Iraq War, major combat phase

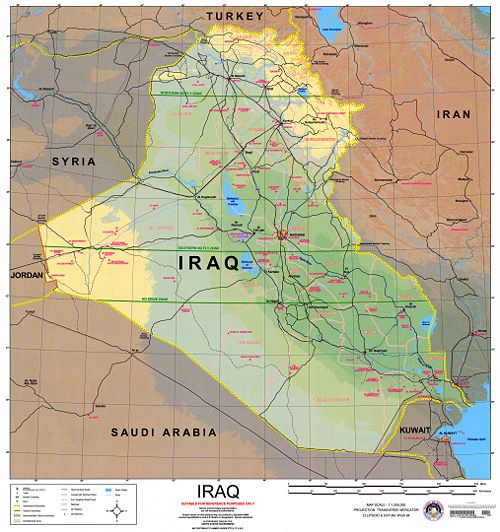

After a buildup by special operations forces and an intensification of air attacks under the Operation NORTHERN WATCH and Operation SOUTHERN WATCH "no fly" programs, major ground forces began to move into Iraq on March 20, 2003.

As with any war, no plan survives contact with the enemy. Both sides did consider Baghdad the key center of gravity, but both made incorrect assumptions about the enemy's plans. The U.S. was still sensitive over the casualties taken by a too-light raid in Operation GOTHIC SERPENT in Mogadishu, Somalia. As a result, the initial concept of operations was to surround Baghdad with tanks, while airborne and air assault infantry cleared it block-by-block. [1]

The U.S. also expected the more determined Iraqi forces, such as the Special Republican Guard and the Saddam Fedayeen, to stay in the cities and fight from cover. Before the invasion, the Fedayeen were seen as Uday Hussein's personal paramilitary force, founded in the mid-1990s. They had become known in 2000 and 2001, beheading dissenting women in the streets claiming they were prostitutes. "It was a very new phenomenon, the first time women in Iraq have been beheaded in public," Muhannad Eshaiker of the California-based Iraqi Forum for Democracy told ABC. [2] They had not been expected to be a force in battle. It was clear that the fedayeen had minimal military training. They seemed unaware of the lethality of the U.S. armored vehicles, and aggressively but haphazardly attacked them. [3] Senior Iraqi Army officers seemed to believe their own propaganda and assume that the war would go well, and there would never be tanks in Baghdad. It was only Special Republican Guard, Saddam Fedayeen, and unexpected Syrian mercenaries that seemed to understand the reality.[4] In an interview after the end of high-intensity combat, MG Buford Blount, commander of the 3rd Infantry Division, said "...there were many, I think, Syrian and other countries that had sent personnel; the countries didn't, I think individuals came over on their own that were recruited and paid for by the Ba'ath Party to come over and fight the Americans. We dealt with those individuals there for a two- or three-day period, had a lot of contact with them, but have not seen a reoccurrence of that at this point."[5]

There was great U.S. concern that the Iraqis would use chemical weapons once their forces passed some "red line" on the approach to Baghdad. Franks had a communications intercept that translated "Blood. Blood. Blood." This, along with the discovery of chemical protective equipment, put him on edge.

The chemical warfare did not materialize, but an unexpected surprise was that the Fedayeen and mercenaries jeopardized the supply lines to the advancing spearheads. To make matters worse, these irregular forces attacked with civilian vehicles, in civilian clothes, and from civilian sites. This unquestionably led to civilian casualties. It also forced the U.S. to assign forces that had been planned to hold ground or take cities, such as the 82nd Airborne Division and 101st Airborne Division, to shift some of their effort to road security.

Major units

Ground combat began with two corps formations, the Army's V Corps under LTG William "Scott" Wallace and the 1st Marine Expeditionary Force (including British units) under LTG James Conway. At the start, the V Corps was primarily the 3rd Infantry Division with supporting forces, but was steadily reinforced with additional divisions, such as the 82nd and 101st. The 4th ID did not deploy until large-scale combat was almost over.

The regular ground forces were under Coalition Land Forces Component commander LTG David McKiernan. Substantial special operations forces, both overt and covert, operated in coordination, but under a different component commander.

Northern Iraq and Turkey

It had been hoped that Turkey would allow the 4th ID to attack across Iraq's northern border. Even after the initial Turkish rejection, it was kept on ships with the intent of suggesting to Saddam that it might get permission. Zalmay Khalizad, who had been the senior National Security Council staffer for Iraq was in Ankara in March 2003, still trying to arrange this.

Moves of opportunity

The "RUNNING START" began with near-simultaneous air and ground attacks. The original plan had been to conduct limited air strikes against border operation posts on March 19, along with infiltration, under air cover, of Special Operations Forces from the military and CIA, the latter designated the Southern Iraq Liaison Element. Full-strength bombing was to begin on March 21.

When communications intelligence on March 19 indicated that Saddam might be at a location called Dora Farms, a contingency air operation went began on the 20th.[6] Times were tight; the ultimatum to Saddam expired at 4 AM local time; the F-117 aircraft had to be out of the area before dawn at approxiately 5:30. They took off at 3:30.[7] Cruise missiles hit aboveground targets at Dora Farms five minutes after the F-117's had dropped ground-penetrating bombs. Saddam, however, was not at the site.

Special operations forces were already operating in Iraq. Special operations forces (SOF) also moved into action, seizing oil and gas platforms in the south. SOF in the west positioned themselves to strike at airfields, missile sites, and suspected WMD facilities. In the north, they worked with the Kurdish resistance to pin the Iraqi forces in that area.

Iraq countered with surface-to-surface missiles fired at U.S. headquarters on the afternoon of the 20th. They were shot down. [8]

Special operations probes

On the 19th, a Delta Force squadron scouted several potential WMD sites, and found no threat. [9]

Shaping the battlefield

The main operation of the "shaping the battlefield" phase began with breaking through a 10km wide Iraqi defensive line, on March 20. This phase lasted until March 23.

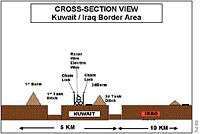

The major units positioned themselves for penetrating the Iraqi border. This was called crossing the "berm", although the berms (plural) were earthen walls that made up part of the physical barriers at the border. Note that a substantial amount of the barrier was in Kuwait. According to the U.S. Army history, much of the actual breaching was done by Kuwaitis contractors, who considered it an honor, but could also disguise some of the preparation as routine maintenance. [10] Another account, however, said that the Kuwaitis were reluctant to plow over the defenses they had built, including an electrified fence; they arranged, in discussions with McKiernan's staff, to have contrators take down sections of their barriers.[11]

Breaching the berms proper was separate from creating lanes through the defensive line, which was done by combined arms units, such as TF3-15, based on two mechanized infantry companies (Alpha and Bravo, 3rd Battalion, 15th Infantry), one attached tank company (Bravo Company, 4-64 Armor), one engineer company (Alpha Company, 10th EN), and a psychological operations. It split into organized into two elements, one of armored fighting vehicles and one of wheeled vehicles.

The first combat by conventional forces, took at 3:57 PM local time, but south of the Iraqi border, between Iraqi vehicles and U.S. Marine Corps LAV-25 reconnaissance vehicles from the 3rd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion. Marines began the actual attacks with artillery fire in the late afternoon, preceding the border crossing by the 1st Marine Division under I Marine Expeditionary Force under then-LTG James Conway. The Division cooperated closely with 1 Armored Division (U.K.) and the Army's 3d Infantry Division (U.S.)[12] The Army units were under V Corps.

Lane-clearing teams were ready on the 20th, waiting for movement on the 22nd. While they waited, they were in chemical protective clothing, donning masks when Iraqi surface-to-surface missiles were fired.

Lead Marine units first crossed the Kuwait-Iraq border and began an intensive attack on Safwan Hill, in Iraq just north of the border. [13]

Oil fields

The first Army unit to enter Iraq was the 3rd Squadron, 7th Cavalry Regiment, part of the 3rd Infantry division, at approximately 1 AM local time on the 20th according to CNN, although Defense Department reports suggest the movement was four hours later. [12] In either case, the attack time was accelerated due to concern over the Iraqis' damaging oil facilities.

When Marines seized the Crown Jewel pumping station in Zubayr, 10 miles southwest of Basra, they were concerned that machinery had been damaged, but the Iraqi managers said this was the normal state of the equipment; the Iraqi petroleum industry needed rehabilitation. [14]

As the Marines moved into the Rumaylah oil field, British forces took control of the Faw Peninsula oil facilities, as well as the port of Umm Qasr. U.S. Navy SEALs captured some of the offshore facilities. A U.S. Marine helicopter crashed, killing Marines from both countries. [15]

Attacks on Talil Airfield and on Basra

On the 22nd, the 3rd Infantry division drove troughly 150 miles into Iraq, halfway to Baghdad, to the Tal Airfield. The 3rd Brigate attacked the airfield with the 1/30 Infantry protecting the flanks and the 1/15 attacking the Iraqi 11th Infantry division in defense. The 3rd Brigade captured the Talil airfield after its artillery began shelling Iraqi military emplacements there. While the 1-30th Infantry protected its flanks preventing intervention by forces in Nasiriyah, the 1-15th Infantry Regiment assaulted the airfield inflicting serious losses on Iraq's 11th Infantry Division, which was defending the location. The 3rd ID used a bounding overwatch, where one brigade at a time would attack, covered by another. [16] The 11th Infantry later surrendered resulting in the capture of some 300 prisoners.

In parallel, 1st Marine Division drove toward Bastra, destroying 10 dug-in T-55 tanks with hand-held and HMWWV-launched antitank missiles.

Eight miles south of Basra at a turnoff to Zubair, the 3rd Battalion, 7th Marines Regiment took over an abandoned Iraqi command and control facility and used it as a field headquarters. The marines left this position later in the day as forces began heading closer to Basra.

Resistance by irregulars

On the 23rd, the advancing forces ran into unexpected resistance from Fedayeen irregulars, which did not present a threat to the armored fighting vehicles, but caused a problem for supply lines. They also faked surrenders and used human shields. [17] Part of the Army 509th Maintenance Company, having taken a wrong turn and driven into the city of An Nasiriyah, were ambushed and prisoners, including Jessica Lynch, taken. [18]

The first large thrust

After breaching the berm, it would take at least two movements to reach Baghdad; there would need to be regrouping on the 400 km drive to the north from Kuwait. The contingency of sudden collapse of the Iraqi leadership was always considered as a contingency.

The "darkest day"

Some of the hardest fighting came on the night of the 23rd and 24th. One component was an unsuccessful deep strike by AH-64 Apache helicopters at the Battle of Karbala. [19] This was a pure air attack; the 101st decided to defer its originally planned near-simultaneous attack, on the 14th Brigade of the Medina Division, until the 28th.[20]

U.S. Political factors

LTG Wallace had given an interview to U.S. newspapers on the 27th, in which he suggested the war might take longer than planned, due to the paramilitaries and the weather. [21] According to Gordon and Trainor, Rumsfeld felt this was disloyal, and raised it to Franks, who expressed to McKiernan that he was considering relieving Wallace. Franks had unfavorably compared the aggressiveness of V Corps to the Special Operations forces.[22] Rumsfeld, however, denied he had read the interview, but warned Syria and Iran to stay out of the irregular fighting. [23]

In his autobiography, Franks said he was told of the incident by his press officer, COL Jim Wilkinson, on the morning of the 27th, who said "a couple of reporters ambushed Scott Wallace when he popped in to visit General Petraeus at the command post." Franks said he described it as basically accurate from the perspective of a corps commander, but definitely pessimistic. Wilkinson described it as "A friggin' disaster, General. The takeaway is that we're bogged down and didn't plan this operation worth a damn." When Franks said this was untrue, Wilkinson said "perception is reality in the media. My phone has been ringing off the hook for the last hour. Everyone wants to interview you about Wallace's comments." Franks told Wilkinson to stay with operational truth, and he would talk to McKiernan. When Franks talked to McKiernan, the latter said he had warned Wallace, and Franks said "that's good enough for me. Scott is a hell of a commander. Tell him I love him and trust him."[24]

Haditha Dam

The Haditha Dam is a water and hydroelectric power facility 125 miles northwest of Karbala. CENTCOM determined that Iraqi destruction of the dam, could have an immediate impact on the fight by causing floods, and subsequent catastrophic effects on infrastructure when stored water would not be available during the summer. The assessment came from the Army Engineer Research and Development Center's (ERDC) TeleEngineering Operations Center in Vicksburg, Miss. [25] A decision was made to use Rangers to seize it; Rangers had been held in reserve for seizing WMD caches or Baghdad International Airport. JSOC had made seizing the airport, in the event of a regime collapse, a major priority; airport seizure is a classic Ranger mission, and was especially significant to MG Dailey, an aviator. The 3rd Infantry Division, however, was confident it could take the airport more reliably than JSOC. LTC Blaber, the Delta Force squadron commander, had been told the dam was a high priority, possibly as a WMD storage site.

Isakoff and Corn suggest that the dam mission was an ad hoc assignment to the Rangers, who did not have a clear mission. Rangers made a parachute jump and seized the H-1 airfield on March 27. A tank company was then airlifted to them, and the combined force, the first time armor had been put under special operations, seized the dam on April 1. Once they had it, however, they discovered it was poorly maintained. An engineer, with limited dam experience, was flown in two days later and helped maintain it, along with the Iraqi staff.[26]

The Pause

As opposed to the situation in the Afghanistan War (2001-), there was no meaningful Iraqi resistance that could be assisted by Special Operations forces, at least in Southern Iraq. The Kurds in the north were quite another matter.

Instead, the Iraqi irregular Fedayeen were a real threat to the rear areas of the advancing forces. By the 28th, Conway described the main Iraqi military as in a deliberate defense. complemented by the Fedayeen.[27] Wallace, McKiernan and Conway were all concerned with protecting their rear areas; McKiernan had released the the 82nd Airborne Division and to V Corps, for rear security, on the 26th. [28]McKiernan said that before moving north, he wanted the Republican Guard reduced by 50%, and the 101st Airborne Division committed to rear security. [29]

New raid on Karbala

Having learned lessons from the first deep helicopter raid on Karbala, an attack combining more types of force taken against the 14th Brigade of the Medina Division on March 28. Rather than Apaches alone, and in a single mass, the attack helicopter route was prepared. First, artillery and fixed-wing fighter-bombers hit the Iraqi forward areas. The close air support (CAS) aircraft would loiter in the area, and the helicopter force would include an airborne forward air controller (AFAC). Four minutes before the helicopters were to strike, MGM-140 ATACMS surface-to-surface missiles would strike air defenses.

The Apaches split into two battalion-sized elements. As no plan survives contact with the enemy, the element planned as the main attack force found few targets, while the feint element discovered the main enemy concentration.

Both forces flew differently than on the 23rd, based on the "lesson learned" about ground fire from civilian vehicles. In each formation, one helicopter provided security to the rear and two to the sides, while the rest looked for main targets. They destroyed five pickup trucks armed with heavy machine guns.

Airdrop on Bashur

On March 26, 2003, the 173rd Airborne Brigade made the largest combat paratroop operation since the Second World War. Landing in the Bashur Drop zone, they effectively opened a northern front, diverting Iraqi forces from the main ground assault from the south.[30]

It is not clear, however, that the Iraqis took this as more than a diversion, since they were reasonably certain that Turkey would not permit a large ground force to cross its border into Iraq. Supplying the 173rd was also a major challenge.

The 173rd did not see combat until April 10, when it moved into Kirkuk, after special operations forces had driven out the Republican Guard and Regular Army. It did play an important role in stability operations in Kirkuk and other Kurdish areas.

March 31 commanders' conference

Franks held a meeting at McKiernan's headquarters on the 31st. Behind closed doors, with senior officer, he was highly critical, and his attitude offended some of the deputies, especially Albert Whitley, the senior British officer, who felt Franks was unconcerned about casualties. Franks had said that only the British and the Special Operations Forces had been fighting, and was especially angry with the 3rd ID. He wanted a clear plan on how to use the 4th ID when it arrived.

He also said that McKiernan had not taken some objectives that he should have taken, starting with Baghdad International Airport. He wanted the Iraqi 6th and 10th Divisions engaged, which the Marines and McKiernan felt were out of the fight.[31]

Afterwards, McKiernan went to Whitley, a comrade from the Balkans, and told him "this conversation never happened."

An Najaf

Karbala would still have to be taken on the ground, and An Najaf controls the approach to it. The city is along the Euphrates River, with several bridges across it. Highways 9 and 28 parallel the river; Highway 9 runs through An Najaf. On the 31st, as the heavy 3rd Infantry Division regrouped to hit the Republican Guard, the 101st Airborne Division prepared to contain An Najaf. Within hours of attacking, the 3rd Battalion, 1st Brigade of the division had secured the airport for humanitarian operations and military logistics. The 1st Battalion took an infantry training center.

An Najaf presented problems beyond the pure military, as it holds one of the holiest shrines in Islam, the Tomb of Ali, son-in-law of the Prophet and founder of Shi'a Islam. When forces from the 2nd Battalion, 1st Brigade of the 101st approached it, they were fired on by Iraqis inside. The battalion commander, aware of the cultural sensitivity, surrounded the shrine and used snipers against those inside, but would not send troops into it. [32]

The overall operational concept was to contain An Najaf from the southwest and northwest and isolate from the north and east. This would prevent enemy paramilitary forces from interdicting logistics operations in Objective RAMS and position the division to prevent other enemy forces from reinforcing An Najaf.

To do this, 3rd Infantry Division would capture the two bridges on the north and south sides, and then put blocking forces on the east and west. 1st Brigade Combat Team would take the northern bridge at Al Kifl. Due to a shortage of uncommitted troops, the brigade air defense battery, in M6 LINEBACKER armored fighting vehicles, a Bradley derivative, was reinforced with scouts and forward observers, and directed to rush the bridge. If they were lucky, they would take it; they were backed by a tank-infantry reaction force. It was needed.

Five Simultaneous Attacks

The Karbala Gap, between Bahr al-Milh Lake (Buhayrat ar Razazah) and the city of Karbala, was the best avenue for a major assault on Baghdad. It is a narrow corridor with little room to maneuver, only about one-and-a-half kilometers wide with an escarpment that had to be crossed. By using this route, V Corps avoided Iraqi forces on the east side of the Euphrates River.

A first proposal to keep up momentum came from Blount, who proposed having Perkins' 2nd Brigade Combat Team feint at Hindiyah on the Euphrates River, driving to but not across the bridge. This, Blount thought, would provoke the Iraqis to fire artillery, which could be detected by counterbattery radar and destroyed. Wallace thught this was a good idea, and expanded it to include four more attacks.[33]

Other approaches crossed rivers, or at least went into soft, irrigated land that was poor terrain for tanks. Unfortunately, the attackers knew this, and had good fields of fire to the defenders and limited maneuver space and few exits for the attackers. It would be necessary to confuse the defenders. Deceptive feints were the first actions, such as that of 3-7 Cavalry on March 30.[34]

These movements successfully convinced the Iraqis that the attacks were coming across the Euphrates and up Highway 8, and they repositioned to meet that threat. In particular, Republican Guard forces, two brigades of the Medina Division, moved onto the highway in daylight hours. They also unmasked their artillery in built-up areas. Brigades from the Republican Guard Hammurabi and Nebuchadnezzar Divisions spotted further along Highway 8, to present a defense in depth. These movements gave significant targeting information to fighter-bombers under the Fighter-bombers directed by the 4th Air Support Operations Group (ASOG).

In a joint Air Force-Army operation, V Corps concentrated its unmanned aerial vehicles into the area to spot targets, against which ASOG directed airstrikes. Both from the UAVs and the fighters, immediate battle damage assessment was available that was not available from artillery, or from air forces directed at a level more indeoendent of the ground units. [35]

Shows of force

Before attempting to take and hold Baghdad, several peripheral or demonstration operations were used as much for psychological as kinetic attack. These also gave commanders a better understanding of Iraqi operational style, using new networked techniques such as unmanned aerial vehicle video and Blue Force Tracker unit position awareness. At the division level, "The V Corps common operational picture was 90% BFT. BFT was one of two resounding successes for OIF because commanders down to Brigade level were able to track combat maneuver units in near real time." 3rd Infantry Division said “The single most successful C2 system fielded for OIF was the FBCB2-BFT system…BFT gave commanders situational understanding that was unprecedented in any other conflict in history”[36]

Baghdad airport

A major objective had always been Baghdad International Airport. While the V Corps staff had thought the best approach to seizing it was by air assault by the 101st Airborne Division, while MG Dailey of JSOC saw it as a mission for his force, MG Buford C. "Buff" Blount III, commanding 3rd Infantry Division, felt confident he could take it. Blue Force Tracker also gave him confidence of staying aware of the situation and not becoming overextended.

He directed the 1st Brigade, under COL William Grimsley, to move against it. 3-69 Armor was the lead battalion, under LTC David Perkins, covered by extremely heavy artillery fire. The artillery was thought to have broken the morale of the Special Republican Guard defenders. [37]

The first Coalition aircraft to use Baghdad International landed there on April 8. It remained a hazardous airfield, but it was usable by military pilots with appropriate tactical air traffic control.

First Thunder Run

COL David Perkins, commanding the Second Brigade, was concerned about a lack of momentum, and proposed a raid to MG Blount. [38] Blount agreed, and ordered Perkins to make a "Thunder Run" raid into the city proper on April 4. The raid used a battalion task force (TF 1-64) built around "Rogue Battalion", or the "Desert Rogues" of 1st Battalion, 64th Armored Regiment, under LTC Eric Schwartz.

It was a day that saw a surreal contrast between the announcements of the Iraqi information minister, Mohammed Saeed al-Sahaf, known as "Baghdad Bob", and the U.S. probes into Baghdad, called "Thunder Runs". Objectively, they were high-speed reconnaissance in force by U.S. armored columns, to which Franks gave that name after similar operations during the Vietnam War: "a unit of armor and mechanized infantry moving at high speed through a built-up area such as a city. The purpose was either to catch the enemy off guard or overwhelm him with force."[39] A correspondent, perhaps tastelessly but not completely inaccurately, referred to them as "the longest drive-by shooting in history". [40] As video, from an embedded reporter in the 1-64 Armor task force and from an UAV flying above, showed armored vehicles on the highway, driving up to Baghdad International Airport from a different route than that taken by 3-69 Armor, the information minister claimed

They are not near Baghdad. But if they are, we shall slaughter them

It must be understood that this was a short operation, lasting 2.5 hours, by a battalion task force. U.S. casualties were light but casualties, largely among ill-trained irregulars, were estimated as between 800 and 1000. Lessons were learned, including the capabilities and limitations of UAV and Blue Force Tracker for keeping higher headquarters informed. While they had moved down a seemingly high-speed highway, they learned overpasses were key chokepoints.[41]

Second Thunder Run

Blount, on April 5, reviewed the result of the first Thunder Run, and considered if another one would contribute to his goal of keeping pressure on the Iraqis, while major troop movements were being prepared. He expected reinforcement of Highway 8 and more digging in by the Iraqis, and thought that one, or multiple, Thunder Runs would be good preparation for the expected eventual siege of Baghdad.

Overall division operations had taken control of the intersection of Highways 1 and 8, which controlled access both to the airport, and to the city, 18 km north. A new run would start from there, and also use all of the Second Brigade rather than a battalion task force. [42] Blount said that Wallace told him "Don't go to stay. We are not ready to go to the palace yet." Blount said "I am sure that the division told the brigade just to go to the intersections and seize them. I always thought Perkins understood to stop at the intersections."[43]

According to Gordon and Trainor, Perkins did not receive the message that he was not to go downtown; he thought the controveray was whether he could stay overnight. He had, much as Blount had minimally described Thunder Run I to Wallace minimized how ambitious his plan was. [44] According to Zucchino, at the brigade level, Perkins had a more ambitious, information-centric goal than division and corps, which saw the raid as another in-and-out operations. [41] After LTC Eric Wesley, his executive officer, passed on Sahaf's new claims that "today, we butchered the force present at the airport", and, since the BBC had said its reporters had seen no tanks, gave credence to the Iraqi claims. Perkins told Wesley, "you know, this just changed from a tactical war to an information war. We need to go in and stay." The staff came up with a list of "key nodes" to seize and hold, the possession of which would be the equivalent of a coup d'etat — the essential pieces of government would be under the plotters' control. In Baghdad, most of these facilities, such as the presidential residence , television broadcasting, Ministry of Information, Ba'ath Pary headquarters, executive residences, the security headquarters, etc., were in a walled palace complex barred to the average Iraqi. The complex was als in open terrain with broad streets ideal for tanks. The Rogue battalion, already familiar with the roads, would take the area outside the palace complex, while the Tusker battalion, 4/64 Armor, organized as TF 4-64, would take the interior. 3/15 Infantry, the brigade's mechanized infantry unit ("China Battalion") under then LTC-Stephen Twitty, would keep the supply lines to the armored battalions open. [45]

TF China would hold a series of east-west road junctions north of Objective Saints along Highway 8, and to secure Objective Saints itself. To do this, it would leave company-sized combined arms teams at each of three major road intersections along the highway into Baghdad, designated CURLEY, LARRY and MOE. As opposed to the April 5 operation, the Iraqis were making serious attempts to block the highway with all resources, including construction equipment. Twitty created a company-sized force for each of the trhee objectives. [46] Twitty's operations center traveled with Team ZAN, which was to take CURLEY, the first objective, but Twitty himself was at LARRY in the middle, so he could stay in radio range of all three teams. Several Special Rorces personnel asked to go with ZAN, to make contact with Iraqis and perhaps talk them out of fighting. ZAN, under CPT Harry "Zan" Hornbuckle, ran into intense fight at CURLEY. Twitty called Perkins and told him to send the reserve, an infantry platoon that had been guarding the intersection of Highways 1 and 8. This very much concerned Perkins, who knew that the armored teams desperately needed the rearm-and-refit (R2) convoy that was to come over the route Twitty was to clear. [47] The reinforcing company turned the tide at CURLEY, but it was a near-run thing; the situation was sufficiently desperate that the chaplain, a former infantryman, had armed himself to protect the wounded.

2-7 Infantry, relieving CURLEY, had Ted Koppel of ABC News with them, as well as a Special Forces and CIA detachment. While the CIA people had intended to facilitate a surrender, it was too dangerous; Koppel was not going downtown. At LARRY, Twitty thought the enemy were on drugs, so desperate was their fighting.[48] While it had been expected the enemy would be Special Republican Guard, they turned out to be Syrian mercenaries at CURLEY. The Special Republican Guard, however, thickened closer to the city center; it was a mixture at LARRY and mosly SRG at MOE.[49]

Perkins and the brigade combat team headquarters moved with TF 1-64. At approximately 10 AM on the 7th, the brigade operations center was hit by an Iraqi surface-to-surface missile, killing five (including two embedded journalists), wounding dozens, and destroying much key equipment.

The second "Thunder Run", on April 7, stopped on the Presidential Palace grounds. Baghdad, however, was still contested.

Consolidating attacks on Baghdad

When the ASOG air attacks came to a close, the Marines went after Iraqi holdouts, moving up Highway 17 to Afak and Fajr. MG Jim Mattis, commanding the 1st Marine Division, had planned to attack Baghdad from the northeast, isolating the northern section, and then raiding in and out of the city. On April 6, Mattis gave assignments:

- Regimental Combat Team 5 (RCT-5), under COL Joe Dunford, would make the main attack, crossing the Diyala River from the northeast

- RCT-7, under COL Steve Hummer would cross the Diyala from the south, and attack the Al-Rasheed military base

On th 5th, a UAV showed the Diyala bridges had not been destroyed, and Mattis considered seizing them while his forces were still assembling. He decided to wait. By the 6th, however, the bridges were unusuable, and there were no bridges where RCT-5 wanted to attack. The marine engineer bridge battaliog commander thought, at first, he could cross in six hours, but he found, on reconnaissance, there was a good reason there were no Iraqi bridges: the soil was unsuitable to anchor a bridge of any size. LTC Niel Nelson, the bridge battalio commander, suggested that the main attack come from the east, which would go through Saddam City, a Shiite area that might be more anti-Saddam. It would also make it easier for them to swing north to Kirkuk, which was a contingency they had been given if Baghdad was under control. Mattis decided this was feasible. [50]

There had been enough delay that the Iraqis became aware of impending Marine attack in the east, and they met resistance. To their relief, Marine command had decided that if the Iraqis had not used chemical weapons while the Marines were concentrated on Highway 6, waiting for a bridge; the hot and cumbersome protective suits came off. They crossed with improvised bridges, and also, in the best Marine tradition and to the amazement of the Iraqis, used their amphibious vehicles for a secondary crossing of the Diyala. Meanwhile, Marine bridging engineers fixed the bridges in the north and were crossing into the city.

As the Marines moved into the southeast, the Iraqi Information Minister was still insisting there were no U.S. troops in Baghdad. [51]

Deconfliction

With more and more friendly troops in Baghdad, and communications intelligence reports that actual Iraqi military commanders, if not the Information Minister, were in panic, there was much concern to avoid "blue-on-blue" casualties in the ever-smaller battlespace.

Perkins had been given firm orders to stay on his side of the Euphrates, staying out of the Marine side, although he could order air and artillery strikes on the other side. The Iraqis did not have the same restriction, and were counterattacking across them. While MG Blount approved Perkins' request to destroy at least one bridge the Iraqis were using, LTG McKiernan refused it, on the grounds of avoiding too much damage to a city the US would then have to run.

During this time, there was an incident of fratricide on reporters at the Palestine Hotel.

Allyn's brigade was now moving into the city from the west, principally blocking bridges and inerceptions. On April 3, he had an engagement with Iraqi tanks, proving American intelligence could not find all enemy armor, but that US armor was more effective than Iraqi; Ferrell's 3-7 Cavalry destroyed 20 tanks. Still, Allyn's command post, with the supply trucks, took a fatality.

Refocusing

Franks first visited the troops in Iraq on the 7th. At the Marine field headquarters, he had told the generals "to hold hands and say a prayer thanking God for the looming victory." The idea of in-and-out raids had been overtaken by events. The new plan,, defined on April 9, had:[52]

- Mattis and the Marines attacking from the West, taking the Directorate for General Security, Ministry of Intelligence Ministry for Oil, Air Force Headquarters, and the Saddam Fedayeen control center.

- The Army would attack from the west

On April 9, the Marines helped Iraqis make one memorable scene, pulling down a statue of Saddam. CPL Edward Chin first put a US flag on the head, but Franks, McKiernan, and Conway quickly had it replaced by an Iraqi flag.

Also on the 9th, Saddam and his household evacuated Baghdad, moving to the west under fire, and into Anbar Province. By the 11th, he and his sons separated; Qusay and Uday attempted to seek refuge in Syria but were turned away. Saddam stayed in the western town of Hit.

After Baghdad

McKiernan now needed to get the Kirkuk oilfields under control, and take Tikrit, Saddam's home base. He was concerned about the limited Special Forces capability in the north, and wanted US troops up to the Turkish border — but did not have the troops to do it. JSOC TF 20 and the 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment would try to cover the Turkish and Iranian borders, altough McKiernan hoped for foreign assistance. The situation was becoming more complex; the Turks were complaining to Franks that the Kurds were harassing the Turkomans. Franks brushed this aside, still angry at the Turkish refusal to allow 4ID to cross into Iraq.

Kirkuk

Kirkuk, however, is indeed a complex issue among the Turks, Turkomen, and Kurds. The Turkomen consider it their traditional capital while the Kurds believe it should be part of Kurdistan. [53]

In Kirkuk, the Iraqi police had faded away, and the problem was with Kurdish rioting. Jalal Talabani called LTG Pete Osman, who headed a liaison organization called the Military Coordination and Liaison Command.

When Talabani wanted to send peshmerga to control the situation, Osman demurred, trying to keep the politically sensitive situation calm, especially with the Turks. Failing to stop Talibani's forces, he asked for help from the 173rd Airborne Brigade, which was under JSOTF-N control. Eventually, they began to patrol the city.There was significant looting, although the oilfields were untouched. Time's reporter also mentioned complaints by Turkomen against Kurgs. [54] Colin Powell had contacted the Turkish foreign minister and reassured him the peshmerga were leaving, and allowed Turkish observers. By April 9, the Kirkut oilfields were under control.

Tikrit

The Tikrit area, 175 km north of Baghdad, offered little resistance, although it had been the scene of a fight with Delta Force's Team Tank when they left Haditha Dam in early April. They did, however, rescue American POWs in Samarra. US troops, however, did not go into the center of the city.

Delta set up a base 13 miles to the west of Tikrit, and began raiding it. LTC Blaber, commanding Team Tank, refused some of MG Dailey's demands for head-on combat.

Later, 4ID arrived and took over from the marines, and hit hard into Balad's Talil Air Base and Tikrit city. The Marines tried to formally turn the area over to MG Ray Odierno's 4ID, with their senior staff meeting with tribal leaders, but Odierno sent only his sergeant major.

Mosul

While there was less Iraqi resistance in the northern city of Mosul, 390km north of Baghdad, with the Iraqi V Corps surrendering without a fight,[55] the Kurdish-Turkish politics were even worse. LTC Robert Waltemeyer, a Special Forces officer in the North, personally pointed a rifle at the lead Kurdish vehicle trying to drive into Mosul, leading to three hours of talk. As a compromise, he sent 30 special operations troops into Mosul to raise an American flag, which was less provocative for the Kurds and Turks.

According to Dr. Sarah D. Shields, associate professor of history at UNC,

Much of the province is included in what the British and U.S. have called the ‘northern no fly zone.’ That region is now the second front....The Turkish government hasn't really given up their claims to the Mosul region, and the Turks are very worried that the Kurds will attain some sort of autonomy in Iraq. Their fear is that that would re-ignite the demands of the Kurds within Turkey for their own autonomy, a situation comparable to the Basques seeking independence from Spain...[US-Kurdish cooperation]... makes the Turks nervous...Kurds promise that they will not tolerate a Turkish invasion. Turks promise they will not tolerate Kurds taking over northern Iraq."[56]

Help came from GEN Jim Jones, NATO Commander, and 26th Marine Expeditionary Unit, which had been afloat in the Mediterranean, commanded by COL A.P. Frick. They landed in Crete, and flew by C-130 and helicopter to Irbil and Bashur. When COL Charlie Cleveland, 10th SFG commander, told Frick his Marines needed to go to Mosul, Frick asked where it was and what he needed to do. When LTC David Hough's first Marine unit reached the Mosul airport, Waltemeyer told the to set up a presence at the airport and in the city.

On the 14th, they were threatened by mobs, and fighters dispersed them with low passes. Additional forces arrived, but Firck, Hough, and Waltemeyer decided that they had to withdraw to the airport the next day. By then, there were 750 Marines at Mosul airport, CENTCOM told them not to land any more.

Osman called Abizaid and said both Kirkuk and Mosul needed more forces. The fastest way to get reinforcements there was by a long airmobile lift by the 2nd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, to Mosul, under COL Jone Mosul. The rest of the 101st, under MG David Petraeus, wa given responsibility for Ninawa Province, including Mosul and Kirkuk. Petraeus, as opposed to Odierno in Tikrit, quickly met with local groups and opened effective dialogue, according to Osman.[57]

Southeast

The Shi'ite southeast was the responsibility of MG Robert Brims and the 1 Armoured Division (UK). MG Albert Whitley, McKiernan's British deputy, had sent humanitarian aid to Umm Qasr on March 28, obtaining some good will. On April 2nd, they took a food warehouse, again to give them humanitarian supplies. [58]

Brims did not want to besiege Basra, which appeared to be under control of militia under "Chemical Ali", Ali Hassan al-Majeed. Brims deliberately left the fedayeen an escape route, to avoid a fight in Basra. 7 Armoured Brigade, under Brigadier Graham Binns, had successfully put a ring around Zubayr, meeting the militia coming out and avoiding a fight in the city. Brims wanted to follow that lesson in Basra.[59]

Moves to accelerate collapse

John Abizaid, deputy CENTCOM commander, called Khalizad in Ankara and asked him to arrange a meeting of exiles in the liberated port of Umm Qasr, and explore if the Iraqi Army might be more willing to surrender to Iraqis. Franks followed up with a call urging the same thing.

Abizaid also called Feith's office, in search of Iraqis to fight with the Americans. William Luti, a senior assistant to Feith, referred Abizaid to COL Ted Seel, who had been a defense attache to Egypt and the CENTCOM liaison to Chalabil. Seel, along with LTG Henry "Pete" Osman, had entered northern Iraq from Turkey, to facilitate U.S. goals there. On the 27th, Abizaid asked if Chalabi could deploy forces in the south as well. Seel asked Chalabi, who was next to him; Seel reduced Chalabi's estimate of 1000 troops in 48 hours to 700. [60]

Frank Miller, the NSC deputy for defense, had never heard of the plan with Chalabi. There had been a plan to train Iraqis in Hungary, pushed by Feith and Wolfowitz but disliked by Franks. It had produced 73 volunteers, being used as interpreters. Miller assumed the CIA was involved, but Tenet told him he knew nothing of the Chalabi plan; there was a separate group with which CIA was involved, the Scorpions.

CIA field personnel told Washington that the Chalabi force contained Iranian mercenaries. Seel vouched for the men, and approximately 570 eventually flew to the south in April. Chalabi insisted on going with them, to which Abizaid objected given that Chalabi was a political operator, not a fighter. Eventually, Chalabi and his men went to Talil. They were unequipped when they arrived; the Air Force had not wanted untrusted armed troops o their aircraft.

McKiernan, who would actually use the fighters, had known nothing of them. They were never used in combat, although Chalabi did deliver a speech at Nasiriyah.

Regime collapse

The Coalition had originally expected a house-by-house fight in Baghdad, and to be attacked with chemical weapons as they came close. Before the invasion, they had expected the greatest resistance to be from the Special Republican Guard, Special Security Organization, and Saddam Fedayeen. It was a surprise when the Fedayeen were among the first defenders, attacking the lines of communications.

Nevertheless, there was a disconnect between on-the-ground reality and the positions taken by Saddam's spokesman.

The main Baghdad operation, leading to regime collapse, was a completely joint effort, using ground, air, and maritime components. It began on April 7. V Corps was responsible for the main ground offensive, prepared by the "five simultaneous attacks" through the Karbala Gap. Its major elements were the heavy 3rd Infantry Division, highly mobile 101st Airborne Division, 3rd Armored Cavalry Regiment and the light 82nd Airborne. The latter two were focused on securing the lines of communication and the flanks. Now in theater, the 4th Infantry Division, which was the most advanced division in the Army, reinforced V Corps. South and EastBaghdad was not the only area of concern; I MEF and the British forces secured the southern oilfields by the 10th and Saddam's home area of Tikrit by the 14th. Northern frontSpecial Operations forces secured the northern oil fields on the 10th. Ramadi surrendered on the 13th. Air operationsThe first Coalition aircraft landed at Baghdad International Airport on April 8. Securing BaghdadOn the 8th, Perkins was in the government center while Mattis and the Marines approached from the east, it was obvious in the world's media that the U.S. was in downtown Baghdad. It was less obvious that Perkins' several thousand soldiers were the only ground force in a city of six million. He was under orders not to cross the Tigris, but was authorized to use artillery and air strikes on targets across that river. The prohibition, however, was to prevent fratricide between Marine and Army ground units. While U.S. forces did not hit other troops, journalists were not as lucky. [61] While U.S. troops had been warned that journalists were in the sl-Rasheed Hotel, neither Blount nor Perkins' brigade had not been told that the Iraqis had moved large numbers of reporters to the Palestine Hotel. Under fire, the brigade mistook reporters' cameras and binoculars for artillery observers, and a tank fired on the hotel, killing two.[62] In a separate incident, al-Jazeera's office was bombed and a journalist killed, which U.S. State Department spokesman Nabil Khoury called "a grave mistake." Al-Jazeera called it deliberate.[61] Major forces began moving into Baghdad on the 9th, establising a much higher level of control. Deputy CENTCOM commander Mike DeLong said three factors made looting much worse than expected:[63]

McKiernan's command post flew into Baghdad International on April 12. He was unsure what help he would receive in reconstruction; there was no provisional Iraqi government and Garner was still in Kuwait. [64] References

|