Indonesia

| Republic of Indonesia | |

|---|---|

| Republik Indonesia | |

| |

| |

| Motto | "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika" (Old Javanese) "Unity in Diversity" National ideology: Pancasila |

| National anthem | Indonesia Raya |

| Capital | Jakarta |

| Largest city | Jakarta |

| Official language | Indonesian |

| Government type | Republic |

| President | Susilo Bambang Yudhoyono |

| Vice President | Jusuf Kalla |

| Area | 1,904,569 km² 735,355 mi² (16th) (4.85 % water) |

| Population | 222,781,000 (4th) (2005 estimate) 206,264,595 (2000 census) |

| Population density | 117/km² (84th) 303 mi² |

| GDP (PPP) | Total:US$977.4 billion (15th) Per capita:US$4,458[1] (110th) (2005 estimate) |

| HDI | Template:Increase 0.711 (medium) (108th) (2004) |

| Currency | Rupiah (IDR) |

| Time zone | various (UTC+7 to +9) Summer:not observed |

| Country codes | Internet TLD : .id Calling code : +62 |

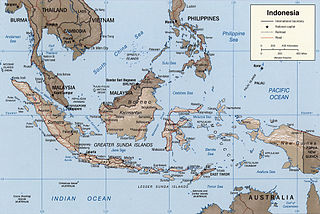

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia (Indonesian: Republik Indonesia), is a nation of 17,508 islands[2] in the South East Asian archipelago, making it the world's largest archipelagic state. With a population of over 200 million, it is the world's fourth most populous country and the most populous Muslim-majority nation. Indonesia is the world's third largest democracy after India and the USA. Its capital is Jakarta and it shares land borders with Papua New Guinea, East Timor, and Malaysia.

The Indonesian Archipelago, home of the Spice Islands, has been an important trade destination since Chinese sailors first profited from the spice trade in ancient times. Indonesia's history has been influenced by numerous foreign powers that were drawn to the archipelago by its wealth of natural resources; these have included Indians, under whose influence Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms flourished beginning in the early centuries AD, Muslim traders who spread Islam in medieval times, and Europeans who fought for monopolization of the spice trade during the Age of Exploration. Indonesia was colonized by the Dutch for over three centuries; however, the nation declared its independence in 1945, which was internationally recognized four years later. Indonesia's post-independence history has been turbulent, with political instability and corruption, periods of rapid economic growth and decline, environmental catastrophe, and a recent democratization process.

Indonesia is a unitary state consisting of numerous distinct ethnic, linguistic, and religious groups spread across its numerous islands. A shared history of colonialism, rebellion against it, a national language, and a Muslim majority population help to define Indonesia as a state. Indonesia's national motto, "Bhinneka tunggal ika" ("Unity in diversity", derived from Old Javanese), reflects the amalgamation of a myriad cultures, languages, and ethnic groups that shape every aspect of the country. Sectarian tensions, however, have threatened political stability in some regions, leading to violent confrontations.

Etymology

The name Indonesia was derived from Greek indus, meaning "India", and nesos, meaning "islands".[3] Dating back to the eighteenth century, the name far predates the formation of the Indonesian nation.[4] In 1850, an English ethnologist George Earl proposed to call the inhabitants of "Indian Archipelago or Malayan Archipelago" as either "Indunesians" or "Malayunesians"; preferring the latter term.[5] J.C. Logan, Earl's student, used "Indonesia" in the same publication as a synonym for "Indian Archipelago".[6] The Dutch academics who had an important position for the East Indies publications, however, were reluctant to use "Indonesia".[7] They used either the term of "Malay Archipelago" (Maleische Archipel), the "Netherlands East Indies" (Nederlandsch Oost Indïes), popularly Indïe, "the East" (de Oost) or even Insulinde, a term introduced in a novel by Max Havelaar in 1860. After 1900, the term Indonesia began to spread in academic circles outside the Netherlands, and Indonesian nationalist groups began to use the term for their political expression.[7] The first Indonesian scholar to use the name was Suwardi Suryaningrat (Ki Hajar Dewantara) when he established a press bureau with the name of Indonesisch Pers-bureau in the Netherlands in 1913.[4]

History

Fossil evidence suggests the Indonesian archipelago was inhabited by Homo erectus,[8] popularly termed the "Java Man". Estimates of its existence range from 500,000[9] to 2 million years ago.[10] The Austronesian people who form the majority of todays population, migrated to South East Asia from Taiwan and first arrived in Indonesia around 2,000 BC, relegating an existing population of Melanesian people to the far eastern regions as they expanded. Ideal agricultural conditions and the mastering of wet-field rice cultivation as early as the seventh century BC allowed villages, towns, and eventually small kingdoms to flourish by the first century AD. Around the same time, the region established trade between both India and China. Fostered by Indonesia’s strategic sea-lane position, trade continued to be one of the most important influences on the country’s history.

It was upon this trade, and the Hinduism and Buddhism that was brought with it, that the Sriwijaya kingdom flourished from the seventh century AD. It became a powerful naval state, growing wealthy on the international trade it controlled through the region until its decline in the twelfth century. During the eighth and tenth centuries AD, the agriculturally-based Buddhist Sailendra and Hindu Mataram dynasties thrived and declined in inland Java with grand monuments built, including Borobudur and Prambanan respectively. The Hindu Majapahit kingdom was founded in eastern Java in 1294, and under its military commander Gajah Mada stretched over much of modern day Indonesia in 1350. This period is referred to as a "Golden Age" in the country’s history.[11]

Arab traders first brought Islam to Indonesia in the late twelfth century, establishing settlements in the Aceh region. It spread across the Indonesian archipelago, following trade routes. Rather than a violent conquest, it was, for the most part, peacefully laid over and mixed with existing cultural and religious influences shaping what is still the predominant form of Islam in Indonesia, particularly in Java. European traders first arrived in the early sixteenth century seeking to monopolize the sources of nutmeg, cloves, and cubeb pepper in The Moluccas. In 1512, the Portuguese, led by Francisco Serrão, were the first Europeans to arrive in Indonesia;[12] the Dutch and British followed. The Dutch became the dominant traders in Indonesia, establishing the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in 1602. Following bankruptcy, however, the VOC was formally dissolved in 1800 and the government of the Netherlands established the Dutch East Indies as a fully-fledged colony.[12]

The Dutch colonial presence in Indonesia existed in various forms for over three hundred years until the Japanese occupation during World War II.[13][14] During the war, Sukarno, a popular leader of the Indonesian Nationalist Party, cooperated with the occupying Japanese with the intention of strengthening the independence movement.[15] On 17 August 1945, two days after the Japanese surrender, Sukarno unilaterally declared Indonesian independence.[16][17] Sukarno was declared the first president and Muhammad Hatta the vice-president. Over the next four years, a bitter armed conflict was fought as the Netherlands tried to win back its colony; in the face of international pressure, the Netherlands recognised Indonesian independence in 1949.[17][18]

Sukarno's presidency relied on balancing the often opposing forces of the Military, Islam and Communism. Increasing tensions, however, between the powerful Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) and the Military culminated in an abortive coup on 30 September 1965, during which six top-ranking generals were murdered in contentious circumstances. A quick counter-coup led by Major General Suharto resulted in a violent anti-communist purge centered mainly in Java and Bali. Hundreds of thousands were killed[19] – the exact figure is uncertain with estimates ranging from 100,000 to as many as two million[20] – and the dominant PKI was in effect destroyed. Politically, Suharto capitalized on Sukarno's gravely weakened position; by March 1967, he had maneuvered himself into the presidency in a drawn out power play between the two. Commonly referred to as the "New Order",[21] Suharto's administration encouraged foreign investment in Indonesia, which become a major factor in the subsequent three decades of substantial economic growth.

In 1997-98, however, Indonesia was the country hardest hit by the East Asian Financial Crisis. This aggravated popular discontent with Suharto, who was already facing accusations of corruption. Popular protests against his now weakened presidency broke out in early 1998[22] and on 21 May 1998, Suharto announced his resignation, ushering in the Reformasi era in Indonesia.[23] East Timor voted to secede from Indonesia in 1999, following the 1975 invasion and subsequent twenty-five-year occupation marked by repression and human rights abuses, for which Indonesia was internationally condemned.[24][25]

A wide range of reforms have been introduced since Suharto's resignation, including Indonesia's first direct presidential election in 2004, although progress has been slowed by political and economic instability, social unrest, terrorism and recent natural disasters. Although relations among different religious and ethnic groups are largely harmonious, acute sectarian discontent, even violence, remains a problem in some areas.[26] A political settlement to an armed separatist conflict in Aceh was achieved in 2005.[27]

Government and politics

Structure and affiliations

Indonesia is a republic with presidential system. Being a unitary state, power is concentrated in the national government. Following the downfall of the Suharto administration in 1998, Indonesian political and governmental structures have undergone major reforms. The 1945 Constitution of Indonesia has been amended four times in 1999, 2000, 2001 and 2002. Executive, judicial and legislative branches were revamped, creating a newly liberal democratic political system.[28]

The President of Indonesia is the head of state, commander-in-chief of the Indonesian armed forces, and responsible for domestic governance, policy-making and foreign affairs. The president appoints a council of ministers, who are not required to be elected members of the legislature. The 2004 presidential election was the first time the people directly voted for President and Vice President.[29][30] Presidential terms are five years and limited to a maximum of two consecutive terms.[31]

The highest representative body at national level is the People's Consultative Assembly (MPR). Its main functions include supporting and amending the Constitution, inauguration of the President and the fomalization of broad outlines of state policy; MPR has the power to impeach the President.[32] MPR contains two lower house of representatives: the People's Representative Council (DPR) with 550 members and the Regional Representatives Council (DPD) with 168 members.

The DPR is the legislative body which passes legislations and monitors the executive branch. Members of the DPR are elected for five-year terms on a proportional representation basis from more than two thousand electoral districts.[28] Since 1998, the DPR's role has increased markedly, including a total control of statutes production without executive branch interventions, all members are now elected (no reserved seats for military personnel) and some fundamental rights exclusive for DPR.[28][33] The DPD is a new chamber, based on the 2001 constitution amendment. Its members are representatives from the thirty-three provinces; each has four non-partisan representatives. DPD represents regional areas within national politics and its role is restricted to bills concerning matters of regional management.[34] During the legislative general election, each citizen votes for members of DPR through political parties, DPD members through individual names, and members of the provincial and local Regional People's Representative Councils (DPRD).[28]

The Indonesia judicial system comprises several courts; the highest is the Supreme Court. Most civil disputes appear first before a State Court; from which appeals can be heard before the High Court. The Supreme Court can hear a final cassation appeal or conduct a case review if there is new evidence. Apart from civil courts, Indonesia has a Commercial Court to handle bankruptcy and insolvency; a State Administrative Court to hear administrative law cases against the government; a Constitutional Court to hear disputes concerning legality of law products, general elections, dissolution of political parties, and the scope of authority of a state institution; and a Religious Court to deal with specific religious cases.

Indonesia's armed forces (TNI) total about 300,000 members, including the Army (TNI-AD), Navy (including marines), and Air Force. The army has about 233,000 active-duty personnel. Defence spending in the national budget is 3% of GDP supplemented by revenue from military-run businesses and foundations. In the post-Suharto period since 1998, formal TNI representation in parliament has been removed, but its political influence remains extensive.

Contemporary issues

As of 2006, an estimated 17.8% of the population live below the poverty line and 49.0% of the population live on less than US$2 per day.[35] The East Asian financial crisis of 1998 severely increased levels of poverty. The average annual growth rate of 5% in recent years is not enough, however, to make a significant impact on unemployment.[36] In 2005, the Government was forced to reduce its large subsidies on fuel prices drastically as international oil prices climbed, which, combined with stagnant wages growth and increasing rice prices, have worsened poverty levels. Another stated Government priority is to stamp out corruption, which significantly raises producers' costs and deters investment.[33]

Significant separatist movements in the provinces of Aceh and Papua have led to armed conflict and allegations of human rights abuses. Following a long standing guerrilla war between the Free Aceh Movement (GAM) and the Indonesian military, a ceasefire agreement was reached in 2005. In Papua, there has been a significant, albeit imperfect, implementation of regional autonomy laws, and a reported decline in the levels of violence and human rights abuses.[37][38]

Terrorist bombings linked to extreme Islamism and Al-Qaeda[39] have occurred in Bali and Jakarta; the most deadly attack came in 2002, killing 202 people (including 164 international tourists) in the resort town of Kuta.[40] The attacks and travel warnings issued by other countries have severely damaged the country’s important tourist industry and the economy's foreign investment prospects.[41] In cooperation with other countries, the Government has achieved substantial, but so far incomplete, success in apprehending and prosecuting the perpetrators and fracturing their organizations.[42]

In the freer political environment of the post-Suharto years, the role of religion, particularly Islam, in society and politics is hotly debated. The current "anti-pornography" bill before Parliament, for example, is aimed not only at publications and movies, but also at outlawing immodest dress and displays of affection such as kissing in public and dancing. Its supporters argue that it is a necessity to maintain moral standards; its detractors maintain it would be an unwelcome control of individual freedoms and would be discriminatory towards women in particular.[43]

Administrative divisions

Indonesia has thirty-three provinces, three of which have special status, and a special capital region. Each province has its own political legislature and is headed by a governor. The provinces are subdivided into regencies (kabupaten) and cities (kotamadya), which are further subdivided into subdistricts (kecamatan), and again into village groupings. Following the implementation of regional autonomy measures in 2001, the 440 districts or regencies have become the key administrative units responsible for providing most government services. The village administration level is influential handling matters of a village or neighbourhood by an elected lurah or kepala desa (village chief).

Indonesian provinces and their capitals

(Indonesian name in brackets where different to English)

* indicates province with Special Status

Four provinces have special status; Aceh, Jakarta, Yogyakarta and Papua. Special status provides legislative privileges and more autonomy from the central government in comparison to other provinces. The Acehnese government, for example, has the right to create an independent legal system; in 2003, it instituted a form of sharia (Islamic law).[44] Yogyakarta was granted as a special territory as an award for its role during the Indonesian War of Independence;[45] the positions of governor and its vice governor are prioritized for descendants of the Sultan of Yogyakarta and Paku Alam, respectively,[46] much like a sultanate. Papua, formerly known as Irian Jaya, has had special status since 2001.[47] Jakarta is the country's special capital region.

Geography

Indonesia's 17,508 islands, about 6,000 of which are inhabited, are scattered around the equator. The five main islands are Java, Sumatra, Kalimantan (the Indonesian part of Borneo), New Guinea (shared with Papua New Guinea) and Sulawesi. Indonesia borders Malaysia on the island of Borneo (Indonesian, Papua New Guinea on the island of New Guinea and East Timor on the island of Timor. The capital Jakarta is on Java and is the nation's largest city, followed by Surabaya, Bandung, Medan, and Semarang.

At 1,919,440 km² (741,050 mi²), Indonesia is the world's sixteenth-largest country in terms of land area.[48] Its population density is 134.39 people per square kilometer, 79th in the world.[49] At 4,884 meters (12,405 feet), Puncak Jaya in Papua is Indonesia's highest peak and Lake Toba in Sumatra its largest lake with an area of 1,145 km² (442 mi²). The country's largest rivers are in Kalimantan and include the Mahakam, and Barito. With their sources in the island’s central massif, they meander through swamps to the sea allowing communication and transport between settlements built along their edges.[50]

Its location on the edges of three tectonic plates, specifically the Pacific, Eurasian, and Australian plates, makes Indonesia a site of numerous volcanoes and frequent earthquakes. Indonesia has at least 66 volcanoes,[51] including Krakatoa and Tambora both famous for their devastating eruptions in the nineteenth century. The eruption of the Toba supervolcano 71,500 ± 4000 years ago was one of the largest eruptions known and a global catastrophe. Recent disasters due to seismic activity include the tsunami in Aceh in 2004 and the Yogyakarta earthquake in 2006. Volcanic ash, however, is a major contributor to the high agricultural fertility that has historically sustained significantly high population density on the islands of Java and Bali.[52]

Equatorial Indonesia has a tropical climate with two distinct monsoonal wet and dry seasons. Average annual rainfall in the lowlands varies from 1,780 to 3,175 millimetres (70 to 125 inches), and up to 6,100 millimetres (240 inches) in mountainous regions. The mountainous west coast of Sumatra western Java, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, and Papua receive the highest rainfall. Humidity is generally high, averaging about 80%. Temperatures vary little over the year; the average daily temperature range of Jakarta is 21° to 33° Celsius (69° to 92° Fahrenheit).

Ecology

Indonesia’s vast size, tropical climate and archipelagic geography, supports the world's second highest level of biodiversity (after Brazil); 45% of the country is covered by forests[53] and its flora and fauna is a mixture of Asian and Australasian species.[54] Once linked to the Asian mainland, the Greater Sunda Islands (Sumatra, Kalimantan, Java and Bali) have a wealth of Asian fauna. Large species such as the tiger, rhinoceros, orangutan, elephant, and leopard, although once abundant and distributed east as far as Bali, have dwindled drastically in number and distribution. Sumatra and Kalimantan still contain vast forests, predominantly of Asian species, but they are being logged at rapid rates. In contrast, the forests of smaller but densely populated Java have largely been removed for human habitation and agriculture. Sulawesi,[55] Nusa Tenggara and Maluku,[56] having been long separated from the continental landmasses, have developed their own unique flora and fauna. Originally part of the Australian landmass, the highlands of Papua have a number of unique environments, including over six hundred bird species, with fauna closely related to that of Australia.[57]

Surrounding thousands of islands with over 80,000 kilometers of coastline, the warm, tropical seas of Indonesia also boast a high level of biodiversity,[3] with a corresponding diverse range of ecosystems that include beaches, sand dunes, estuaries, mangroves, coral reefs, sea grass beds, coastal mudflats, tidal flats, algal beds, and small island ecosystems.

The British naturalist Alfred Wallace described a dividing line between the distribution of Indonesia's Asian and Australasian species.[58] Known as the "Wallace Line", it runs roughly north-south along the edge of the Sunda shelf, between Kalimantan and Sulawesi, and then down along the deep Lombok Strait, between Lombok and Bali. West of the line the flora and fauna are more Asian; moving east from Lombok, they are increasingly Australian. Wallace described not only this transition between Asian and Australasian species, but also numerous species unique to the surrounding area,[59] now termed "Wallacea".[58]

As a highly populous country part-way through a rapid industrialization process, Indonesia faces grave ecological issues, which are often given a lower priority due to high poverty levels and weak, under-resourced governance.[60] Issues include: large-scale deforestation (much of it illegal) and related wildfires causing heavy smog over parts of western Indonesia, Malaysia and Singapore; over-exploitation of marine resources; and environmental problems associated with rapid urbanization and economic development, such as air pollution, traffic congestion, garbage management, and reliable water and waste water services.[60] Habitat destruction threatens the survival of indigenous and endemic species, including 140 species of mammals identified by the World Conservation Union (IUCN) as threatened and fifteen identified as critically endangered, including the Sumatran Orangutan.[61]

Economy

Indonesian Gross Domestic Product (GDP) for 2005 was US$287 billion,[62] with per capita GDP (PPP) being US$4,458, ranking Indonesia 110th in the world.[1] The services sector is the economy's largest accounting for 45.3% of GDP (2005), followed by industry (40.7%) and agriculture (14.0%).[63] Agriculture, however, is the country's largest employer, employing 46.5% of the 95 million-strong workforce (NEEDS EDIT: When investigating the source cited for this statistic, it provides no evidence of the 46.5% number at all), followed by the services sector (41.7%) and industry (11.8%).[33] Major industries include petroleum and natural gas, textiles, apparel, and mining. Major agricultural products include palm oil, rice, tea, coffee, spices and rubber.

Indonesia's main export markets are Japan (22.3% of Indonesian exports in 2005), the United States (13.9%), China (9.1%), and Singapore (8.9%). The major suppliers of imports to Indonesia are Japan (18.0%), China (16.1%), and Singapore (12.8%). In 2005, Indonesia ran a trade surplus with export revenues of US$83.64 billion and import expenditure of US$62.02 billion. The country has extensive natural resources, including crude oil, natural gas, tin, copper, and gold. Indonesia's major imports include machinery and equipment, chemicals, fuels, and foodstuffs.[64]

Despite its immense natural resources and agricultural productivity, prosperity has often failed to be equitable. Following independence, the economy deteriorated drastically as a result of political instability, a young inexperienced government, and ill-disciplined economic nationalism. By the time of Sukarno's downfall in the mid-1960s, the economy was in chaos with 1,000% annual inflation, shrinking export revenues, crumbling infrastructure, factories operating at minimal capacity, and negligible investment, resulting in severe poverty and hunger.[65] The New Order administration brought a degree of discipline to economic policy that quickly brought inflation down, stabilized the currency, managed foreign debt, and attracted foreign aid and investment.[65]

Indonesia is Southeast Asia's only member of OPEC and the 1970s oil price rises provided an export revenue windfall and growth from 1968 to 1981 that averaged over 7%.[65] Growth slowed, however, to an average of 4.3% per annum between 1981 and 1988 due to declining oil prices, on which the Indonesian economy had become heavily dependant, and inefficiencies due to over-regulation. The late 1980s saw a range of economic reform measures including a managed devaluation of the Rupiah to improve export competitiveness, and de-regulation of the financial sector. Foreign investment flowed into Indonesia, particularly into a rapidly developing export-orientated manufacturing sector, and from 1989 to 1997, the Indonesian economy grew by an average of over 7%.[65] [66]

The East Asian financial crisis of 1997-98, however, hit Indonesia hard. Against the USD, the currency dropped from about Rp. 2,000 to Rp. 18,000 and the economy shrunk by a devastating 13.7%, causing much hardship.[66] The Rupiah has since stabilized at around Rp. 10,000 and there has been a slow but significant recovery. GDP growth exceeded 5% in both 2004 and 2005 and is forecasted to increase.[67][68] The patchy nature of the recovery has been exacerbated by political instability since 1998, perceptions of corruption at all levels of government and business, and a perceived slow pace of economic reform.[69] Real per capita income has reached pre-1997 crisis levels but annual inflation in 2006 is estimated at 17%.

Demographics

The national population from the 2000 national census is 206 million.[70] The country's Central Statistics Bureau and Statistics Indonesia quoted 222 million as the population for 2006.[71] 130 million people live on the island of Java, the world's most populous island.[72] Despite a considerably successful family planning program over the last four decades, the population is expected to grow to around 315 million in 2035 based on the current estimated annual growth rate of 1.25%.

Ethnic groups

Most Indonesians are ethnically Austronesian, particularly in central and western Indonesia, although much of eastern Indonesia is Melanesian. There are, however, around 300 distinct native ethnicities in Indonesia and 742 different languages and dialects.[73][74] Small but significant populations of ethnic Chinese, Indians and Arabs are concentrated mostly in urban areas. An almost universally shared sense of Indonesian nationhood overlays this vast diversity and steadfastly maintained regional identities, providing a largely harmonious society.

Indonesia, however, is not without social tensions with religious and ethnic differences triggering sometimes horrendous violence. The transmigration program contributed to the spread of people from highly populated Java and Madura to eastern Indonesia. Ethnic and religious differences between these immigrants and the local peoples have been blamed for numerous difficulties, sometimes culminating in bloody conflicts such as the massacre of hundreds of Madurese by a local Dayak community in West Kalimantan,[75][76] and conflicts in Maluku,[77] Central Sulawesi,[78] and parts of Papua and West Irian Jaya.

Chinese Indonesians are arguably the most influential ethnic minority in Indonesia. Although the Chinese make up only 2% of the population, the majority of the locally-owned businesses and wealth in the country is Chinese-controlled. This has caused considerable resentment[79][80] despite the fact that it is only a small proportion of Chinese that hold great wealth, and that a large middle class of prosperous, non-Chinese has developed. The riots in Jakarta in 1998, much of which was aimed at the Chinese, were expressions of these sentiments.[81][82]

Languages

The official national language, Indonesian (Indonesian: Bahasa Indonesia), is universally taught in schools and is spoken by nearly every Indonesian. It is the language of business, politics, national media, education and academia. Yet, in isolated areas – even on the major islands – it is not uncommon to find villagers who are not familiar with Indonesian.[83][84] It was originally a lingua franca for most of the region, including present-day Malaysia and is thus closely related to Malay. It was first promoted as a national language in 1928 by the Indonesian National Party (PNI), accepted by the Dutch as the de facto language for the colony, and then declared the official language after independence. Most Indonesians speak at least one of the several hundred local languages (bahasa daerah), often as their first language. Of these, Javanese is the most widely-spoken language, as it is the language of the largest ethnic group.[64] Papua on the other hand, has as many as five hundred or more indigenous Papuan or Austronesian languages in a region of just 2.7 million people.

Religion

Although the Indonesian constitution guarantees religious freedom for all citizens,[85] the Government officially only recognizes six religions, namely Islam, Protestantism, Catholicism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Confucianism.[86] Indonesia is the world's most populous Muslim-majority nation with almost 86% of Indonesians declared Muslim according to the 2000 census.[64] 11% of the population is Christian (of which roughly two-thirds are Protestant), 2% are Hindu, and 1% Buddhist.

Before the arrival of the Abrahamic faiths of Christianity and Islam, the popular belief systems in the region were thoroughly influenced by Indic religious philosophy through Hinduism and Buddhism. The influence of Hinduism and classical India remain defining traits of Indonesian culture; the Indian concept of the god-king still shapes Indonesian concepts of leadership and the use of Sanskrit in courtly literature and adaptations of Indian mythology such as the Ramayana and Mahabharata. The vast majority of Hindus are Balinese who, similar to abangan Muslims, follow a version of Hinduism fused with existing cultural and religious beliefs and markedly distinct from orthodox Hinduism.Template:Fact The Sumatra-based Sriwijaya kingdom of the seventh century AD was an early center of Buddhism in Indonesia. Most Buddhists in modern-day Indonesia, however, are ethnic Chinese.[87]

Islam was first brought to northern Sumatra by Arab traders in the thirteenth century and had become Indonesia's dominant religion by the fifteenth century.[88] Although Islam was once mainly practiced in Java and Sumatra, Indonesia-wide emigration has increased the number of Muslims living in Bali, Borneo, Sulawesi, Maluku, and Papua. Like other religions in Indonesia, Islam has blended with local traditional beliefs such as those practiced by the Abangan Muslims on Java[89] and with other belief systems in northern Sumatra and Kalimantan. Such syncretic practises draw on distinctly Indonesian customs and typically differ from more Orthodox Islam by favoring local customs over Islamic law. One notable difference includes a generally greater level of freedom and higher social status for women.[90] The majority of Indonesian Muslims are generally accepting of differing religious practices and interpretations within their own faith.[90] Although the form of worship may differ, Muslims in Indonesia are typically devout; many have made the pilgrimage to Mecca, for example. More Orthodox Muslims believing in a stricter adherence to Sharia make up a smaller but growing percentage of the population;Template:Fact the wearing of a jilbab, for example, is becoming more common.Template:Fact There is a small but outspoken hard-line Islamist presence in Indonesia, some of which seek to establish Indonesia as an Islamic state. Most Indonesian Muslims, however, are wary of these movements.

Catholicism was first brought to Indonesia by early Portuguese colonialists and missionaries, and the Protestant denominations are largely a result of Dutch Calvinist and Lutheran missionary efforts during its colonial time. Missionary efforts did not extend to Java or other predominantly Muslim areas. As with Islam and Hinduism, Christian beliefs in Indonesia are sometimes combined with animism and other traditional beliefs and cultural practices.

Culture and art forms

Indonesia has around three hundred ethnic groups, each with cultural differences that have shifted over the centuries. Modern-day Indonesian culture is a fusion of this diversity. Indonesia has also imported cultural aspects from Arabic, Chinese, Malay and European sources.

Traditional Javanese and Balinese dances, for example, contain aspects of Hindu culture and mythology as does the Javanese and Balinese wayang kulit ("shadow puppet") shows, depicting mythological events. Cloth such as batik, ikat and songket are created across Indonesia with different areas having different styles and specializations. The most dominant influences on Indonesian architecture have traditionally been Indian, however, Chinese, Arab, and, particularly from the 19th century, European architecture has had a significant influence. Pencak Silat is a unique martial art originating from the archipelago.

Derived from centuries of exchange with Chinese, European, Middle Eastern and Indian influences, Indonesia has developed its own distinctive cuisine, which varies across its regions.[91] Rice is the staple food of most Indonesian dishes and is served with several side dishes of meat and/or vegetables. In comparison to the infused flavors of Vietnamese and Thai food, flavors in Indonesia are kept relatively separate, simple and substantial.[92] Spices, notably chilli, and coconut milk are fundamental ingredients as is fish and chicken, although red meat tends to be expensive.

Indonesian music varies within cities and groups as people who live in the countryside would listen to a different kind of music than people in the city. Although rock was introduced to Indonesia by the Indonesian rock band God Bless (see Ian Antono),[93] native Indonesian music is still preserved. Examples of Indonesian traditional music are Gamelan and Keroncong. Dangdut is a hugely popular contemporary genre of pop music partly derived from Arabic, Indian, and Malay folk music. The Indonesian movie industry's popularity peaked in the 1980s and dominated cinemas in Indonesia,[94] although it fell significantly in the early 1990s.[95] As of 2000, however, the industry has improved gradually with a number of successful movies released.[94]

Media freedom in Indonesia increased considerably after the end of President Suharto's rule, during which the now-defunct Ministry of Information monitored and controlled domestic media and restricted foreign media.[96] The TV market includes ten national commercial networks and provincial networks that compete with public TVRI. Private radio stations carry their own news bulletins and foreign broadcasters can supply programs. Internet use is increasing; Bisnis Indonesia reported in 2004 that there were 10 million users.Template:Fact

See also

References

Bibliography and further reading

- History

- Anderson, Ben (1972). Java in a Time of Revolution: Occupation and Resistance, 1944-1946. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-0687-0.

- Beekman, E.M. (editor), Fugitive Dreams: An anthology of Dutch colonial literature, 2000 Periplus Editions Ltd, Hong Kong, ISBN 0870235753

- Drakeley, S: The History of Indonesia, Westport, Connecticut : Greenwood, 2005, 201 pages, ISBN 0-313-33114-6

- Friend, T Indonesian Destinies, Harvard University Press, 2003, hardcover, 544 pages, ISBN 0-674-01137-6

- Milton, G., Nathaniel’s Nutmeg: How one man's courage changed the course of history, 2000 Sceptre; 400 pages, ISBN 0-340-69676-1

- Raffles, T.S. The History of Java, Oxford Univ Pr (T) 1979 (originally published 1817), ISBN 0-19-580347-7

- Ricklefs, M.C, A History of Modern Indonesia 2002 Stanford University Press; 3rd ed, 512 pages, ISBN 0-8047-4479-3

- Politics and economics

- Luwarso, L.(editor), Jakarta Crackdown, 1997, Alliance of Independent Journalists, FORUM-ASIA, & ISAI, 318 pages.

- Schwarz, A. 1999, A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia's Search for Stability, Westview Press; 2nd edition (October 1999), ISBN 0-8133-3650-3

- Llyod G, Smith S, Indonesia Today, Lanham, Maryland : Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2001, 343 pages, ISBN 0-7425-1761-6

- Travel

- Wallace, A.R., The Malay Archipelago, 1869, 515 pages. (re-released paperback edition by Periplus Editions Ltd, 2000, ISBN 962-593-645-9)

- Society

- Magnis-Suseno, F., Javanese Ethics and World View: The Javanese idea of the good life, 1981 (translated from the German 1997), PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama, ISBN 979-605-406-X

- Pramoedya, A., Tales from Djakarta: caricatures of circumstances and their human beings, Equinox Publishing (Asia) PTE LTD, 2000 (first published 1963), Jakarta, ISBN 979-95898-1-9

- Koch, C., The Year of Living Dangerously (fiction), 1978 Michael Joseph Ltd, London

- Arts and culture

- Dawson, B., Gillow, J., The Traditional Architecture of Indonesia, 1994 Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, ISBN 0-500-34132-X

- Holt, Claire. Art in Indonesia: Continuities and Change . Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967

- Richter, A., Arts & Crafts of Indonesia, 1993 Thames and Hudson Ltd, London, 160 pages, ISBN 0-8118-0454-2

- Wijaya, M., Architecture of Bali: A source book of traditional and modern forms, 2002 Archipelago Press, Singapore, 224 pages, ISBN 981-4068-25-X

- Natural history

- Whitten, T., Whitten, T, Wild Indonesia: The wildlife & scenery of the Indonesian archipelago, 1992 New Holland Ltd, London, ISBN 1-85368-128-8

- The Ecology of Indonesia Series (7 volumes), 1996. Periplus Editions

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 International Monetary Fund (April 2006). Estimate World Economic Outlook Database. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ U.S Library of Congress (December 2004). Country Profile: Indonesia. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-09.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Tomascik, T; Mah, J.A., Nontji, A., Moosa, M.K. (1996). The Ecology of the Indonesian Seas - Part One. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd.. ISBN 962-593-078-7.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Template:Id icon Anshory, Irfan. Asal Usul Nama Indonesia, Pikiran Rakyat, 2004-08-16. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Earl, George S. W. (1850). "On The Leading Characteristics of the Papuan, Australian and Malay-Polynesian Nations". Journal of the Indian Archipelago and Eastern Asia (JIAEA): 119.

- ↑ Ibid, pp. 254, 277–278.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Jusuf M. van der Kroef (1951). "The Term Indonesia: Its Origin and Usage". Journal of the American Oriental Society 71 (3): 166–171.

- ↑ Pope (1988). "Recent advances in far eastern paleoanthropology". Annual Review of Anthropology 17: 43-77. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E., Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd, 309-312.

- ↑ Pope, G (August 15, 1983). "Evidence on the Age of the Asian Hominidae". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80 (16): 4,988-4992. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E., Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd, 309.

- ↑ de Vos, J.P.; P.Y. Sondaar, (9 December 1994). "Dating hominid sites in Indonesia". Science Magazine 266 (16): 4,988-4992. DOI:10.1126/science.7992059. Research Blogging. cited in Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E., Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd, 309.

- ↑ Peter Lewis (1982). "The next great empire". Futures 14 (1): 47-61.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Ricklefs, M.C. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan, p.24. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ↑ Gert Oostindie and Bert Paasman (1998). "Dutch Attitudes towards Colonial Empires, Indigenous Cultures, and Slaves". Eighteenth-Century Studies 31 (3): 349-355.

- ↑ Angus Maddison (1989). "Dutch Income in and from Indonesia 1700-1938". Modern Asian Studies 23 (4): 645-670.

- ↑ Pramoedya Ananta Toer. Sukarno, TIME, 23-30 August 1999. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ H. J. Van Mook (1949). "Indonesia". Royal Institute of International Affairs 25 (3): 274-285.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Charles Bidien (5 December 1945). "Independence the Issue". Far Eastern Survey 14 (24): 345-348.

- ↑ Indonesian War of Independence". Military. GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2006-12-11.

- ↑ John Roosa and Joseph Nevins (5 November 2005). "40 Years Later: The Mass Killings in Indonesia". Counterpunch. Retrieved on 2006-11-12.

- ↑ Robert Cribb (2002). "Unresolved Problems in the Indonesian Killings of 1965-1966". Asian Survey 42 (4): 550-563.

- ↑ John D. Legge (1968). "General Suharto's New Order". Royal Institute of International Affairs 44 (1): 40-47.

- ↑ Jonathan Pincus and Rizal Ramli (1998). "Indonesia: from showcase to basket case". Cambridge Journal of Economics 22 (6): 723-734. DOI:10.1093/cje/22.6.723. Research Blogging.

- ↑ President Suharto resigns, BBC, 21 May 1998. Retrieved on 2006-11-12.

- ↑ Burr, W.; Evans, M.L. (6 Dec 2001). Ford and Kissinger Gave Green Light to Indonesia's Invasion of East Timor, 1975: New Documents Detail Conversations with Suharto. National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 62. National Security Archive, The George Washington University, Washington, DC. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ↑ International Religious Freedom Report. Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights, and Labor. U.S. Department of State (2002-10-17). Retrieved on 2006-09-29.

- ↑ Robert W. Hefner (2000). "Religious Ironies in East Timor". Religion in the News 3 (1). Retrieved on 2006-12-12.

- ↑ Aceh rebels sign peace agreement, BBC, 15 August 2005. Retrieved on 2006-12-12.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 28.3 Susi Dwi Harijanti and Tim Lindsey (2006). "Indonesia: General elections test the amended Constitution and the new Constitutional Court". International Journal of Constitutional Law 4 (1): 138-150. DOI:10.1093/icon/moi055. Research Blogging.

- ↑ The Carter Center (2004). The Carter Center 2004 Indonesia Election Report. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ Andrew Ellis (16 July 2003). Countdown to 2004 Indonesia’s New General Election Law. USINDO Brief. USINDO. Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ _ (2002), The 4th Amendment of 1945 Indonesia Constitution, Chapter III – The Executive Power, Art. 7.

- ↑ Template:Id icon People's Consultative Assembly (MPR-RI). Ketetapan MPR-RI Nomor II/MPR/2000 tentang Perubahan Kedua Peraturan Tata Tertib Majelis Permusyawaratan Rakyat Republik Indonesia. Retrieved on 2006-11-07.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 Indonesia:Factsheet. Country Briefings. The Economist (3 Oct 2006). Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ People's Consultative Assembly (MPR-RI). Third Amendment to the 1945 Constitution of The Republic of Indonesia. Retrieved on 2006-12-13.

- ↑ World Bank (2006). Making the New Indonesia Work for the Poor - Overview. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-26.

- ↑ (Sep 14th 2006) "Poverty in Indonesia: Always with them". The Economist. Retrieved on 2006-12-26.

- ↑ Lateline TV Current Affairs. Sidney Jones on South East Asian conflicts, TV PROGRAM TRANSCRIPT, Interview with South East Asia director of the International Crisis Group, Australian Broadcasting Commission (ABC), 2006-04-20.

- ↑ International Crisis Group (2006-09-05). "Papua: Answer to Frequently Asked Questions". Update Briefing (No. 53): 1. Retrieved on 2006-09-17. [e]

- ↑ Wilson, Chris (2001-10-11). Indonesia and Transnational Terrorism. Foreign Affairs, Defense and Trade Group. Parliament of Australia. Retrieved on 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Commemoration of 3rd anniversary of bombings, AAP, The Age Newspaper, 2006-12-10. (in English)

- ↑ US Embassy, Jakarta (10 May 2005). Travel Warning: Indonesia. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-12-26.

- ↑ Huang, Reyko (2002-23-05). Priority Dilemmas: U.S. - Indonesia Military Relations in the Anti Terror War. Terrorism Project. Center for Defense Information.

- ↑ Peter Cave, Mark Colvin. (8 March 2006). Indonesian women rally against anti-pornography bill [TV Current Affairs]. Sydney: Lateline, Australian Broadcasting Corporation.

- ↑ Michelle Ann Miller (2004). "The Nanggroe Aceh Darussalam law: a serious response to Acehnese separatism?". Asian Ethnicity 5 (3): 333–351. DOI:10.1080/1463136042000259789. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Indonesia Law No. 5/1974 Concerning Basic Principles on Administration in the Region (translated version). The President of Republic of Indonesia (1974). Chapter VII Transitional Provisions, Art. 91.

- ↑ Elucidation on the Indonesia Law No. 22/1999 Regarding Regional Governance. People's Representative Council (1999). Chapter XIV Other Provisions, Art. 122.

- ↑ Dursin, Richel, Kafil Yamin. Another Fine Mess in Papua, Editorial, The Jakarta Post, 2004-11-18. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Central Intelligence Agency (2006-10-17). Rank Order Area. The World Factbook. US CIA, Washington, DC. Retrieved on 2006-11-03.

- ↑ Population density - Persons per km² 2006. CIA world factbook. Photius Coutsoukis (2006). Retrieved on 2006-10-04.

- ↑ Republic of Indonesia. Encarta. Microsoft (2006).

- ↑ Topinka, USGS/CVO, 2001; base map modified from CIA map, 1997; volcanoes from: Simkin & Siebert, 1994

- ↑ Whitten, T; Soeriaatmadja, R. E., Suraya A. A. (1996). The Ecology of Java and Bali. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd, 95-97.

- ↑ Indonesia. Global Virtual University. Globalis.

- ↑ Indonesia’s Natural Wealth: The Right of a Nation and Her People. Islam Online (2003-05-22). Retrieved on 2006-10-06.

- ↑ Whitten,, T.; Henderson, G., Mustafa, M. (1996). The Ecology of Sulawesi. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd.. ISBN 962-593-075-2.

- ↑ Monk,, K.A.; Fretes, Y., Reksodiharjo-Lilley, G. (1996). The Ecology of Nusa Tenggara and Maluku. Hong Kong: Periplus Editions Ltd.. ISBN 962-593-076-0.

- ↑ Indonesia. InterKnowledge Corp.. Retrieved on 2006-10-06.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Severin, Tim (1997). The Spice Island Voyage: In Search of Wallace. Great Britain: Abacus Travel. ISBN 0-349-11040-9.

- ↑ Wallace, A.R. (2000 (originally 1869)). The Malay Archipelago. Periplus Editions. ISBN 962-593-645-9. ,

- ↑ 60.0 60.1 Jason R. Miller (1997-01-30). Deforestation in Indonesia and the Orangutan Population. TED Case Studies.

- ↑ Massicot, Paul. Animal Info - Indonesia. Animal Info - Information on Endangered Mammals.

- ↑ Indonesia Data Profile. [1]. The World Bank.

- ↑ Indonesia at a Glance. Indonsia Development Indicators and Data. World Bank (13 August 2006).

- ↑ 64.0 64.1 64.2 Indonesia - The World Factbook https://www.cia.gov/cia/publications/factbook/geos/id.html Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "indoCIA" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ 65.0 65.1 65.2 65.3 Schwarz, Adam (1994). A Nation in Waiting: Indonesia in the 1990s. Sydney: Allen & Unwin, 52-57. ISBN 978-1-86373-665-0.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Indonesia: Country Brief. Indonesia:Key Development Data & Statistics. The World Bank (September 2006).

- ↑ IMF Executive Board Concludes 2006 Article IV Consultation and Fifth Post-Program Monitoring Discussions with Indonesia. Public Information Notice (PIN) No. 06/91. International Monetary Fund, Washington, DC (7 August 2006).

- ↑ Indonesia: Forecast. Country Briefings. The Economist (3 October 2006).

- ↑ Guerin, G. (23 May 2006). "Don't count on a Suharto accounting". Asia Tims Online. [e]

- ↑ Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau (30 June 2000). 2000 Population Statistics. Press release. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Indonesian Central Statistics Bureau (1 September 2006). Tingkat Kemiskinan di Indonesia Tahun 2005-2006 (in Indonesian). Press release. Retrieved on 2006-09-26.

- ↑ Calder, Joshua (3 May 2006). Most Populous Islands. World Island Information. Retrieved on 2006-09-26.

- ↑ An Overview of Indonesia. Living in Indonesia, A Site for Expatriates. Expat Web Site Association. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Merdekawaty, E. (2006-07-06). "Bahasa Indonesia" and languages of Indonesia. UNIBZ - Introduction to Linguistics. Free University of Bozen. Retrieved on 2006-07-17.

- ↑ Pudjiastuti, T. N. (2002). Migration & Conflict in Indonesia. International Union for the Scientific Study of Population (IUSSP), Paris. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Kalimantan The Conflict. Program on Humanitarian Policy and Conflict Research. Conflict Prevention Initiative, Harvard University. Retrieved on 2007-01-07.

- ↑ Ajawaila, J.W.; M.J. Papilaya, Tonny D. Pariela, F. Nahusona, G. Leasa, T. Soumokil, James Lalaun, W. R. Sihasale (1999). Proposal Pemecahan Masalah Kerusuhan di Ambon. {{{booktitle}}}, Ambon, Indonesia: Fica-Net. Retrieved on 2006-09-29.

- ↑ Kyoto University: Sulawesi Kaken Team & Center for Southeast Asian Studies Bugis Sailors

- ↑ Swasono, M. F. (1997). Indigenous Cultures in the Development of Indonesia. INTEGRATION OF ENDOGENOUS CULTURAL DIMENSION INTO DEVELOPMENT. Indira Gandhi National Centre for the Arts, New Delhi. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Long, S. (1998-04-09). The Overseas Chinese. Prospect Magazine. Retrieved on 2006-09-17.

- ↑ Ocorandi, M. (28 May 1998). An Analysis of the Implication of Suharto's resignation for Chinese Indonesians. Worldwide HuaRen Peace Mission. Retrieved on 2006-09-26.

- ↑ Template:Id icon Winarta, F. H. (August 2004). Bhinneka Tunggal Ika Belum Menjadi Kenyataan Menjelang HUT Kemerdekaan RI Ke-59. Komisi Hukum Nasional Republik Indonesia (National Law Commission, Republic of Indonesia), Jakarata.

- ↑ Crawford, Brian. South of the Philippines, East of Kalimantan, West of the Malukus. {{{booktitle}}}, Conservation Strategies. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Salazar, Noel B. (2006-04-06). An Anthropologist's Report from Yogyakarta, Indonesia. {{{booktitle}}}, Penn Museum Research.

- ↑ The 1945 Constitution of the Republic of Indonesia. US-ASEAN. Retrieved on 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Yang, Heriyanto (August 2005). "The History and Legal Position of Confucianism in Post Independence Indonesia". Religion 10 (1): 8. Retrieved on 2006-10-02.

- ↑ Indonesia - Buddhism. U.S. Library of Congress. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved on 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Indonesia - Islam. U.S. Library of Congress. Retrieved on 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Magnis-Suseno, F. 1981, Javanese Ethics and World-View: The Javanese Idea of the Good Life, PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama, Jakarta, 1997, pp.15-18, ISBN 979-605-406-X.

- ↑ 90.0 90.1 Fajrul Falaakh, Mohammad (2002-12-11). Islam in Pluralist Indonesia: Challenges Ahead. The Centre for Independent Studies. Retrieved on 2006-10-15.

- ↑ Witton, Patrick (2002). World Food: Indonesia. Melbourne: Lonely Planet. ISBN 1-74059-009-0.

- ↑ Brissendon, Rosemary (2003). South East Asian Food. Melbourne: Hardie Grant Books. ISBN 1-74066-013-7.

- ↑ Template:Id icon Diaz (editor) (2005). Ian Antono: Pelopor Gitar Hero Indonesia. Biography of Ian Antono. Gitaris.com.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 Kristianto, JB. Sepuluh Tahun Terakhir Perfilman Indonesia, Kompas, 2005-07-02. Retrieved on 2006-10-05. (in Indonesian)

- ↑ Template:Id icon Kondisi Perfilman di Indonesia (The State of The Film Industry in Indonesia). Panton. Retrieved on 2006-10-05.

- ↑ Shannon L., Smith; Llyod Grayson J. (2001). Indonesia Today: Challenges of History. Melbourne, Australia: Singapore : Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 0-7425-1761-6.

External links

- Government

- Official site

- Antara - National News Agency

- Bank Indonesia - Indonesian Central Bank

- Department of Foreign Affairs of the Republic of Indonesia

- Statistics Center

- Other