Talk:Microorganism

The gap from Leeuwenhoek to Pasteur is a very long one. When L is mentioned, Would it be better to talk about why L. did do than what he did not.?DavidGoodman 21:02, 24 November 2006 (CST)

- The statments that visible /invisible have exceptions occurs at least 5 times, 1 in each section.

- The section on eukaryotic microorganisms neeeds to specifiy just what is included--a good trick--(my first research exerience was in protozoology, as it was then called). As you undoubtedly intend to include fungi, you'll have to explain that they are not plants. We should probably do a fngii article fairly early on. I'll start one from WP.DavidGoodman 20:51, 25 November 2006 (CST)

Complete rewrite

I think this article starts badly and is boring bland. I propose to start from scratch and De WP edia it. This will take time. I will do it so that access to the current one is preserved. An I am giving fair notice, in case there is disagreement. Im the only one to edit it here anyway. David Tribe 07:29, 17 March 2007 (CDT)

NEW DRAFT OF ARTICLE

Some unicellular protists and unusually large bacteria (Epulopiscium fishelsoni and Thiomargarita namibiensis) are visible to the naked eye [1]

The study of micro-organisms is called microbiology.

Importance

Habitats and ecology

Extremophiles

Use in food

Use in science

Microorganisms and human health

Infectious disease

Hygiene

History

Evolution

Discovery

Before Anton van Leeuwenhoek's invention of the microscope and discovery of microorganisms with it in 1676, it had been a mystery as to why grapes could be turned into wine, milk into cheese, or why food would spoil. Leeuwenhoek did not make the connection between these processes and microorganisms, but he did establish that there were forms of life that were not visible to the naked eye. Leeuwenhoek's discovery, along with subsequent observations by Lazzaro Spallanzani and Louis Pasteur, ended the long-held belief that life could spontaneously appear from non-living substances.

Spallanzani found that microorganisms could only settle in a broth if the broth was exposed to the air; he also found that boiling the broth would sterilise it, killing the microorganisms. Pasteur expanded upon these findings by exposing boiled broths to the air in vessels that contained a filter to prevent all particles from entering, or in vessels with no filter but with air being admitted via a curved tube that would not allow dust particles to come into contact with the broth. By first boiling the broth, Pasteur ensured that there were no microorganisms alive in the broths at the start of his experiment. Nothing grew in the broths during his experiments, showing that the living organisms that grew in such broths came from outside, as spores on dust, rather than spontaneously generated within the broth. Thus, Pasteur decisively refuted the theory of spontaneous generation and supported germ theory.

In 1876, Robert Koch showed that microbes can cause disease, by showing that the blood of cattle that were infected with anthrax always contained large numbers of Bacillus anthracis. Koch also found that he could transmit anthrax from one animal to another by taking a small sample of blood from the infected animal and injecting it into a healthy one, causing the healthy animal to become sick. He also found that he could grow the bacteria in a nutrient broth, inject it into a healthy animal, and cause illness. Based upon these experiments, he devised criteria for establishing a causal link between a microbe and a disease in what are now known as Koch's postulates. Though these postulates are no longer strictly accurate, they remain historically important in the development of scientific thought.

Classification

Microorganisms can be found in almost all branches of the taxonomic organization of life on the planet. Bacteria and archaea are almost always microscopic, whilst a number of eukaryotes are also microscopic, including most protists and a number of fungi. Increasingly, the practical identification and classification of micro-organisms is being based on the genetic code, that is, the nucleotide sequence of the RNA in the small ribosome subunit [3] . Viruses are generally regarded as not living in the same sense as other organisms and are, strictly speaking, not microbes, although the field of microbiology also encompasses the study of viruses.

Bacteria

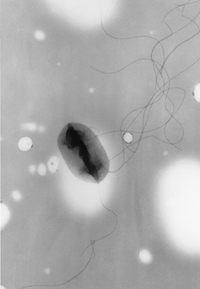

Bacteria, sometimes called eubacteria (true bacteria) to distinguish them from Archaea (formerly called archeobacteria) are structurally the simplest and biochemically the most diverse and widespread organisms on Earth. Generally they consist of simple rod-like or spherical (coccus, pl. cocci) cells about 1 micron in size without a defined nucleus (and are thus classified as prokaryotes but also classified as Monera in the alternative five-kingdom taxonomy) (see Bacterial cell structure}.

Bacteria are practically all invisible to the naked eye, with few extremely rare exceptions, such as Thiomargarita namibiensis. They are unicellular organisms and lack organelles. Their genome is a single string of DNA, although they can also harbour small pieces of DNA called plasmids. Bacteria are surrounded by a cell wall. They reproduce by binary fission. Some species form spores, but for bacteria this is a mechanism for survival, not reproduction. Their generation time can be as short as 15 minutes.

Bacteria inhabit practically all environments where some liquid water is available and the temperature is below +140 °C. They are found in sea water, soil, human gut, hot springs and in food. Practically all surfaces which have not been specially sterilised are covered in bacteria. The number of bacteria in the world is estimated to be around five million trillion trillion, or 5 × 1030.[4]

Archaea

Archaea are single-celled organisms lacking defined nuclei and are therefore prokaryotes. They were originally identified in extreme environments, but have since been found in diverse types of habitats. A single organism from this domain has been called an 'archaean'. Although archaea are superficially similar to bacteria when viewed through the light microscope, consisting of rods or cocci a micron or two in size, the details of their chemistry and molecular structure show they have distinct differences from bacteria, for instance in their membrane fats which employ a different stereo isomer of glycerol phosphate in the membrane fat, are ether rather than ester derivatives of glycerol (glycerol di-ethers and tetra-ethers), and based on the isoprenes to form the hydrophobic chain of the fats. These fundamental differences in biochemistry fit with the concept that Archaea and Bacteria diverged in evolution very early in the history of life [5].

Eukaryotes

All living things, including humans, which are individually visible to the naked eye are eukaryotes, with some exceptions, such as Thiomargarita namibiensis. However, many eukaryotes are also microorganisms. Eukaryotes are characterised by the presence of organelles in the cells; these structures are absent in bacteria and archaea. The nucleus is an organelle which houses the DNA.[6] A mitochondrion is vital in production and conversion of energy inside a cell. The mitochondr]] have evolved from symbiotic bacteria. Plant cells also have cell walls and chloroplasts in addition to other organelles. Chloroplasts produce energy from light by photosynthesis. They were also originally symbiotic bacteria.

Unicellular eukaryotes consist of a single cell throughout their life cycle (note that most multicellular eukaryotes consist of a single cell at the beginning of their life cycles). Unicellular organisms usually contain only a single copy of their genome when not undergoing cell division, although some organisms have multiple cell nuclei (see coenocyte). However, not all microorganisms are unicellular. Microbial eukaryotes can have multiple cells.

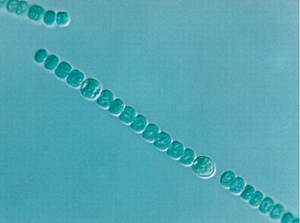

Of the eukaryotic groups, the protists are always unicellular, and thus microorganisms. This is a diverse group of organisms which do not fit into other groups of eukaryotes. Several algae species are unicellular plants. The fungi also have several unicellular species, such as baker's yeast (Saccharomyces cerevisiae). Animals are always multicellular, although they may not be visible to the naked eye.

Microorganisms in fiction

Microorganisms have frequently played an important part in science fiction, both as agents of disease, and as entities in their own right. Some notable uses of microorganisms in fiction include:

- The War of the Worlds, where microorganisms play important thematic and plot-related roles.

- Fantastic Voyage, in which some scientists are miniaturised to microscopic size and observe microorganisms from a new perspective

- Blood Music, in which a colony of microorganisms is given intelligence

- The Andromeda Strain, in which extraterrestrial microorganisms kill several people

References

Citations

- ↑ Annu Rev Microbiol. 2001;55:105-37. Big bacteria. Schulz HN, Jorgensen BB.

- ↑ Dairy Microbiology. University of Guelph. Retrieved on 2006-10-09.

- ↑ Ribosomal Database Project II

- ↑ University of Georgia Campus News

- ↑ Pace Norman R. (2001) The universal nature of biochemistry PNAS vol. 98 no. 3 p 805-808

- ↑ "Eukaryota: More on Morphology." [1] (Accessed 10 October 2006)

Further reading

- Dixon, Bernard (1994). Power Unseen: How Microbes Rule the World, 1st ed.. W. H. Freeman, Oxford and New York. ISBN 0-7167-4504-6.

- Krasner, Robert I. (2002). The Microbial Challenge: Human-Microbe Interactions, 1st.. ASM Press, Washington, DC. ISBN 0-13-144329-4.

- Knoll, Andrew H. (2003). Life on a Young Planet: the First Three Billion Years of Evolution on Earth, 1st ed.. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-00978-3.

- Postgate, John (1992). Microbes and Man, 3rd ed.. Cambridge University Press, UK. ISBN 0-521-42355-4.

External links

- The largest bacteria

- Tree of Life

- Videos of bacteria swimming and tumbling, use of optical tweezers and other fine videos.

- More movies of growing bacteria

- Planet of the Bacteria by Stephen Jay Gould

- Major Groups of Prokaryotes

- Microbe News from Genome News Network

- BBC News, 28 September, 2001: The microbes that 'rule the world' Citat: "... The Earth's climate may be dependent upon microbes that eat rock beneath the sea floor, according to new research....The number of the worm-like tracks in the rocks diminishes with depth; at 300 metres (985 feet) below the sea floor, they become much rarer..."

- BBCNews: 16 January, 2002, Tough bugs point to life on Mars Citat: "...This research demonstrates that certain microbes can thrive in the absence of sunlight by using hydrogen gas..."

- BBCNews: 17 January, 2002, Alien life could be like Antarctic bugs

- Microbiology