Infant colic: Difference between revisions

imported>Aleksander Stos m (typo) |

imported>Robert W King No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | |||

<!-- [[Category:Health Sciences Workgroup]] --> | <!-- [[Category:Health Sciences Workgroup]] --> | ||

Most recent approved version: [[Infant colic]] | Most recent approved version: [[Infant colic]] | ||

Revision as of 21:47, 13 January 2008

Most recent approved version: Infant colic

Infant colic is a medical term for persistent and inconsolable crying by healthy infants, who are usually between the ages of two and sixteen weeks. It is a syndrome – a defined set of symptoms and signs – and not a specific disease. The most accepted definition is: continuous crying that lasts for a period of more than three hours, occurring more than three days per week, and continuing for longer than three weeks.[1]

"Infant colic" (or "colic") applies only to young infants, and does not include older babies and toddlers who may cry excessively. When infant colic occurs in full-term babies, it starts by two weeks of age and subsides by age four months. The onset in premature infants is delayed by the duration of prematurity, that is, if the baby was born three weeks prematurely, infant colic starts five (three plus two) weeks after birth, and may last until near five months of age (four months plus three weeks).

What is colic? In Medicine, a cramp-like pain that arises from a hollow organ (like the uterus or intestine) is called a "colicky" pain, and in Veterinary science, "colic" is a serious disorder in horses that is not only painful - but usually requires emergency surgery. The Oxford English dictionary's first definition of the word colic (as a noun) is: "A name given to severe paroxysmal griping pains in the belly, due to various affections of the bowels or other parts; also to the affections of which such pains are the characteristic symptom". How did infant colic get its name? Is there a problem with the baby's intestine? Is the baby having severe cramping pain? The answer seems to be "no", as far as can be told, in infant colic the actual medical cause for the excessive crying is not known. The use of the word colic apparently originated from the interpretation of the baby's cry and body positions, suggesting a painful intestinal conditional to adult onlookers - and so the term "colic" is likely to be a misnomer.

Indeed, as far as scientific medicine is concerned, infant colic is a syndrome which has no known cause, no known harmful effects (other than that on the parents, which may - unfortunately - be reflected onto the baby, with potentially disastrous consequences[2]), and no specific treatment. Self-limited, it begins and ends by itself. Given such vagueness, and the absence of any known cause or ill effect, there is some dispute that infant colic even exists as a true medical disorder.[3] In other words, there is no doubt that a group of infants have this syndrome, the doubt concerns whether or not there is anything wrong with them, medically or otherwise. The phenomenon that some babies at certain ages cry excessively may be a non-specific response to any number of stimuli, and the crying as such may have no significance as indicating a disease, nor is it a disease itself. It may simply be something that some perfectly normal babies do very easily and often at that time of their lives. If that is the case, a "cause" and a "cure" for infant colic will not be found, but the idea that the syndrome itself is not an indication of disease would be a reassurance to parents.

The reader should not infer that this condition is entirely innocent or inconsequential. While the crying, as such, is no direct threat to the baby’s health, it can certainly undermine the infant's growth and development indirectly. Persistent distress that is triggered in parents and other children may have serious consequences for the baby's immediate physical well-being, intra-family relationships, and future attitudes towards the child.[4][5] Infant colic has been identified as a significant risk for the Shaken baby syndrome.[6][7] When series of mothers of colicky babies have been interviewed by researchers in studies, up to 70% of the mothers of very colicky babies admit to having had explicitly aggressive thoughts towards the crying child, while 26% have even been troubled by fantasies of infanticide.[2] This cannot be taken lightly.

This article sets out to describe what is meant by the complaint, what is known about possible causes, what treatments may be used, and what the short- and long-term consequences of the condition may be.

A closer look at the signs & symptoms

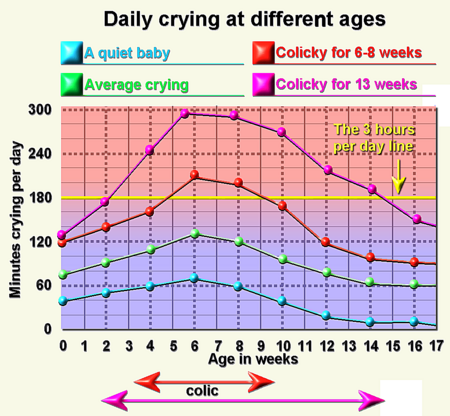

The vertical divisions represent age divisions in weeks. The horizontal dotted lines represent 60 minute intervals (the thin solid ones are 20 min divisions). The yellow line indicates the 180 min/day which Wessel et al used as one criterion for diagnosing "seriously fussy" (colicky) in their seminal paper.[1] Apart from being an attempt to ensure that different researchers are studying the same phenomenon, this line has no implications with regard to health status or normality of the infant.

The green "average" line is read as follows: In the first week of life (0 to 1 on the bottom horizontal axis) the crying lasts for approximately 40 mins per day, in the 6th week, 130 mins, and in the 16th week 60 mins - these figures are obtained by locating the week on the bottom line, following the vertical division line up to where it intersects the green line, and then going horizontally to the left, to locate the crying time value which corresponds to that point. Note the transitional coloring between the blue (no colic) and light red (colic) backgrounds. This has been done specifically to indicate that there is a mixed "no colic"/"colic" area, where a baby (in the opinion of the parent) may be colicky or may not be, irrespective of whether the duration per day is less or more than 180 mins. The double headed arrows at the bottom indicate the weeks during which babies on the red and the purple curves would be considered by researchers to have colic.

Normally a baby starts crying at birth, with awake time being divided between feeding, lying still, learning to use its muscles and senses, "fussing", and crying. Crying follows two patterns in time, the one is a typical variation of daily crying times over the first 3 to 6 months of life, and the second is a diurnal rhythm, characterised by increased crying in the late afternoon and evening.[8]

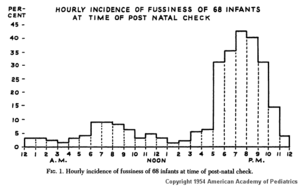

Figures 1, 2 and 3 depict different aspects of normal and problem crying. Figure 2, The crying hours shows how crying is distributed in a 24 hour period, midnight to midnight; the increased occurrence during the late afternoon and first half of the evening is clear. This pattern is typical for all societies studied, and is most obvious at the time when the total crying time peaks - around six weeks after birth - but the mechanism for this rhythm has not been elucidated. In a modern family, with both parents working, the diurnal peak coincides most unfortunately with the time that the parents return from work, and wish to spend a pleasant time with the rest of the family. This may partly explain the degree of frustration and anger suffered by parents of colicky infants, and the correlation with incidents of shaken baby syndrome.

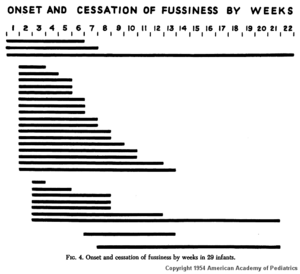

Figure 3, The crying weeks, shows the individual starting age, duration, and end age for each one of 29 colicky ("seriously fussy") babies, represented by a horizontal bar graph, as determined by Wessel et al in 1954. It does not show the amount of excess crying, nor how the crying increases and decreases from day to day. The relationship of excessive crying to normal or marginally excessive crying cannot be appreciated from the graph. In this regard, the graph on the right (figure 1: Crying curves) is more informative. This normal infant crying curve was elucidated by pediatrician T Berry Brazelton in 1962.[9] The duration of daily crying - the sum of the times of individual crying episodes over 24 hours - is represented on the vertical axis, which is plotted against the age in weeks on the horizontal axis. Dr Brazelton found that the crying times over weeks of the infants which he studied all turned out to follow a typical crying curve shape, which has since been confirmed to be the same for all population groups studied: Infants show a steady increase of crying time from birth up to 6 weeks, followed by a decrease to a steady level by 16 to 26 weeks. The general shape of the curve is the same for normal crying and colicky crying, it is the rate and degree of increase in crying times that distinguishes the two. The rate at which the crying is changing from week to week is represented by the slope of the curve, while the maximum duration of crying is the maximum height of the curve above the baseline. Colicky infants show a steeper curve, and a higher peak than their less voluble peers.

Figure 1 demonstrates the following points about infant crying: At birth, crying varies widely between individual normal infants, from 30 to 120 minutes per day. At this age, no crying and persistent inconsolable crying should be considered abnormal. After birth, babies who turn out to be be colicky infants rapidly increase their daily crying, usually reaching levels considered typical of colic by two weeks of age or earlier. This is the course of the purple line in figure 1, and the early onset can be seen as well in the start of the horizontal bars in figure 3. Fortunately for parents, most babies do not cry that much at two weeks (figure 1, the bottom three lines), nor would they ever reach this level, as is the case with the bottom two lines.

By four weeks of age crying has increased considerably above what it was at birth, and is usually still increasing. The upper two lines show that the baby who was diagnosed at 2 weeks of age as a case of infant colic has increased his daily crying even further, while a small number of infants who had previously not cried quite so disconsolately have reached a crying time of three hours per day. The latter pattern is represented by the red line in figure 1 crossing the yellow "180 minutes" line just before five weeks of age, and by the horizontal bars that start later than two weeks in the last cases illustrated in figure 3.

Reading from figure 1, at six weeks an average baby (green) would be crying for two and a quarter hours, a quiet baby (blue) for slightly more than an hour, and a colicky baby (red, and puple) from three hours to seven or more (the scale does not allow the last figure to be shown). After six weeks, crying starts decreasing to attain more or less steady levels - slightly more than an hour - at three to four months, usually maintaining this level of crying into the second year of life. Four out of five cases of colic would have resolved by six months. If excessive crying persists for longer than this, in a baby who has been considered to be suffering from infant colic, a reassessment of the diagnosis is in order.

There are some matters which the reader should be aware of when interpreting figure 1:

- These curves must not be used in the way infant growth charts are, as indicators of whether an individual infant is developing normally. As an example, a normal baby's head circumference does not increase and decrease by a few centimeters from day to day, but shows a smooth and steady increase over time, so that normal babies have head circumference measurements which are predictable by sex, age, race and population feeding status.[10][11] An increase in head circumference which does not follow the normal curve, is an indication that a condition such as hydrocephalus needs to be looked for and treated, if necessary, before the baby's brain suffers damage. Crying times have no such predictability, and no such diagnostic value. They vary enormously between babies, and in an individual baby from day to day. A crying time cannot be placed on one of the curves shown in the graph, and that used to work out expected crying times for the next few days or weeks.

- When the ups and downs of data for individuals are added together and averaged, they tend to cancel each other out, so that a graph depicting averages appears smoothed, and would not show what happens in an individual case. The points in figure 1 are derived from various sources, representing averages of groups of babies. For example, "average baby" (green) values at 2, 6 and 12 weeks are approximately the same as reported in 1962 [9], whereas values for colicky infants at six weeks come from a year 2000 congress poster.[12] The graph illustrates the trends in infant crying over time, not the irregular ups and downs of crying in an individual baby, by days or weeks. For an individual baby, a caregiver should therefore not be surprised or alarmed if periods of protracted colicky crying are interspersed with varying periods of normal crying;[13] by the nature of the data, this would not be seen in the figure. As a corollary: In a baby who has been crying excessively, it would be tempting to interpret a few days or a week of normal crying as the end of colic, and health care workers would like to be able to give such assurances, but it is only in retrospect that this can be known for sure; the graph cannot help to confirm or reject such an idea.

- A curve can be constructed from actual recorded serial measurements in an individual infant. This may have value when evaluated later on in the child's life, maybe more so if researchers were able to show that certain kinds of infant crying curves are associated with the later development of treatable or preventable disorders (such correlations have not yet been found). Furthermore, the dimensions that an individual curve will take on can not be extrapolated from initial measurements, the course and outcome of crying difficulties are not predictable by reference to published graphs, and crying curves are purely descriptive of a single infant or a specified group of infants.

Infant colic is not a recent problem. Hiscock and Jordan quote a description from the sixteenth century "The boke of chyldren", of problems crying related to "noyse and romblying in the guttes".[14] A working definition, the "Wessel criteria", formulated as long ago as 1954, defines infant colic as crying lasting more than three hours a day, on more than three days a week, for more than three weeks, in an otherwise well baby.[1] Originally crying and "fussiness" were described together, as symptoms which appear and disappear without reason or long-term meaning, but more recent workers consider that the two are not the same; crying is transient both in its manifestations and implications, while fussiness seems to be a more stable personality trait.[15]

The cardinal sign of infant colic is persistent inconsolable crying. This usually starts before two weeks of age. The crying occurs in bouts or paroxysms, most frequently in the evening (almost half occurs between six o'clock in the evening and midnight). During the attack the baby's face is contorted in apparent pain. Occasionally the eyes may remain open, and the child appear alert, in contrast to situations of pain and distress such as diaper dermatitis (nappy rash) with severe skin irritation, or the child who is very hungry - this is virtually diagnostic of colic, but not commonly noticed. The legs are drawn up and the whole body is rigid – neck, back, abdomen, and limbs. The attacks are frequently associated with the passing of flatus.[16]. Not everyone agrees that the clinical signs that are here described are necessary for the diagnosis, and in most cases they do not help to distinguish colicky crying from other problems.

The incidence of infant colic is uncertain, with quoted figures varying from 5% to 25% of infants at six weeks after birth. Definitions may differ in subtle ways, changing the incidence significantly. As an example, using Wessels criteria, but rephrasing the “more than three” (>3) to “at least three” (≥3), admits fourfold the number of babies to the diagnosis. Furthermore, studies may take into account the effect on parents, classifying infant colic by the parents’ perception of consolability, their opinions about the child being colicky, or of them being distressed by the crying. Thus, when applying ten different published definitions of infant colic, an incidence varying from 2% to 18% for the same group of babies was found.[17] Figures of between 15% and 20% are commonly quoted.

The cry of a colicky baby does not have any specific sound qualities which allows differentiation from more serious causes of prolonged inconsolable crying. It tends to be high-pitched, which caregivers associate with increased levels of distress in the infant, but what the cause or implication of the cry is cannot be inferred from that alone, since this high-pitched cry occurs in all babies who are irritated, stressed and physiologically aroused.[18] The interpretation of the cry depends on the listener, not on the crier.[19] The mother or caregiver has to decide whether the crying bout that she is faced with is "normal" for the baby, or is sufficiently different to cause her to seek the help of a health professional. Unfortunately, for these high-pitched, loud, persistent cries there are no rules or sets of rules, apart from the "red flags" described below, which will simplify the mother's decision; it is the deviation of the crying from her experience of the normal activity of the child which determines her actions. It is clear the the degree to which the crying bothers the mother plays a part in determining when a baby would be diagnosed as having colic, if at all.[20] It may be that the strong statistical correlations between, on the one hand, the factors of maternal psychological difficulties in pregnancy, family discord, maternal age and socio-economic status, and, on the other hand, the complaint of a colicky baby, are related by the mother’s interpretation of a cry that cannot be interpreted, rather than by any effect of these factors on the infant.[21] The same may be true for the father, which has important implications for the prevention of infant abuse.[22] See Addendum on Red flags.

Postulated causes and associated conditions

Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Vol 14, page 424, Copyright 1954 by the AAP.

There are a number of popular ideas in health science for what causes infant colic, which can be broadly divided falling into one of two general classes: as either "gut-theory" or as "developmental-psychosocial theory". It is frequently claimed that "the real problem" is one (or more) of the conditions of: gastroesophageal reflux, food allergy, lactose intolerance, bowel spasm or gas, or maternal and family psychosocial disturbances. Other experts claim that "there is no real problem", that the baby is normal and the excessive crying represents the upper range of normal development up to twelve weeks of age. In babies who have proven conditions that cause pain, there are elevated levels of the adrenal hormones that are released with stress. The absence of this elevated cortisol in babies with severe colic would indicate that there is indeed no pain, only crying; which would favour the normal development theory.[23]

Reproduced with permission from Pediatrics, Vol 14, page 427, Copyright 1954 by the AAP.

Normal crying starts at birth, and increases to an average of about 140 minutes per day by six weeks of age – this “age” being taken as if the baby had been born at full term, and frequently referred to as "gestational age", meaning the time lapsed since the baby was conceived. Thus, for an infant born two weeks prematurely, this "six weeks" is in reality eight weeks after the birth. Crying in babies has a definite diurnal rhythm, tending to occur more frequently in the evening (see figure 2: The crying hours). The posturing associated with crying spells, such as the facial changes, pulling up of legs and passing of wind that was described above for colic, is reported by many mothers who have no complaints about their child being colicky, or an excessive crier. The body signs are therefore unlikely to be specific to colic. Normally, crying decreases significantly by sixteen weeks of age. If it does not abate, but persists beyond six months of age, then an assessment for an underlying undiagnosed disease should undertaken.[24] This bears repetition: the pattern of an increase in crying from birth to six weeks, and then a rapid decrease to a steady level by sixteen to twenty weeks, is a normal pattern and occurs in all human societies that have been studied. It is not a reflection of poor or indifferent baby care; it is an expression of the normal development of the baby. It definitely does not mean that the parents are abusing or mistreating the baby. Much of what is called "colic" may actually be a normal event, interpreted by the parents in a negative way – a reflection of their own psycho-dynamics. Stated another way, the baby does not have a complaint, he is simply crying; the parent has the complaint.[25]

While the diagnosis of infant colic implies that there is no known underlying organic disease causing the crying, the diagnosis can quite easily be wrong. It is possible that a baby of the age that infant colic occurs may be crying for a reason that has remained unidentified. Statistically, no more than 5% of babies have an actual illness or correctable disturbance causing the crying. Even in those cases, the condition does not always require treatment for resolution, but gets better on its own. The rest of this section is applicable to this small proportion of colicky infants.

Acute illnesses (for instance infections or injuries) frequently have crying as a major symptom, which is one of the reasons why prolonged inconsolable crying should be assessed by a health worker, rather than having the caregivers manage the episodes of excessive crying as colic, until more symptoms appear. It is highly recommended that caregivers seek a professional opinion early on in the course of excessive crying - this is the wise course of action, not hypochondiasis by proxy. Persistent diarrhoea, rashes, vomiting and failure to gain weight argue even more strongly for a proper assessment of the baby.[26] It is equally wise to remember that when the health worker has not identified a definite cause for the crying, this does not exclude more serious problems with anything like 100% certainty, and conversely, where a separate disease has been diagnosed, its treatment will not necessarily solve co-incidental colic.

Lack of sleep and hunger are treatable causes of crying. The former may be due to excessive stimulation of the baby while awake, and this may be a factor in the finding that a reduction in stimulation seems to improve the complaints. Insufficient feeding requires advice and practical help to the caregivers about ways of increasing and monitoring the baby’s milk intake.

Food allergies may be a cause for excessive crying in both bottle-fed and breastfed babies. Mother's milk, cow’s milk and soy milk could be responsible, since they all contain allergens - in the case of breast milk, these may derive from the mother's diet. Changing the mother’s diet, or changing the bottle formula may be beneficial, but specific testing is usually not justified. In some cases a trial of a hypoallergenic formula yields benefits. This cannot be predicted before the change, and the reason for the benefit is usually not known.[27][28] A confounding factor is that colic resolves by itself, so that a benefit from the change in diet may coincide with a normal resolution of the excessive crying, leading to a false impression of efficacy. To illustrate this error, consider a baby who is experiencing a ten week long episode of colic, at the end of which the excessive crying disappears by itself (as it always does). If the parent or doctor had been trying out some new treatment every week for seven days before changing to another, then the treatment tried during the last one of the ten weeks will be found to be "the one that definitely works".

Lactose intolerance is an enzyme deficiency, not a food allergy. A temporary form frequently follows an infection such as gastroenteritis in a baby. It causes flatulence and diarrhoea that results from undigested lactose reaching the large bowel, where bacteria break it down to lactic acid and hydrogen. The faeces becomes acidic and irritating to the skin, causing a painful and sometimes infected nappy rash. The painful rash causes crying, and this sometimes stops when the irritating nappy is removed, suggesting the diagnosis. Lactose is present in both breast milk and in infant formula, so that a baby who has such a problem needs special feeding, lactase enzyme added to milk, or enzyme preparations given by mouth separately from the milk.[29][30] Lactose intolerance is usually transient, frequently following a bout of gastroenteritis.

Regurgitation of stomach contents into the esophagus and throat (gastroesophageal reflux) has been touted as a cause for infant colic, but it has been shown that while severe reflux can cause crying, the usual excessive crying is rarely caused by reflux. If reflux requires treatment then the treatment is for the reflux as such, not for colic; routine anti-reflux treatment does not reduce irritability and crying.

Excess swallowed gas can cause discomfort, but is rarely a cause for colicky behaviour. Unfortunately substances which reduce surface tension and facilitate burping (for instance simethicone) do not seem to make much difference to excessive crying.[31] On the other hand, the physical contact and soothing that goes along with attempts at getting rid of winds may calm the baby, so that successful treatment of many episodes of crying is not unexpected.

Statistically, the best predictors of complaints of infant colic is the age, parity and socioeconomic status of the mother.[21] This is a somewhat controversial issue, since many parents would take offence at the suggestion that the baby’s crying is the mother’s fault, and the reason for the correlation has not been defined. While there is no doubt that cases of ill treatment can lead to excessive crying, this is fortunately not the normal state of affairs. What is usually the issue is the parents’ ability to cope with the normal crying which they did not cause, rather than them causing abnormal crying.[32] It is the parents’ perception of the meaning of the persistent crying that leads to the doctor’s consultation. This seeking of a medical opinion in the face of uncertainty about her child's well-being is the correct action for a mother, but carries the risk that the crying becomes pathologised – that is, a normal event falsely diagnosed as a disease. The correct treatment in such cases would be reassurance, education and personal and social support for the parents while the baby carries on with his or her normal development.[25] Counseling the parents has been shown to give better results than eliminating cows milk protein and replacing it with a soy product, but the single study comparing the two approaches may have had design flaws, and further studies are needed.[33]

In a list of conditions that may be responsible for the 5% of cases of excessive crying which are due to underlying problems (and therefore not infant colic), the following diseases would be included: corneal abrasion, meningitis (bacterial and aseptic), otitis media, pneumonia, bronchiolitis, gastroesophageal reflux, strangulated hernia, torsion of the testis or appendix of the testis, urinary tract infection (especially pyelonephritis), intussusception, hair wrapped around the toes or fingers (hair strangulation or tourniquet), and systemic sepsis. These all need professional attention. The mother who is worried about her baby’s crying should never feel inadequate if she seeks professional help in working out why the excessive crying has arisen; there is a reasonable chance that there is a condition that deserves treatment. Colic cannot be diagnosed just on the history of the crying, such as by a telephonic consultation; when a health worker is consulted about this problem, then a physical examination should be done, with a follow-up examination if uncertainty remains. See Addendum on Red flags.

Management of the difficulties

Treat co-incidental disorders

If poor sleep or hunger contribute to the complaint, then parent training and support is usually required. Simple methods such as swaddling and avoiding over-stimulation can improve the quality of sleep,[34] while the cause for inadequate feeding should be determined and corrected. If treating these factors relieves the crying, the diagnosis of colic was incorrect.

Clearly a medical illness that causes excessive crying should be treated; specific disease need to be treated specifically. An infected nappy rash (impetigo) may require the use of anti-infective agents with subsequent preventative measures being instituted. Gastroesophageal reflux would dictate special feeding and positioning, as well as antacid therapy. Lactose intolerance may require feeding of special formulas or enzymes. When one considers that the increase and decrease in crying during the first six months of life is part and parcel of normal human development, and that there is a large normal variation in the duration of colicky inconsolable crying during this time, then it is clear that successful treatment of these irritating conditions would not necessary resolve the crying problem. There will be babies where the finding of a treatable illness is a coincidence, and not the reason for the colic. These cases would follow the course of normal colic, where it disappears by four months, in the course of normal development. Furthermore, a condition like gastroesophageal reflux may require continued treatment irrespective of whether the colic has disappeared.

Feeding change

Adequate feeding is essential. In this regard the technique of allowing the baby to empty a breast before changing to the other breast ensures that a sufficient amount of fats (more abundant in aftermilk) is taken in. This does seem to reduce the frequency of feeds and of hunger crying.[35] Overfeeding, speedfeeding (a South African community nurses' neologism meaning "not allowing rests and pauses during a feed, especially when a bottle is being used"), and failure to burp the baby can cause an increase in crying which may be avoided by a more gentle and relaxed technique. While this crying on its own would not be called colic, any reduction in the total time of crying is a relief to the caregiver.

Allergies to milk can be considered if the baby presents with chronic diarrhoea, vomiting, and failure to gain weight. The parent may know of confirmed cases in the family, and there may be other conditions such as atopic dermatitis and eczema. Onset before four weeks of age would tend to favour colic as a diagnosis, while allergies causing excessive crying frequently become symptomatic after that time.[26] As mentioned before, breastfeeding does not protect against lactose intolerance, and the same is true of cows milk allergy. If the mother takes in quantities of dairy products, the allergens are excreted in breast milk, and the baby ingests cows protein by proxy, as it were. This situation may require that the mother stop eating all dairy products. This is inconvenient, difficult to stick to, and may turn out to be quite expensive. It may be more practical to try an infant feed which contains soy or hydrolysed proteins, or esoteric milks such as goats milk, depending on geographical and financial considerations. A low allergen diet in the mother of the colicky child may reduce symptoms.[36]

Lactose intolerance is considered a transient condition in the majority of cases, with most of these babies probably never even being diagnosed, since their symptoms do not warrant testing or disappear spontaneously (for instance, symptoms of gastroenteritis lasting slightly longer than expected, but not causing significant morbidity). As far as lactose intolerance is concerned, the lay public rarely considers that a baby could be reacting unfavourably to his own mother’s breast milk.

Conventional Medications

Gastrointestinal spasm has not been clearly established as a major cause for infant colic, despite the name for the condition. There are two drugs which have been shown to be consistently effective at combating spasm, but again, there is no reason to even consider their use unless the specific diagnosis of gastrointesinal spasm is suspected. Both these drugs act on the smooth muscle of the gut, to cause relaxation. The older drug, dicyclomine, is particularly effective, but has been associated with serious side effects like breathing problems, weakness and depressed consciousness in babies, so that it is contraindicated in infants under 6 months old. Because it is excreted in breast milk, nursing mothers must not use this medication either.[37] Cimetropium is another anti-cholinergic drug which has been shown to reduce the excessive crying,[38] and does not seem to carry the same risks as dicyclomine. If the developing idea that much of what is pathologised as infant colic is in fact normal development, then simply reducing the tone of the gut on its own would not be predicted to resolve the difficulty of excessive crying. Since both these medications cause sedation and sleepiness, it is possible that the beneficial effect is on the central nervous system. This raises the question of whether it would be wise to use such treatments indiscriminately. Infant neurons in the central nervous system are undergoing myelination and the making of synaptic connections at the age that infant colic spans in the life of an affected child. Anti-cholinergic drugs can theoretically alter the subtle nuances of brain development, and so their use cannot be taken lightly.

Windiness (gas)– both burping and anal flatulence – is a common accompaniment to the symphony of colic. Therefore oral simethicone, a surface tension reducing agent which breaks up bubble formation, has been tried in an effort to help the baby “get rid of the winds”. Trials have shown no therapeutic benefit over placebo, which is what would be expected if the windiness were not the primary problem.

The use of oral lactobacillus in feeds shows promise, but at present one should be no more than cautiously optimistic about the applicability of the treatment to colicky babies in general. In a single trial of babies with the diagnosis of colic, responders to lactobacillus treatment exceeded responders to simethicone treatment by an order of magnitude.[39] If the investigators' protocols and analyses were valid, such dramatic results should not be difficult to duplicate, with eventual benefit to many suffering families.

Alternative medications

Plant preparations which have been shown to help for colic include herbal teas[40] and fennel oil emulsion,[41] both of which were effective in double blind trials. The tea described consisted of a mixture of chamomile (Matricaria chamomilla), vervain (Verbena officinalis), licorice (Glyhrizza glabra), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare), and lemon balm (Melissa officinalis). The dosage for the fennel oil was reported as 5 to 20 ml of an 0.1% emulsion in water, up to four times per day. These treatments are not entirely harmless, and proper doses have not been scientifically determined. Indeed, if they do work, then it means that they possess potentially powerful gastrointestinal or nervous system actions of unknown nature. A concern is that the volume of tea given may reduce the intake of food (the total volume of fluid given per day works out to be about the same as a single feed), while the chemicals found in fennel oil may cause nervous system side-effects such as convulsions. Once the reason for their efficacy is determined, along with a safety profile of doses and side-effects at various doses, these herbals would become part of the armamentarium of scientific medicine.

Physical, behavioral and emotional therapies

There are no known physical treatments which reliably eliminate excessive crying in a baby with infant colic. The general recommendation is that any physical discomfort of the infant - conditions such as hunger, cold, an irritating rash, or a wet nappy - should be attended to , and that physical techniques such as touch, carrying, and soothing sound should all be employed to settle the agitated nervous system. This may reduce crying by half, but does not eliminate colic.

The oft-quoted studies of the !Kung San in Southern Africa showed that in a culture where babies are carried all day and fed on demand, infant colic is not a problem, even though the crying graph for the first year of life follows the same pattern of peaking at six weeks and stabilising at four months as it does for infants in Western countries.[42] Efforts to reproduce those circumstances and results in infants with colic have met with little success.[43]

Canadian pediatrician Ronald Barr has developed a new approach to the problem, basing it on the likelihood that colic is simply one extreme of normal, and that the problem lies rather with the response that uninterrupted crying evokes in caregivers. As part of an effort to reduce parental frustration and impulsive acts towards the baby, he has coined the acronym PURPLE crying, for the characteristics of this normal stage of human development. The intent is to educate and help caregivers remember that the colicky activity is neither selfish, nor maliciously intended, nor a sign of disease, nor easily dampened by even the best of care, thereby possibly reducing the incidence of the shaken baby syndrome. This challenges the idea that the crying indicates that “something is wrong” for which which “something must be done”. An appropriate response would be prompt, appropriate and caring; the idea that leaving a baby to cry has an educational or training value is unscientific and without any merit at all - to think that babies of three months old can be spoilt is equally wrong. Such an appropriate response includes touching, carrying, rocking, singing, talking to, swaddling and tucking to settle the baby. It emphasises the wisdom of leaving the infant in a safe situation when the crying becomes intolerable for the caregiver, rather than losing control of impulses. It is important for the caregiver to realize that the baby's continued crying is "just one of those things that some babies do at this age" rather than a rejection of the caregiver or a sign of an implacable nature in the baby.

| P = Peaks at around two months of age. |

| U = Unpredictable, often happening for no apparent reason. |

| R = Resistant to soothing. |

| P = Pain-like expression on the baby's face, even without any source of pain. |

| L = Long bouts, lasting 30 to 40 minutes or more. |

| E = Evening crying. |

A multimodal intervention that teaches similar techniques has been tried in Australia, with promising results. It employed multiple strategies in mothers and children who were admitted to a care center. The teaching of techniques of settling the baby, as well as maternal education, practical help and counselling lead to a significant decrease in problems with colic, both during the stay and on follow-up a month after discharge.[45] In keeping with the evolving concept of colic being at least as much of a problem for the caregivers as it may be for the baby, attention is increasingly being given to educating and supporting the mother and family. Increased sensitivity to, early treatment of, and extended support for parents with coping difficulties, depression and anxiety states after the baby's birth is advocated.[26]

Consequences

Infant colic has no known long-term physical consequences for the baby. To prevent short-term consequences, the first priority is to find and treat other potentially harmful disorders which may look (or sound!) the same. The second is to manage the extreme frustration and emotional distress which the inconsolable crying of a child can cause in the parent. The incidence of the shaken baby syndrome follows that of the normal increase and reduction of crying accurately, although it shows a lag of about a month. The lag may be explained by the fact that the abuse statistic is generated at the time that the condition is diagnosed, not the time of first injury.[25] Persons outside of the family need to be aware of the stress which the excessively crying baby can place on a family, and suitable steps taken enabling parents to cope.

It appears that excessive infant crying can have consequences for long-term psychological well-being, presumably based on the disturbed mother-baby relationship which develops. Conversely, the irritability of some colicky babies may simply be the early signs of the later difficulties. These irritable babies have an increased disposition to behavioural and sleep difficulties as preschool toddlers, but this has not been followed through to adult age.[46]

Conclusion

Infant colic is not an inconsequential disorder, it may have disastrous effects on the baby and the family. While the gut theory of colic remains accepted as viable, and supported by treatments and research aimed at relieving gastro-intestinal problems, the opinion that infant colic is also a normal human developmental stage has gained ground.[47] Education about how to cope with the situation and utilise extended family help as well as social services, combined with a trial of dietary modification, may be better treatment than initially trying medications for the baby. Such an approach seems to be far better than brushing off the complaint of infant colic as unimportant, and is supported by an extensive literature on the subject, both popular and professional.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 Wessel MA, Cobb JC, Jackson EB,. Harris GS Jr., Detwiler AC. Paroxysmal Fussing in Infancy, Sometimes Called "Colic". Pediatrics Vol. 14 No. 5 November 1954, pp. 421-435. PMID 13214956

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Levitzky S, Cooper R. Infant Colic Syndrome - Maternal Fantasies of Aggression and Infanticide. Clin Pediatr. 2000;39:395-400. PMID 10914303

- ↑ St James-Roberts I. Persistent infant crying. Arch Dis Child. 1991;66:653–655. PMID 2039262

- ↑ Forsyth BWC, Canny PF. Perceptions of vulnerability 3 1/2 years after problems of feeding and crying behavior in early infancy. Pediatrics 1991; 88:757-763. PMID 1896279

- ↑ Rogovik AL, Goldman RD, Treating infants’ colic. Can Fam Physician. 2005 September 10; 51(9): 1209–1211. PMID 16190173

- ↑ Krugman RD. Fatal child abuse: analysis of 24 cases. Pediatrician. 1983-1985;12(1):68-72. PMID 6571113

- ↑ Friedman SH, Horwitz SM, Resnick PJ. Child Murder by Mothers: A Critical Analysis of the Current State of Knowledge and a Research Agenda Am J Psychiatry 2005 Sep;162(9):1578-87. PMID 16135615

- ↑ Soltis J. The signal functions of early infant crying. Behav Brain Sci. 2004 Aug;27(4):443-58; discussion 459-90. PMID 15773426

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Brazelton TB. Crying in infancy. Pediatrics 1962:29:579-588. PMID 13872677

- ↑ Eregie CO. Exclusive Breastfeeding and Infant Growth Studies: Reference Standards for Head Circumference, Length and Mid-arm Circumference/Head Circumference Ratio for the First 6 Months of Life. Journal of Tropical Pediatrics 2001 47(6):329-334. PMID 11827299

- ↑ Examples of head circumference charts can be found at the website of the US National Centre for Health Statistics, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Clinical Growth Charts page.

- ↑ Barr RG, Paterson J, MacMartin L, Calinoiu N, Young SN. The infant reactivity inventory (IRI) in infants with and without colic: replication and validation. Poster group: Infant crying. 12TH Biennial International Conference on Infant Studies, Brighton 2000. Monday, July 17. Program available at http://www.isisweb.org/ICIS2000Program/web_pages/programMonday.html. Accessed 20070413.

- ↑ St James-Roberts I, Plewis I. Individual Differences, Daily Fluctuations, and Developmental Changes in Amounts of Infant Waking, Fussing, Crying, Feeding, and Sleeping. Child Development 1996 Oct;67(5):2527-2540. PMID 9022254

- ↑ Phaer Thomas. The boke of chyldren (1544) (edited with an introduction, notes and glossary by Rick Bowers. Tempe, Ariz: Center for Medieval and Renaissance Studies, 1999. (Medieval and Renaissance Texts and Studies, vol 201.). Quoted in: Hiscock H, Jordan B. Problem crying in infancy. MJA 2004; 181 (9): 507-512 PMID 15516199

- ↑ St James-Roberts I, Plewis I. Individual Differences, Daily Fluctuations, and Developmental Changes in Amounts of Infant Waking, Fussing, Crying, Feeding, and Sleeping. Child Dev. 1996 Oct;67(5):2527-40. PMID 9022254

- ↑ Illingworth RS. "Three months" colic. Arch Dis Child. 1954 Jun;29(145):165-74. PMID 13159358

- ↑ Reijneveld SA, Brugman E, Hirasing RA. Excessive Infant Crying: The Impact of Varying Definitions. Pediatrics. 2001 Oct;108(4):893-7. PMID 11581441

- ↑ Fuller BF, Keefe R, Curtin M. Acoustic Analysis of Cries from "Normal" and "Irritable" Infants. Western Journal of Nursing Research 1994;16(3):243-253. PMID 8036801

- ↑ Zeskind PS. Impact of the cry of the infant at risk on psychosocial development. In: Tremblay RE, Barr RG, Peters RDeV, eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development; 2005:1-7. Available at: http://www.excellence-earlychildhood.ca/documents/ZeskindANGxp.pdf. Accessed 20070402.

- ↑ van der Wal MF, van den Boom DC, Pauw-Plomp H, de Jonge GA. Mothers' reports of infant crying and soothing in a multicultural population Arch Dis Child 1998 October;79:312-317. PMID 9875040

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Crowcroft NS, Strachan DP. The social origins of infant colic: questionnaire study covering 76,747 infants. BMJ 1997 May 3;314(7090):1325-8. PMID 9158470

- ↑ Carbaugh SF. Understanding Shaken Baby Syndrome. Adv Neonatal Care 2004 Apr;4(2):105-14; quiz 15-7. PMID 15138993

- ↑ White BP, Gunnar MR, Larson MC, Donzella B, Barr RG. Behavioral and physiological responsivity, sleep, and patterns of daily cortisol production in infants with and without colic. Child Dev. 2000 Jul-Aug;71(4):862-77. PMID 11016553

- ↑ St James-Roberts I, Halil T. Infant crying patterns in the first year: normal community and clinical findings. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1991 Sep;32(6):951-68. PMID 1744198

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 Barr RG. Crying behaviour and its importance for psychosocial development in children. In: Tremblay RE, Barr RG, Peters RDeV, eds. Encyclopedia on Early Childhood Development [online]. Montreal, Quebec: Centre of Excellence for Early Childhood Development; 2006:1-10. Available at: http://www.excellence-earlychildhood.ca/documents/BarrANGxp.pdf. Accessed 20070321

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Hiscock H, Jordan B. Problem crying in infancy. MJA 2004; 181 (9): 507-512. PMID 15516199

- ↑ Lucassen PLBJ, Assendelft WJJ, Gubbels JW, van Eijk JTM, van Geldrop WJ, Knuistingh Neven A. Effectiveness of treatments for infant colic: systematic review. BMJ. 1998 May 23;316(7144):1563-1569. PMID 9596593

- ↑ Hill DJ, Hudson IL, Sheffield LJ, Shelton MJ, Menahem S, Hosking CS. A low allergen diet is a significant intervention in infant colic: results of a community-based study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 1995 Dec;96(6 Pt 1):886-92. PMID 8543745

- ↑ Kanabar D, Randhawa M, Clayton P. Improvement of symptoms in infant colic following reduction of lactose load with lactase. J Hum Nutr Diet. 2001;14(5):359–363 Abstract

- ↑ Lucassen, PL.;Assendelft, WJ.;Gubbels, JW.;van Eijk, JT.; Douwes, AC. Infant colic: crying time reduction with a whey hydrolysate: a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. Pediatrics. 2000;106:1349–1354 Abstract

- ↑ Metcalf, TJ.;Irons, TG.;Sher, LD.; Young, PC. Simethicone in the treatment of infant colic: a randomized, placebo-controlled, multicenter trial. Pediatrics. 1994 Jul;94(1):29-34. PMID 8008533

- ↑ Barr RG. Colic and Crying Syndromes in Infants. Pediatrics. 1998 Nov;102(5 Suppl E):1282-6. PMID 9794970

- ↑ Taubman B. Parental counseling compared with elimination of cow's milk or soy milk protein for the treatment of infant colic syndrome: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 1988 Jun;81(6):756-61. PMID 3285312

- ↑ Gerard CM, Harris KA, Thach BT. Spontaneous Arousals in Supine Infants While Swaddled and Unswaddled During Rapid Eye Movement and Quiet Sleep. Pediatrics. 2002 Dec;110(6):e70. PMID 12456937

- ↑ Evans K, Evans R, K Simmer K. Effect of the Method of Breast Feeding on Breast Engorgement, Mastitis and Infant Colic. Acta Paediatr. 1995 Aug;84(8):849-52. PMID 7488804

- ↑ Garrison MM, Christakis DA. A Systematic Review of Treatments for Infant Colic. Pediatrics. 2000 Jul;106(1 Pt 2):184-90. PMID 10888690

- ↑ Barr RG. Changing our understanding of infant colic. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2002;156(12):1172–4. PMID 12444822

- ↑ Savino F, Brondello C, Cresi F, Oggero R, Silvestro L. Cimetropium bromide in the treatment of crisis in infant colic. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2002 Apr;34(4):417-9. PMID 11930101

- ↑ Savino F, Pelle E, Palumeri E, Oggero R, Miniero R. Lactobacillus reuteri (American Type Culture Collection Strain 55730) versus simethicone in the treatment of infant colic: a prospective randomized study. Pediatrics. 2007 Jan;119(1):e124-30. Download pdf

- ↑ Weizman Z, Alkrinawi S, Goldfarb D, Bitran C Efficacy of herbal tea preparation in infant colic. J Pediatr. 1993 Apr;122(4):650-2. PMID 8463920

- ↑ Alexandrovich I, Rakovitskaya O, Kolmo E, Sidorova T, Shushunov S. The effect of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare) seed oil emulsion in infant colic: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. Altern Ther Health Med. 2003 Jul-Aug;9(4):58-61. PMID 12868253

- ↑ Barr RG, Konner M, Bakeman R, Adamson L. Crying in !Kung San infants: a test of the cultural specificity hypothesis. Dev Med Child Neurol. 1991 Jul;33(7):601-10. PMID 1879624

- ↑ Pinyerd B. Strategies for consoling the infant with colic: fact or fiction. J Pediatr Nurs. 1992 Dec;7(6):403-11. PMID 1291676

- ↑ McIlroy, Anne. For Crying Out Loud. The Globe and Mail, Toronto, Canada. March 27, 2004. Reprinted on the website of the National Center on Shaken Baby Syndrome, http://www.dontshake.com/Subject.aspx?categoryID=13&PageName=ResearchOnCrying.htm Accessed 20070402.

- ↑ Don N, McMahon C, Rossiter C. Effectiveness of an individualized multidisciplinary programme for managing unsettled infants. J Paediatr Child Health. 2002 Dec;38(6):563-7. PMID 12410867

- ↑ Rautava P, Lehtonen L, Helenius H, Sillanpaa M. Infant colic: child and family three years later. Pediatrics. 1995 Jul;96(1 Pt 1):43-7. PMID 7596720

- ↑ Crotteau CA, Wright ST, Eglash A. Clinical inquiries. What is the best treatment for infants with colic?. Journal of Family Practice. 2006 Jul;55(7):634-6. PMID 16822454

Addendum: "Red flags" in excessive crying.

A red flag in medical parlance is a finding which is an indication that there may be a serious condition underlying the person's complaint, even if the complaint itself is apparently trivial. An example which most would be familiar with, through cancer education, is a pigmented nevus (mole on the skin) which develops an ulcer and starts bleeding. While a small bleeding wound on the skin is hardly dangerous, the event is a red flag warning that the part of the mole may have become cancerous, requiring treatment before it spreads. While Citizendium is not a manual of home health care or self-care, and this article is not about the causes of crying, we believe that it is in the interest of babies and caregivers that the most important red flags relating to excessive crying in infants be available to readers.

Since the baby can not speak for herself, and the fact of crying as such gives no indication if something is wrong somewhere, attempts have been made to discern the reason for crying by analysis of the nature of the cry itself. Unfortunately these been unsuccessful at differentiating colic from other causes of excessive crying - the volume, tone and duration of crying simply seems to indicate distress from any cause. Therefore doctors have identified red flags for the complaint, which would alert the clinician that the problem may be more severe than meets the eye. These relate to the medical history of the baby, both antenatal and after birth, as well as certain signs noted on examination. A caregiver would be expected to be familiar with the baby's medical history, but cannot be expected to evaluate clinical signs, so that the latter have less utility for the mother who has to decide whether to rush off to an emergency department with her baby. Red flags in the history include:

- Antenatal or obstetric problems, specifically drug use by the mother during pregnancy, prolonged rupture of the placental membranes, a mother who developed a fever or infection associated with the birth, and a baby who became jaundiced after birth.

- Poor feeding and failure to gain weight normally, or vomiting, especially a forceful expulsion of stomach content stained with bile or blood (so-called projectile vomiting). A bloody diarrhoea.

- Recently becoming lethargic, with fewer movements, has spells where she stops breathing or becomes a blue or purplish color, or seems to get convulsions or spasms of the body or limbs.

- Fever of greater than 38°C (100.4°F) in a baby less than 3 months old; a baby who feels cold and whose hands and feet stay blue; an irritable child who refuses to be held; rashes, eruptions, bumps, or discharges.

- Head injury, or a history of repeated injuries - bruise or fracture - to the torso and limbs, injuries that can't be explained by the history. We do not know for sure why some caregivers assault babies, but colic is one of the contributory factors, and keeping quiet about possible infant abuse may be fatal to the baby.

- Recent treatment with antibiotics for an infection anywhere.

- History does not fit in with colic, for instance baby more than 3 months old, no pattern of increased crying at night.

As far as the signs of disease go, the red flags that the doctor examining the infant would be looking for include the warning signs for all the diseases mentioned in the section on postulated causes. If the examiner is not satisfied with the diagnosis that she is able to make, then it would not be unusual for a second appointment to be scheduled, for the doctor to ask a colleague who is more comfortable with examining neonates for an opinion, or for her to arrange for the baby to be seen by a pediatrician.

The parents or caregivers can help in the diagnosis if they keep a record of all fussing or crying spells, as well as the baby's daily activities and routines (for instance nappy changes, diarrhoea, bringing up food). Unusual movements or routines should be noted, as these tend to be forgotten in the doctor's office, unless written down, an example being the infant with otitis media who touches his ear continually. They should be sure about the advice they were given about managing the baby, and clear about what signs of a change in the baby's condition to look out for at home.

The interested reader is referred to other free texts on the internet, which discuss the problem of crying from different perspectives.

- Boychuk RB. Infant Colic. University of Hawaii Case Based Pediatrics For Medical Students and Residents. University of Hawaii John A. Burns School of Medicine. April 2003. Available at http://www.hawaii.edu/medicine/pediatrics/pedtext/s09c01.html Accessed 20070315.

- D'Alessandro DM. What Should I Do? I Just Can't Get Him to Stop Crying? PediatricEducation.org. November 2005. Available at http://www.pediatriceducation.org/2005/11/07. Accessed 20070410.

- Woo-Ming MA. Colic. eMedicineHealth. August 2005. Available at http://www.emedicinehealth.com/colic/article_em.htm. Accessed 20070410.