Gustavus Franklin Swift

Gustavus Franklin Swift (June 24, 1839–March 29, 1903) was an American entrepreneur who founded a meat-packing empire in the Midwest during the late 19th Century, over which he presided until his death. He is credited with the development of the first practical ice-cooled railroad car which allowed his company to ship dressed meats to all parts of the country and even abroad, which ushered in the "era of cheap beef." Swift pioneered the use of animal by-products for the manufacture of soap, glue, fertilizer, various types of sundries, even medical products. Swift generously donated large sums of money to such institutions as the University of Chicago, the Methodist Episcopal Church, and the Young Men's Christian Association (YMCA). He established Northwestern University's "School of Oratory" in memory of his daughter, Annie May Swift, who died while attending the school. When he died in 1903, his company was valued at between $25 million and $35 million, and had a workforce that was more than 21,000 strong. "The House of Swift" slaughtered as many as two million cattle, four million hogs, and two million sheep a year. Three years after his death, the value of the company's capital stock topped $50 million.

The early years

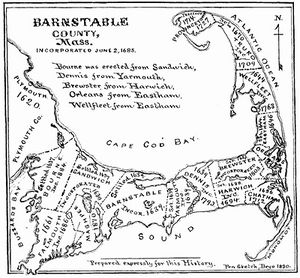

Swift was the second of three boys born to William Swift and Sally Crowell, descendants of British settlers who immigrated to New England in the 17th Century. The family (which included Gustavus’ brothers Noble and Edwin) lived and worked on a farm in the Cape Cod town of West Sandwich, Massachusetts (present-day Sagamore), where they raised and slaughtered cattle, sheep, and hogs. As a boy, Swift took little interest in his studies and consequently left the nearby country school after only eight years. During that period he was employed in a number of odd jobs, finally finding full-time work in his elder brother Noble's butcher shop at the age of fourteen. Two years later, in 1855, he opened his own cattle and pork butchering business with the help of small loans from his family. Swift purchased livestock at the market in Brighton and drove them to Eastham, a ten-day journey. A shrewd businessman, he purportedly followed the somewhat common practice of denying his herds water during the last miles of the trip so that they would drink large quantities of liquid once they reached their final destination, effectively boosting their weights. Swift married Annie Maria Higgins of North Eastham in 1861.

Over the years Annie gave birth to a total of eleven children, nine of whom reached adulthood. In 1862 Swift and his new bride opened a small butcher shop and slaughterhouse. Seven years later Gustavus and Annie moved the family to Brighton (near Boston), where in 1872 Swift became partner in a new venture, Hathaway and Swift. Swift and partner James A. Hathaway (a renowned Boston meat dealer) initially relocated the company to Albany, then almost immediately thereafter to Buffalo. An astute cattle-buyer, Swift followed the market steadily westward. On his recommendation, Hathaway and Swift moved once more in 1875, this time to join the influx of meat packers setting up shop in Chicago's sprawling Union Stock Yards. Swift established himself as one of the dominant figures of "The Yards", and his distinctive delivery wagons became familiar fixtures on Chicago's streets. In 1878 his partnership with Hathaway dissolved and "Swift Bros. and Company" was formed in partnership with younger brother Edwin. The company became a driving force in the Chicago meat packing industry, and was incorporated in 1885 as "Swift & Co." with $300,000 in capital stock and Gustavus Swift as president. It is from this position that Swift led the way in revolutionizing how meat was processed, delivered, and sold.

Chicago and the birth of the meat-packing industry

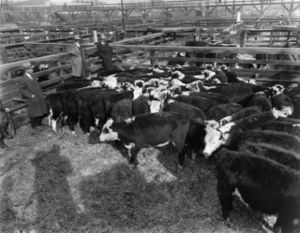

Following the end of the American Civil War, Chicago emerged as a major railway center, making it an ideal point for the distribution of livestock raised on the Great Plains to Eastern markets.[1] Getting the animals to market required herds to be driven distances of up to twelve hundred miles to railheads in Kansas City, whereupon they were loaded into specialized stock cars and transported live ("on the hoof") to regional processing centers. Driving cattle across the plains also led to tremendous weight loss, and a number of animals were typically lost along the way. Upon arrival at the local processing facility, livestock were either slaughtered by wholesalers and delivered fresh to nearby butcher shops for retail sale, smoked, or packed for shipment in barrels of salt. Certain costly inefficiencies were inherent in the process of transporting live animals by rail, particularly due to the fact that some sixty percent of the animal's mass is composed of inedible matter. Many animals weakened by the long drive died in transit, further increasing the per-unit shipping cost. Swift's ultimate solution to these problems was to devise a method to ship dressed meats from his packing plant in Chicago to the East.

The advent of the refrigerator car

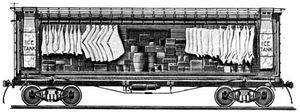

An early refrigerator car design, circa 1870. Hatches in the roof provided access to the ice tanks at each end of the car.

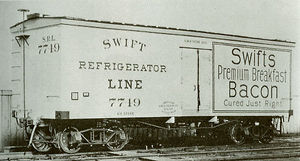

A builder's photo of one of the first refrigerator cars to come out of the Detroit plant of the American Car and Foundry Company (ACF), built in 1899 for the Swift Refrigerator Line.

A Swift refrigerator car has reached the end-of-the-line at East Orange, New Jersey. The car has been repainted and was photographed in mid- or late-1937, after the use of "billboard" advertising on freight cars had been banned by the Interstate Commerce Commission, and such cars could no longer be accepted for interchange between roads.

A number of attempts were made during the mid-1800s to ship agricultural products via rail car. As early as 1842 the Western Railroad of Massachusetts was reported in the June 15 edition of the Boston Traveler to be experimenting with innovative freight car designs capable of carrying all types of perishable goods without spoilage.[2] The first known refrigerated boxcar or "reefer" entered service on the Northern Railroad of New York (or NRNY, which became part of the Rutland Railroad) in June 1851. This "icebox on wheels" was a limited success in that it was only able to function in cold weather. That same year, the Ogdensburg & Lake Champlain Railroad (O&LC) began shipping butter to Boston in purpose-built freight cars, utilizing ice to cool the contents. The first consignment of dressed beef to ever leave the Chicago stockyards did so in 1857, and was carried in ordinary boxcars retrofitted with bins filled with ice. Placing the meat directly against ice resulted in discoloration and affected the taste, however, and therefore proved to be impractical. During the same period Swift experimented by moving cut meat using a string of ten boxcars which ran with their doors removed, and made a few test shipments to New York during the winter months over the Grand Trunk Railroad (GTR). The method proved too limited to be profitable.

Detroit's William Davis patented a refrigerator car that employed metal racks to suspend the carcasses above a frozen mixture of ice and salt. He sold the design in 1868 to George Hammond, a Chicago meat-packer, who built a set of cars to transport his products to Boston. The loads had the unfortunate tendency of swinging to one side when the car entered a curve at high speed, and the use of the units was discontinued after several derailments. Finally, in 1878, Swift hired engineer Andrew Chase to design a ventilated car that was well-insulated, and positioned the ice in a compartment at the top of the car, allowing the chilled air to flow naturally downward..[3] The meat was packed tightly at the bottom of the car to keep the center of gravity low and to prevent the cargo from shifting. Chase's design proved to be a practical solution to providing temperature-controlled carriage of dressed meats, and allowed Swift & Company to ship their products all over the United States, and even internationally, and in doing so radically altered the meat business.

Swift's attempts to sell this design to the major railroads were unanimously rebuffed as the companies feared that they would jeopardize their considerable investments in stock cars and animal pens if refrigerated meat transport gained wide acceptance. In response, Swift financed the initial production run on his own, then — when the American roads refused his business — he contracted with the GTR (a railroad that derived little income from transporting live cattle) to haul them into Michigan and then eastward through Canada. In 1880 the Peninsular Car Company (subsequently purchased by ACF) delivered to Swift the first of these units, and the Swift Refrigerator Line (SRL) was created. Within a year the Line’s roster had risen to nearly 200 units, and Swift was transporting an average of 3,000 carcasses a week to Boston. Competing firms such as Armour and Company quickly followed suit. By 1920 the SRL owned and operated 7,000 of the ice-cooled rail cars. The General American Transportation Corporation would assume ownership of the line in 1930.

Live cattle and dressed beef deliveries to New York (tons):

| (Stock Cars) | (Refrigerator Cars) | |

| Year | Live Cattle | Dressed Beef |

| 1882 | 366,487 | 2,633 |

| 1883 | 392,095 | 16,365 |

| 1884 | 328,220 | 34,956 |

| 1885 | 337,820 | 53,344 |

| 1886 | 280,184 | 69,769 |

The subject cars travelled on the Erie, Lackawanna, New York Central, and Pennsylvania railroads.

Source: Railway Review, January 29, 1887, p. 62.

Expansion of an empire

Swift’s initial efforts to ship dressed beef from Chicago to the East Coast met with resistance from local meat retailers, who questioned the safety of meat that had been slaughtered and dressed weeks earlier, and then transported hundreds of miles. In 1886 the "National Butchers' Protective Association" was formed for the purpose of organizing boycotts against Swift's products. A massive advertising campaign helped to overcome the skepticism of a public who soon came to prefer the low-cost, high-quality Swift meats, a trend that almost certainly forced some butcher's shops out of business. To achieve market penetration, Swift established "peddler car routes" to convey dressed meat in smaller amounts to out-of-the-way towns and villages. So sharply did Swift cut costs, and so vastly did he increase production, that his firm was able to market meat not only throughout the continental United States, but also in Honolulu, Tokyo, Osaka, Manila, Singapore, Shanghai, Hong Kong, and Great Britain. Over the next few years, Swift concentrated his efforts on creating a nationwide distribution and marketing organization. Expanding production facilities and the increasing availability of refrigerated rail service necessitated the construction of cold storage warehouses, both at the slaughterhouses and at the end-of-line distribution points. Ice blocks, most of them cut from the surface of the Great Lakes, kept the meat lockers cool during the summer months.[4] Between 1888 and 1892 Swift & Co. constructed packing plants in the following cities:

- Sioux City, Iowa

- Kansas City, Missouri

- Saint Joseph, Missouri

- Saint Louis, Missouri

- South Saint Paul, Minnesota

- South Omaha, Nebraska

- Fort Worth, Texas and

- South San Francisco, California (which Swift helped found, and name).

In order to protect his supply lines, Swift organized the stockyards to facilitate the purchase of large numbers of animals on a regular and orderly basis. In 1902 Swift joined with fellow meat packers J. Ogden Armour and Edward Morris, along with the investment banking firm of Kuhn, Loeb, and Company, to create the National Packing Company for the purpose of fixing prices, dividing up markets, and suppressing union efforts to organize industry workers. The group became known as the "Meat Trust" and the "Big Four" of the meat packing industry, and developed such a monopoly that the United States Supreme Court ordered the venture to disband in 1905.

"Everything but the squeal..."

This interior view of a meat packing house shows men working with pork carcasses and viscera, sometime between 1910 and 1930.

A view of the Swift Brands Sioux City, Iowa meat packing plant, circa 1917. All but one of the refrigerator cars in the photo bear the markings of the Swift Refrigerator Line.

In response to public outcries to reduce the amount of pollutants generated by his packing plants, Swift sought innovative ways to use previously discarded portions of the animals his company butchered. This practice led to the wide scale commercial production of such diverse products as oleomargarine, soap, glue, fertilizer, hairbrushes, buttons, knife handles, and pharmaceutical preparations such as pepsin and insulin. Low-grade meats were canned in products like pork and beans. The absence of federal inspection led to abuses. Sausages might incorporate rat droppings, dead rodents, or sawdust, and meat that had spoiled or meat mixed with waste materials was sometimes packed and sold (Swift once bragged that his slaughterhouses had become so sophisticated that they utilized "...everything but the squeal..."). Transgressions such as these were first documented in Upton Sinclair's novel The Jungle, the publication of which shocked the nation and led to the passing of the Federal Meat Inspection Act of 1906.[5]

Vertical integration

The meat packing plants of Chicago were among the first to utilize assembly-line (or in this case, disassembly-line) production techniques.[6] Henry Ford states in his autobiography My Life and Work that it was a visit to a Chicago slaughterhouse which opened his eyes to the virtues of employing a moving conveyor system and fixed work stations in industrial applications. These practices symbolize the concept of "rationalized organization of work" to this day. Swift adapted the methods of the industrial revolution to meat packing operations, which resulted in huge efficiencies by allowing his plants to produce at a massive scale. The work was divided into a myriad of specific sub-tasks, which were carried out under the direction of supervisory personnel. Swift & Co. was broken down organizationally into various divisions, each one responsible for conducting a different aspect of the business of "bringing meat from the ranch to the consumer." By developing a vertically-integrated company, Swift was able to control the sale of his meats from the slaughterhouse to the local butcher shop.[7] Swift devoted a great deal of time to indoctrinating employees and teaching them the company’s methods and policies. He also motivated his employees to focus on the company's profit goals by adhering to a strict policy of promotion from within.

The innovations that Swift championed not only revolutionized the meat packing industry, but also played a vital role in establishing the modern American business system, with an emphasis on mass production, functional specialization, managerial expertise, national distribution networks, and adaptation to technological innovation. Upon his death Swift was laid to rest in the family mausoleum at Mount Hope Cemetery in Chicago.