Global warming: Difference between revisions

imported>Greg Harris No edit summary |

imported>Greg Harris |

||

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

==Related climatic issues== | ==Related climatic issues== | ||

A variety of issues are often raised in relation to global warming. One is [[ocean acidification]]. Increased atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> increases the amount of CO<sub>2</sub> dissolved in the oceans.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://science.hq.nasa.gov/oceans/system/carbon.html |title=The Ocean and the Carbon Cycle |accessdate=2007-03-04 |date=[[2005-06-21]] |work=[[NASA]]}}</ref> CO<sub>2</sub> dissolved in the ocean reacts with water to form [[carbonic acid]] resulting in acidification. Ocean surface [[pH]] is estimated to have decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14 since the beginning of the industrial era | A variety of issues are often raised in relation to global warming. One is [[ocean acidification]]. Increased atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub> increases the amount of CO<sub>2</sub> dissolved in the oceans.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://science.hq.nasa.gov/oceans/system/carbon.html |title=The Ocean and the Carbon Cycle |accessdate=2007-03-04 |date=[[2005-06-21]] |work=[[NASA]]}}</ref> CO<sub>2</sub> dissolved in the ocean reacts with water to form [[carbonic acid]] resulting in acidification. Ocean surface [[pH]] is estimated to have decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14 since the beginning of the industrial era.<ref>{{cite journal |last= Jacobson |first= Mark Z. |date= [[2005-04-02]] |title= Studying ocean acidification with conservative, stable numerical schemes for nonequilibrium air-ocean exchange and ocean equilibrium chemistry |journal= [[Journal of Geophysical Research]] |volume= 110 |issue= D7 |id= D07302 |url= http://www.stanford.edu/group/efmh/jacobson/2004JD005220.pdf |format=[[Portable Document Format|PDF]] |doi = 10.1029/2004JD005220 |accessdate=2007-04-28}}</ref> The key word here is "surface", keeping in mind that the surface of the ocean accounts for a miniscule portion of the total ocean volume. Plus as the surface of the ocean warms known physical processes drive dissolved carbon dioxide out of solution, suggesting theories of ever decreasing pH due to increasing dissolved carbon dioxide gas are flawed. Nevertheless, it is estimated that it will drop by a further 0.14 to 0.5 units by 2100 as the ocean absorbs more CO<sub>2</sub>.<ref name=grida7/><ref>{{cite journal| last = Caldeira | first = Ken | coauthors= Wickett, Michael E. | title = Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean | journal = [[Journal of Geophysical Research]] |volume = 110 |issue = C09S04 | doi:10.1029/2004JC002671 | pages = 1–12 | url = http://www.agu.org/pubs/crossref/2005/2004JC002671.shtml | date = [[2005-09-21]] | accessdate = 2006-02-14}}</ref> Note that this is between two and five times the suggested present observed change and it is projected to occur over signficantly less time. As with past IPCC and general alarmist predictions which never managed to come true this one will have to be seen to be believed. Since organisms and ecosystems are adapted to a narrow range of pH, this raises [[extinction]] concerns, directly driven by increased atmospheric CO<sub>2</sub>, that could disrupt food webs and impact human societies that depend on marine ecosystem services except for the fact that the observed and any reasonably projected future changes are still within those narrow ranges, of course. <ref>{{cite paper |author=Raven, John A.; ''et al.'' |title= Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide |publisher= [[Royal Society]] |date= [[2005-06-30]] |url= http://www.royalsoc.ac.uk/displaypagedoc.asp?id=13314 |format= [[Active Server Pages|ASP]] |accessdate= 2007-05-04}}</ref> | ||

Another related issue that may have partially mitigated global warming in the late twentieth century is [[global dimming]], the gradual reduction in the amount of global direct [[irradiance]] at the Earth's surface. From 1960 to 1990, human-caused aerosols likely precipitated this effect. Scientists have stated with 66–90% confidence that the effects of human-caused aerosols, along with volcanic activity, have offset some of global warming, and that greenhouse gases would have resulted in more warming than observed if not for these dimming agents.<ref name=grida7/> | Another related issue that may have partially mitigated global warming in the late twentieth century is [[global dimming]], the gradual reduction in the amount of global direct [[irradiance]] at the Earth's surface. From 1960 to 1990, human-caused aerosols likely precipitated this effect. Scientists have stated with 66–90% confidence that the effects of human-caused aerosols, along with volcanic activity, have offset some of global warming, and that greenhouse gases would have resulted in more warming than observed if not for these dimming agents.<ref name=grida7/> | ||

Revision as of 04:45, 31 January 2008

Global warming is the increase in the average temperature of the Earth's near-surface air and oceans in recent decades and its projected continuation.

Global average air temperature near the Earth's surface rose 0.74 ± 0.18 °C (1.33 ± 0.32 °F) from 1906 to 2005. One view, as represented by the science academies of the major industrialized nations[1] and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC),[2] is that most of the temperature increase since the mid-20th century has been very likely caused by increases in atmospheric greenhouse gas concentrations produced by human activity. Another view suggests that global warming and global cooling are recurring natural events with little or no anthropogenic influences.

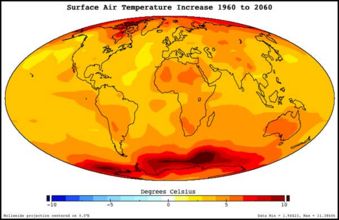

Climate models project that global surface temperatures are likely to increase by 1.1 to 6.4 °C (2.0 to 11.5 °F) between 1990 and 2100.[2] The range of values reflects the use of differing assumptions of future greenhouse gas emissions and results of models that differ in their sensitivity to increases in greenhouse gases.[2] The latest IPCC report, Working Group I Chapter 8 (see pages 600-647) [3], contains pages of admissions regarding the shortcomings of climate models, which still cannot accurately predict both temperature and precipitation at the same time. IPCC concerns reflect reality as the climate models the IPCC used as a primary basis for their predictions and conclusions routinely fail to accurately predict climate. [4][5] The reasons are not hard to discover. Climate models have known significant shortcomings. [6] [7] The consensus view is that they are incapable of performing their primary task. [8] The IPCC practice is to accept that each of the climate models has serious shortcomings. Their methodology is to take all the known wrong answers and sum them together then bless the result as correct.

An increase in global temperatures will in turn cause sea level rise, glacier retreat, melting of sea ice, and changes in the amount and pattern of precipitation. Though world climate catastrophe meetings and news media reports featured dire warnings about changes in the frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, anecdotal evidence suggests otherwise, particularly with respect to repeated warnings regarding global warming's effects on tropical cyclones. After an unusually robust North Atlantic hurricane season in 2005 dire predictions that anthropogenic warming would cause worse seasons in 2006 and 2007 failed to translate into fact. Both seasons were decidedly tame. [9] In truth no valid link exists that connects specific weather events, or any trend in them, to global warming whatever the true cause, anthropogenic or natural. Patterns of drought and deluge, heat and cold have exhibited unpredictable variability long before alleged anthropogenic climate change alarmism became sexy and trendy. Changes to the climate will produce a range of practical effects, such as changes in agricultural yields and impacts on human health as they have in the past according to historical records, which show that colder times feature severe illness and major crop failures while warmer times feature robust health and substantially increased crop yields.

Remaining scientific uncertainties include the exact degree of climate change expected in the future, and how changes will vary from region to region around the globe.[10] There is ongoing political and public debate regarding what, if any, action should be taken to reduce future warming or to adapt to its consequences as it is pointed out by some that the trillions of dollars proposed to be spent in vain attempts to stop what may in fact turn out to be irresistible natural forces could better be spend on real world problems with proven causes and solutions. The Kyoto Protocol, an international agreement aimed at reducing greenhouse gas emissions, was adopted by 169 nations, yet it exempted the two most populous and most polluting nations on Earth, India and China. During more recent climate talks in Bali in 2007, China made it clear that the world should not expect any emissions reductions even though China was recently acknowledged to be the number one carbon dioxide emitter in the world. Furthermore China bluntly informed the delegates gathered in Bali that emissions will drastically increase as China embarks on a program to build over 550 coal-fired powerplants over the next 20 years. Even as the meetings that produced Kyoto were winding down, delegates to Kyoto, including Al Gore, were admitting that the treaty would do little if anything to solve what they saw as the main problem - anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions. They were right. In the years since it was written even those who formally ratified it found ways to adjust their efforts to comply to make them even more meaningless. [11] Naturally, failure of Kyoto led to the usual political response - proposal of taxes. [12] The one true consensus regarding global warming seems to be that Kyoto was indeed a complete failure. [13]

Terminology

The United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) uses the term "climate change" for human-caused change, and "climate variability" for other changes.[3] The terms "anthropogenic global warming" and "anthropogenic climate change" are sometimes used when focusing on human-induced changes.

Causes

The climate system varies both through internal processes and in response to external forcing. External forcing includes solar activity, volcanic emissions, variations in Earth's orbit , and atmospheric composition. The scientific consensus[4] is that most of the warming observed since the mid-twentieth century is very likely due to increased atmospheric concentrations of greenhouse gases produced by human activity. Some other hypotheses have been offered to explain most of the observed increase in global temperatures but these are not broadly supported in the scientific community. This is just another version of the typical "consensus" argument which was responsible for past conclusions that all matter was made of four elements, earth, air, fire and water as well as the common beliefs that the Earth was flat and that the sun and other planets in the solar system revolved around the Earth. One sure sign that compelling arguments are unavailable is reliance on consensus arguments. The simple fact is that there is compelling evidence that warming and cooling cycles are caused by natural fluctuations in the climate, that warming is mainly a result of variations in solar radiation,[5] or that warming is caused by changes in cloud cover due to variations in galactic cosmic rays.[6] Despite claims by some that such ideas are not well supported in the scientific community CERN found it reasonable to devote signficant resources to a major experiment regarding the influence of solar variation on cosmic rays, cloud formation and resulting global warming or cooling.

The effects of forcing are not instantaneous. Due to the thermal inertia of the oceans and the slow responses of some feedback processes, Earth's climate is never in perfect equilibrium with the imposed forcing. Climate commitment studies indicate that even if greenhouse gases were stabilized at present day levels there would be a further warming of about 0.5 °C (0.9 °F) as the climate continued to adjust toward equilibrium.[7]

Greenhouse gases in the atmosphere

Existence of the greenhouse effect itself is not disputed. It is the process by which emission of infrared radiation by atmospheric gases warms a planet's atmosphere and surface. Naturally occurring greenhouse gases warm the Earth by about 33 °C (59 °F). Without this natural greenhouse effect, the average temperature of Earth would be about -18 °C (0 °F) making the planet uninhabitable.[8] The major natural greenhouse gases are water vapor, which causes about 36–70% of the greenhouse effect (not including clouds); carbon dioxide (CO2), which causes 9–26%; methane (CH4), which causes 4–9%; and ozone, which causes 3–7%.[9]

The main issues are whether or not carbon dioxide causes or comes from increased global temperatures and whether or not it actually plays a measurable role in climate change as suggested. Proponents of catastrophic anthropogenic climate change alarmism theories always had difficulty explaining how the estimated 1/20 anthropogenic contribution to the carbon cycle dominated the 19/20 natural contribution and were dogged by more careful and detailed studies of available evidence which suggested conclusions regarding historic atmospheric carbon dioxide levels were erroneous and that modern day atmospheric carbon dioxide increases were driven not by man but by an easily explained process involving known upwelling of cold, deep, carbon dioxide rich ocean water and subsequent well understood outgassing as those waters were heated.[14]

The present atmospheric concentration of CO2 is about 383 parts per million (ppm) by volume.[10] From geological evidence it is believed that CO2 values this high were last attained 20 million years ago.[11] About three-fourths of man-made CO2 emissions over the past 20 years have come from the burning of fossil fuels. Most of the rest is due to land-use change, mainly deforestation.[12] Measured trends in atmospheric composition and isotope ratios (namely the simultaneous depletion of 13C, 14C, and O2) confirm that the increased atmospheric CO2 mainly comes from fossil fuels and not from other sources such as volcanoes or the oceans.[13]

Future CO2 concentrations will depend on uncertain economic, sociological, technological, and natural developments. If the years since Kyoto are any guide we can expect lots of talk but little actual concrete action. Since emissions have continued to climb at ever increasing rates yet climate seems to have levelled off or even to have entered a cooling phase we may soon see some interesting reconsideration of what some have referred to as "settled" science. The IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios gives a wide range of future CO2 scenarios, ranging from 541 to 970 ppm by the year 2100.[14] Fossil fuel reserves are sufficient to reach these levels and continue emissions past 2100, if coal, tar sands, or methane clathrates are extensively used.[15] Positive feedback effects such as the release of methane from the melting of permafrost peat bogs in Siberia (possibly up to 70,000 million tonnes) may lead to significant additional sources of greenhouse gas emissions[16] not included in climate models cited by the IPCC.[2]

Feedbacks

Catastrophic anthropogenic climate change alarmism suggests that climate feedback processes tend to all be positive. Indeed they must be programmed that way, well beyond anything actually found in nature, in climate models in order to produce the sort of rampant warming scenarios most often featured in IPCC announcments and sensationalized media reports. The problem with this scenario is simple. We know from geological and other evidence that the Earth has experienced significant periods of much warmer and much colder climate yet it always reverts back. If climate processes featured such overwhelmingly reinforcing feedbacks as alarmist theories suggest there is simply no way climate, once it embarked on a path of significant warming or cooling, could reverse and therefore life as we know it would not exist. Experience teaches us that feedback mechanisms necessary to support theories that attribute any signficiant portion of global warming to anthropogenic emissions require those mechanisms to be grossly overstated and sometimes to have the reverse effect than that actually observed in the real world. Removing the grossly overestimated and improperly signed feedback parameters from climate models might allow for the removal of other unnatural checks and balances necessarily built into them to prevent the models from automatically going into runaway scenarios.

The effects of forcing agents on the climate are modified by feedback processes. One of the most important feedbacks is caused by the evaporation of water. Increased greenhouse gases from human activity cause a warming of the Earth's atmosphere and surface. The increased warmth in turn increases the evaporation of water into the atmosphere. Since water vapor itself is a greenhouse gas, this causes still more warming; the warming causes more water vapor to be evaporated, and so on. Eventually a new dynamic equilibrium concentration of water vapor is reached at a slight increase in humidity and with a much larger greenhouse effect than that due to CO2 alone.[17]

The radiative effects of clouds are a major source of uncertainty in climate projections. Seen from below, clouds emit infrared radiation to the surface, and so have a warming effect. Seen from above, clouds reflect sunlight and emit infrared radiation to space, and so have a cooling effect. The cloud feedback effect is influenced not only by the amount of clouds but also by their distribution; for example, high clouds are at colder temperatures than low clouds, and thus radiate less energy to space. Increased global water vapor content may or may not cause an increase in global or regional cloud cover, since cloud cover is affected by relative humidity rather than the absolute concentration of water vapor. Cloud feedback is second only to water vapor feedback and has been found to have a net warming effect in all the models that contributed to the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report.[17]

Another important process is ice-albedo feedback.[18] Warming of the Earth's surface leads to melting of ice near the poles. As the ice melts, land or open water takes its place. Both land and open water are on average less reflective than ice, and thus absorb more solar radiation. This causes more warming, which in turn causes more melting, and the cycle continues.

The ocean's ability to sequester carbon is expected to decline as it warms, because the resulting low nutrient levels of the mesopelagic zone limits the growth of diatoms in favor of smaller phytoplankton that are poorer biological pumps of carbon.[19]

Solar variation

It has been hypothesized that variations in solar output, possibly amplified by cloud feedbacks, may have been a secondary contributor to recent warming.[20] Natural phenomena, such as solar variation and volcanoes, probably had a net warming effect from pre-industrial times to 1950 and a small cooling effect since 1950.[21] Some research indicate that the Sun's contribution may have been underestimated. These results suggest that the Sun may have contributed about 40–50% of the global surface warming between 1900 and 2000 and about 25–35% of the warming between 1980 and 2000.[22] Stott and coauthors suggest that climate models overestimate the relative effect of greenhouse gases compared to solar forcing; they also suggest that the cooling effects of volcanic dust and sulfate aerosols have been underestimated.[23] Nevertheless, they conclude that even with an enhanced climate sensitivity to solar forcing, most of the warming during the latest decades is attributable to the increases in greenhouse gases.

Climate change since the Industrial Revolution

According to the instrumental temperature record, mean global temperatures (both land and sea) have increased by 0.75 °C (1.35 °F) relative to the period 1860–1900. This measured temperature increase is not significantly affected by the urban heat island effect.[24][25][26] Since 1979, land temperatures have increased about twice as fast as ocean temperatures (0.25 °C per decade against 0.13 °C per decade).[27] Temperatures in the lower troposphere have increased between 0.12 and 0.22 °C (0.22 and 0.4 °F) per decade since 1979, according to satellite temperature measurements. Temperature is believed to have been relatively stable over the one or two thousand years before 1850, with possibly regional fluctuations such as the Medieval Warm Period or the Little Ice Age.

Based on estimates by NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, 2005 was the warmest year since reliable, widespread instrumental measurements became available in the late 1800s, exceeding the previous record set in 1998 by a few hundredths of a degree.[28] Estimates prepared by the World Meteorological Organization and the Climatic Research Unit concluded that 2005 was the second warmest year, behind 1998.[29][30] Global temperatures in 1998 were exceptionally warm because the strongest El Niño in the instrumental record occurred in that year.[31]

Anthropogenic emissions of other pollutants—notably sulfate aerosols—can exert a cooling effect by increasing the reflection of incoming sunlight. This partially accounts for the cooling seen in the temperature record in the middle of the twentieth century,[32] though the cooling may also be due in part to natural variability.

Still unexplained is the fact that even as emissions of anthropogenic greenhouse gasses accelerate at an accelerating rate, 1998 remains "the hottest year ever" and global temperatures seem to be in either a holding pattern or may even be showing signs of declining. In 1998 the "proof" of unusual global warming that could only be attributed to human causes involved the unusually warm sea surface waters in the Pacific known as El Nino. Interestingly enough now that those same waters are unusually cool you don't hear similar claims it is equal proof of global cooling today.

Climate models

Scientists have studied global warming with computer models of the climate. These models are based on physical principles of fluid dynamics, radiative transfer, and other processes, with some simplifications being necessary because of limitations in computer power. These models predict that the net effect of adding greenhouse gases is to produce a warmer climate. However, even when the same assumptions of fossil fuel consumption and CO2 emission are used, the amount of projected warming varies between models and there is a considerable range of climate sensitivity. Including uncertainties in future greenhouse gas concentrations and climate modeling, the IPCC report projects a warming of 1.1 °C to 6.4 °C (2.0 °F to 11.5 °F) between 1990 and 2100.[2]

Models have also been used to help investigate the causes of recent climate change by comparing the observed changes to those that the models project from various natural and human derived causes. Climate models can produce a good match to observations of global temperature changes over the last century, but cannot yet simulate all aspects of climate.[33] These models do not unambiguously attribute the warming that occurred from approximately 1910 to 1945 to either natural variation or human effects; however, they suggest that the warming since 1975 is dominated by man-made greenhouse gas emissions.

Global climate model projections of future climate are forced by imposed greenhouse gas scenarios, generally one from the IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios (SRES). Less commonly, models may also include a simulation of the carbon cycle; this generally shows a positive feedback, though this response is uncertain (under the A2 SRES scenario, responses vary between an extra 20 and 200 ppm of CO2). Some observational studies also show a positive feedback.[34][35][36]

The representation of clouds is one of the main sources of uncertainty in present-generation models, though progress is being made on this problem.[37] There is also an ongoing discussion as to whether climate models are neglecting important indirect and feedback effects of solar variability.

The most interesting note about climate models is the fact that none of them agree nor do any of them come close to producing long-term realistic predictions with regards to both temperature and precipitation at the same time. Interestingly enough the IPCC takes all the known wrong answers, sums them together then blesses the result as valid.

Attributed and expected effects

Some effects on both the natural environment and human life are, at least in part, already being attributed to global warming. A 2001 report by the IPCC suggests that glacier retreat, ice shelf disruption such as the Larsen Ice Shelf, sea level rise, changes in rainfall patterns, and increased intensity and frequency of extreme weather events, are being attributed in part to global warming.[38] While changes are expected for overall patterns, intensity, and frequencies, it is difficult to attribute specific events to global warming. Other expected effects as a result of warmer temperatures include water scarcity in some regions and increased precipitation in others, changes in mountain snowpack, and adverse health effects.

Increasing deaths, displacements, and economic losses projected due to extreme weather attributed to global warming may be exacerbated by growing population densities in affected areas, although temperate regions are projected to experience some minor benefits, such as fewer deaths due to cold exposure.[39] A summary of probable effects and recent understanding can be found in the report made for the IPCC Third Assessment Report by Working Group II.[38] The newer IPCC Fourth Assessment Report summary reports that there is observational evidence for an increase in intense tropical cyclone activity in the North Atlantic Ocean since about 1970, in correlation with the increase in sea surface temperature, but that the detection of long-term trends is complicated by the quality of records prior to routine satellite observations. The summary also states that there is no clear trend in the annual worldwide number of tropical cyclones.[2]

Additional anticipated effects include sea level rise of 110 to 770 millimeters (0.36 to 2.5 ft) between 1990 and 2100,[40] repercussions to agriculture, possible slowing of the thermohaline circulation, reductions in the ozone layer, increased intensity and frequency of hurricanes and extreme weather events, lowering of ocean pH, and the spread of diseases such as malaria and dengue fever. One study predicts 18% to 35% of a sample of 1,103 animal and plant species would be extinct by 2050, based on future climate projections.[41] McLaughlin et al. have documented two populations of Bay checkerspot butterfly being threatened by precipitation change, though they state few mechanistic studies have documented extinctions due to recent climate change.[42]

Mitigation and adaptation

The broad agreement among climate scientists that global temperatures will continue to increase has led nations, states, corporations, and individuals to implement actions to try to curtail global warming or adjust to it. Many environmental groups encourage action against global warming, often by the consumer, but also by community and regional organizations. There has been business action on climate change, including efforts at increased energy efficiency and (still limited) moves to alternative fuels. One innovation has been the development of greenhouse gas emissions trading through which companies, in conjunction with government, agree to cap their emissions or to purchase credits from those below their allowances.

The world's primary international agreement on combating global warming is the Kyoto Protocol, an amendment to the UNFCCC, negotiated in 1997. The Protocol now covers more than 160 countries globally and over 55% of global greenhouse gas emissions.[43] The United States and Kazakhstan have not ratified the treaty. China and India, two other large emitters, have ratified the treaty but, as developing countries, are exempt from its provisions. This treaty expires in 2012, and international talks began in May 2007 on a future treaty to succeed the current one.[44]

The world's primary body for crafting a response is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), a UN-sponsored activity which holds periodic meetings between national delegations on the problems of global warming, and issues working papers and assessments on the current status of the science of climate change, impacts, and mitigation. It convenes four different working groups examining various specific issues.

Related climatic issues

A variety of issues are often raised in relation to global warming. One is ocean acidification. Increased atmospheric CO2 increases the amount of CO2 dissolved in the oceans.[45] CO2 dissolved in the ocean reacts with water to form carbonic acid resulting in acidification. Ocean surface pH is estimated to have decreased from approximately 8.25 to 8.14 since the beginning of the industrial era.[46] The key word here is "surface", keeping in mind that the surface of the ocean accounts for a miniscule portion of the total ocean volume. Plus as the surface of the ocean warms known physical processes drive dissolved carbon dioxide out of solution, suggesting theories of ever decreasing pH due to increasing dissolved carbon dioxide gas are flawed. Nevertheless, it is estimated that it will drop by a further 0.14 to 0.5 units by 2100 as the ocean absorbs more CO2.[2][47] Note that this is between two and five times the suggested present observed change and it is projected to occur over signficantly less time. As with past IPCC and general alarmist predictions which never managed to come true this one will have to be seen to be believed. Since organisms and ecosystems are adapted to a narrow range of pH, this raises extinction concerns, directly driven by increased atmospheric CO2, that could disrupt food webs and impact human societies that depend on marine ecosystem services except for the fact that the observed and any reasonably projected future changes are still within those narrow ranges, of course. [48]

Another related issue that may have partially mitigated global warming in the late twentieth century is global dimming, the gradual reduction in the amount of global direct irradiance at the Earth's surface. From 1960 to 1990, human-caused aerosols likely precipitated this effect. Scientists have stated with 66–90% confidence that the effects of human-caused aerosols, along with volcanic activity, have offset some of global warming, and that greenhouse gases would have resulted in more warming than observed if not for these dimming agents.[2]

References

- ↑ http://nationalacademies.org/onpi/06072005.pdf

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 Summary for Policymakers (PDF). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007-02-05). Retrieved on 2007-02-02.

- ↑ United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, Article I. United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-01-15.

- ↑ Joint science academies' statement: The science of climate change (ASP). Royal Society (2001-05-17). Retrieved on 2007-04-01. “The work of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) represents the consensus of the international scientific community on climate change science”

- ↑ Bard, Edouard; Frank, Martin (2006-06-09). "Climate change and solar variability: What's new under the sun?". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 248 (1-2): 1-14. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- ↑ Svensmark, Henrik (July 2000). "Cosmic Rays and Earth's Climate" (PDF). Space Science Reviews 93 (1-2): 175-185. Retrieved on 2007-09-17.

- ↑ Meehl, Gerald A.; et al. (2005-03-18). "How Much More Global Warming and Sea Level Rise". Science 307 (5716): 1769–1772. DOI:10.1126/science.1106663. Retrieved on 2007-02-11. Research Blogging.

- ↑ (December 2002). Living with Climate Change – An Overview of Potential Climate Change Impacts on Australia. Summary and Outlook (PDF). Australian Greenhouse Office. Retrieved on 2007-04-18.

- ↑ Kiehl, J. T.; Kevin E. Trenberth (February 1997). "Earth’s Annual Global Mean Energy Budget" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Meteorological Society 78 (2): 197-208. Retrieved on 2006-05-01.

- ↑ Tans, Pieter. Trends in Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide – Mauna Loa. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ Pearson, Paul N.; Palmer, Martin R. (2000-08-17). "Atmospheric carbon dioxide concentrations over the past 60 million years". Nature 406 (6797): 695–699. DOI:10.1038/35021000. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001-01-20). Retrieved on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ Prentice, I. Colin; et al. (2001-01-20). 3.7.3.3 SRES scenarios and their implications for future CO2 concentration. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ 4.4.6. Resource Availability. IPCC Special Report on Emissions Scenarios. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ Sample, Ian. Warming Hits 'Tipping Point', The Guardian, 2005-08-11. Retrieved on 2007-01-18.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Soden, Brian J.; Held, Isacc M. (2005-11-01). "An Assessment of Climate Feedbacks in Coupled Ocean–Atmosphere Models" (PDF). Journal of Climate 19 (14). Retrieved on 2007-04-21. “Interestingly, the true feedback is consistently weaker than the constant relative humidity value, implying a small but robust reduction in relative humidity in all models on average" "clouds appear to provide a positive feedback in all models”

- ↑ Stocker, Thomas F.; et al. (2001-01-20). 7.5.2 Sea Ice. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-02-11.

- ↑ Buesseler, K.O., C.H. Lamborg, P.W. Boyd, P.J. Lam, T.W. Trull, R.R. Bidigare, J.K.B. Bishop, K.L. Casciotti, F. Dehairs, M. Elskens, M. Honda, D.M. Karl, D.A. Siegel, M.W. Silver, D.K. Steinberg, J. Valdes, B. Van Mooy, S. Wilson. (2007) "Revisiting carbon flux through the ocean's twilight zone." Science 316: 567-570.

- ↑ Marsh, Nigel; Henrik, Svensmark (November 2000). "Cosmic Rays, Clouds, and Climate" (PDF). Space Science Reviews 94: 215–230. DOI:10.1023/A:1026723423896. Retrieved on 2007-04-17. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Hegerl, Gabriele C.; et al. (2007-05-07). Understanding and Attributing Climate Change (PDF). Climate Change 2007: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fourth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change 690. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-05-20.

- ↑ Scafetta, Nicola; West, Bruce J. (2006-03-09). "Phenomenological solar contribution to the 1900–2000 global surface warming" (PDF). Geophysical Research Letters 33 (5). DOI:10.1029/2005GL025539. L05708. Retrieved on 2007-05-08. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Stott, Peter A.; et al. (2003-12-03). "Do Models Underestimate the Solar Contribution to Recent Climate Change?". Journal of Climate 16 (24): 4079–4093. DOI:10.1175/1520-0442(2003)016%3C4079:DMUTSC%3E2.0.CO;2. Retrieved on 2007-04-16. Research Blogging.

- ↑ David E. Parker (2004). "Climate: Large-scale warming is not urban". Nature 432: 290. [http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v432/n7015/abs/432290a.html

- ↑ David E. Parker (2006). "A demonstration that large-scale warming is not urban". Journal of Climate 19: 2882–2895. [2](online)]

- ↑ Thomas C. Peterson (2003). "Assessment of urban versus rural in situ surface temperatures in the contiguous United States: no difference found". Journal of Climate 16: 2941–2959. (PDF)

- ↑ Smith, Thomas M.; Reynolds, Richard W. (2005-05-15). "A Global Merged Land–Air–Sea Surface Temperature Reconstruction Based on Historical Observations (1880–1997)" (PDF). Journal of Climate 18 (12): 2021–2036. Retrieved on 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Hansen, James E.; et al. (2006-01-12). Goddard Institute for Space Studies, GISS Surface Temperature Analysis. NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies. Retrieved on 2007-01-17.

- ↑ Global Temperature for 2005: second warmest year on record (PDF). Climatic Research Unit, School of Environmental Sciences, University of East Anglia (2005-12-15). Retrieved on 2007-04-13.

- ↑ WMO STATEMENT ON THE STATUS OF THE GLOBAL CLIMATE IN 2005 (PDF). World Meteorological Organization (2005-12-15). Retrieved on 2007-04-13.

- ↑ National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration: Global Warming Frequently Asked Questions

- ↑ Mitchell, J. F. B.; et al. (2001-01-20). 12.4.3.3 Space-time studies. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-01-04.

- ↑ Summary for Policymakers. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001-01-20). Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ Torn, Margaret; Harte, John (2006-05-26). "Missing feedbacks, asymmetric uncertainties, and the underestimation of future warming". Geophysical Research Letters 33 (10). L10703. Retrieved on 2007-03-04.

- ↑ Harte, John; et al. (2006-10-30). "Shifts in plant dominance control carbon-cycle responses to experimental warming and widespread drought". Environmental Research Letters 1 (1). 014001. Retrieved on 2007-05-02.

- ↑ Scheffer, Marten; et al. (2006-05-26). "Positive feedback between global warming and atmospheric CO2 concentration inferred from past climate change.". Geophysical Research Letters 33. DOI:10.1029/2005gl025044. Retrieved on 2007-05-04. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Stocker, Thomas F.; et al. (2001-01-20). 7.2.2 Cloud Processes and Feedbacks. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2007-03-04.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 Climate Change 2001: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2001-02-16). Retrieved on 2007-03-14.

- ↑ Summary for Policymakers (PDF). Climate Change 2007: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Working Group II Contribution to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change Fourth Assessment Report. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (2007-04-13). Retrieved on 2007-04-28.

- ↑ Church, John A.; et al. (2001-01-20). Executive Summary of Chapter 11. Climate Change 2001: The Scientific Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Third Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. Retrieved on 2005-12-19.

- ↑ Thomas, Chris D.; et al. (2004-01-08). "Extinction risk from climate change" (PDF). Nature 427 (6970): 145-138. DOI:10.1038/nature02121. Retrieved on 2007-03-18. Research Blogging.

- ↑ McLaughlin, John F.; et al. (2002-04-30). "Climate change hastens population extinctions" (PDF). PNAS 99 (9): 6070–6074. DOI:10.1073/pnas.052131199. Retrieved on 2007-03-29. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Kyoto Protocol Status of Ratification (PDF). United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2006-07-10). Retrieved on 2007-04-27.

- ↑ Climate talks face international hurdles, by Arthur Max, Associated press, 5/14/07.

- ↑ The Ocean and the Carbon Cycle. NASA (2005-06-21). Retrieved on 2007-03-04.

- ↑ Jacobson, Mark Z. (2005-04-02). "Studying ocean acidification with conservative, stable numerical schemes for nonequilibrium air-ocean exchange and ocean equilibrium chemistry" (PDF). Journal of Geophysical Research 110 (D7). DOI:10.1029/2004JD005220. D07302. Retrieved on 2007-04-28. Research Blogging.

- ↑ Caldeira, Ken; Wickett, Michael E. (2005-09-21). "Ocean model predictions of chemistry changes from carbon dioxide emissions to the atmosphere and ocean". Journal of Geophysical Research 110 (C09S04): 1–12. Retrieved on 2006-02-14.

- ↑ Raven, John A.; et al. (2005-06-30). Ocean acidification due to increasing atmospheric carbon dioxide (ASP). Royal Society. Retrieved on 2007-05-04.

Further reading

- Amstrup, Steven C.; Ian Stirling, Tom S. Smith, Craig Perham, Gregory W. Thiemann (2006-04-27). "Recent observations of intraspecific predation and cannibalism among polar bears in the southern Beaufort Sea". Polar Biology 29 (11): 997–1002. DOI:10.1007/s00300-006-0142-5. Research Blogging.

- Association of British Insurers (2005-06). Financial Risks of Climate Change (PDF).

- Barnett, Tim P.; J. C. Adam, D. P. Lettenmaier (2005-11-17). "Potential impacts of a warming climate on water availability in snow-dominated regions". Nature 438 (7066): 303–309. DOI:10.1038/nature04141. Research Blogging.

- Behrenfeld, Michael J.; Robert T. O'Malley, David A. Siegel, Charles R. McClain, Jorge L. Sarmiento, Gene C. Feldman, Allen G. Milligan, Paul G. Falkowski, Ricardo M. Letelier, Emanuel S. Boss (2006-12-07). "Climate-driven trends in contemporary ocean productivity" (PDF). Nature 444 (7120): 752–755. DOI:10.1038/nature05317. Research Blogging.

- Choi, Onelack; Ann Fisher (May 2005). "The Impacts of Socioeconomic Development and Climate Change on Severe Weather Catastrophe Losses: Mid-Atlantic Region (MAR) and the U.S.". Climate Change 58 (1–2): 149–170. DOI:10.1023/A:1023459216609. Research Blogging.

- Dyurgerov, Mark B.; Mark F. Meier (2005). Glaciers and the Changing Earth System: a 2004 Snapshot (PDF). Institute of Arctic and Alpine Research Occasional Paper #58.

- Emanuel, Kerry A. (2005-08-04). "Increasing destructiveness of tropical cyclones over the past 30 years." (PDF). Nature 436 (7051): 686–688. DOI:10.1038/nature03906. Research Blogging.

- Hansen, James; Larissa Nazarenko, Reto Ruedy, Makiko Sato, Josh Willis, Anthony Del Genio, Dorothy Koch, Andrew Lacis, Ken Lo, Surabi Menon, Tica Novakov, Judith Perlwitz, Gary Russell, Gavin A. Schmidt, Nicholas Tausnev (2005-06-03). "Earth's Energy Imbalance: Confirmation and Implications" (PDF). Science 308 (5727): 1431–1435. DOI:10.1126/science.1110252. Research Blogging.

- Hinrichs, Kai-Uwe; Laura R. Hmelo, Sean P. Sylva (2003-02-21). "Molecular Fossil Record of Elevated Methane Levels in Late Pleistocene Coastal Waters". Science 299 (5610): 1214–1217. DOI:10.1126/science.1079601. Research Blogging.

- Hirsch, Tim. Plants revealed as methane source, BBC, 2006-01-11.

- Hoyt, Douglas V.; Kenneth H. Schatten (1993–11). "A discussion of plausible solar irradiance variations, 1700–1992". Journal of Geophysical Research 98 (A11): 18,895–18,906.

- Kenneth, James P.; Kevin G. Cannariato, Ingrid L. Hendy, Richard J. Behl (2003-02-14). Methane Hydrates in Quaternary Climate Change: The Clathrate Gun Hypothesis. American Geophysical Union.

- Keppler, Frank, Marc Brass, Jack Hamilton, Thomas Röckmann. Global Warming - The Blame Is not with the Plants, Max Planck Society, 2006-01-18.

- Kurzweil, Raymond (2006–07). "Nanotech Could Give Global Warming a Big Chill" (PDF). Forbes / Wolfe Nanotech Report 5 (7).

- Lean, Judith L.; Y.M. Wang, N.R. Sheeley (2002–12). "The effect of increasing solar activity on the Sun's total and open magnetic flux during multiple cycles: Implications for solar forcing of climate". Geophysical Research Letters 29 (24). DOI:10.1029/2002GL015880. Research Blogging.

- Lerner, K. Lee; Brenda Wilmoth Lerner (2006-07-26). Environmental issues : essential primary sources.. Thomson Gale. ISBN 1414406258.

- McLaughlin, Joseph B.; Angelo DePaola, Cheryl A. Bopp, Karen A. Martinek, Nancy P. Napolilli, Christine G. Allison, Shelley L. Murray, Eric C. Thompson, Michele M. Bird, John P. Middaugh (2005-10-06). "Outbreak of Vibrio parahaemolyticus gastroenteritis associated with Alaskan oysters". New England Journal of Medicine 353 (14): 1463–1470.

(online version requires registration)

- Muscheler, Raimund; Fortunat Joos, Simon A. Müller, Ian Snowball (2005-07-28). "Climate: How unusual is today's solar activity?" (PDF). Nature 436 (7012): 1084–1087. DOI:10.1038/nature04045. Research Blogging.

- Oerlemans, J. (2005-04-29). "Extracting a Climate Signal from 169 Glacier Records" (PDF). Science 308 (5722): 675–677. DOI:10.1126/science.1107046. Research Blogging.

- Oreskes, Naomi (2004-12-03). "Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change" (PDF). Science 306 (5702): 1686. DOI:10.1126/science.1103618. Research Blogging.

- Purse, Bethan V.; Philip S. Mellor, David J. Rogers, Alan R. Samuel, Peter P. C. Mertens, Matthew Baylis (February 2005). "Climate change and the recent emergence of bluetongue in Europe". Nature Reviews Microbiology 3 (2): 171–181. DOI:10.1038/nrmicro1090. Research Blogging.

- Revkin, Andrew C. Rise in Gases Unmatched by a History in Ancient Ice, The New York Times, 2005-11-05.

- Ruddiman, William F. (2005-12-15). Earth's Climate Past and Future. New York: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-7167-3741-8.

- Ruddiman, William F. (2005-08-01). Plows, Plagues, and Petroleum: How Humans Took Control of Climate. New Jersey: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-12164-8.

- Solanki, Sami K.; I.G. Usoskin, B. Kromer, M. Schussler, J. Beer (2004-10-23). "Unusual activity of the Sun during recent decades compared to the previous 11,000 years." (PDF). Nature 431: 1084–1087. DOI:10.1038/nature02995. Research Blogging.

- Solanki, Sami K.; I. G. Usoskin, B. Kromer, M. Schüssler, J. Beer (2005-07-28). "Climate: How unusual is today's solar activity? (Reply)" (PDF). Nature 436: E4-E5. DOI:10.1038/nature04046. Research Blogging.

- Sowers, Todd (2006-02-10). "Late Quaternary Atmospheric CH4 Isotope Record Suggests Marine Clathrates Are Stable". Science 311 (5762): 838–840. DOI:10.1126/science.1121235. Research Blogging.

- Svensmark, Henrik; Jens Olaf P. Pedersen, Nigel D. Marsh, Martin B. Enghoff, Ulrik I. Uuggerhøj (2007-02-08). "Experimental evidence for the role of ions in particle nucleation under atmospheric conditions". Proceedings of the Royal Society A 463 (2078): 385–396. DOI:10.1098/rspa.2006.1773. Research Blogging.

(online version requires registration)

- Walter, K. M.; S. A. Zimov, Jeff P. Chanton, D. Verbyla, F. S. Chapin (2006-09-07). "Methane bubbling from Siberian thaw lakes as a positive feedback to climate warming". Nature 443 (7107): 71–75. DOI:10.1038/nature05040. Research Blogging.

- Wang, Y.-M.; J.L. Lean, N.R. Sheeley (2005-05-20). "Modeling the sun's magnetic field and irradiance since 1713" (PDF). Astrophysical Journal 625: 522–538. DOI:10.1086/429689. Research Blogging.

External links

Scientific

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC)

- Nature Reports Climate Change

- NOAA's Global Warming FAQ

- Outgoing Longwave Radiation pentad mean - NOAA Climate Prediction Center

- Discovery of Global Warming — An extensive introduction to the topic and the history of its discovery

- Caution urged on climate 'risks'

- NASA Finds Sun-Climate Connection in Old Nile Records

- News in Science - Night flights are worse for global warming - 15/06/2006

Educational

- What Is Global Warming? Simulation from National Geographic

- The EdGCM (Educational Global Climate Modelling) Project free research-quality simulation for students, educators, and scientists alike, with a user-friendly interface that runs on desktop computers

- Daily global temperatures and trends from satellites Interactive graphics from NASA

- The Pew Center on global climate change

Other

- The Global Warming Survival Guide from Time.com

- UBS Launches First Global Warming Index "UBS-GWI"

- Global Warming News & Articles Portal

- UN: rearing cattle produces more greenhouse gases than driving cars

- Science and Technology Librarianship: Global Warming and Climate Change Science – Extensive commented list of Internet resources – Science and Technology Sources on the Internet.

- Union of Concerned Scientists Global Warming page

- Watch and read 'Tipping Point', Australian science documentary about effects of global warming on rare, common, and endangered wildlife

- Newest reports on U.S. EPA website

- IPS Inter Press Service — Independent news on global warming and its consequences.

- Indonesia Counts Its Islands Before It Is Too Late

- World Environment Day 2007 "Melting Ice" image gallery at The Guardian

- Climate Counts - corporate watchdog