Polar coordinates: Difference between revisions

imported>Paul Wormer No edit summary |

imported>Paul Wormer (Rewrite of lead-in: start with classical definition) |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

::''For an extension to three dimensions, see [[spherical polar coordinates]].'' | |||

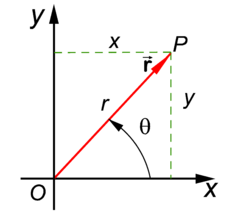

[[Image: Polar coordinates .png|right|thumb|250px|Two dimensional polar coordinates ''r'' and θ of vector <math>\scriptstyle \vec{\mathbf{r}}</math>]] | [[Image: Polar coordinates .png|right|thumb|250px|Two dimensional polar coordinates ''r'' and θ of vector <math>\scriptstyle \vec{\mathbf{r}}</math>]] | ||

In [[mathematics]] and [[physics]], '''polar coordinates''' give the position of a vector | |||

== | In [[mathematics]] and [[physics]], '''polar coordinates''' are two numbers—a distance and an angle—that specify the position of a point on a plane. | ||

The polar coordinates are related to the [[Cartesian coordinates]] ''x'' and ''y'' through | |||

In their classical ("pre-vector") definition polar coordinates give the position of a point ''P'' with respect to a given point ''O'' (the ''pole'') and a given line (the ''polar axis'') through ''O''. One real number (''r'' ) gives the distance of ''P'' to ''O'' and another number (θ) gives the angle of the line ''O''—''P'' with the polar axis. Given ''r'' and θ, one determines ''P'' by constructing a circle of radius ''r'' with ''O'' as origin, and a line with angle θ measured counterclockwise from the polar axis. The point ''P'' is on the intersection of the circle and the line. | |||

In modern vector language one identifies the plane with a real Euclidean space <math>\scriptstyle \mathbb{R}^2</math> that has a [[Cartesian coordinate]] system. The crossing of the Cartesian axes is on the pole, that is, ''O'' is the origin of the Cartesian system and the polar axis is identified with the ''x''-axis of the Cartesian system. The line ''O''—''P'' is generated by the vector | |||

:<math> | |||

\overrightarrow{OP} \equiv \vec{\mathbf{r}}. | |||

</math> | |||

Hence we obtain the figure on the right where <math>\scriptstyle \vec{\mathbf{r}}</math> is the position vector of the point ''P''. | |||

==Algebraic definition== | |||

The polar coordinates ''r'' and θ are related to the [[Cartesian coordinates]] ''x'' and ''y'' through | |||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

\begin{align} | \begin{align} | ||

| Line 19: | Line 33: | ||

\end{cases} | \end{cases} | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Bounds on the coordinates are: ''r'' ≥ 0 and 0 ≤ θ < 360<sup>0</sup>. | |||

Coordinate lines are: the circle (fixed ''r'', all θ) and a half-line from the origin (fixed direction θ all ''r''). The [[slope]] of the half-line is tanθ = ''y''/''x''. | |||

==Surface element== | ==Surface element== | ||

The infinitesimal surface element in polar coordinates is | The infinitesimal surface element in polar coordinates is | ||

| Line 30: | Line 46: | ||

\cos\theta & -r\sin\theta \\ | \cos\theta & -r\sin\theta \\ | ||

\sin\theta & r\cos\theta \\ | \sin\theta & r\cos\theta \\ | ||

\end{vmatrix} | \end{vmatrix} = r \cos^2\theta + r^2\sin^2\theta | ||

= r . | = r . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Example: the area ''A'' of a circle of radius ''R'' is given by | Example: the area ''A'' of a circle of radius ''R'' is given by | ||

:<math> | :<math> | ||

A = \int_{0}^{2\pi} \int_{0}^R r\, dr\, d\theta = \pi R^2 | A = \int_{0}^{2\pi} \int_{0}^R r\, dr\, d\theta = \pi R^2 . | ||

</math> | </math> | ||

Revision as of 07:38, 23 January 2008

- For an extension to three dimensions, see spherical polar coordinates.

In mathematics and physics, polar coordinates are two numbers—a distance and an angle—that specify the position of a point on a plane.

In their classical ("pre-vector") definition polar coordinates give the position of a point P with respect to a given point O (the pole) and a given line (the polar axis) through O. One real number (r ) gives the distance of P to O and another number (θ) gives the angle of the line O—P with the polar axis. Given r and θ, one determines P by constructing a circle of radius r with O as origin, and a line with angle θ measured counterclockwise from the polar axis. The point P is on the intersection of the circle and the line.

In modern vector language one identifies the plane with a real Euclidean space that has a Cartesian coordinate system. The crossing of the Cartesian axes is on the pole, that is, O is the origin of the Cartesian system and the polar axis is identified with the x-axis of the Cartesian system. The line O—P is generated by the vector

Hence we obtain the figure on the right where is the position vector of the point P.

Algebraic definition

The polar coordinates r and θ are related to the Cartesian coordinates x and y through

so that for r ≠ 0,

Bounds on the coordinates are: r ≥ 0 and 0 ≤ θ < 3600. Coordinate lines are: the circle (fixed r, all θ) and a half-line from the origin (fixed direction θ all r). The slope of the half-line is tanθ = y/x.

Surface element

The infinitesimal surface element in polar coordinates is

The Jacobian J is the determinant

Example: the area A of a circle of radius R is given by