Semantic primes

Introduction

- See also Linguistic universals

The term 'semantic primes' refers to a relatively small set of words (<100 words) that specify concepts whose meanings cannot be described in terms of other, simpler, non-semantic-prime words. The description of the meanings of non-semantic-prime words ultimately require use of words from a set—the semantic primes. Children learn the implicit meanings of the words in this set from the ways they are used by other speakers in every day conversation. Consider, for example the semantic prime, HEAR. As a child's elders use the word HEAR repeated in a large variety of ordinary conversational situations, the child comes to associate the word with what it means in the context of the situation. The word/concept HEAR can subsequently be used in the description of many other words (e.g., audible, whisper, oration), but no words simpler or more basic than HEAR can be used to describe the meaning of HEAR. The dictionary's definition of HEAR uses words whose meanings ultimately depend on knowing the meaning of HEAR.

| In natural semantic metalanguage (NSM) [see text], all humans have a set of semantic primes; in other words, a set of innate concepts which are then encoded into language. |

| The words resulting from the encoding are called “semantic primes”, or “semantic primitives”, because they are necessary in order to explain other words. |

| They do not have their own definition; in fact, no definition is really possible since their meaning is acquired and inferred from one’s innate concepts and environment. |

| More specifically, humans inherit semantic primes as part of their genetic material which, in turn, comes from a shared ancestry. |

| As a result, although languages evolved differently and the sounds by which primes are expressed differ from one language to the next, the list of primes is essentially universal. |

| Basic language structure, or syntax, is produced from combining primes. |

Linguist Anna Wierzbicka, in her book, Semantics: Primes and Universals (Wierzbicka, 1996), presents an argument, grounded in biologically plausible hypotheses and experimental observations, that all humans possess as part of their inherited human faculties the same basic relatively small set of innate 'concepts', or perhaps more precisely, a non-conscious propensity and eagerness to acquire those concepts and encode them in sound-forms (words). The words those concepts encode Wierzbicka calls semantic primes, or alternatively, semantic primitives — 'semantic' because linguists have assigned 'semantic' in reference to the meaning of words (=linguistic symbols). Words that qualify as semantic primes, words such as ME, YOU, THING, UP, DOWN, BEFORE, AFTER, EXIST, HEAR, WANT, need no definition in terms of other words, and in fact one cannot define them in simpler words, without creating a closed set of words with a circularity of definitions that ultimately precludes providing meaning for any word. Semantic primes solve the circularity problem by providing a basic set of words whose meanings we know and use meaningfully without having to define them. They allow us to construct other words defined by them. Semantic primes 'prime' language semantics.

Moreover, according to Wierzbicka and colleagues, as modern human beings who share the same set of types of inherited determinants that make us human (i.e., the human genome), all our different natural languages, despite the diversity of language families, share the same basic set of innate concepts, or share the same propensity and eagerness to encode the same set of concepts in words. Our common grandmother and grandfather many generations removed may have encoded those concepts in a specific vocabulary, and therefore had the original set of semantic primes. The dispersal of their descendants from their African homeland throughout the world enabled the evolution of many different languages, each with a unique set of sound-forms for their words. Nevertheless the same set of semantic primes remained within each language, though expressed in differing sound-forms. Thus, as Wierzbicka argues, all modern humans have the same set of semantic primes, though not the same set of sound-forms expressing them, rendering semantic primes cross-culturally universal.

The definitional circularity problem

Definitions, too, are closed groups of terms.

|

Suppose you, as a bright child, have an excellent dictionary of the English language — The New Oxford American Dictionary or The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, say — and you try to use it to learn the 'meaning'[3] of all the words therein, because you lack confidence that you use in a meaningful way all the words you ordinarily use, and because you want to learn the meanings of all the other words your elders speak. In your dictionary you will find every entry-word defined in terms of other words, of course. In your determination to learn the meaning (or meanings) of every word in the dictionary, you find you need look up definitions of the words employed in the definitions of every word. But sooner or later you will find that you cannot complete your task — learning the meaning of every word in the dictionary — because every word’s description of meaning employs other entry-words whose meaning you also wish to firmly establish in your mind. You find you have embarked on a circular task, not surprisingly, because the dictionary comprises only a closed set of words, finite in number, that enable descriptions of the meanings of each other.[4]

If you do not already have in your mind a set of basic words whose meanings you somehow happen to have come to know independently, without the need of words to define them — even though you came to associate that set of basic words with their meanings by listening to your elders speaking them — you will remain forever in a continuous circular loop in your dictionary, and fail to achieve your goal.

We can now state the fundamental requirement for a word to have 'meaning', according to Wierzbicka and colleagues: one must already have in one's mind a set of basic words (semantic primes) whose meanings (concepts) one somehow happens to come to know, or develop, independently, without the need of words to define them. Would seem of little difficulty for a child just learning to speak to come to know the meaning of the semantic prime, MORE, when the child repeatedly hears the sound of MORE associated with the sounder receiving what we call 'more'.

In this article we will elaborate on Wierzbicka’s theory (Wierzbicka, 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka (eds.), 1994); exemplify the list of semantic primes; show how they underlie the meaning of the non-primes in our language; give some of the experimental observations that support the claim of semantic primes as universal among human languages; discuss the contributions and comments of other linguists and scholars from other disciplines; and indicate how far back we can trace the history the idea of semantic primes by any other name.

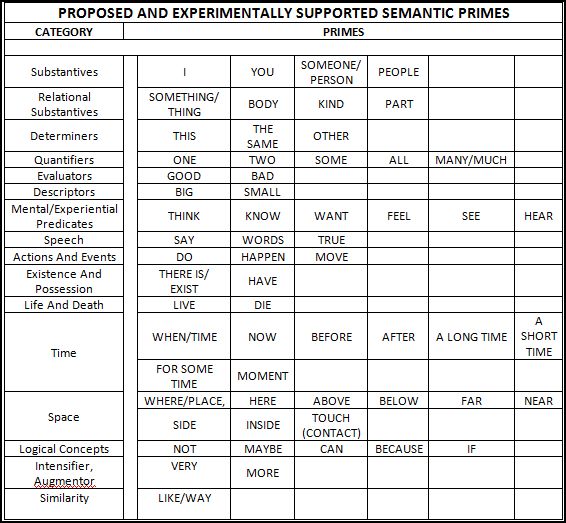

List of semantic primes

Consider Wierzbicka’s colleague, Cliff Goddard's words:

When Wierzbicka and colleagues claim that DO, BECAUSE, and GOOD, for example, are semantic primes, the claim is that the meanings of these words are essential for explicating the meanings of numerous other words and grammatical constructions, and that they cannot themselves be explicated in a non-circular fashion. The same applies to other examples of semantic primes such as: I, YOU, SOMEONE, SOMETHING, THIS, HAPPEN, MOVE, KNOW, THINK, WANT, SAY, WHERE, WHEN, NOT, MAYBE, LIKE, KIND OF, PART OF. Notice that all these terms identify simple and intuitively intelligible meanings which are grounded in ordinary linguistic experience (Goddard, 2002).

ALL PEOPLE KNOW ALL WORDS BELOW BECAUSE WHEN SMALL BODY THEY HEARD THE WORDS SPOKEN A LONG TIME:[5]

A universal syntax of meaning

Semantic primes represent universally meaningful concepts, but to have meaningful messages, or statements, such concepts must combine in a way that they themselves convey meaning. Such meaningful combinations, in their simplest form as sentences, constitute the syntax of the language. Wierzbicka provides evidence that just as all languages use the same set of semantic primes, they also use the same, or very similar syntax. She states: "I am also positing certain innate and universal rules of syntax-not in the sense of some intuitively unverifiable formal syntax a la Chomsky, but in the sense of intuitively verifiable patterns determining possible combinations of primitive concepts" (Wierzbicka, 1996). She gives one example comparing the English sentence, "I want to do this", with its equivalent in Russian. Although she notes certain formal differences between the two sentence structures, their semantic equivalence emerges from the "....equivalence of the primitives themselves and of the rules for their combination."

This work [of Wierzbicka and colleagues] has led to a set of a highly concrete proposals about a hypothesised irreducible core of all human languages. This universal core is believed to have a fully ‘language-like’ character in the sense that it consists of a lexicon of semantic primitives together with a syntax governing how the primitives can be combined (Goddard, 1998).

It might strike many as not particularly surprising that all humans today possess a common language core of semantic primes and a more or less universal syntax, inasmuch as modern science teaches that all humans today descended from a common speech-enabled male and female Homo sapiens ancestor living in Africa before the exodus of a founder group that left Africa and dispersed throughout the world into at first many geographically separate groups developing into different so-call races. Linguist Johanna Nichols traces Homo sapiens language origin as far back as 130,000 years ago, perhaps only 65,000 years after the earliest Homo sapiens fossil finds (Adler, 2000). Philosopher G. J. Whitrow expresses it:

....despite the great diversity of existing languages and dialect, the capacity for language appears to be identical in all races. Consequently, we can conclude that man's linguistic ability existed before racial diversification occurred (Whitrow, 1988).

Natural Semantic Metalanguage (NSM): meaning and grammar

In effect, the combination of a set of semantic primes each representing a different basic concept, residing in minds with a propensity to acquire certain basic concepts, and a common set of rules for combining those concepts into meaningful messages, constitutes a natural semantic prime language, or natural semantic metalanguage (NSM).[6] In English, the natural semantic metalanguage reduces language to a core that enables full development of the English language. A new word can be added as a shorthand substitute for a 'text' in the natural semantic metalanguage, a 'text' that can convey what English speakers mean by happy, by what a person does when he says something not true because he wants someone to think it true, and by what has happened if something made in one part has had something happen to it making it now two parts, or many parts. Any English word can be described (defined) with a text using a primitive lexicon of about 60 words (concepts) in the English natural semantic metalanguage. Likewise can any complex semantic sentence in English be paraphrased reductively to the core words and syntax of the natural semantic metalanguage.

The texts in NSM can make subtle distinctions English-speakers make between happy, glad, joyful, ecstatic, etc., and can supply those distinctions to those who want to know them.

Given the universal nature of the list of semantic primes among languages, and of the grammar, every language has essentially the same natural semantic metalanguage, though each semantic prime sounds different among languages and the appearance of the syntax may differ. Wierzbicka and colleagues refer to all the natural semantic metalanguages as 'isomorphic' with each other.

Conceivably, if the dictionary of meaning descriptions of each language was reductively paraphrased in the text of its natural semantic metalanguage, and that natural semantic metalangugage was translated to a common natural semantic metalanguage for all natural languages, it would greatly reduce language barriers.

The Natural Semantic Metalanguage does not strictly separate grammar (syntax) and meaning:

In the NSM framework, meaning and grammar are seen as inseparable. For the sake of brevity and convenience, the sixty-odd semantic primes can be described as lexical, but in fact their true nature is lexico-grammatical. In every language, each element has its own lexical (phonological) embodiment (and, in many cases, several such embodiments, i.e. lexical variants or "allolexes"); and at the same time, each element has its own set of grammatical (combinatorial) properties. The actual configurations lexically, phraseologically or grammatically encoded in different languages are language-specific, but the rules of combination are the same in all languages, and it is possible to enumerate, for each prime, all its combinatorial possibilities. Thus, each conceptual prime has its own conceptual grammar, and this grammar is as universal as the prime itself. For instance, in all languages the prime I can be combined with the prime can, the prime can with the prime not, and the prime move with the prime can and with the prime something, to form scntenccs such as ll can't move' and 'this thing is moving'. The combined grammatical properties of all the primes constitute a genuine universal grammar: the primes themselves, together with their combinatorial properties, form a system in which...everything hangs together. This system constitutes the indivisible conceptual core of all human languages. The proposed model of universal grammar, i.e. the inherent syntactic properties of all universal semantic primes, is described in detail in Goddard & Wierzbicka (2002) (Peeters 2006).

Semantic molecules

One might conceive of semantic primes as the 'atoms' of language. In chemistry, atoms of differnt types, or species, i.e., atoms of different chemical elements, can combine to form molecules, such as amino acids, in a variety of types depending on the particular combination of element atoms. Such chemical molecules in turn can combine to form more complex molecules, such as proteins. A somewhat analagous dynamic occurs with the atoms of language, viz., semantic primes, when they combine to form 'semantic molecules'.

NSM researchers recognise that some explications necessarily incorporate certain complex semantic units, termed "semantic molecules". These are non-primitive meanings (hence, ultimately decomposable into semantic primes) that function as units in the semantic structure of other, yet more complex words. The notion is similar to that of “intermediate-level concepts” in the Moscow School of Semantics, but with the additional constraint that semantic molecules must be meanings of lexical units in the language concerned...From a conceptual point of view, the NSM claim is that some complex concepts are semantically dependent on other less complex, but still non-primitive, concepts.[6]

Semantic molecules possess a higher level of complexity of conceptualization than do the semantic atoms comprising them, and although they are not conceptual primitives, we can readily decompose them into their constituent conceptual primitive parts. The concept, 'visible', for example, decomposes to the conceptual primitives, 'I', 'can', 'see', 'this' — or some similar combination. In turn, 'visible' can combine with semantic primes and/or other semantic molecules to yield other non-primitive concepts, such as 'invisible', or 'moon'.

Many semantic molecules are language-specific, but it appears that a limited number, perhaps 20 or so, may be universal or near-universal. These include some body-part words, such as 'hands', some environmental terms, such as 'sky' and 'ground', and some basic social categories, such as 'children', 'women', and 'men'. Semantic molecules be "nested", enabling a great compression of semantic complexity.[6]

Notes

- ↑ Axiological Cognition and its Applications in Complex Psychological Assessment

- ↑ Aristotle, 350 BCE. De Anima Internet Classic Archive, On the Soul, translated by J.A. Smith.

- ↑ We leave the definition of the 'meaning' of a word for the time being, assuming the reader has an intuitive understanding of a word's 'meaning'. Shortly we will see the fundamental requirement for a word to have 'meaning', as argued by Wierzbicka and colleagues.

- ↑ To further exemplify the circularity issue, consider that with a child on the brink of speech, you could not teach her how to recognize and pronounce every word in the dictionary and then expect her to go from there to learn every word's definition just by using the dictionary.

- ↑ A sentence using only semantic primes.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 NSM Semantics in brief. University of New England. School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences. Linguistics.

References cited

- Adler R. (2000) “Voices from the past” New Scientist, 26 February.

- Goddard C. (1998) Bad arguments against semantic primitives. Theoretical Linguistics 24:129-156. View/Download PDF of article [Goddard: "....this paper is heterogenous in nature and polemical in purpose...."]

- Goddard C. (2002) The search for the shared semantic core of all languages. In Cliff Goddard and Anna Wierzbicka (eds). Meaning and Universal Grammar - Theory and Empirical Findings. Volume I. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 5-40. View/Download PDF of the book chapter

- Goddard C., Wierzbicka A. (eds.) (1994) Semantic and Lexical Universals: Theory and Empirical Findings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Publisher’s website’s description of book, with Table of Contents

- Peeters B. (2006) Semantic primes and universal grammar: empirical evidence from the Romance languages. John Benjamin Publishing Company. ISBN 9789027230911.

- Whitrow GJ. (1988) Time in History: The evolution of our general awareness of time and temporal perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-215361-7. p. 11.

- Wierzbicka A. (1996) Semantics: Primes and Universals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198700024. Publisher’s website’s description of book Professor Wierzbicka’s faculty webpage Excepts from Chapters 1 and 2