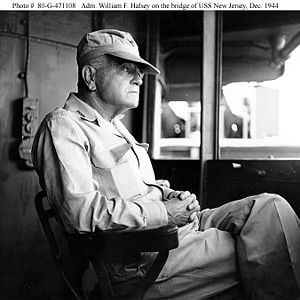

William Halsey

William F. "Bull" Halsey (1882-1959) was a fleet admiral of the U.S. Navy, a colorful and inspirational combat leader in the Second World War. He was also quite controversial in terms of his ability at the level of fleet command, especially at the Battle of Leyte Gulf. One of his most authoritative biographers, E. B. Potter, had begun his work tending to believe that argument, but eventually saw him as

a man not without shortcomings but with qualities of leadership, courage, judgment, good will and compassion that utterly outweigh his faults.[1]

As Halsey points out in his autobiography, "Bull" was the nickname of the press corps, not the Navy. Named for his father, he was first called "Old Bill", then "Bill" in the Navy, and "more recently I suppose it is inevitable for my juniors to think of me, a fleet admiral and five times a grandfather, as "Old Bill" Now that I am sitting down to my autobiography, it is Bill Halsey whom I want to get on paper, not the fake, flamboyant "Bull.""[2] It is a Navy legend, however, that an officer, entering Halsey's darkened command information center during a battle, muttered "is that old goat here?" and received a thunderous response, "Who are you calling old?

Early life and career

Born into a Navy family, he graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1904, specializing in torpedo warfare. "He commanded the First Group of the Atlantic Fleet's Torpedo Flotilla in 1912-13 and several torpedo boats and destroyers during the 'teens and 'twenties. Lieutenant Commander Halsey's First World War service, including command of USS Shaw (Destroyer # 68) in 1918, was sufficiently distinctive to earn a Navy Cross."

In 1922-25, Halsey served as Naval Attache in Berlin, Germany and commanded USS Dale (DD-290) during a European cruise. [3]

Preparing for WWII

Halsey recognized, earlier than other officers, the significance of naval aviation. In 1932, he left destroyer duty, in which he had spent all but one year of his sea duty. He first attended the Naval War College, and then the Army War College, which was then in Washington, DC and focused on the level of national strategy.

Entering aviation

Ernest J. King, then head of the Navy's Bureau of Aeronautics, offered him command of the aircraft carrier USS Saratoga (CV-3) if he would qualify as aircrew by taking the aviation observer course. He did not immediately agree but asked his wife's opinion, and she said she would agree if Admiral William Leahy, then head of personnel for the Navy, agreed. Leahy blessed the idea.

Arriving at the air training center at Pensacola, Floria in July 1934, he changed from the observer to the pilot curriculum. Much older than the usual student pilot, he noted that "my eyes could not pass the tests for a pilot, and how I managed to be classified as one, I honestly don't know yet, and I'm not going to ask." [4]

After his certification of a pilot, he indeed took command of Saratoga, until 1937, when he became commandant at Pensacola. He was selected as a rear admiral in 1937, waiting for an opening fifteen months later.

Force command

In May 1938, he took command of Carrier Division 2 and gained experience in multiple-ship operations. He encouraged discussions of carrier tactics, and appointed a squadron commander, Miles Browning, as his deputy. Thomas Moorer, a future Chief of Naval Operations and Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, said Halsey "had a knack of involving everyone in the discussion." Browning, however, was aloof and condescending. [5] Halsey's loyalty to Browning would be an embarrassment in later years.

In the major fleet problem of early 1939, Halsey's division was under the command of Ernest J. King, then Commander, Aircraft, Battle Fleet, known to be a highly ambitious perfectionist. Halsey was an apt pupil of King, but more than once felt the lash of King's explosive temper. King actually held him in high regard, which was to continue through WWII.

Promotion to Commander of Carriers

Halsey introduced a number of new communications procedures, which became standard, as division commander. On 13 June 1940, he became Commander, Aircraft, Battle Force, with the temporary rank of vice admiral, also commanding Carrier Division 2. In the summer of 1940, he first had the opportunity to work with radar on real warships, and was stunned by its potential.

If had to give credit th the instruments and machines that won us the war in the Pacific, I would rate them in this order: submarines first, radar second, planes third, bulldozers fourth.[6]

On 1 February, Adm. Husband Kimmel replaced Admiral James Robertson as commander of he Pacific Fleet. Kimmel was Halsey's classmate and friend. He was pleased when another old friend, Raymond Spruance, took command of Halsey's cruisers in mid-Sepember. Intelligence showed more and more Japanese preparation, and Halsey attended a November 27 conference on reinforcing Wake Island. His carrier force was ordered to deliver them, and was thus safely out of port when Pearl Harbor was attacked.

Reinforcing Wake

The Wake reinforcement was designated Task Force 2. Once they were clear of the local area, he split off the [[USS Enterprise (CV-6)|USS Enterprise (CV-6), three heavy cruisers and nine destroyers, and designated them Task Force 8. Task Force 2 would feint away from TF 8, which, without the older battleships, was capable of 30 nots.

When TF8 was out of signal range of TF2 and Pearl, he had the Enterprise's captain, George Murray, issue Battle Order No. 1, which included:

- The Enterprise is now operating under war conditions

- At any time, day or night, we must be ready for instant action

- Enemy submarines may be encountered.

He ordered all aircraft armed with live ammunition, and to sink any ship encountered and shoot down any aircraft, having confirmed no Allied shipping was in the area. This was a shock to the task force staff, as only three knew the real mission. His operation officer, William Buracker, confirmed he authorized it, and said "Goddamit, Admiral, you can't start a private war of your own! Who's going to take the responsibility?"

Halsey, who had decided war would ocome in days or hours, and that the delivery of the aircraft was essential, resolved to destroy any Japanese reconnaissance forces before they could report his position. They delivered the planes and turned backto Pearl on December 4, planning to reenter on December 7, but was delayed by the need to fuel destroyers. [7]

Pearl Harbor attacked

Early on the morning of 7 December, the task force sent 18 of it aircraft ahead to land at the Ford Island naval air station at Pearl Harbor. When the first report of an air raid on Pearl Harbor was received, Halsey realized that the base had not been notified about his incoming aircraft, and assumed that U.S. antiaircraft gunners were shooting at them. As he rushed to inform Ford Island, the first alerts began to arrive, specifically identifying Japanese aircraft at 0823. Kimmel, at 0923, broadcast that a state of war existed with Japan, and, at 0921, ordered TF3, a heavy cruiser and destroyers, and TF 12, the USS Lexington and screen to join Halsey. All ships at Pearl that were still operational were ordered to sortie as TF 2 and join Halsey, giving him operational control of every ship at sea. Potter quoted a comment from Halsey, years afterward, "I have the consolation of knowing that, on the opening day of the war, I did everything in my power to find a fight." Potter's opinion was that even after reflection, "it did not occur to him that it might have been a mistake to expose America's slender carrier forces to ruinous odds."[8]

Five of the eighteen Enterprise aircraft indeed were shot down by U.S. gunners. At 1330, the Department of the Navy broadcast the declaration of war. Enerprise and her destroyers sent out patrols into the night, but found nothing. Halsey himself was not unhappy he did not meet the Japanese force, because he had only cruisers to oppose battleships. Air strikes, especially when the Lexington joined him, was a possibility, but he had limited reconnaissance resources and could not find the force. By evening of the 8th, he returned to Pearl.

On seeing the wreckage, he muttered a phrase that would resonate through the fleet: "Before we're through with them, the Japanese language will be spoken only in hell!" [9]

Senior command

His senior command experience was at three levels:

- Pearl Harbor to 28 May 1942: task force command; then on the sick list

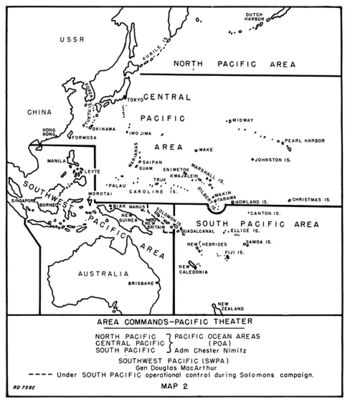

- 18 October 1942 to 15 June 1944: commander of the South Pacific Area

- 16 June to end of war: Third Fleet command

Task Force

South Pacific Area

After being medically approved to return to duty, he was named to command a carrier task force in the South Pacific Area. Since the ships were still being readied, he began a familiarization trip to the area on 15 October 1942, arriving at the Noumea area headquarters on the 18th. After Pacific commander Chester W. Nimitz concluded that VADM Robert Ghormley had become dispirited and exhausted. As Halsey's aircraft came to a stop at Noumea, Ghormley's flag lieutenant met him before he could board the flagship, giving him a sealed envelope containing a message from Nimitz:

YOU WILL TAKE COMMAND OF THE SOUTH PACIFIC AREA AND SOUTH PACIFIC FORCES IMMEDIATELYHalsey was "apprehensive" because he "knew nothing about campaigning with the Army, much less with Australian, New Zealand, and Free French forces. Second, although I knew little about the military situation in the South pacific, I knew enough to know it was desperate...lastly, I was regretful because Bob Ghormley, whom I was relieving, had been a friend of mine for forty years."[10]

Carl Solberg, an intelligence officer on Halsey's staff, wrote that Halsey was kept ashore at Noumea, after his early task force leadership, to provide motivation for demoralized U.S. forces in the South Pacific. Once they began to operate independently, the new system of fleet command was instituted.[11]

Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal, where a long battle was still active, was the most critical spot in his Area. While he had planned to visit it on the inspection trip, Nimitz had cancelled that stop, presumably to speed his relief of Ghormley. He was faced with an immediate decision: should there be another air base to supplement Guadalcanal's Henderson Field, which the Japanese were able to neutralize temporarily? The closest existing field was at Espiritu Santu, 600 miles away. Ghormley had planned to build an airport 200 miles closer, on Ndeni in the Santa Cruz Islands.

Archer Vandegrift, the Marine commander on Guadalcanal, said he could not spare anyone to build the Ndeni field. Halsey concluded that he could not decide the airfield issue without firsthand knowledge of Guadalcanal, so he asked Vandegrift to come to Noumea. The meeting, on 23 October, included Commandant of the Marine Corps Thomas Holcomb, Major Genera Millard Harmon, U.S. Army commander for the area; Major General Alexander Patch, commanding Army forces in New Caledonia; and "Kelly" Turner, Commander, Amphibious Force, South Pacific.

The next day, without Nimitz's permission, he cancelled the Ndeni operation and sent its resources to Vandegrift. Another issue had been that Turner, in charge of the ships supporting Vandegrift ashore, was interfering with Marine decisions. Halsey concurred with Holcomb that the commander of a landing force should be co-equal with the amphibious commander, which became the standard for future operations.[12]

Fleet command

In the Pacific War, the United States obtained much better usage of its warships than did the Japanese, as most of the combat vessels stayed at sea, with extensive logistical support. For the same set of ships, however, there were two command staffs. One set would conduct an operation from the flagship, while the other would stay on shore to plan the next operation.

When the operating warships were under Halsey, they were designated United States Third Fleet. United States Fifth Fleet was their designation when commanded by Vice Admiral Raymond Spruance. Reflecting the alternation of the top command between Halsey (Third Fleet) and Spruance (Fifth Fleet), there were two major type-specific task forces that kept the same ships but changed numbers, not necessarily acting as an active command level in a particular engagement.

- TF 38/TF 58: Fast Carriers Pacific Fleet, under VADM Marc Mitscher and, later, John McCain Sr.

- TF 34/TF 54: Battleships Pacific Fleet, under VADM Willis Lee

The carriers, battleships, and lighter ships primarily were distributed into four task groups

| ID & CO | Fleet carrier | Light carrier | Battleship | Heavy cruiser | Light cruiser | Destroyer |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TG 38.1

VADM John McCain Sr. |

2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 15 |

| TG 38.2

RADM Gerald Bogan |

3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 17 |

| TG 38.3

RADM Frederick Sherman |

2 | 2 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 14 |

| TG 38.4

RADM Ralph Davison |

2 | 2 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 11 |

Fleet Admiral and later life

Halsey was the last Navy officer promoted to the special rank of Fleet Admiral. Four such promotions were authorized for the Navy, although William Leahy was arguably a White House rather than Navy officer.

Halsey's peer, Raymond Spruance, as or more highly respected in the Navy than Halsey, was blocked for the promotion by Congressional politics.

References

- ↑ E. B. Potter (1985), Bull Halsey, U.S. Naval Institute, ISBN 0870211463, p. xiii

- ↑ William F. Halsey and J. Bryan III (1947), Admiral Halsey's Story, McGraw-Hill, p. 1

- ↑ Fleet Admiral William F. Halsey, Jr., USN, (1882-1959), Navy Heritage and Historical Command (formerly Naval Historical Center)

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 56

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 139-140

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, p. 69

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 75-76

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, p. 12

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 79-81

- ↑ Admiral Halsey's Story, pp. 109-111

- ↑ Carl Solberg (1995), Decision and dissent: with Halsey at Leyte Gulf, U.S. Naval Institute, ISBN 1557509710, pp. 14-15

- ↑ Potter, Bull Halsey, pp. 161-162