Heavy income taxes, rationing of basic foods, clothing, and gasoline, and the shutoff of new housing and cars, together with the end of unemployment and very high paying war jobs for the unskilled and semiskilled, made for a radical shift toward economic equality. The index of income inequality shifted dramatically (the richest 5% received 34% of all disposable (after tax) income in 1929, 25% in 1940, and 16% in 1944. [1]

New Dealers, shut out of the war agencies, controlled the price control agency (the OPA), and government propaganda. The wartime propaganda campaigns stressing shared sacrifice and the equality of all soldiers reflected a new consensus of equalitarian thinking. The combination obviously benefited the New Deal, and especially the labor union component of the coalition.[2] The unions seized their opportunity by attacking business for racking off excess profits, and by demanding higher wages in a nationwide wave of strikes in 1946.

Public opinion agreed (in July 1945) with the equalitarian argument about fat cats: 61% though big business owners and executives were paid too much, and 35% added doctors and lawyers. However, only 22% thought factory workers were paid too little, while 33% thought office workers were underpaid. Furthermore, a majority as early as summer 1942 identified "labor leaders" as "taking unfair advantage of the war to get money or power for themselves."[3]

After the war, the unions retained recognition and made some wage gains at the cost of massive defeat of their candidates in 1946, and the passage of the hated Taft-Hartley Act in 1947. By 1946 the Republicans confronted the equality issue head-on in attacking rationing, especially the price controls on meat imposed by Office of Price Administration as an equalitarian device. The issue was a winner for the conservatives, with only 22% of the people supporting the government on this issue.[4]

Party loyalty

In 1948 Truman and his fellow Democrats emphasized party loyalty, knowing they had a clear advantage in the electorate. Partisanship in 1948 was 49% Democratic, 30% Republican, and 22% independent. [5] They also emphasized the New Deal heritage, because the people had fond memories of it. Of Truman supporters, 92% thought the New Deal had done more good than harm, along with 87% of the undecided. Amazingly, a majority of Dewey supporters (54%) agreed. Thus Dewey's strategy of downplaying his disagreements with the New Deal ("me-tooism") was essential.[6]

Class and labor unions

The importance of the union vote grew proportionately to the unions themselves. In 1936, only 7% of the labor force belonged to unions; then came the great organizing drives and by 1940 the total was 16%. The enlarged unionized industries dramatically, pulling up the proportion to 21%. Despite intense fears of a postwar reaction of the sort that had humbled them in the 1920s, union coverage of the non-farm labor force stabilized, and even grew, reaching 23% in 1948.[7] The labor vote divided three ways, CIO, AFL and non-unionized workers.

|

% Democratic Working class, 1936-1948[8] | ||||

| 1936 | 1940 | 1944 | 1948 | |

| Non-Union | 72 | 64 | 56 | 60 |

| AFL | 80 | 71 | 69 | 73 |

| CIO | 85 | 79 | 78 | 76 |

| Union Effect | +8 | +8 | +16 | +14 |

The CIO was younger, more radical and poorer than the better- established AFL, and its membership voted from 3 to 9 points more Democratic than the AFL members. However, both union groups were more Democratic than workers of similar occupations who did not belong to unions, by a factor of 8 to 16 points. That additional union effect can be attributed to the many vigorous get-out-the-Democratic-vote campaigns launched by the unions. They faced the problem of internecine warfare, but with the purging of the Communists in the late 1940s, the AFL and CIO were able to merge in 1955, at about the time union strength reached its peak.[9]

The strong class effects visible in the New Deal elections through 1948 were not just the product of working class action. The middle class played a central role, voting heavily Republican. Probably tax protest was a major motive. By 1952, however, the growing affluence of the working class weakened the protest power of the union vote, while the social mobility of many ethnics enlarged the middle class to include millions of people of Democratic heritage. Class did not quite disappear, but it did mostly fade away.[10]

White Ethnics

The impact of the New Deal and the war on white ethnic groups was enormous, and has not been fully appreciated by historians. In the 1920s they were poor, were ignored politically marginal, and suffered a sharp inferiority complex. Political participation was low among the "new" immigrants (post 1890). The depression his these new immigrants hardest of all, for they had low skill levels and were concentrated in heavy industry. They needed the New Deal and its relief programs came through for them. In terms of politics, the Catholic ethnics were one of the largest and most critical voting blocs in the New Deal coalition. Al Smith's nomination in 1928 had given a strong impetus to registration and voting among Catholics (and, perhaps, Lutherans as well), but that impetus had decayed. Roosevelt held all the Catholics up to 1940. In particular he held the Irish, who included most of the ethnic political leaders, despite Smith's repudiation of the New Deal. The Catholic ethnics were beholden to welfare programs (especially the WPA, PWA and CCC), to city machines, and to labor unions. The Irish, in control in large swaths of most major cities, flourished as never before.[11]

The Italians, despite superficial support for Mussolini, stayed with Roosevelt. [12]

Hispanic voters in the Southwest stared a new level of activity in 1944, but their main surge came with the Viva Kennedy campaign of 1960.[13] The war brought prosperity of the sort never dreamed of, plus an opportunity to demonstrate patriotism in action, in war factories and battlefields.

Jewish voters joined the New Deal coalition late, but by 1936 and 1940 were enthusiastic; despite their rising social-economic status, they never abandoned the party and indeed kept trying to revive the New Deal coalition.[14]

Isolationist sentiment was strong among the Irish, Germans and Italians in 1940. Roosevelt's own personal intervention kept in line such key leaders as Joseph Kennedy and Jim Farley.[15] The Polish vote was of special importance because of its size in such critical cities as Chicago, Milwaukee, Detroit and Buffalo, and because Republicans made a vigorous effort to portray Yalta as a sellout of Polish interests. The Democrats worked hard to retain support, emphasizing class and union issues, and Catholic fears of nativism. The relatively small middle class Polish-American community moved Republican, but the large working class base remained loyal.[16]

Although voting realignments were few, perhaps the largest change came about in 1940, when a large fraction of the German-American voters switched to Wendell Willkie, who of course was of German descent himself. As Willkie crusaded against the anti-business excesses of the New Deal, the Democrats counter-crusaded, arguing that the danger of an internal fifth column was grave, and broadly suggesting that Willkie along with isolationists like Lindbergh was pro-Nazi. Although FDR promised there would be no repeat of the anti-Hun hysteria of the First War, distrust levels were high. Of course, everyone knew what was happening to the Japanese on the West Coast. During the war the federal Office of War Information sponsored numerous polls to monitor possible disloyalty or slackerism. NORC did a study in spring 1942, based on two nationwide surveys. The Germans were slightly more hostile to Britain than non-Germans, and exactly the same versus USSR. People with both parents born in Germany were slightly less hostile to Germany (only 11% wanted to "destroy Germany as a nation" vs 26% of the whole US; only 19% thought Germany has used poison gas in ww2, versus 33%). People with one parent born in Germany were almost exactly like the national average. None of the reports indicated any pro-Nazi sentiment whatever.[17]

African Americans

The political history of African-Americans has been studied primarily through the prism of the Civil Rights movement, with considerable evidence showing the Double-V campaign was successful in mobilizing Democratic votes--war against fascism abroad and discrimination at home. The Republicans, however, continued a strong emphasis on civil rights that kept many traditional supporters in the fold. The Black vote would become critical in the 1960s, but in the 1930s and 1940s it was a junior partner in the coalition, and had little voice or respect.[18]

Regionalism

Regionalism is a relatively neglected theme for the New Deal years, except for the reasonably extensive coverage of the South.[19] The West was a New Deal bastion, which like the South later switched to the GOP.[20] On the other hand, the East was a Republican bastion in the New Deal era. The Middle West has always been a highly competitive battle-ground. Just why the West and East switched is an open question. In the West, heavy immigration surely played a major role. In the East, the story perhaps is that of the downfall of the liberal wing of the GOP.[21]

Cities

Roosevelt had a magnetic appeal to city dwellers, especially the poorer minorities who got recognition, unions, relief jobs and beer thanks to Roosevelt. Taxpayers, small business and the middle class voted for Roosevelt in 1936, but turned sharply against him after the recession of 1937-38 seemed to belie his promises of recovery. [22]

Roosevelt discovered an entirely new use for city machines in his reelection campaigns. Traditionally, local bosses minimized turnout so as to guarantee reliable control of their wards and legislative districts. To carry the electoral college, however, Roosevelt needed massive majorities in the largest cities to overcome the hostility of suburbs and towns. Roosevelt used the Works Progress Administration (1935-1942) as a national political machine through patronage given out by Postmaster General James A. Farley and WPA head Harry Hopkins. Men on relief could get WPA jobs regardless of their politics, but hundreds of thousands of supervisory jobs were given to local Democratic machines; one went to Ronald Reagan's father. The 3.5 million voters on relief payrolls during the 1936 election cast 82% percent of their ballots for Roosevelt. The vibrant labor unions, heavily based in the cities, likewise did their utmost for their benefactor, voting 80% for him, as did Irish, Italian and Jewish voters. In all, the nation's 106 cities over 100,000 population voted 70% for FDR in 1936, compared to 59% elsewhere. Roosevelt won reelection in 1940 thanks to the cities. In the North, the cities over 100,000 gave Roosevelt 60% of their votes, while the rest of the North favored Republican Wendell Willkie by 52%. It was just enough to provide the critical electoral college margin. [23]

With the start of full-scale war mobilization in the summer of 1940, the cities revived. The war economy pumped massive investments into new factories and funded round-the-clock munitions production, guaranteeing a job to anyone who showed up at the factory gate.

End of New Deal coalition

The coalition fell apart in many ways but started with Farley and Roosevelt's break over the third term nominee in 1940. The first cause was lack of a leader of the stature of Roosevelt. The closest was perhaps Lyndon Johnson, who deliberately tried to reinvigorate the old coalition, but in fact drove its constituents apart. New issues such as civil rights, the Vietnam War, abortion, gay rights, affirmative action, and urban riots tended to split the coalition and drive many members away. Meanwhile, the Republican Party made major gains by promising lower taxes and control of crime.

The big-city machines faded away in the 1940s, with a few exceptions, such as Chicago and Albany. The New Deal had made them heavily dependent on the WPA for patronage, and, when Congress shut down the WPA, the cities could not find a substitute. Furthermore, World War II brought such a surge of prosperity that the relief mechanism of the WPA, CCC, etc. was no longer useful as a political tool.[24]

Labor unions crested in size and power in the mid-1950s, then went into steady decline. They continue into the 21st century as major backers of the Democrats, but with so few members they have lost much of their influence.[25]

Intellectuals gave increasing support to Democrats since 1932. The Vietnam War, however, caused a serious split, with the New Left reluctant to support most Democratic presidential candidates.[26]

The European ethnic groups came of age after the 1960s. Ronald Reagan pulled many of the working class social conservatives into the Republican Party as Reagan Democrats. Many middle class ethnics saw the Democratic Party as a working class party and preferred the GOP as the middle class party. In recent years Democratic rhetoric has heavily stressed the "Democrats are for the middle class" theme. The Jewish community still comprises a core Democratic constituency; in 2004 74% voted for Kerry, in 2006 87% voted for Democratic House candidates.[27]

African Americans grew stronger in their Democratic loyalties and in their numbers. By the 1960s, they were a much more important part of the coalition than in the 1930s. Their Democratic loyalties cut across all income and geographic lines to form the single most unified bloc of voters in the country.[28]

1988 election

The challenge for the GOP in 1988 was to hold onto Reagan's coalition for their nominee George Bush, while preventing the revitalization of the New Deal Coalition. Bush won handily over Massachusetts governor Mike Dukakis. In terms of the coalition, Bush carried 60.6% of the white Southerners and 53.0% of the northern white ethnics. He won a relatively high 40.7% of labor union members, but carried only 17.1% of the liberals and 8.0% of the blacks. One reason for Bush's success was his emphasis on cultural issues (like his opposition to abortion and affirmative action), while Dukakis deemphasized social issues and stressed instead his managereial expertise.[29]

Region: Realignment in South

White Southerners abandoned cotton and tobacco farming, and moved to the cities where the New Deal programs had faded away after 1942. Beginning in the 1950s, the southern cities and suburbs started voting Republican in presidential elections. The white South saw the support northern Democrats gave to the Civil Rights Movement as a direct political assault on their interests and opened the way to protest votes for Barry Goldwater, who in 1964 was the first Republican to carry the deep south. Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton lured many of the Southern whites back at the level of Presidential voting, but by 2000 white males in the South were 2-1 Republican and, indeed, formed a major part of the Republican coalition.[30]

In many ways, it was the civil rights movement that ultimately heralded the demise of the coalition. Democrats had traditionally solid support in Southern states (the Solid South), but this electoral dominance began eroding in 1964, when Barry Goldwater carried the Deep South (and little else). In the 1968 election, the South once again abandoned its traditional support for the Democrats by supporting Nixon or segregationist third-party candidate George C. Wallace. Once the segregation ended in 1965, the argument that only southern Democrats could protect segregation faded. The South was no longer dirt poor, rural and dependent on crops like tobacco. As it modernized the Republicans took over the southern states one by one, first at the presidential level, then for Congress, governor and legislature. In 1976 the South rallied behind native son Jimmy Carter, a Democrat; 1992 and 1996 the Democrats nominated two southerners and split the region's electoral votes. By 2000 the region was solidly Republican except for Florida. [31]

Since the 1990s, Democrats solidified their hold on the Northeast and on California, with Republicans holding the south and southwest. The Midwest has been a closely matched battleground for 150 years; Illinois has become much more Democratic, and Minnesota has become less so. Since 1994 the division between the two parties is virtually even in both houses of Congress, as of 2008, and no party has established the kind of dominance that the Democrats were able to exert during the period of the New Deal coalition.

New Deal Coalition: voting %D 1948-1964

| % Democratic vote in major groups, presidency 1948-1964 | |||||

| 1948 | 1952 | 1956 | 1960 | 1964 | |

| all voters | 50 | 45 | 42 | 50 | 61 |

| White | 50 | 43 | 41 | 49 | 59 |

| Black | 50 | 79 | 61 | 68 | 94 |

| College | 22 | 34 | 31 | 39 | 52 |

| High School | 51 | 45 | 42 | 52 | 62 |

| Grade School | 64 | 52 | 50 | 55 | 66 |

| Professional & Business | 19 | 36 | 32 | 42 | 54 |

| White Collar | 47 | 40 | 37 | 48 | 57 |

| Manual worker | 66 | 55 | 50 | 60 | 71 |

| Farmer | 60 | 33 | 46 | 48 | 53 |

| Union member | 76 | 51 | 62 | 77 | |

| Not union | 42 | 35 | 44 | 56 | |

| Protestant | 43 | 37 | 37 | 38 | 55 |

| Catholic | 62 | 56 | 51 | 78 | 76 |

| Republican | 8 | 4 | 5 | 20 | |

| Independent | 35 | 30 | 43 | 56 | |

| Democrat | 77 | 85 | 84 | 87 | |

| East | 48 | 45 | 40 | 53 | 68 |

| Midwest | 50 | 42 | 41 | 48 | 61 |

| West | 49 | 42 | 43 | 49 | 60 |

| South | 53 | 51 | 49 | 51 | 52 |

Source: Gallup Polls in Gallup (1972)

References

- ↑ U.S. Bureau of the census, Historical Statistics of the United States (1976) series G342 p 302; D'Ann Campbell, Women at War With America (1984).

- ↑ Leff (1991)

- ↑ OPOR 52, July 1945, from original cards; OPOR March 1942, in Hadley Cantril and Mildred Strunk, Public Opinion (1951) p. 1176, see also 396-7.

- ↑ See Gallup polls in Cantril and Strunk, Public Opinion, 437, 734

- ↑ from AIPO #429, after adjusting for biases regarding education and city size; see also Everett Carl Ladd and Charles Hadley, Transformations of the American Party System (1975), 123, 321.

- ↑ AIPO 429. On Truman's aggressively liberal strategy, see Sean J. Savage, Truman and the Democratic Party (1997).

- ↑ Historical Statistics 178.

- ↑ George Gallup, The Political Almanac: 1952 (1952) 37

- ↑ Irving Bernstein, The Turbulent Years (1970); Robert H. Zieger, The CIO, 1935-1955 (1995); Steven Fraser, Labor Will Rule: Sidney Hillman and the Rise of American Labor (1991).

- ↑ Ladd and Hadley, 234; Norval D. Glenn, "Class And Party Support In The United States: Recent and Emerging Trends." Public Opinion Quarterly 1973 37(1): 1-20; Michael Hout, Clem Brooks, and Jeff Manza, "The Democratic Class Struggle in the United States, 1948-1992" American Sociological Review 1995 60(6): 805- 828; Avery M. Guest, "Class Consciousness And American Political Attitudes." Social Forces 1974 52(4): 496-510.

- ↑ . Patrick D. Kennedy, "Chicago's Irish Americans And The Candidacies Of Franklin D. Roosevelt, 1932-1944." Illinois Historical Journal (1995) 88(4): 263-278. The best study of ethnic and religious voting is James C. Mott, "The Fate of an Alliance: The Roosevelt Coalition, 1932-1952," (PhD, U of Illinois-Chicago, 1988).

- ↑ See Rudolph J. Vecoli, "The Coming Of Age Of Italian Americans: 1945-1974," Ethnicity 1978 5(2): 119-147; and Stefano Luconi, "Machine Politics and the Consolidation of the Roosevelt Majority: The Case of Italian Americans in Pittsburgh and Philadelphia," Journal of American Ethnic History, 1996 15(2): 32-59.

- ↑ Mario T. Garcia, "Americans All: The Mexican American Generation and the Politics Of Wartime Los Angeles, 1941-45," Social Science Quarterly 1984 65(2): 278-289.

- ↑ Mott, "The Fate of an Alliance", 60-69; Ladd and Hadley, Transformations, 60-64; Leonard Dinnerstein, "Jews And The New Deal," American Jewish History 1983 72(4): 461-476; Alan M. Fisher, "Realignment Of The Jewish Vote?" Political Science Quarterly (1979) 94(1): 97-116.

- ↑ Michael Beschloss, Kennedy and Roosevelt: The Uneasy Alliance (1980); Thomas T. Spencer, "'Old' Democrats And New Deal Politics: Claude G. Bowers, James A. Farley, And The Changing Democratic Party, 1933- 1940," Indiana Magazine Of History 1996 92(1): 26-45.

- ↑ Jack L. Hammersmith, "Franklin Roosevelt, the Polish Question, and the Election of 1944," Mid-America 1977 59(1): 5-17; Robert D. Ubriaco, Jr., "Bread And Butter Politics Or Foreign Policy Concerns? Class Versus Ethnicity In The Midwestern Polish American Community During The 1946 Congressional Elections," Polish American Studies 1994 51(2): 5-32.

- ↑ "A Study of the Effect of German and Italian Origin on Certain War Attitudes" (NORC special Report #6, copy in NORC, U Chicago).

- ↑ William J. McKenna, "The Negro Vote In Philadelphia Elections," Pennsylvania History 1965 32(4): 406-415; Ladd and Hadley, 60; James J. Kenneally, "Black Republicans During The New Deal: The Role Of Joseph W. Martin, Jr.," Review of Politics 1993 55(1): 117-139; Harvard Sitkoff, A New Deal for Blacks (1981); Nancy J. Weiss, Farewell to the Party of Lincoln: Black Politics in the Age of FDR (1983), stresses the welfare program as critical to the realignment.

- ↑ George Brown Tindall, Disruption of the Solid South (1992); Tindall, The Emergence of the New South, 1913-1945 (1967); Numan V. Bartley, The New South, 1945-1980 (1995); Earl Black and Merle Black, The Rise of Southern Republicans (2003); William E. Leuchtenburg, The White House Looks South: Franklin D. Roosevelt, Harry S. Truman, Lyndon B. Johnson (2005)

- ↑ Gerald D. Nash, American West Transformed: The Impact of the Second World War (1990); Peter F. Galderisi et al., The Politics of Realignment: Party Change in the Mountain West (1987); Heinz Eulau, The Western Public: 1952 and Beyond (1954); James Q. Wilson, "A Guide To Reagan Country. The Political Culture Of Southern California," Commentary 1967 43(5): 37-45.

- ↑ Nicol C. Rae, The Decline and Fall of the Liberal Republicans: From 1952 to the Present (1989).

- ↑ Jensen 1981

- ↑ Jensen 1981

- ↑ Erie, Rainbow's End (1988).

- ↑ Stanley Aronowitz, From the Ashes of the Old: American Labor and America's Future (1998) ch. 7

- ↑ Tevi Troy, Intellectuals and the American Presidency: Philosophers, Jesters, or Technicians? (2003)

- ↑ William B. Prendergast, The Catholic Voter in American Politics: The Passing of the Democratic Monolith, (1999). Exit polls from CNN at [1]

- ↑ Hanes Walton, African American Power and Politics: The Political Context Variable (1997)

- ↑ Joel Lieske, "Cultural Issues and Images in the 1988 Presidential Campaign: Why the Democrats Lost. Again!," PS: Political Science and Politics, Vol. 24, No. 2. (Jun., 1991), pp. 180-187, esp. p. 182. in JSTOR

- ↑ Earl Black and Merle Black, Politics and Society in the South, 1987.

- ↑ Thomas F. Schaller, Whistling Past Dixie: How Democrats Can Win Without the South (2006)