Iraq War: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 113: | Line 113: | ||

The alternative, preferred by Franks, was called RUNNING START, and was chosen. It moved Special Operations preparation into Phase I, made the air and ground phases essentially simultaneous (i.e., merged into a combined Phase III of [[#decisive combat operations|decisive combat operations]]), and then a reconstruction phase; the phases were not renumbered. | The alternative, preferred by Franks, was called RUNNING START, and was chosen. It moved Special Operations preparation into Phase I, made the air and ground phases essentially simultaneous (i.e., merged into a combined Phase III of [[#decisive combat operations|decisive combat operations]]), and then a reconstruction phase; the phases were not renumbered. | ||

During the planning phase, Rumsfeld told Franks that LTG Jay Garner would be responsible for reconstruction, reporting to CENTCOM. <ref>Franks, pp. 422-423</ref> A number of retired generals have been highly critical of the plan, focused especially on what they considered the unrealistic goals of Secretary of Defense [[Donald Rumsfeld]]. They include [[Paul Eaton]], who headed training of the Iraqi military in 2003-2004; formal chiefs of [[United States Central Command]] ([[Anthony Zinni]] and [[Joseph Hoar]]); [[ | During the planning phase, Rumsfeld told Franks that LTG Jay Garner would be responsible for reconstruction, reporting to CENTCOM. <ref>Franks, pp. 422-423</ref> A number of retired generals have been highly critical of the plan, focused especially on what they considered the unrealistic goals of Secretary of Defense [[Donald Rumsfeld]]. They include [[Paul Eaton]], who headed training of the Iraqi military in 2003-2004; formal chiefs of [[United States Central Command]] ([[Anthony Zinni]] and [[Joseph Hoar]]); [[Greg Newbold]], Director of the [[Joint staff]] from 2000 to 2002; [[John Riggs]], a planner who had criticized personnel levels, in public, while on duty; [[division|division commander]]s [[Charles Swannack]] and [[John Baptiste]].<ref name=Deary>{{citation | ||

|title= Six agaist the Secretary: the Retired Generals and Donald Rumsfeld | |title= Six agaist the Secretary: the Retired Generals and Donald Rumsfeld | ||

|first = David S. | last = Deary | |first = David S. | last = Deary | ||

Revision as of 11:04, 25 May 2009

Template:TOC-right The Iraq War was the invasion of Iraq in 2003 by a multinational coalition led by the United States of America. Military operations were conducted by forces from the U.S., the United Kingdom, Australia and Poland, and was supported in various ways by many other countries, some of which allowed attacks to be launched or controlled from their territory. The U.N. neither approved nor censured the war, which was never a formally declared war. The U.S. refers to it as Operation IRAQI FREEDOM. Continuing operations are under the command of Multi-National Force-Iraq.

This war is to be distinguished from the Gulf War of 1991, following the Iraqi invasion of Kuwait in 1990. The Gulf War had United Nations authorization. Further, both these wars should be differentiated from the Iran-Iraq War of 1980-1988.

The war had quick result of the removal (and later execution) of Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein and the formation of a democratically elected parliament and ratified constitution, which won UN approval. However, an amorphous insurgency since then has produced large numbers of civilian deaths and an unstable Iraqi government. It has generated enormous political controversy in the U.S. and other countries.

The main rationale for the invasion was Iraq’s continued violation of the 1991 agreement (in particular United Nations Resolution 687) that the country allow UN weapons inspectors unhindered access to nuclear facilities, as well as the country’s failure to observe several UN resolutions ordering Iraq to comply with Resolution 687. The US government cited intelligence reports that Iraq was actively supporting terrorists and developing weapons of mass destruction (WMD) as additional and acute reasons to invade. Though there was some justification before October 2002 for believing this intelligence credible, a later Senate investigation found that the intelligence was inaccurate and that the intelligence community failed to communicate this properly to the Bush administration[1].

Factors Leading Up to the Invasion

There were a wide range of opinions that Saddam Hussein's Iraq had a negative effect on regional and world stability, although many of the opinionmakers intensely disagreed on the ways in which it was destabilizing. This idea certainly did not begin with 9/11.

Clinton Policy and Weapons Inspections

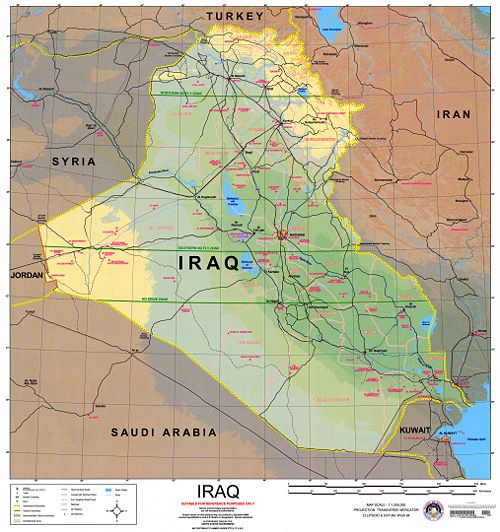

After the Gulf War in 1991, United Nations Resolution 687 specified that Iraq must destroy all weapons of mass destruction (WMD). A large amount of WMDs were indeed destroyed under UN supervision (UNSCOM). Two no-fly zones were also instituted in northern and southern Iraq where Iraqi military aircraft were prohibited from flying. The United States and the United Kingdom (and France until 1998) patrolled these zones in, respectively, Operation NORTHERN WATCH and Operation SOUTHERN WATCH. The 1996 Khobar Towers bombing attacked forces, in Saudi Arabia, conducting SOUTHERN WATCH.

However, by late 1997, the the Clinton administration became dissatisfied with Iraq’s increased unwillingness to cooperate with UNSCOM inspectors. As a result of widespread expectations that the Clinton administration would decide to act with military force, the UN weapons inspectors were evacuated from the country. Iraq and the United Nations agreed to resume weapons inspections, but Saddam Hussein continued to obstruct UNSCOM teams throughout the remainder of 1998.

Congress passed the Iraq Liberation Act in October 1998:

It should be the policy of the United States to support efforts to remove the regime headed by Saddam Hussein from power in Iraq and to promote the emergence of a democratic government to replace that regime. [2]

In December 1998, President Clinton authorized military action against Iraq. Between December 16 and 19, 1998, US and UK missiles and aircraft attcked military and government targets in Iraq in Operation DESERT FOX. It was widely understood that the Clinton administration intended Operation Desert Fox to be not merely a campaign of punishment for Iraq’s failure to cooperate but also to weaken the regime in advance of orchestrated efforts to cause regime change. In that respect, Clinton administration policy was ineffective.

As a result of Iraq’s barring inspectors from the country, UNSCOM inspections of Iraq’s WMD effectively came to an end and in March 1999, the UN concluded that the UNSCOM mandate should end. In December 1999, the UN passed UN Security Council Resolution 1284, setting up UNMOVIC (United Nations Monitoring, Verification and Inspection Commission), headed by Swedish diplomat Hans Blix, which was to identify the remaining WMD arsenals in Iraq. Because UNMOVIC was banned from Iraq, the world had to rely on indirect evidence, most of which turned out to be false or inaccurate.[3] Iraq policy during the remainder of the Clinton presidency was marked by a return to the containment regime that existed before Operation Desert Fox, but now without the benefit of direct intelligence.

Bush Administration Policy

Policy before 9/11 Attacks

In the early days of the Bush administration, President George W. Bush expressed dissatisfaction with his predecessor’s foreign policy, in particular with regard to Iraq, which he considered weak and half-hearted. Interestingly, the main thrust of Bush criticism was that President Clinton had been too widely engaged in too many conflicts, acting as the “world’s policeman.” In the end, President Bush believed Clinton had lacked the necessary resolve to hold Saddam Hussein accountable for his failure to comply with UN resolutions. Bush also questioned America’s membership in NATO and involvement in UN diplomacy, which led some to believe he was moving towards a more isolationist view of foreign policy.[4]

At the same time, Bush continued to favor executing the policy President Clinton had approved but not acted on: to actively proceed to effect regime change in Iraq. In January 2002, Time Magazine reported that since President Bush took office he had been grumbling about finishing the job his father started. [5]

On February 16, 2001 a number of US and UK warplanes attacked Baghdad, nearly two years before the start of the Iraq war. [6].

Iraqi WMD and the War on Terror

The attacks of September 11, 2001 shaped the policies of the Bush administration towards Iraq. President Bush saw them as confirmation of his beliefs that the international community’s failure to enforce compliance with UN resolution and America’s irresolute foreign policy had emboldened rogue states and international terrorist groups. Because Iraq was known to have had and used WMD in the past and because Iraq had blocked UN supervision of the destruction of its WMD, there remained great uncertainty about Iraq’s WMD arsenal. The Bush administration made Iraq of central importance to its national security policy. Combined with his isolationist foreign policy beliefs, President Bush started to formulate what has become known as the Bush Doctrine. The doctrine is most fully expressed in the administration’s National Security Strategy of the United States of America, published in September 2002. In it, the President states:

We will disrupt and destroy terrorist organizations by (…) direct and continuous action using all the elements of national and international power. Our immediate focus will be those terrorist organizations of global reach and any terrorist or state sponsor of terrorism which attempts to gain or use weapons of mass destruction (WMD) or their precursors.[7]

The administration included Iraq in a series of states it considered acutely dangerous to world peace. In his 2002 State of the Union President Bush called Iraq part of an “axis of evil” together with Iran and North Korea.[8] In this address the president also claimed the right to wage a preventive war, as distinct from a preemptive attack. Early in 2002, the administration began pressuring Iraq as well as the international community on greater compliance by Iraq with UN resolutions.

The Niger Uranium Forgeries

In February 2002, as a result of the discovery of classified documents initially revealed by Italian intelligence in October 2001, the Pentagon sent Marine General Carlton W. Fulford, Jr. to Niger to investigate the claim that Iraq was attempting to buy uranium to revamp its nuclear WMD program. That same month, the CIA sent former Ambassador Joseph Wilson IV to Niger in February 2002. General Fulford and Ambassador Wilson interviewed several high-ranking Niger government officials. Neither found any evidence for the sale; Mr. Wilson concluded that the claim was “unequivocally wrong.”[9]

There was disagreement about the findings of Mr. Wilson’s report within the intelligence community. CIA analysts believed the report confirmed reports about an Iraq-Niger uranium deal, partly because Mr. Wilson’s report included a comment that an Iraqi envoy had visited the African country in 1999. However, State Department analysts decided that Niger would be unwilling or incapable of supplying Iraq with any uranium.[10] As a result of these conflicting intelligence analyses, the Bush administration remained suspicious and continued to work from the assumption that Saddam Hussein was actively trying to acquire a nuclear weapon. Because of internal disorganization, the CIA failed to obtain copies of the original classified documents, after they were finally made available to American intelligence in October 2002, and ignored warnings from State Department analysts about problems with the documents. The CIA also failed to check the the president’s 2003 State of the Union for factual errors. Consequently, the address included the infamous “sixteen words” that “the British government has learned that Saddam Hussein recently sought significant quantities of uranium from Africa.” [11][12] It was not until March 2003 that the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) revealed with conclusive proof that the documents at the basis of the allegations were forgeries.[13] However, the British government claimed it had evidence to the same effect independent of these documents, but had promised the source not to reveal its identity.

Resumption of Weapons Inspections in 2002

The continued belief that Iraq was pursuing nuclear weapons led the Bush administration to increase diplomatic pressure on the Iraqi regime. During a speech before the General Assembly of the United Nations on September 12, 2002, President Bush outlined a long list of complaints against the Iraqi government. This included active support and harboring of terrorists (among them members of al Qaeda who had fled from Afghanistan after the US invaded that country), continued development of prohibited missiles, diverting funds from the UN “Oil for Food” program to purchase weapons, and violation of several UN resolutions by refusing to be open about its WMD arsenal.[14] On November 8, 2002, the United Nations Security Council unanimously passed resolution 1441 which declared Iraq in material breach of the 1991 ceasefire agreement and demanded Iraq fully comply with its disarmament obligations.[15] As a result, Iraq agreed to let UNMOVIC weapons inspectors, headed by Hans Blix, back into the country.

Strategic planning

Even before the 9-11 attacks, regime change in Saddam Hussein's Iraq was a high priority of the George W. Bush Administration. This is not to suggest that previous Administrations had not been considering it, and had been steadily carrying out air attacks in support of the no-fly zones (Operation SOUTHERN WATCH and Operation NORTHERN WATCH), as well as air strikes (Operation DESERT FOX). Nevertheless, the priorities changed.

Another change, in the Bush Administration, was an emphasis on [[military transformation]], or not fighting the last war. Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld was a constant advocate of transformation, emphasizing higher technology, more flexibility, and smaller forces. This was especially true after early operations in the Afghanistan War (2001-), where large U.S. ground forces were not used, but instead extensive special operations working with Afghan forces and using air power. Every war is different, however, and the reality in Afghanistan is there was an existing civil war and substantial indigenous resistance forces.

Late in the evening of 9/11, the President had been told, by CIA chief George Tenet, that there was strong linkage to al-Qaeda. [16] On September 12, President Bush directed counterterrorism adviser Richard Clarke to review all information and reconsider if Saddam was involved in 9/11.[17]

Deputy Secretary of Defense Paul Wolfowitz sent Rumsfeld a memo, on September 17, called "Preventing More Events"; it argued that there was a better than 1 in 10 chance that Saddam was behind 9/11. [18] He had been told, by the CIA and FBI, that there was clear linkage to al-Qaeda, but said the CIA lacked imagination.[19]

On September 19, 2001, the advisory Defense Advisory Board, chaired by Richard Perle, met for two days. Iraq was the focus. Among the speakers was Ahmed Chalabi, a controversial Iraqi exile who argued for an approach similar to the not-yet-executed approach to Afghanistan: U.S. air and other support to insurgent Iraqis. [20]

Reviews by Rumsfeld

CENTCOM had a contingency plan for a new war with Iraq, designated OPLAN 1003-98. It assumed Iraq would launch an attack as it had done in 1990. According to GEN Anthony Zinni, who had been CENTCOM commander when Franks commanded its Army component, Franks was "the major contributor to [its] force levels and its planning and everything else. He was more involved in it than just about anyonene else." [21] Zinni had recommended that Franks succeed him at CENTCOM.

Rumsfeld had OPLAN 1003-98 presented by LTG Greg Newbold, director of operations for the Joint Chiefs of Staff, in late 2001. Rumsfeld believed the plan, which called for up to 500,000 troops, was far too large; Rumsfeld thought that no more than 125,000 would be needed. Newbold later said he regretted he did not say, at the time,

Mr. Secretary, if you try to put a number on a mission like this, you may cause enormous mistakes. Give the military the task, give the military what you would like to see them do, and let them come up with it. I was the junior military man in the room, but I regret not saying it[22]

Informally, it had been called "DESERT STORM II", using three corps as in 1991, but to force collapse of Saddam Hussein's regime. Franks told Rumsfeld, on December 4, 2001, that it was a stale, troop-heavy concept. He told the Secretary of Defense that he had a new concept, but that detailed planning would be needed. [23]

Rumsfeld calls for new planning

On October 9, 2002, GEN Eric Shinseki, Chief of Staff of the Army, told staff officers "From today forward the main effort of the US Army must be to prepare for war with Iraq". [24]

Theater/operational planning

In the Gulf War, there was no common commander for all land forces; GEN H Norman Schwarzkopf Jr. gave direct orders to the U.S. Army and Marine unites. Experience both then and in WWII showed the need for a land forces commander.

In November 2001, the commander of United States Central Command, Tommy Franks[25] designated Third United States Army as the CENTCOM Land Forces Component Command (CFLCC). LTG David McKiernan took command of Third Army in September 2002. According to MG Henry "Hank" Stratman, deputy commanding general for support of Third Army, eventual combat with Iraq was assumed when he took his post in the summer of 2001, even before the 9-11 attack.

V Corps, then in Germany, was made the lead ground tactical planning headquarters, under CFLCC, in April 2002. It deployed to Poland and conducted Exercise VICTORY STRIKE, a training exercise with Iraq in mind. Under CFLCC, a command exercise, LUCKY WARRIOR, in Kuwait, involved V Corps and I MEF. Next, the annual CENTCOM exercise, INTERNAL LOOK, added practice for the Joint Force Air Component Command (JFACC), while Special Operations Command for CENTCOM (SOCCENT) formally established two Joint Special Operations Task Forces (JSOTF): JSOTF-North and JSOTF-West. It assumed I MEF with part of its air wing, 1st Marine Division with two regimental combat teams, and V Corps with all of 3rd ID, an attack helicopter regiment, and part of the corps artillery. [24]

Detailed planning by CENTCOM began while active combat was ongoing in Afghanistan, in December 2002. [26] At the time, GEN Eric Shinseki, then Chief of Staff of the Army, testified to Congress that the number of troops approved by Rumsfeld was inadequate. Shinseki, however, was not in the chain of command for operational deployment, although he was the senior officer of the United States Army.

GEN Franks briefed Secretary Rumsfeld on February 1, with two alternative plans. The first, informally called "DESERT STORM II", repeated the sequential approach of Operation DESERT STORM:[27]

- Phase I: buildup of forces before invasion, with increased air strikes in the no-fly zones and early staging of special operations forces; prestaging of approximately 160,000 troops

- Phase II: Air-centric operations of approximately 3 weeks, preparing the battlefield for the major ground forces attacks

- Phase III: Major ground forces attack with approximately 105,000 troops

- Phase IV: Occupation and reconstruction

The alternative, preferred by Franks, was called RUNNING START, and was chosen. It moved Special Operations preparation into Phase I, made the air and ground phases essentially simultaneous (i.e., merged into a combined Phase III of decisive combat operations), and then a reconstruction phase; the phases were not renumbered.

During the planning phase, Rumsfeld told Franks that LTG Jay Garner would be responsible for reconstruction, reporting to CENTCOM. [28] A number of retired generals have been highly critical of the plan, focused especially on what they considered the unrealistic goals of Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. They include Paul Eaton, who headed training of the Iraqi military in 2003-2004; formal chiefs of United States Central Command (Anthony Zinni and Joseph Hoar); Greg Newbold, Director of the Joint staff from 2000 to 2002; John Riggs, a planner who had criticized personnel levels, in public, while on duty; division commanders Charles Swannack and John Baptiste.[29]

Major combat phase

Air attacks began at 5:34 AM (local time) on March 19, 2003, with carrier aircraft and cruise missiles from ships in international waters. There were additional F-117 Nighthawk stealth aircraft flying from undisclosed bases; while it can be mid-air refueled, it would likely have launched from a base relatively near Iraq. Special operations forces were already operating in Iraq.

Some of the air strikes targeted Saddam Hussein personally. [30]

The first ground combat took at 3:57 PM, but south of the Iraqi border, between Iraqi vehicles and U.S. Marine Corps reconnaissance vehicles. Marines began the actual attacks with artillery fire in the late afternoon, preceding the border crossing by the 1st Marine Division under I Marine Expeditionary Force under then-LTG James Conway. The Division cooperated closely with 1 Armored Division (U.K.) and the Army's 3d Infantry Division (U.S.)[31] The Army units were under V Corps, commanded by LTG William "Scott" Wallace.

Lead Marine units crossed the Kuwait-Iraq border and began an intensive attack on Safwan Hill, in Iraq just north of the border. [32]

Interim Military Government

On April 16, declared the end of combat. [33] Franks ordered the withdrawal of the major U.S. combat units. The CENTCOM forward headquarters in Qatar and I MEF were to be withdrawn. U.S. forces would be reduced to 30,000 by the end of August, which the U.S. believed was adequate. [34]

CFLCC was redesignated Combined Joint Task Force 7 (CJTF-7) on May 1, but McKiernan's headquarters was replaced by V Corps, then under LTG Wallace. MG Ricardo Sanchez, then commanding 1st Armored Division (U.S.) in Germany, was promoted to LTG and given command of V Corps. According to Sanchez, Franks had not specified a specific Phase IV role for CENTCOM or V Corps. [35]

Insurgency, Counterinsurgency, or Occupation, depending on perspective

The headquarters for foreign military units in Iraq is Multi-national Force-Iraq (MNF-I). On an overall basis, it reports to the United States Central Command, which also commands the U.S. troops in MNF-I. Other units report to their home nations, although there are a number of non-US commanders from the MNF-I Deputy Commanding General, and Australian, British and Polish commanders at division level.

References

- ↑ United States Senate (July 7, 2004), Report on the U.S. Intelligence Community's Prewar Intelligence Assessments on Iraq

- ↑ Iraq Liberation Act of 1998

- ↑ Ali A. Allawi. The Occupation of Iraq: Winning the War, Losing the Peace. New Haven (Conn.): Yale University Press, 2007, p. 72.

- ↑ Cameron G. Thies. “From Containment to the Bush Doctrine: The Road to War with Iraq.” In: John Davis ed. Presidential Policies and the Road to the Second Iraq War. Aldershot (UK)/Burlington (VT):Ashgate, 193-207, here p. 200.

- ↑ http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,235395,00.html Time Magazine reports

- ↑ http://archives.cnn.com/2001/WORLD/meast/02/16/iraq.airstrike/ CNN reports

- ↑ National Security Strategy of the United States of America, The White House, September 2002. (Page 6 in the printed edition). Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ 2002 State of the Union address, President George W. Bush, January 29, 2002. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ REPORT ON THE U.S. INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY'S PREWAR INTELLIGENCE ASSESSMENTS ON IRAQ United States Senate, ordered July 7, 2004. Chapter 2-b. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ REPORT ON THE U.S. INTELLIGENCE COMMUNITY'S PREWAR INTELLIGENCE ASSESSMENTS ON IRAQ United States Senate, ordered July 7, 2004. Chapter 2-k. Conclusion 13. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ↑ 2003 State of the Union Address, President George W. Bush, January 28, 2003. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ Senate Intelligence Committee Report (see previous note), Chapter 2-k. Conclusions 18-19, 21.

- ↑ Transcript of ElBaradei's U.N. presentation, posted at CNN. March 7, 2003. Retrieved May 8, 2008.

- ↑ President George W. Bush’s 2002 Address to the UN General Assembly, United Nations, General Assembly 57, Meeting 2. Verbatim Report. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ↑ United Nations Security Council Resolution 1441, posted at CNN.com, November 8, 2002. Retrieved May 9, 2008.

- ↑ George Tenet with Bill Harlow (2007), At the Center of the Storm: My Years at the CIA, Harpercollins, p. 169

- ↑ Richard A. Clarke (2004), Against all Enemies: Inside America's War on Terror, Free Press, Simon & Schuster, ISBN 0743260244, p. 31

- ↑ Michael Isikoff, David Corn (2006), HUBRIS: the Inside Story of Spin, Scandal and the Selling of the Iraq War, Crown/Random house, ISBN 0307346811, p. 80}}

- ↑ Isikoff & Corn, p. 108

- ↑ Michael R. Gordon, Bernard E. Trainor (2006), COBRA II: the inside story of the invasion and occupation of Iraq, Pantheon, ISBN 0375422625,COBRA II, p. 27

- ↑ COBRA II, p. 27}}

- ↑ COBRA II, p. 4

- ↑ Franks, p. 331

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Gregory Fontenot, E. J. Degen, David Tohn. United States Army Operation Iraqi Freedom Study Group (2005), Chapter 2: Prepare, Mobilize, and Deploy, On Point: The United States Army in Operation Iraqi Freedom, Center for Army Lessons Learned, p. 29, Note 1

- ↑ unrelated to Gen. Fred Franks in the Gulf War

- ↑ Franks, Tommy & Malcolm McConnell (2004), American Soldier, pp. 329-335

- ↑ Franks, p. 366-370

- ↑ Franks, pp. 422-423

- ↑ Deary, David S. (February 23, 2007), Six agaist the Secretary: the Retired Generals and Donald Rumsfeld, Air War College

- ↑ Gellman, Barton & Dana Priest (March 20, 2003), CIA Had Fix on Hussein: Intelligence Revealed 'Target of Opportunity'

- ↑ 1st MarDiv Staff Secretary (March 2006), History of 1st Marine Division, "The Old Breed"

- ↑ United States Marine Corps, 3rd Light Armored Reconnaissance Battalion

- ↑ Franks, pp. 528-529

- ↑ Ricardo S. Sanchez with Donald T. Phillips (2008), Wiser in Battle: a Soldier's Story, HarperCollins, ISBN 9780061562426, pp. 168

- ↑ Sanchez, p. 171