Clausius-Clapeyron relation: Difference between revisions

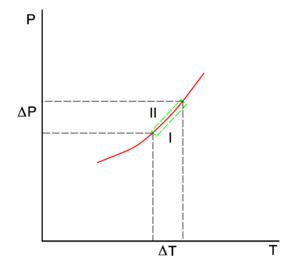

imported>Paul Wormer (New page: {{subpages}} {{Image|Clapeyron.png|right|300px|The red line in the P-T diagram is the coexistence curve of two phases: I and II. For instance, ''II'' is the vapor and ''I'' the liquid ph...) |

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

||

| Line 8: | Line 8: | ||

\frac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}T} = \frac{Q}{T\,(V^{II} - V^{I})} , | \frac{\mathrm{d}P}{\mathrm{d}T} = \frac{Q}{T\,(V^{II} - V^{I})} , | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

where ''Q'' is the molar heat of transition (heat necessary to bring one mole of the compound from phase ''I'' into phase ''II''), ''T'' is the absolute temperature (the abscissa of the point where the slope is computed), ''V''<sup>''I''</sup> is the molar volume of phase ''I'' at the pressure and temperature of the point where the slope is considered and ''V''<sup>''II''</sup> is the same for phase ''II''. The quantity ''P'' is the absolute pressure. | where ''Q'' is the molar heat of transition (heat necessary to bring one mole of the compound from phase ''I'' into phase ''II''). For instance, when phase ''I'' is a liquid and phase | ||

''II'' is a vapor then ''Q'' ≡ ''H''<sub>v</sub> is the molar [[heat of vaporization]]. Further ''T'' is the absolute temperature (the abscissa of the point where the slope is computed), ''V''<sup>''I''</sup> is the molar volume of phase ''I'' at the pressure and temperature of the point where the slope is considered and ''V''<sup>''II''</sup> is the same for phase ''II''. The quantity ''P'' is the absolute pressure. | |||

The equation is named after [[Émile Clapeyron]], who derived it around 1834, and [[Rudolf Clausius]]. | The equation is named after [[Émile Clapeyron]], who derived it around 1834, and [[Rudolf Clausius]]. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 18: | ||

G^{I}(P,T) = G^{II}(P,T). \, | G^{I}(P,T) = G^{II}(P,T). \, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

The molar Gibbs free energy of phase α (''I'' | The molar Gibbs free energy of phase α (α = ''I'', ''II'') is equal to the [[chemical potential]] | ||

μ<sup>α</sup> of this phase. Hence the equilibrium condition can be | μ<sup>α</sup> of this phase. Hence the equilibrium condition can be | ||

written as, | written as, | ||

| Line 27: | Line 28: | ||

phase ''I'' and ''II'', respectively, while the system stays in equilibrium, | phase ''I'' and ''II'', respectively, while the system stays in equilibrium, | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\mu^{I} | \mu^{I}+\Delta \mu^{I} = \mu^{II}+\Delta \mu^{II} | ||

\;\Longrightarrow\; | \;\Longrightarrow\; | ||

\Delta \mu^{I} | \Delta \mu^{I} = \Delta \mu^{II} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

From classical thermodynamics it is known that | From classical thermodynamics it is known that | ||

| Line 49: | Line 50: | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

where ''Q'' is the amount of heat necessary to convert one mole of | where ''Q'' is the amount of heat necessary to convert one mole of | ||

compound from phase ''I'' into phase ''II'' | compound from phase ''I'' into phase ''II''. Elimination of the entropy and taking the limit of infinitesimally small changes in ''T'' and ''P'' gives the ''Clausius-Clapeyron | ||

equation'', | equation'', | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

| Line 59: | Line 59: | ||

The Clausius-Clapeyron equation is exact. When we make the following assumptions we may perform the integration: | The Clausius-Clapeyron equation is exact. When we make the following assumptions we may perform the integration: | ||

* The [[molar volume]] of phase ''I'' is negligible compared to the molar volume of phase ''II'' | * The [[molar volume]] of phase ''I'' is negligible compared to the molar volume of phase ''II'': ''V''<sup>''II''</sup> >> ''V''<sup>''I''</sup>. In general, far from the [[critical point]], this inequality holds well for liquid-gas transitions. | ||

* Phase ''II'' satisfies the [[ideal gas law]] | * Phase ''II'' satisfies the [[ideal gas law]] | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

PV^{II} = R T \, | PV^{II} = R T \, | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

* The transition heat ''Q'' is constant over the temperature integration interval. The | :If phase ''II'' is a gas and the pressure is fairly low this assumption is reasonable. | ||

* The transition heat ''Q'' is constant over the temperature integration interval. The integrations run from the lower temperature ''T''<sub>1</sub> to the upper temperature ''T''<sub>2</sub> and from ''P''<sub>1</sub> to ''P''<sub>2</sub>. | |||

Under these condition the Clausius-Clapeyron equation becomes | Under these condition the Clausius-Clapeyron equation becomes | ||

| Line 80: | Line 81: | ||

\ln\frac{P_2}{P_1} = -\frac{Q}{R}\;\left( \frac{1}{T_2} - \frac{1}{T_1} \right) | \ln\frac{P_2}{P_1} = -\frac{Q}{R}\;\left( \frac{1}{T_2} - \frac{1}{T_1} \right) | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

where ln is the natural (base ''e'') [[logarithm]]. | where ln is the natural (base ''e'') [[logarithm]]. We reiterate that for gas-liquid transitions ''Q'' is the [[heat of vaporization]]. | ||

Revision as of 08:55, 11 September 2009

The Clausius–Clapeyron relation, is an equation for a phase transition between two phases of a single compound. In a pressure–temperature (P–T) diagram, the line separating the two phases is known as the coexistence curve. The Clausius–Clapeyron relation gives the slope of this curve:

where Q is the molar heat of transition (heat necessary to bring one mole of the compound from phase I into phase II). For instance, when phase I is a liquid and phase II is a vapor then Q ≡ Hv is the molar heat of vaporization. Further T is the absolute temperature (the abscissa of the point where the slope is computed), VI is the molar volume of phase I at the pressure and temperature of the point where the slope is considered and VII is the same for phase II. The quantity P is the absolute pressure.

The equation is named after Émile Clapeyron, who derived it around 1834, and Rudolf Clausius.

Derivation

The condition of thermodynamical equilibrium at constant pressure P and constant temperature T between two phases I and II is the equality of the molar Gibbs free energies G,

The molar Gibbs free energy of phase α (α = I, II) is equal to the chemical potential μα of this phase. Hence the equilibrium condition can be written as,

which holds along the red (coexistence) line in the figure.

If we go reversibly along the lower and upper green line in the figure, the chemical potentials of the phases change by ΔμI and ΔμII, for phase I and II, respectively, while the system stays in equilibrium,

From classical thermodynamics it is known that

Here Sα is the molar entropy (entropy per mole) of phase α and Vα is the molar volume (volume of one mole) of this phase. It follows that

From the second law of thermodynamics it is known that for a reversible phase transition it holds that

where Q is the amount of heat necessary to convert one mole of compound from phase I into phase II. Elimination of the entropy and taking the limit of infinitesimally small changes in T and P gives the Clausius-Clapeyron equation,

Approximate solution

The Clausius-Clapeyron equation is exact. When we make the following assumptions we may perform the integration:

- The molar volume of phase I is negligible compared to the molar volume of phase II: VII >> VI. In general, far from the critical point, this inequality holds well for liquid-gas transitions.

- Phase II satisfies the ideal gas law

- If phase II is a gas and the pressure is fairly low this assumption is reasonable.

- The transition heat Q is constant over the temperature integration interval. The integrations run from the lower temperature T1 to the upper temperature T2 and from P1 to P2.

Under these condition the Clausius-Clapeyron equation becomes

Integration gives

where ln is the natural (base e) logarithm. We reiterate that for gas-liquid transitions Q is the heat of vaporization.