Vietnam War: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

||

| Line 162: | Line 162: | ||

==South Vietnamese government== | ==South Vietnamese government== | ||

{{main|Government of the Republic of Vietnam}} | {{main|Government of the Republic of Vietnam}} | ||

There was a gradual transition from overt military government to at least the appearance of democratic government, but South Vietnam neither developed a true popular government, nor rooted out the corruption that caused a lack of support. | After the French colonial authority ended, there was a nominally civilian government, first under [[Bao Dai]] and then [[Ngo Dinh Diem]], who ruled from 1954 to 1963, neither of which were elected. Diem was eventually overthrown and killed in a military coup. There was a gradual transition from overt military government to at least the appearance of democratic government, but South Vietnam neither developed a true popular government, nor rooted out the corruption that caused a lack of support. After the Diem coup in November 1963, for example, there was a nominal civilian government really under military control, which was overthrown by yet another military group in January 1964. Some of the same generals were in both the November and January coups. | ||

Power constantly shifted in 1964 to 1967. This was not, as some have suggested, purely a series of struggles among military juntas. There were multiple Buddhist and other factions competing from outside the government. [[William Colby]], then chief of the [[Central Intelligence Agency]] Far Eastern Division, observed that civilian politicians "divided and sub-divided into a tangle of contesting ambititions and claims and claims to power and participation in the government."<ref>William Colby, ''Lost Victory'', 1989, p. 173, quoted in McMaster, p. 165</ref> Some of these contests were simple drives for political power or wealth, while other reflected feeling of seeking to avoid preference for some groups, Catholic vs. Buddhist in the Diem Coup. Not all the competing groups, such as the Buddhists, were monolithic, and had their own internal struggles. | Power constantly shifted in 1964 to 1967. This was not, as some have suggested, purely a series of struggles among military juntas. There were multiple Buddhist and other factions competing from outside the government. [[William Colby]], then chief of the [[Central Intelligence Agency]] Far Eastern Division, observed that civilian politicians "divided and sub-divided into a tangle of contesting ambititions and claims and claims to power and participation in the government."<ref>William Colby, ''Lost Victory'', 1989, p. 173, quoted in McMaster, p. 165</ref> Some of these contests were simple drives for political power or wealth, while other reflected feeling of seeking to avoid preference for some groups, Catholic vs. Buddhist in the Diem Coup. | ||

Not all the competing groups, such as the [[Vientamese Buddhism|Buddhists]], were monolithic, and had their own internal struggles. There were a number of groups, often derived from religious sects, which became involved in the jockeying for political power, such as the [[Cao Dai]] and [[Hoa Hao]]. At varying times, sects, organized crime such as the [[Binh Xuyen]], and individual provincial leaders had paramilitary groups that affected the political process. The [[Montagnard]] ethnic groups wanted substantial autonomy. | |||

Vietnamese and U.S. goals were also not always in complete agreement. Certainly up to 1969, the U.S. was generally anything opposed to any policy, nationalist or not, which might lead to the South Vietnamese becoming neutralist rather than anticommunist. The Cold War [[containment]] policy was in force through the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Administrations, while the Nixon administration was supportive of a more multipolar model of [[detente]]. | Vietnamese and U.S. goals were also not always in complete agreement. Certainly up to 1969, the U.S. was generally anything opposed to any policy, nationalist or not, which might lead to the South Vietnamese becoming neutralist rather than anticommunist. The Cold War [[containment]] policy was in force through the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Administrations, while the Nixon administration was supportive of a more multipolar model of [[detente]]. | ||

Revision as of 14:07, 13 December 2008

Template:TOC-right Since there is a current state and government of Vietnam, with full diplomatic representation including participation in international organizations, the final authorities on the definition of Vietnam War would appear to be the Vietnamese. They tend to refer to the Wars (plural) of Vietnam, often referring to a period starting sometime after 1959 and extending to 1975 as the "American War". Considering actions in Laos and Cambodia also confuse the terminology; not all the fighting there bore directly on Vietnam or French Indochina.

Without trying to name the wars, the key timeline events in modern history are:

- 1858-1862: French invasion and establishment of colonial government

- 1941: Japanese invasion of French Indochina

- 1945: End of World War II and return of Indochina to French authority; formal resistance starts circa 1946.

- 1954: End of French control and beginning of partition under the Geneva agreement; CIA covert operation started

- 1955: First overt U.S. advisers sent to the South

- 1959: North Vietnamese policy decision, in May 1959 to create the 559th (honoring the date) Transportation Group and begin covert infiltration of the South

- 1961: U.S. advisory support begins to extend to tactical movement and fire support

- 1964: Gulf of Tonkin incident and start of U.S. ground combat involvement; U.S. advisors and support, as well as covert operations, had been in place for several years

- 1969: Vietnamization policy starts

- 1972: South Vietnamese take over ground combat responsibility Withdrawal of last U.S. combat forces as a result of negotiation

- 1975: Overthrow of the Southern government by regular Northern troops, followed by reunification under a Communist government.

While some see a period in which fighting in Southeast Asia merely was a proxy for what many Westerners believe was an existential battle between Western and Communist ideology, this is a view external to that of Vietnam. The wars between 1946 and 1975, however, were clearly existential for the Vietnamese. Moyar, quoting Fredrik Logevall, writes of a "orthodox-revisionist split" about it being "axiomatic" that the U.S. was wrong to go to war in Vietnam, and suggests that the revisionist position is that the U.S. had a rational Cold War policy in committing to fight in Vietnam. [1] This ignores, however, the reality that whether their motivations were world-communist or purely nationalist, the Vietnamese were fighting. If this article were solely about the U.S. involvement in Vietnam, the argument might be compelling. It is, however, a trap to assume that the wars of Vietnam, beginning before Europeans set foot on the North American continent, are somehow dependent on the U.S. The U.S. involvement, of course, does involve the U.S., and there are subarticles here that deal specifically with that involvement.

Vietnamese drives for independence begin, at least, in the 1st century C.E., with the Trung Sisters' revolt against the Chinese; the citation here mentions the 1968th anniversary of their actions.[2] It cannot be strongly enough emphasized that the Vietnamese, as a people, live in a context of millenia of war. Individuals may have been fighting for decades, with no resolution in sight.

A useful perspective comes from retired U.S. lieutenant general Harold G. Moore (U.S. Army, retired) and journalist Joseph L. Galloway. Their book, We Were Soldiers once, and Young, as well as the movie made about the subject, part of the Battle of the Ia Drang, has been iconic, to many, of the American involvement. [3] Recently, they returned to their old battlefields and met with their old enemies, both sides seeking some closure. Some of their perspective may help.

Perspective and Naming

In 1990, one of their visits included the Vietnam Historic Museum in Hanoi.

The high point for us was not the exhibits but finding a huge mural that was both a timeline and a map of Vietnam's unhappy history dating back well over a thousand years...the Chinese section of the timeline stretched out for fifty feet or so. The section devoted to the French and their 150 years of colonial occupation was depicted in about twelve inches. The minuscule part that marked the U.S. war was only a couple of inches.[4]

So, while War in Vietnam goes back to to the rebellion, against China, of the Trung Sisters in the first century C.E., practical limits need to be set on the scope of this article. Many other articles can deal with other aspects, of the long history of Vietnam, than the period roughly from 1941 to 1975, all or part of which seems to form the Western concept of the Vietnam War.

From a Western concept that all post-WWII matters centered around Communism, it was the military effort of the Communist Party of Vietnam under Ho Chi Minh to defeat France (1946-54), and the same party (by changing names), then in control of North Vietnam, to overthrow the government of South Vietnam (1958-75) and take control of the whole country, in the face of military intervention by the United States (1964-72). Vo Nguyen Giap speaks of the Resistance War starting on December 19, 1946, and ending with the French exist.[5] Communists also use the term American War, although the dates are less clearly defined.

Others discuss the Viet Minh resistance, in the colonial period, to the French and Japanese, and the successful Communist-backed overthrow of the post-partition southern government, as separate wars. Unfortunately for naming convenience, there is a gap between the end of French rule and the start of partition in 1954, and the Northern decision to commit to controlling the South in 1959. It also must be noted that there was a deliberate delay, for building up infrastructure, from that 1959 decision and the actual intensification of combat.

Background

There are important background details variously dealing with the start of French colonization in Indochina, including the present countries of Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos. Vichy French cooperation in ruling Indochina and a Japanese presence in 1941 triggered U.S. export embargoes to Japan, which affected the Japanese decision to attack Western countries in December 1941; see Vietnam, war, and the United States .

In the West, the term is usually considered to have begun somewhere in the mid-20th century. There were at least two periods of hot war, first the Vietnamese war of independence from the French, including guerilla resistance starting during the Second World War and ending in a 1954 Geneva treaty that partitioned the country into the Communist North (NVN) (Democratic Republic of Vietnam, DRV) and non-Communist South (SVN) (Republic of Vietnam, RVN). A referendum on reunification had been scheduled for 1956, but never took place. Nevertheless, a complex and powerful United States Mission to the Republic of Vietnam was always present after the French had left and the Republic of Vietnam established.

While Communists had long had aims to control Vietnam, the specific decision to conquer the South was made, by the Northern leadership, in May 1959. The Communist side had clearly defined political objectives, and a grand strategy, involving military, diplomatic, covert action and psychological operations to achieve those objectives. Whether or not one agreed with those objectives, there was a clear relationship between long-term goals and short-term actions, within the theory of dau trinh.

Quite separate from its internal problems, South Vietnam faced an unusual military challenges. On the one hand, there was a threat of a conventional, cross-border strike from the North, reminiscent of the Korean War. In the fifties, the U.S. advisors focused on building a "mirror image" of the U.S. Army, designed to meet and defeat a conventional invasion. [6]

Diem (and his successors) were primarily interested in using the ARVN as a device to secure power, rather than as a tool to unify the nation and defeat its enemies. Province and District Chiefs in the rural areas were usually military officers, but reported to political leadership in Saigon rather than the military operational chain of command. The 1960 "Counterinsurgency Plan for Vietnam (CIP)" from the U.S. MAAG was a proposal to change what appeared to be a dysfunctional structure. [6]

Arguably, some of the later southern insurgency was more anti-Diem rather than pro-communist. After the overthrow of Diem, Cao Dai and other factions broke away from the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam; at least briefly, they regarded the absence of Diem as liberation. The hard-line Comunists, of course, disagreed.

Further analysis showed the situation was not only jockeying for power, but also reflected that the province chief indeed had security authority that could conflict with that of tactical military operations in progress, but also had responsibility for the civil administration of the province. That civil administration function became more and more intertwined, starting in 1964 and with acceleration in 1966, of the "other war" of rural development.[7]

In contrast, the Southern governments from 1954 did not either have popular support or tight control over the populace. There was much jockeying for power as well as corruption. An assumption here is that while the U.S. and other countries had major roles, the thrust of the article is how it affected Vietnam and the Vietnamese. Issues of U.S. politics and opinion that affected it are in Vietnam, war, and the United States.

After the Gulf of Tonkin incident, in which U.S. President Lyndon Baines Johnson claimed North Vietnamese naval vessels had attacked U.S. warships, open U.S. involvement began in 1964, and continued until 1972. After the U.S. withdrawal based on a treaty in Paris, the two halves were to be forcibly united, by DRV conventional invasion, in 1975. T-54 tanks that broke down the gates of the Presidential Palace in the southern capital, Saigon, were not driven by ragged guerrillas.

French Indochina Background

- See also: Vietnam, pre-colonial history

At the time of the French invasion, during the Second French Revolution with Louis Napoleon III as President, there were four parts of what is now Vietnam:

- Cochin China in the south, including the Mekong Delta and what was variously named Gia Dinh, Saigon, and Ho Chi Minh City

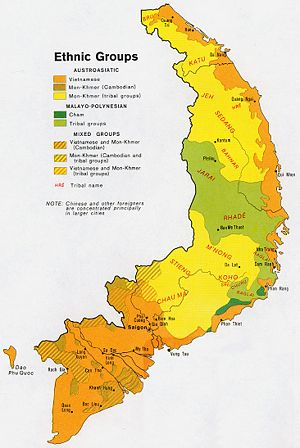

- Annam in the center, with the cultural capital of Hue; the mountainous Central Highlands, the home of the Montagnard peoples, considered itself autonomous

- Tonkin in the North, including the Red River Delta, Hanoi, and Haiphong.

In 1858, France invaded Vietnam, and the ruling Nguyen dynasty accepted protectorate status. Cambodia and Laos also came under French control. In June 1867, he seized the last provinces of Cochin China. The Siamese government, in July, agreed to the Cambodian protectorate in return for receiving the two Cambodian provinces of Angkor and Battambang, to Siam. Siam was never under French control. Napoleon III fell in 1870, and French colonial officers were freed to focus on expansion in Indochina. [8]

Indochina operated as a colony from this time up until 1945, with growing nationalist attempts at Indochinese revolution, accelerating after 1946. There were a variety of nationalist movements, non-Communist (e.g., Viet Nam Quoc Dan Dang) and Communist (e.g., Indochinese Communist Party; the Viet Minh became the dominant revolutionary force.

Indochina and the Second World War

In 1940 and 1941 the Vichy regime yielded control of Vietnam to the Japanese, and Ho returned to lead an underground independence movement (which received a little assistance from the O.S.S., the predecessor of the Central Intelligence Agency CIA).[9]

Indochina, a French colony in the spheres of influence of Japan and China, was destined to be drawn into the Second World War both through European and Asian events. From 1946 to 1948, the French reestablished control, but, in 1948, began to explore a provisional government. While there is no clear start to what ended in 1954, the more serious nationalist movement was clearly underway by 1948.

Indochinese revolution

While there is no universally agreed name for this period in the history of Vietnam, it is the period between the formation of a quasi-autonomous government within the French Union, and the the eventual armed defeat of the French colonial forces by the Viet Minh. That defeat led to the 1954 Geneva accords that split Vietnam into North and South.

The French first created a provisional government under Bao Dai, then recognized Vietnam as a state within the French Union. In such a status, France would still control the foreign and military policy of Vietnam, which was unacceptable to both Communist and non-Communist nationalists.

The Two Vietnams after Geneva

- See also: Government of the Republic of Vietnam

This period was begun by the military defeat of the French in 1954, with a Geneva meeting that partitioned Vietnam into North and South. Two provisions of the agreement never took place: a referendum on unification in 1956, and also banned foreign military support and intervention. Neither the Communist side nor the Diem government, for their own reasons, wanted the referendum to take place.

In the south, the Diem government was not popular, but there was no obvious alternative that would rise above factionalism, and also gain external support. Anti-Diem movements were not always Communist, although some certainly were. Diem himself, however, had his own authoritarian philosophy with mixed Confucian, French, and Vietnamese roots, and was not psychologically open to the idea of an opposition. Ho and the North probably would have won an election, but free elections were also alien concepts to them, and they wanted to keep overall control, not throw the dice on the reaction of the people.

The north was exploring its policy choices, both in terms of the south, and its relations with China and the Soviet Union. The priorities of the latter, just as U.S. and French priorities were not necessarily those of Diem, were not necessarily those of Ho. In 1959, North Vietnam made the explicit decision to overthrow the South by military means. Originally, the military means were guerilla warfare, carried out by the Viet Cong, or the military arm of the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF). While the eventual fall of South Vietnam would be due to conventional rather than guerilla warfare, some authors, such as Bui Tin, assert that the NLF was never an indigenous Southern force but always under the control of the North. [10]

Pacification

After partition, there was a continuing struggle for security of the rural population, and for gaining support from that populace for the government. A variety of terms were used to discuss the many programs involved, but a convenient general term is pacification in South Vietnam. It has also been called the "Other War" or "Second War" to differentiate it from direct combat with Communist military forces in the South, although some refer to a "Third War" against Communists outside the South.

There is little doubt that there was some kind of Viet Minh-derived "stay behind" organization betweeen 1954 and 1960, but it is unclear that they were directed to take over action until 1957 or later. Before that, they were unquestionably recruiting and building infrastructure, a basic first step in a Maoist protracted war mode.

While the visible guerilla incidents increased gradually, the key policy decisions by the North were made in 1959. Early in this period, there was a greater degree of conflict in Laos than in South Vietnam. U.S. combat involvement was, at first, greater in Laos, but the activity of advisors, and increasingly U.S. direct support to South Vietnamese soldiers, increased, under U.S. military authority, in late 1959 and early 1960. Communications intercepts in 1959, for example, confirmed the start of the Ho Chi Minh trail and other preparation for large-scale fighting.

Specific programs included the Strategic Hamlet Program, Revolutionary Development, the U.S. Marine Combined Action Platoon program, and others.

U.S. support to South Vietnam before Gulf of Tonkin

To put the situation in a strategic perspective, remember that North and South Vietnam were artificial constructs of the 1954 Geneva agreements. While there had been several regions of Vietnam, when roughly a million northerners, of different religion and ethnicity than in the south, migrated into a population of five to ten million, there were identity conflicts. Communism has been called a secular religion, and the North Vietnamese government officials responsible for psychological warfare, as well as military operations, were part of a system of cadre. Communism, for its converts, was an organizing belief system that had no equivalent in the South. At best, the southern leadership intended to have a prosperous nation, although leaders were all too often focused on personal prosperity. Their Communist counterparts, however, had a mission of conversion by the sword — or the AK-47 assault rifle.

Between the 1954 Geneva accords and 1956, the two countries were still forming; the influence of major powers, especially France and the United States, and to a lesser extent China and the Soviet Union, were as much an influence as any internal matters. There is little question that in 1957-1958, there was a definite early guerilla movement against the Diem government, involving individual assassinations, expropriations, recruiting, shadow government, and other things characteristic of Mao's Phase I. The actual insurgents, however, were primarily native to the south or had been there for some time. While there was clearly communications and perhaps arms supply from the north, there is little evidence of any Northern units in the South, although organizers may well have infiltrated.

It is clear there was insurgency in the South from after the French defeat to the North Vietnamese decision to invade, but it is far more difficult to judge when and if the insurgency was clearly directed by the North. Given the two national sides both operated on the principle that their citizens were for them or against them, it is difficult to know how much neutralist opinion might actually have existed.

Guerilla attacks increased in the early 1960s, at the same time as the new John F. Kennedy administration made Presidential decisions to increase its influence. Diem, as other powers were deciding their policies, was clearly facing disorganized attacks and internal political dissent. There were unquestioned conflicts between the government, dominated by minority Northern Catholics, and both the majority Buddhists and minorities such as the Montagnards, Cao Dai, and Hoa Hao. These conflicts were exploited, initially at the level of propaganda and recruiting, by stay-behind Viet Minh receiving orders from the North

Gulf of Tonkin incident

President Johnson asked for, and received, Congressional authority to use military force in Vietnam after the Gulf of Tonkin incident, which was described as a North Vietnamese attack on U.S. warships. After much declassification and study, much of the incident remains shrouded in what Clausewitz called the "fog of war", but serious questions have been raised of whether the North Vietnamese believed they were under attack, who fired the first shots, and, indeed, if there was a true attack. Congress did not declare war, which is defined as its responsibility in the Constitution of the United States; nevertheless, it launched what effectively was the longest war in U.S. history -- and even longer if the covert actions before the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin situation is considered.

The Gulf of Tonkin resolution, although later revoked, was considered, by Lyndon Johnson, his basic authority to conduct military operations in Southeast Asia. It was another example of how declarations of war have become extremely rare following the Second World War.

South Vietnamese government

After the French colonial authority ended, there was a nominally civilian government, first under Bao Dai and then Ngo Dinh Diem, who ruled from 1954 to 1963, neither of which were elected. Diem was eventually overthrown and killed in a military coup. There was a gradual transition from overt military government to at least the appearance of democratic government, but South Vietnam neither developed a true popular government, nor rooted out the corruption that caused a lack of support. After the Diem coup in November 1963, for example, there was a nominal civilian government really under military control, which was overthrown by yet another military group in January 1964. Some of the same generals were in both the November and January coups.

Power constantly shifted in 1964 to 1967. This was not, as some have suggested, purely a series of struggles among military juntas. There were multiple Buddhist and other factions competing from outside the government. William Colby, then chief of the Central Intelligence Agency Far Eastern Division, observed that civilian politicians "divided and sub-divided into a tangle of contesting ambititions and claims and claims to power and participation in the government."[11] Some of these contests were simple drives for political power or wealth, while other reflected feeling of seeking to avoid preference for some groups, Catholic vs. Buddhist in the Diem Coup.

Not all the competing groups, such as the Buddhists, were monolithic, and had their own internal struggles. There were a number of groups, often derived from religious sects, which became involved in the jockeying for political power, such as the Cao Dai and Hoa Hao. At varying times, sects, organized crime such as the Binh Xuyen, and individual provincial leaders had paramilitary groups that affected the political process. The Montagnard ethnic groups wanted substantial autonomy.

Vietnamese and U.S. goals were also not always in complete agreement. Certainly up to 1969, the U.S. was generally anything opposed to any policy, nationalist or not, which might lead to the South Vietnamese becoming neutralist rather than anticommunist. The Cold War containment policy was in force through the Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson Administrations, while the Nixon administration was supportive of a more multipolar model of detente.

While there were still power struggles and internal corruption, there was much more stability between 1967 and 1975. Still, the South Vietnamese government did not enjoy either widespread popular support, or even an enforced social model of a Communist state. It is much easier to disrupt a state without common popular or decisionmaker goals.

U.S. policy

This section focuses on those parts of the U.S. political system, which either set an overall U.S. foreign policy, or were principally directed at another audience than in the U.S. George Kennan, considered a consummate diplomat and diplomatic theorist, observed that American leaders, starting with the 1899-1900 "Open Door" policy to China, have a

neurotic self-consciousness and introversion, the tendency to make statements and take actions with regard not to their effect on the international scene byt rather to their effect on those echelons of American opinion, congressional opinion first and foremost, to which the respect statesmen are anxious to appeal. The question became not: How effective is what I am doing in terms of the impact it makes on our world environment? but rather: how do I look, in the mirror of American domestic opinon, as I do it?[12]

Even though the leaders' goals might be totally sincere, that need to be seen as doing the popular thing can become counterproductive. There were many times, in the seemingly inexorable advance of decades of American involvement in Southeast Asia, where reflection might have led to caution. Instead, the need to be seen as active, as well as the clashes of strong egos, separate the needs of policy from the dictates of politics.

The line is sometimes hard to draw, but the pure U.S. political, as much as possible, is in Vietnam, war, and the United States, and the policy in the main article and its Vietnam-specific subaricles. Sometimes, an issue needs to be in both: for example, a possible peace offer through Robert F. Kennedy (RFK) is at least summarized in the main Vietnam War article, but the personal dynamics between RFK and Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) are in the Vietnam, war, and the United States.

The greatest U.S. involvement was from mid-1964 through 1972, with some activity on both ends. So, a good deal of the detailed U.S. political action with other countries will be in Joint warfare in South Vietnam 1964-1968, Vietnamization, and air operations against North Vietnam. It is not practical to draw a hard-and-fast line. Many, but by no means all, of the key political decisions were under Johnson, but Presidents from Truman through Ford all had roles.

Although the combination of the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and the political authority granted to Lyndon Johnson by being elected to the presidency rather than succeeding to it gave him more influence, and there was certainly an immense infusion of U.S. and allied forces into the theater of operations, never forget the chief participants in the war were Vietnamese.

Truman and Eisenhower legacy

Truman, on taking office, said he felt as if the moon and stars had landed on him, and one can be sympathetic. He had not been in the inner circles of a mythic President, but immediately was faced with immense decisions. As soon as the war ended, he was under great pressure to return the country to normal civilian conditions; the electorate, much as the British electorate rejected Winston Churchill as the European war ended, wanted a peacetime look.

There were no such pressures to demobilize, however, on Josef Stalin and Mao Tse Tung. There was much blame for "losing" Eastern Europe and China, but it is less clear what could have been done to stop it. Certainly, the pressure to cut military commitment came home to roost in the Korean War, when Truman had few forces to dispatch.

Eisenhower was able to capitalize on the perceived losses under Truman, and formulate a strong policy of containing Communism. John Foster Dulles was its most visible advocate, supported, inside the establishment, by his brother Allen Dulles, director of the Central Intelligence Agency. Eisenhower's background generally gave him great confidence in dealing with military hard-liners such as Admiral Arthur Radford, the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff who wanted to intervene at Dien Bien Phu. Eisenhower would listen to the Chiefs, and be decisive, while the Kennedy administration would hold them at arms' length.

John F. Kennedy (JFK) administration

Its term for itself, the "New Frontier", was superficially apt; JFK saw himself in a transformational role. . Its rougher operatives had a different style than Joe McCarthy, although it is sometimes forgotten that Robert Kennedy (RFK) had been on McCarthy's staff. [13]

While he, and his key staff, came from an elite, it was from a different elite than that which had spawned John Foster Dulles. Even though the Sino-Soviet split was evident by 1961, the assumption of monolithic Communism was not really examined on the road to involvement in Southeast Asia. While the form was different, a militant anti-Communism was underneath many of the Administration policies. [14]

Where Republicans during the Truman and Eisenhower administrations blamed Democrats who had "lost China", the Kennedy Administration was not out to lose anything, but to win. When Fidel Castro took control of Cuba, the Eisenhower Administration broke diplomatic relations and began studying destabilization, the Kennedy administration did not intend merely to study.

Kennedy was fascinated by special operations forces, far more than had been Eisenhower, the commander of vast conventional armies. JFK is remembered as the patron of United States Army Special Forces.[15] While the first covert operatives went into Laos under Eisenhower, the involvement escalated under Kennedy.

It is not unfair to say that Lyndon Johnson and Robert Kennedy (RFK) despised one another, which began in the JFK administration and grew worse over time. In February 1967, the situation grew worse as a possible peace feeler was assumed, incorrectly, as leaked by Kennedy, and that Kennedy increasingly positioned himself as the 1968 Democratic Party peace candidate, portraying Johnson as a warmonger.

Lyndon Baines Johnson (LBJ) administration

Johnson's motives were different from Kennedy's, just as Nixon's motivations would be different from Johnson's. Of the three, Johnson was most concerned with U.S. domestic policy. He probably did want to see improvements in the life of the Vietnamese, but the opinions of his electorate were most important. His chief goal was implementing the set of domestic programs that he called the "Great Society". He judged actions in Vietnam not only on their own merits, but how they would be perceived in the U.S. political system. [16] To Johnson, Vietnam was a "political war" only in the sense of U.S. domestic politics, not a political settlement for the Vietnamese. He also saw it political in the sense of both his personal, and the U.S., position vis-a-vis the reso of the world.

Johnson and McNamara directed a three-part strategy, the first two developed by the civilian policymakers in Washington, and the third selected by them from different concepts by American leaders in Vietnam. Note that the initiative was coming from Johnson; the admittedly unstable South Vietnamese government was not part of defining their national destiny.

Of several alternatives for stabilizing the South, Johnson chose the plan advocated by GEN William Westmoreland as most likely to succeed in the relatively near term. By 1968, and perhaps in 1967, Johnson's chief adviser on the war, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, had increasingly less faith in the Johnson-Westmoreland model. McNamara quotes GEN William DuPuy, Westmoreland's chief planner, as recognizing that as long as the enemy could fight from the sanctuaries of Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam, it was impossible to bring adequate destruction on the enemy, and the model was inherently flawed.[17]

Also fundamental to Johnson was protecting his domestic legacy. Karnow quotes his comment to his biographer, Doris Kearns, as

I knew from the start that I was bound to be crucified either way I moved. If I left the woman I really loved — the Great Society — in order to get invoved with that bitch of a war on the other side of the world, then i would lose everything at home. All my programs. All my hopes to feed the hungry and shelter the homeess. All my dreams to provide education and medical care to the browns and the blacks and the lame and the poor. But if I left that war and let the Communists take over South Vietnam, I would be seen as a coward and my nation seen as an apeaser, and we would both find it impossible to accomplish anything for anybody anywhere on the entire globe.[18]

See also Vietnam, war, and the United States for Johnson's belief of how a loss of South Vietnam would trigger domestic political attacks from right-wing ideologues that considered him the greatest of the dominoes.

McNamara, who had been appointed by Kennedy, continued to push an economic and signaling grand strategy to Johnson. Johnson and McNamara, although it would be hard to find two men of more different personality, formed a quick bond. McNamara appeared more impressed by economics and Schelling's compellence theory [19] than by Johnson's liberalism or Senate-style deal-making, but they agreed in broad policy. [20]

Johnson and politics

Johnson, above all, focused on domestic politics. As part of that, he did not want to be criticized as a president who had "lost" Vietnam.

His personality was quite different than those of key JFK advisers, but he formed close bonds with some. Above all, he was comfortable with Robert McNamara, JFK's Secretary of Defense; Dean Rusk, Secretary of State] under JFK, and McGeorge Bundy, Assistant to the Secretary for National Security Affairs.

Opposition against him peaked in a period often called "Tet". While "Tet" is convenient shorthand, it was actually part of a North Vietnamese strategy targeted against U.S. opinion. Militarily, it began with a series of attacks in September 1967, notably the Battle of Con Thien, followed by the Battle of Dak To and the Battle of Khe Sanh. These drew Westmoreland's attention from the secret preparation for attacks on cities, where Giap equally misread the strategic implications; there is widespread belief he expected attacks on the cities to lead to the General Uprising.

On March 31, 1968, Johnson said on national television,

I shall not seek, and I will not accept, the nomination of my party for another term as your president

Bombing halt and peace talks

In March, Johnson had also announced a bombing halt, in the interests of starting talks. The first discussions were limited to starting broader talks, as a quid-pro-quo for a bombing halt. Johnson agreed to stop bombing North Vietnam proper, although he would continue reconnaissance over the North and bombing of the Ho Chi Minh trail, and, of course, in South Vietnam. According to Kissinger, there also was an "understanding", never formally confirmed by the North but to which it did not object, that there would be:[21]

- No attacks on major cities

- No artillery fire from or across the Demilitarized Zone

- No threatening troop movements in or near the DMZ, which would suggest movement into the South

The first meeting was on 10 May, with the delegations headed by Xuan Thuy, North Vietnamese foreign minister, and ambassador-at-large Averell Harriman. The main discussions were outside the conference room, where there continued to be symbolic arguments about status, and even of the shape of the table, by the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, South Vietnam) and the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam (NLF, Viet Cong).

Without the participation of the RVN, it was difficult to conceive of serious negotations, unless one accepted the North Vietnamese claim that the RVN was a total puppet of the U.S. Given the constant friction between the RVN and U.S., this seemed less than plausible. The North's additional demand to include the NLF as an equal party also delegitimized the RVN, something utterly unacceptable to Thieu.

Two days after the start, the Communist position was that substantive talks could begin only with the total and unconditional withdrawal of U.S. forces, coupled with an overthrow of the RVN. In practice, this led to continued four-way posturing that accomplished little, while secret talks continued between the US and DRV.

Richard M. Nixon (RMN) administration

- See also: Vietnam, war, and the United States with special emphasis on the change of basic U.S. policy from containment to detente, and domestic opinion about the war

- See also: Air operations against North Vietnam

- See also: Air campaigns against Cambodia and Laos

Prior to the presidential election, Johnson had announced a bombing halt on October 31, 1964, in he interest of opening dialogue. During the campaign, a random wire service story headlined that Nixon had a "secret plan for ending the war, but, in reality, Nixon was only considering alternatives at this point. He remembered how Eisenhower had deliberately leaked, to the Communist side in the Korean War, that he might be considering using nuclear weapons to break the deadlock. Nixon adapted this into what he termed the "Madman Strategy".[22]

He told H.R. Haldeman, one of his closest aides,

I call it the madman theory, Bob.I want the North Vietnamese to believe that I've reached the point that I might do anything to stop the war. We'll just slip the word to them that for God's sake, you know Nixon is obsessed about communism. We can't restrain him when he's angry, and he has his hand on the nuclear button, and Ho Chi Minh himself will be in Paris in two days begging for peace.[23]

Policy review

After the election of Richard M. Nixon, a review of U.S. policy in Vietnam was the first item on the national security agenda. Henry Kissinger, the Assistant to the President for National Security Affairs, asked all relevant agencies to respond with their assessment, which they did on March 14, 1969.[24]

Immediate action

While Nixon hesitated to authorize a military request for bombing Cambodian sanctuaries, which civilian analysts considered less important than Laos, he authorized, in March, bombing of Cambodia as a signal to the North Vietnamese. While direct attack against North Vietnam, as was later done in Operation LINEBACKER I, might be more effective, he authorized the Operation MENU bombing of Cambodia, starting on March 17. These bombings were kept secret from the U.S. leadership and electorate; the North Vietnamese clearly knew hey were being bombed. It first leaked into the press in May, and Nixon ordered warrantless surveillance of key staff. [25]

Nixon also directed Cyrus Vance to to to Moscow in March, to encourage the Soviets to put pressure on the North Vietnamese to open negotiations with the U.S. [26] The Soviets, however, either did not want to get in the middle, or had insufficient leverage on the North Vietnamese.

Vietnamization

U.S. policy changed to one of turning ground combat over to South Vietnam, a process called Vietnamization, a term coined in Janaury 1969. Nixon, in contrast, saw resolution not just in Indochina, in a wider scope. He sought Soviet support, saying that if the Soviet Union helped bring the war to an honorable conclusion, the U.S. would "do something dramatic" to improve U.S.-Soviet relations. [21] In worldwide terms, Vietnamization replaced the earlier containment policy[27] with detente.[28]

Nuclear brinksmanship

In October 1969, Nixon began to explore nuclear options,[29] with the intent of pressuring North Vietnam and the Soviet Union.

Gerald R. Ford administration

While Ford, Nixon's final vice-president, succeeded Nixon, most major policies had been set by the time he took office. He was under a firm Congressional and public mandate to withdraw.

Allied ground troops depart

In the transition to full "Vietnamization," U.S. and third country ground troops turned ground combat responsibility to the Army of the Republic of Vietnam. Air and naval combat, combat support, and combat service support from the U.S. continued.

There were two unprecedented bombing campaigns. To stop the logistical support of the Eastertide invasion, Nixon launched Operation LINEBACKER I, which had the operational goal of disabling the infrastructure of infiltration.

When the North refused to return to negotiations in late in 1972, Nixon, in mid-December, ordered bombing at an unprecedented level of intensity, Operation LINEBACKER II. This was at the strategic and grand strategic levels, not so much attacking the infiltration infrastructure, but North Vietnam's physical ability to import supplies, its internal transportation and logistics, command and control, and integrated air defense system. Within one month of the start of the operation, a peace agreement was signed.

Peace accords and invasion, 1973-75

- Paris Peace Talks [r]: Secret bilateral talks between the U.S. and North Vietnam (1969-1973) to end U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War, resulting in the Paris Accords signed on January 28, 1973. [e]

- Fall of South Vietnam [r]: The result of a series of conventional military actions by the People's Army of Viet Nam, under the direction of the Politburo of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam, which led to the dissolution of the Republic of Vietnam and the reunification of North and South Vietnam into the Socialist Republic of Vietnam [e]

Peace accords were finally signed on 27 January 1973, in Paris. U.S combat troops immediately began withdrawal, and prisoners of war were repatriated. U.S. supplies and limited advise could continue. In theory, North Vietnam would not reinforce it troops in the south. The North, badly damaged by the bombings of 1972, recovered quickly and remained committed to the destruction of its rival. There was little U.S. popular support for new combat involvement, and no Congressional authorizations to expend funds to do so.

North Vietnam, by its own statement, launched a new conventional invasion in 1975 and seized Saigon on April 30.[30]

No American combat units were present until the final days, when Operation FREQUENT WIND was launched to evacuate Americans and 5600 senior Vietnamese government and military officials, and employees of the U.S. The 9th Marine Amphibious Brigade, under the tactical commmand of Alfred M. Gray, Jr., would enter Saigon to evacuate the last Americans from the American Embassy to ships of the Seventh Fleet. Ambassador Graham Martin was among the last civilians to leave. [31] In parallel, Operation EAGLE PULL evacuated U.S. and friendly personnel from Phnom Penh, Cambodia, on April 12, 1975, under the protection of the 31st Marine Amphibious Unit, part of III MAF.

Vietnam was unified under Communist rule, as nearly a million refugees escaped by boat. Saigon was renamed Ho Chi Minh City.

References

- ↑ Moyar, Mark (2006), Triumph Forsaken, Cambridge University Press, p. xii

- ↑ "Ha Noi celebrates Trung sisters 1,968th anniversary", Viet Nam News, 14 March 2008

- ↑ Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (1999), We were Soldiers Once...and Young: Ia Drang - the Battle That Changed the War in Vietnam, Random House

- ↑ Moore, Harold G. (Hal) & Joseph L. Galloway (2008), We are soldiers still: a journey back to the battlefields of Vietnam, Harper Collins

- ↑ Vo Nguyen Giap (1962), People's war, People's Army, Praeger, p. 88

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 , Chapter 6, "The Advisory Build-Up, 1961-1967," Section 1, pp. 408-457, The Pentagon Papers, Gravel Edition, Volume 2

- ↑ Eckhardt, George S. (1991), Vietnam Studies: Command and Control 1950-1969, Center for Military History, U.S. Department of the Army, pp. 68-71

- ↑ Karnow, Stanley (1983), Vietnam, a History, Viking Press, p. 79

- ↑ Patti, Archimedes L. A (1980). Why Viet Nam? Prelude to America's Albatross. University of California Press. , p. 477

- ↑ Bui Tin (2006), Fight for the Long Haul: the War as seen by a Soldier in the People's Army of Vietnam, in Wiest, Andrew, Rolling Thunder in a Gentle Land: the Vietnam War Revisited, Osprey Publishing, p. 55

- ↑ William Colby, Lost Victory, 1989, p. 173, quoted in McMaster, p. 165

- ↑ Kennan, George F. (1967), Memoirs 1925-1950, Little, Brown, pp. 53-54

- ↑ Thomas, Evan (October 2000), "Bobby: Good, Bad, And In Between - Robert F. Kennedy", Washington Monthly

- ↑ Halberstam, David (1972), The Best and the Brightest, Random House, pp. 121-122}}

- ↑ Halberstam, pp. 123-124

- ↑ McMaster, H.R. (1997), Dereliction of Duty : Johnson, McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam, HarperCollins, ISBN 0060187956

- ↑ Gen. William E Dupuy, August 1, 1988 interview, quoted by McNamara, pages 212 and 371.

- ↑ Doris Kearns and Merle Miller, quoted in Karnow, p. 320

- ↑ Carlson, Justin, "The Failure of Coercive Diplomacy: Strategy Assessment for the 21st Century", Hemispheres: Tufts Journal of International Affairs

- ↑ Morgan, Patrick M. (2003), Deterrence Now, Cambridge University Press

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Henry Kissinger (1973), Ending the Vietnam War: A history of America's Involvment in and Extrication from the Vietnam War, Simon & Schuster, p. 50 Cite error: Invalid

<ref>tag; name "Kissinger" defined multiple times with different content - ↑ Karnow, p. 582

- ↑ Carroll, James (June 14, 2005), "Nixon's madman strategy", Boston Globe

- ↑ Kissinger, p. 50

- ↑ Karnow, p. 591-592

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 75-78

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 27-28

- ↑ Kissinger, pp. 249-250

- ↑ Burr, William and Kimball, Jeffery, ed. (December 23, 2002), Nixon's Nuclear Ploy: The Vietnam Negotiations and the Joint Chiefs of Staff Readiness Test, October 1969, vol. George Washington University National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 81

- ↑ Military History Institute of Vietnam, Victory in Vietnam: The Official History of the People's Army of Vietnam, 1954-1975 (2002), Hanoi's official historyexcerpt and text search

- ↑ Shulimson, Jack, The Marine War: III MAF in Vietnam, 1965-1971, 1996 Vietnam Symposium: "After the Cold War: Reassessing Vietnam" 18-20 April 1996, Vietnam Center and Archive at Texas Tech University