Ulster Unionism: Difference between revisions

imported>Denis Cavanagh m (Wikilink) |

imported>Aleksander Stos m (typo) |

||

| Line 45: | Line 45: | ||

==Unionist control of Northern Ireland (1921-1972)== | ==Unionist control of Northern Ireland (1921-1972)== | ||

Subsequent Unionist parties controlled politics in Northern Ireland following the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. This act formally partitioned the island in the midst of the [[Anglo-Irish War]], causing | Subsequent Unionist parties controlled politics in Northern Ireland following the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. This act formally partitioned the island in the midst of the [[Anglo-Irish War]], causing separate parliaments to be established in both Belfast and Dublin. The Dublin parliament that was established was ignored by the southern rebels, who continued the conflict nonetheless until the [[Anglo-Irish Treaty]] in 1921. Northern Ireland, on the other hand was more than willing to exercise its newfound political rights and limited [[devolution]] style government. | ||

[[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|400px|Ulster in 1921]] | [[Image:Ulster1921.jpg|thumb|400px|Ulster in 1921]] | ||

Revision as of 06:27, 4 January 2008

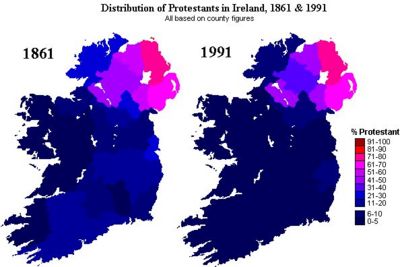

Ulster Unionism is the belief that Northern Ireland should remain in the United Kingdom and as an ideology first found prominence as far back as the Ulster Plantation in the early seventeenth century, when Scottish and some English colonists travelled to the counties of Ulster to establish communities, towns and farms. They mainly settled in counties Tyrone, Donegal, Armagh, Fermanagh, Londonderry and Cavan. Unlike previous waves of immigrants, the new colonists did not integrate into the indigenous culture and they left a legacy of loyalty to the Crown in an otherwise rebellious island. The southern Unionist movement, dominated by Sir Edward Carson (1854-1935), lost momentum with the formation of the Irish Free State in 1922.

History

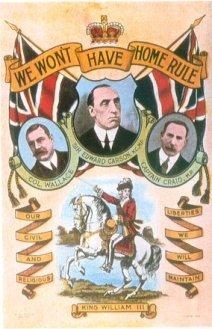

Ulster Unionism as a political force has its origins rooted in opposition to the Home Rule Movement, which Charles Stewart Parnell had organised in the late 19th century throughout the country, with his Home Rule Party. It had swept through Ireland and even took a seat in Liverpool in the 1885 elections. The concerted aim of the Home Rule Party was a form of national self determination. The Home Rule movement wished to have an independent parliament, capable of legislating for Irish interests, and they had won the balance of power several times when the Liberal Party controlled the British House of Commons. The Home Rule Party had an on and off alliance with the Liberals, but the Liberals did not control the House of Lords, which rejected Home Rule. When William Gladstone's first Home Rule Bill was passed by the Commons in 1886, Home Rule leaders like Parnell said Protestants would be welcome in a united Ireland. Unionists throughout Ireland detested the thought of Irish Home Rule, considering it to be "Rome Rule," that is, rule by the Roman Catholic

church. Another fear was of potential economic drag that would have hindered the industrialisation of Ulster.

Colonel Edward Saunderson was the chief Unionist leader in Ireland, and he did not at this time raise the partition issue. By 1893, when Gladstone's second Home Rule Bill passed in the Commons, the Unionists were starting to become well organised, with overtones of paramilitary formations, but still little talk of partition. With the Conservative party in power in London, 1895-1905, there was no threat of Home Rule.

The return of the Liberal Party in 1905 reopened the issue, and the Ulster Unionist Council was formed. After two close elections in 1910, the Liberals were forced to rely on the Irish Home Rule MP's and Asquith introduced the third Home Rule Bill in 1912. The proposal included an Irish parliament with no control over foreign or defense policy, or its own income. Unionists became alarmed when the Liberals broke the veto of the House of Lords, and the stage was set for passage in 1914. The new Unionist leader, Sir Edward Carson, collaborating with Conservative leader Andrew Bonar Law, now mounted a last-ditch effort. Talk of violence was widespread; the unionists were willing to fight to stay part of Britain. In the Ulster Covenant, 237,368 men, and 234,046 women pledged opposition to Home Rule and vowed to take all steps necessary to stop the "conspiracy" to force them out of the UK and put them at the mercy of their hereditary enemies.

In 1913-14 the Ulster Volunteer Force mobilized 100,000 men in paramilitary formations (that is they kept their civilian jobs and trained on weekends), supplied by 25,000 rifles smuggled in from Germany. The relied on an old statute which allowed subjects to drill and train with weapons so long as it was in the expressed defence of the monarchy. Eoin Mc Neill and other Nationalists then founded the Irish Volunteers in November 1913, with far fewer men and weapons.[1] John Redmond, the leader of the Home Rule party, had his people infiltrate and take over the Volunteers (which soon became the Irish Republican Army, or IRA). Redmond clung to the belief that parliamentary weapons would be used, and that his side had won. Armed rebellion by the Protestants was a stunning new development. Redmond rejected as "blasphemy" any proposals for partition, as suggested by some Liberals. When the British army gave signals that it would not operate against the Ulster rebels, a major crisis was at hand in London.

Asquith, however, seized on partition as the only solution. Meanwhile Carson demanded partition for all of Ulster. Suddenly World War I broke out, and it was agreed that Home Rule legislation would be approved but put in suspension until the war ended (people thought the war would be short - less than a year). Protestants, especially in Ulster, flocked to support the war effort, and gained much popular support in England for so doing; the Catholics were lukewarm on the war. Redmond accepted the compromise, and rapidly lost support to more radical elements who proposed to use the National Volunteers to fight the British until London gave them all of Ireland. Carson entered the cabinet in 1915, and now Ulster had a powerful position.

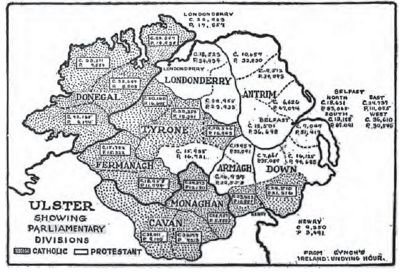

The harsh British reaction to the Easter Rising in 1916 radicalised the Catholics; they turned away from Home Rule and depended complete independence in their own republic. The Rising horrified the Unionists and Britain generally, as the issue was now polarised along religious-geographical lines. In the postwar election of 1918, the Home Rule party collapsed, replaced by the militant Sinn Féin of Éamon de Valera, which won 73 Irish seats (compared to 26 Unionist and 6 Home Rule party seats). The Unionists controlled the government in London and were prepared to give Home Rule to the south only, keeping Ulster in the UK. Carson's support of partition was accepted by the Ulster Unionist Council in June 1916, but rejected by leading southern unionists such as Lord Lansdowne and Lord Middleton. By 1920 Sir James Craig (1871-1940) replaced Carson as the main Unionist, and he wanted a six-county state, dropping three counties that had Catholic majorities. The result would be a two-thirds Protestant majority in Northern Ireland.

The IRA, under Michael Collins opened a guerrilla war in the south against the British, but had little impact in Ulster, where the Ulster Special Constabulary (comprising Protestant war veterans) had the upper hand. The British parliament passed the Government of Ireland Act, 1920 which officially partitioned the island into Southern Ireland and Northern Ireland. Northern Ireland in May 1921 elected its own parliament, at Stormont, with Craig as prime minister; Ireland was now partitioned with an operating government in Ulster firmly in place.

The Irish War of Independence continued on in the south, as the the rebels ignored the 1920 Act as being irrelevant to their demands for a republic that owed no allegiance to the crown. With Ulster now safe, British prime minister David Lloyd George called a truce in the south and opened negotiations with Sinn Féin for an independent southern Ireland. Agreement was reached, with the new Irish Free State to be nominally a member of the Commonwealth. The treaty was supported by Collins, who thought that Ulster would be economically too weak to survive on its own and would eventually join the south voluntarily; Collins also secretly planned guerrilla war in the north. The Irish Free State then came into being in the south. De Valera rejected the new state and the treaty's terms of independence, and rejected the majority votes in favor of the treaty in the cabinet, the Dáil, and in nationwide elections. Instead he started, and lost, the Irish Civil War of 1922-23. Catholic diehards, though out of power, dreamed of a united Ireland. Thus the Irish Troubles had their roots in the 1916-23 era, but are considered to have lasted from 1969-1998.

Ulster Unionist political theory

Ulster Unionism as an ideology or political theory possesses three pillars - political, economic and religious.

Political

One of the key arguments made by Ulster Unionists is that they are citizens of the United Kingdom and that they share a British or Ulster-Scots identity. Scotland is within visual distance along much of the Northern Ireland coastline and some of the islands are only a few kilometres away from the Irish mainland. They relate their identity with the United Kingdom and the British monarchy the same way that Irish nationalists and Republicans relate their identity with an independant, sovereign republic. They also feared that their rights as a people would be under-represented in a majority Catholic parliament. Unionist objections were further strengthened by support from the British Conservative Party. A prominent conservative, Lord Randolph Churchill, called on Unionists in Belfast to resist the implementation of Home Rule. He declared, "Ulster will fight and Ulster will be right!"[2] This was the beginning of an alliance between the Conservative and Unionist parties, which lasted into the next century.

Unionism in Northern Ireland was unified in 1905 with the formation of the Ulster Unionist Council, which linked the Orange Order and other Unionist groups together in one bloc. In 1910 Ulster Unionism came under the leadership of prominent Dublin University MP Edward Carson who told the Unionists of Northern Ireland to take over the institutions of government in Northern Ireland if Home Rule came to pass in 1911. The increasingly militant attitude of the Unionist leadership was confirmed by the formation of the Ulster Volunteer Force in 1913. In April 1914, 35,000 rifles and five million rounds of ammunition were smuggled into Larne Harbour and swiftly distributed throughout the province. With the outbreak of the First World War, the Ulster Volunteer Force comprised many of the troops of the 36th Ulster Division and lost many lives, particularly at the Battle of the Somme, which has entered into folklore.

Economic

The north-east was traditionally the most industrialised area of Ireland. Most of the island escaped the industrial revolution and employed an agrarian economy based largely on large landholders (usually British in ethnicity) and poor peasants who rented farmland from landlords, although land reform had transformed land ownership from large landlords into that of smaller, usually Catholic farmers. Belfast was a major centre of the textile and shipbuilding industries, with Harland and Wolff employing many thousands in the shipyards. This argument was further reinforced with the advent of the Welfare State in Britain following World War II, with Northern Irish Catholics and Protestants receiving much superior benefits than their southern conterparts.

The economy of the Republic of Ireland has exploded in the last two decades, however, with the Celtic Tiger economy, and now is more developed than that of Northern Ireland, and the Unionist economic argument has stagnated.

Religious

Many Unionists feared a Roman Catholic majority legislating against Protestant interests in a Dublin based parliament. They summed this up with the old adage: "Home Rule is Rome Rule".[3] Unionists also feared the widespread dominance of the Roman Catholic Church in Irish society and the political power it possessed. As the South gained its independence this did indeed come to pass to a large extent. Legislation approved by or prompted by the Catholic Church was quickly introduced, and included a ban on contraception and the outlawing of divorce. The Roman Catholic Church was recognised as having a "special position" in the 1937 Constitution of Ireland. An innovative social welfare scheme, the "Mother and Child Scheme", was discontinued in the 1950s largely at the behest of the Catholic Church.

However, the Republic of Ireland has gradually become much more secular in recent years, with contraception and divorce now legalised and the practice of homosexuality being decriminalised. Religion has begun to play a much lesser role in people's lives, as the number of nominal Catholics proves.

Unionist control of Northern Ireland (1921-1972)

Subsequent Unionist parties controlled politics in Northern Ireland following the 1920 Government of Ireland Act. This act formally partitioned the island in the midst of the Anglo-Irish War, causing separate parliaments to be established in both Belfast and Dublin. The Dublin parliament that was established was ignored by the southern rebels, who continued the conflict nonetheless until the Anglo-Irish Treaty in 1921. Northern Ireland, on the other hand was more than willing to exercise its newfound political rights and limited devolution style government.

Modern Ulster Unionism

Modern day Ulster Unionism has reached a consensus, favouring dialogue and peace with Republicans. Many of Northern Ireland's most famous Unionists, such as Ian Paisley have advocated and taken part in negotiations with Sinn Féin. Following the most recent Northern Ireland Assembly elections, the Democratic Unionist Party and Sinn Féin agreed to go into government together, with Paisley as First Minister and Martin Mc Guinness - a former Provisional IRA bomber - as the Deputy First Minister. The Cabinet is a mixed Republican/Unionist one.

In the runup to the 2007 Assembly elections, both parties campaigned on issues such as water charges and business development, issues that could appeal to both sides of the community. Sectarianism and partisan politics, usually a frequent occurance in a Northern Irish election were minimised and in some cases avoided. Since the Provisional IRA had decommissioned its weapons years earlier and Sinn Féin had recognised the PSNI, the Democratic Unionist Party reluctantly agreed to consider going into government with Sinn Féin, who won a considerably large minority in the election.

The early months of the government has seen frequent shows of unity between First Minister Paisley and Deputy First Minister Mc Guiness. Both men have appeared at many sites and places and are trying to rebuild Northern Ireland following generations of sectarian warfare.

List of Unionist political and social organisations

- Democratic Unionist Party

- Ulster Unionist Party

- Progressive Unionist Party

- United Kingdom Unionist Party

- Orange Order

References

- ↑ The Irish Volunteers, by contrast, were not allowed to drill legally and any weapons they imported, such as in the Howth gun running incident, were strictly illegal.

- ↑ Winston Churchill, Lord Randolph Churchill Page 65.

- ↑ Arthur, Paul; Government and Politics of Northern Ireland - Page 7

Bibliography

- Adamson, Ian. The Identity of Ulster, 2nd edition (Belfast, 1987)

- Arthur, Paul. Government and Politics of Northern Ireland

- Bardon, Jonathan. A History of Ulster (Belfast, 1992)

- Bew, Paul, Peter Gibbon and Henry Patterson, Northern Ireland 1921-1994: Political Forces and Social Classes (1995)

- Bew, Paul. Ideology and the Irish Question: Ulster Unionism and Irish Nationalism 1912-1916

- Brady, Claran, Mary O'Dowd and Brian Walker, eds. Ulster: An Illustrated History (1989)

- Boyce, D. George. "Carson, Edward Henry, Baron Carson (1854–1935)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography 2004. online

- Boyce, D. George. "Craig, James, first Viscount Craigavon (1871–1940)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography,2004; online edn,

- Elliott, Marianne. The Catholics of Ulster: A History. Basic Books. 2001. online edition

- Farrell, Michael. Northern Ireland: The Orange State, 2nd edition (London, 1980)

- Henessy, Thomas. A History of Northern Ireland, 1920-1996. St. Martin's, 1998. 365 pp.

- Mitchel, Patrick; Evangelicalism and National Identity in Ulster, 1921-1998

- Hostettler, John; Sir Edward Carson: A Dream Too Far