Hippocrates: Difference between revisions

imported>Anthony.Sebastian |

imported>Anthony.Sebastian (→The emergence of Hippocratic medicine: add ref) |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

The Hippocratic philosophy of medicine mirrored the emerging philosophy of the natural causes of things and events in the world that began with the Ionian philosopher, Thales of Miletus (c. 625-546), whose scientific as opposed to mythological thinking gave birth to Western scientific thought. Hippocrates’ life overlapped that of the great Greek natural philosophers Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (429-347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Thus he lived during the Golden Age of Greece (c. 500 – 300 BCE). Disease, so central in human lives, not surprisingly would come under scientific scrutiny in the environment of such thinkers. Historians know that Hippocrates observed keenly ("''infinite in faculty''"), reasoned rationally ("''noble in reason''"), and taught and practiced a holistic ideal of medicine ("''what a piece of work is Man''")<ref> | The Hippocratic philosophy of medicine mirrored the emerging philosophy of the natural causes of things and events in the world that began with the Ionian philosopher, Thales of Miletus (c. 625-546), whose scientific as opposed to mythological thinking gave birth to Western scientific thought. Hippocrates’ life overlapped that of the great Greek natural philosophers Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (429-347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Thus he lived during the Golden Age of Greece (c. 500 – 300 BCE). Disease, so central in human lives, not surprisingly would come under scientific scrutiny in the environment of such thinkers. Historians know that Hippocrates observed keenly ("''infinite in faculty''"), reasoned rationally ("''noble in reason''"), and taught and practiced a holistic ideal of medicine ("''what a piece of work is Man''")<ref> | ||

*'''<u>Note:</u>''' | *Regarding parenthetical quotes: | ||

'''<u>Note:</u>''' From Shakespeare's "Hamlet", Act I. Scene II.</ref> | |||

<ref name=ventegodt>Ventegodt,S.; Kandel,I.; Merrick,J. (2007) [http://dx.doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2007.238 A short history of clinical holistic medicine.] ''ScientificWorldJournal 7:1622-1630.PMID 17982604 | <ref name=ventegodt>Ventegodt,S.; Kandel,I.; Merrick,J. (2007) [http://dx.doi.org/10.1100/tsw.2007.238 A short history of clinical holistic medicine.] ''ScientificWorldJournal 7:1622-1630.PMID 17982604 | ||

*'''<u>Abstract:</u>''' Clinical holistic medicine has its roots in the medicine and tradition of Hippocrates. Modern epidemiological research in quality of life, the emerging science of complementary and alternative medicine, the tradition of psychodynamic therapy, and the tradition of bodywork are merging into a new scientific way of treating patients. This approach seems able to help every second patient with physical, mental, existential or sexual health problem in 20 sessions over one year. The paper discusses the development of holistic medicine into scientific holistic medicine with discussion of future research efforts,</ref> that regarded health and disease as manifestations of body and mind as a whole. | *'''<u>Abstract:</u>''' Clinical holistic medicine has its roots in the medicine and tradition of Hippocrates. Modern epidemiological research in quality of life, the emerging science of complementary and alternative medicine, the tradition of psychodynamic therapy, and the tradition of bodywork are merging into a new scientific way of treating patients. This approach seems able to help every second patient with physical, mental, existential or sexual health problem in 20 sessions over one year. The paper discusses the development of holistic medicine into scientific holistic medicine with discussion of future research efforts,</ref> that regarded health and disease as manifestations of body and mind as a whole. | ||

Revision as of 13:32, 29 April 2008

Of all the men in ancient Greece who shared the name, Hippocrates — a common Greek name like ‘Edward’ or ‘Lawrence’ in English — many such who distinguished themselves in Greek history in one way or other, only one Hippocrates, Hippocrates of Cos (c. 460 – 370 BCE), a physician, reigned with honor and respect throughout Western history to the present day. The revolution in medicine that he began and inspired so changed the course of Western civilization that the health and welfare of all humanity has benefited.

Hippocrates of Cos revolutionized the practice of medicine by transforming it from its mythical, superstitious, supernatural roots to roots based on observation and reason — the roots themselves of scientific objectivity — roots that have grown an evolutionary tree of Western scientific medicine that ever continues to flourish. For that reason History has bestowed on Hippocrates of Cos the honorific cognomen, “The Father of Medicine”, medicine’s progenitor. We might call him more accurately "The Progenitor of Western Scientific Medicine".

In many accounts of Hippocrates of Cos, the writers bemoan a lack of information about his life and work. Truly many gaps exists. But recent scholarship of exemplary quality still allows us to say much about the historical Hippocrates of Cos, about his life, his work and reputation during his lifetime, his travels, and his legacy — with reasonable certainty and very high probability. [1]

Hippocrates’ life on the island of Cos

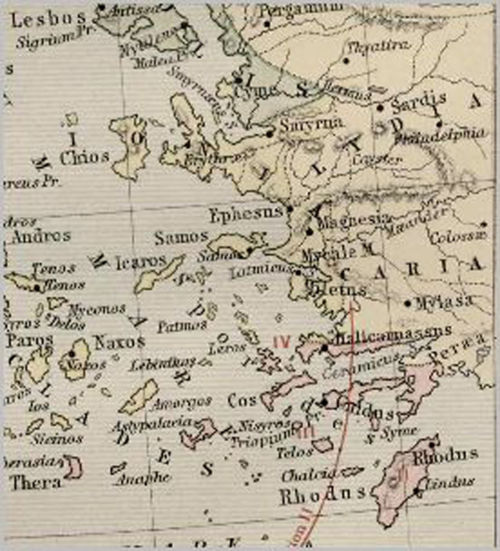

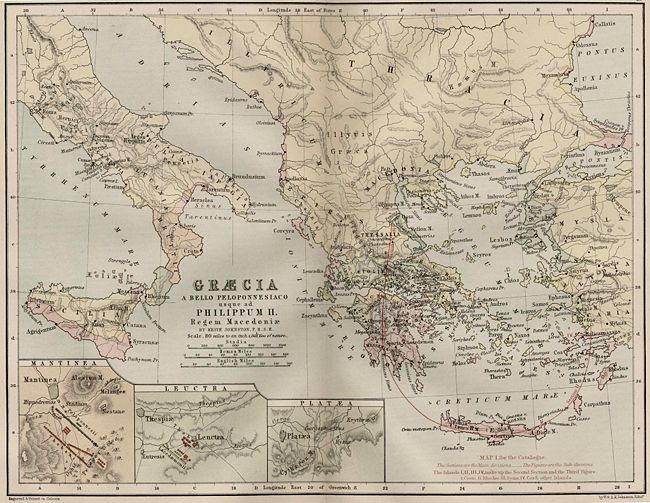

Hippocrates entered the world into an aristocratic family on the Ionian island of Cos (or Kos), located in the Aegean Sea off the southwest coast of Ionia (Asia Minor, present day Turkey).[2] His father, Heraclides, practiced medicine employing ancient ideas of supernatural causation and treatment of disease according to the tradition linked to the Greek mythical god of healing, Asclepius. In fact, Heraclides traced his ancestry back to Asclepius in the era of the Trojan war, when Asclepius, a physician, had not yet achieved godhood. Haraclides descended from Asclepius’s son, Podalirius, who fought in the Trojan war, moved to Asia Minor, and whose descendents eventually settled on Cos. The tradition of Asclepian medicine passed from son to son down the generations, eventually reaching Heraclides. The family from Podalirius onward called themselves Ascelpiads, their family name. At the time of Hippocrates’ birth, Cos paid tribute to Athens as a member of the Athenian federation created to defend against Persian aggression.

Hippocrates, though known also as 'Hippocrates of Cos, the Asclepiad', and though reared in the family tradition of Asclepian medicine, nevertheless rejected the supernatural ethos, sparking a revolution of principles and practice in medicine that present day non-supernatural Western scientific medicine acknowledges as its heritage. Scholars have found no evidence of Hippocrates ever practicing as a physician priest of Asclepius.

Hippocrates’ education within the family probably included in addition to medicine philosophy and rhetoric and other subjects that gave him knowledge of the world of reality. He remained on Cos well into maturity, married and had two sons and a daughter. His new practice of medicine according to observation and reason gained him fame in and beyond Cos. One plausible story has him rejecting an invitation to court of the current king of Persia. [3]

The emergence of Hippocratic medicine

The Hippocratic philosophy of medicine mirrored the emerging philosophy of the natural causes of things and events in the world that began with the Ionian philosopher, Thales of Miletus (c. 625-546), whose scientific as opposed to mythological thinking gave birth to Western scientific thought. Hippocrates’ life overlapped that of the great Greek natural philosophers Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), Socrates (469–399 BCE), Plato (429-347 BCE) and Aristotle (384-322 BCE). Thus he lived during the Golden Age of Greece (c. 500 – 300 BCE). Disease, so central in human lives, not surprisingly would come under scientific scrutiny in the environment of such thinkers. Historians know that Hippocrates observed keenly ("infinite in faculty"), reasoned rationally ("noble in reason"), and taught and practiced a holistic ideal of medicine ("what a piece of work is Man")[4] [5] that regarded health and disease as manifestations of body and mind as a whole.

Because historians know only smatterings of the life of Hippocrates, and because of the great influence he and his disciples have had on medicine for millennia, his fame as a physician has led to a plethora of writings about him that have the character of legend:

We still know very little about Hippocrates. And yet, like the physicians of Imperial Rome, the doctors of our days want to know all about the life of the "Father of Medicine." Where there are no historical sources available, imagination will step in, and the poet will replace the historian.[6]

Hippocrates founded a school of medicine known by his name, and advocated a basic approach to the diagnosis and treatment of disease that still has applications in modern medicine. [For example, see Pappas et al.[7] and Chang et al.[8]]

Why do modern day researchers keep going back to Hippocrates?....although ancient, some notions expressed in the Hippocratic works are still applicable today. What is more important though, is a reason easily recognized to anyone familiar with Hippocratic descriptions of infection: the clarity of presentation of the clinical course and the astute inclusion of infection in a broader environmental and social context are still unparalleled by modern thinking."[7]

History gave his name to an oath of medical ethics called the Hippocratic Oath. "The code of conduct for doctors outlined in the Hippocratic Oath, a vow commonly taken by modern doctors", remains an ethical guideline in medicine.[9] One can begin to appreciate the influence of Hippocrates to the present day by his presence in the World Wide Web since the year 2000, where the scientific search engine, SCIRUS, reveals 74,523 entries, and Google search reveals ~172,000 entries for the twelve months preceding April 2008.

Early Greek medicine operated as a supernatural, magical art. The god of healing, Asclepius (Aesculapius in Roman terminology), [10] whose priests and temples flourished in ancient Greece at least from the Homeric era, appeared in the dreams of the sick who came to the temple for 'sleep therapy'. Asclepius gave advice to the dreamer, which the priests interpreted. The priests prescribed baths, diets, exercises, changes in occupation or living locales, and other routines, and those prescriptions received credit when cures occurred. The cult of ‘therapeutic dreaming’ persisted in various places even into Christian times.

Hippocratic medicine developed as the "naturalistic counterpart" of the Asclepian supernaturalistic tradition.[11] By the 6th century BCE (the 500s BCE) Greek philosophers emerged and began to theorize about the natural causes of the way the world worked. Empedocles (ca. 495-435 BCE), characterized as a physician and philosopher, postulated earth, air, fire and water as the primordial elements of which everything in the world consisted, in differing combinations and kinds of combinations, including the human body.[12] [13]

The development of Hippocratic medicine, its [Aesculapian medicine’s] naturalistic counterpart, is considered a turning point in the history of the healing arts although, as we have seen, at about the same time, naturalistic medical paradigms were developing in other ancient civilizations as well. The importance of Hippocratic medicine rests on the fact that it is the first comprehensive naturalistic medical system of the Western world and therefore the source from which scientific medicine would eventually originate.[11]

Indeed, the development of Hippocratic medicine may have influenced changes in the persisting Asclepian practice.[14]

For its objectives of seeking classification, causes and remedies of disease, medicine requires reason, but not only reason. Considering that knowledge emerges from information processed by reason, not only does the quality of reason count, but also does the quality of the information fed into reason count. Reason will yield a formally valid conclusion, but if fed flawed information, it will not yield a reliable conclusion. For the latter, reason requires information ultimately based on empirically sound observation. If based on wishful thinking, imagination, unquestioned assumptions, believed revelation by deities, guesswork and the like, reason yields at best dubious knowledge and at worst false knowledge. Hippocrates appears to have understood that, and as a physician considered to epitomize the art of medicine, as Socrates did, he inspired many likeminded and knowledge-seeking followers.

Likely inspired by Empedocles’ concept of four elements making up natural things, the concept of four humours (blood, yellow bile, black bile, phlegm) as constituent elements of the human body emerged as part of the Hippocratic tradition, the individual humours in various combinations determining state of health and personality:

- excess blood makes a person ‘sanguine’, full of energy, optimistic, ruddy complected

- excess yellow bile makes a person ‘bilious’, ‘choleric’, bad tempered, quick to anger, irritable

- excess black bile makes a person ‘melancholic’, deeply and long-lastingly sad

- excess phlegm makes a person ‘phlegmatic’, unemotional, temperamentally slow, calm

Historians have not identified an individual who originated the four humours theory, nor have they excluded the possibility that the theory emerged into a formal theory only gradually. [15]

The medical corollary of Empedocles' theory is the identification of the traditional humours with constituent elements: what made this possible was the presence, in the traditional view of humours, of positive characteristics. Because of these characteristics it was easy to conceive the humours as the ingredients of man, upon which his normal or healthy state, as well as his very existence, depended….It is not the recognition of this or that humour as existing which counts, but the theoretical use to which that humour is put. One would therefore also have to find evidence….that the humours were regarded as constituent parts of the human body. There seems no a priori reason why this should not have been the case, in any writer working after say 450. But in the absence of such evidence, the question of the precise originator of the four-humoral theory is formally insoluble….What is perhaps of more interest is the way in which the theory of four humours exemplifies the stimulating effects of Greek philosophy on Greek medical science. It may be described in this way: the philosopher provides the categories within which the medical scientist can order his experience.” Page 61[15]

The Hippocratic documents

21st century scholarly interest in and diversity of views of Hippocrates

- Some Abstracts paragraphed for ease of reading

- Grammaticos PC, Diamantis A. (2008) [From Emeritus professors, Thessaloniki, Macedonia, Greece]

“Hippocrates is considered to be the father of modern medicine because in his books, which are more than 70. He described in a scientific manner, many diseases and their treatment after detailed observation. He lived about 2400 years ago. He was born in the island of Kos and died at the outskirts of Larissa at the age of 104. Hippocrates taught and wrote under the shade of a big plane tree, its descendant now is believed to be 500 years old, the oldest tree in Europe-platanus orientalis Hippocraticus- with a diameter of 15 meters.”

“Hippocrates saved Athens from a plague epidemic and for that was highly honored by the Athenians. He considered Democritus-the father of the atomic theory- to be his teacher and after visiting him as a physician to look after his health, he accepted no money for this visit.”

“Some of his important aphorisms were: "As to diseases, make a habit of two things -to help or at least to do no harm". Also: "Those by nature over weight, die earlier than the slim.", also, "In the wounds there are miasmata causing disease if entered the body". He used as a pain relief, the abstract from a tree containing what he called "salycasia", like aspirin. He described for the first time epilepsy not as a sacred disease, as was considered at those times, but as a hereditary disease of the brain and added: "Do not cut the temporal place, because spasms shall occur on the opposite area". According to Hippocrates, people on those times had either one or two meals (lunch and dinner). He also suggested: "...little exercise...and walk...do not eat to saturation". Also he declared: "Physician must convert or insert wisdom to medicine and medicine to wisdom". If all scientists followed this aphorism we would have more happiness on earth.”[16]

- Totelin LM (2007) [From: Department of History and Philosophy of Science, University of Cambridge, Cambridge, UK.]

- The author assert in the Introduction: "The compilers of the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises, active at the end of the fifth century bc or at the beginning of the fourth century bc [citation] considered that too little intercourse could only damage the health of women. In their opinion, women are never healthier than when they are pregnant.[citation]. When women do not have enough sex, they do not get the beneficial moisture that is sperm; their wombs risk drying up and start moving around their bodies, wreaking havoc.[citation]. Diseases caused by a displaced womb mostly affect women who do not have frequent sexual intercourse: virgins, young widows and old women.[citation] For the Hippocratics, the 'obvious' treatment for displacements of the womb and for many other gynaecological ailments is sexual intercourse.[citation]

- —Totelin's Abstract reads:

The compilers of the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises often recommend sexual intercourse as part of treatments for women's diseases. In addition, they often prescribe the use of ingredients that are obvious phallic symbols. This paper argues that the use of sexual therapy in the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises was more extended than previously considered. The Hippocratic sexual therapies involve a series of vegetable ingredients that were sexually connoted in antiquity, but have since lost their sexual connotations. In order to understand the sexual signification of products such as myrtle and barley, one must turn to other ancient texts, and most particularly to Attic comedies. These comedies serve here as a semiotic guide in decoding the Hippocratic gynaecological recipes. However, the sexual connotations attached to animal and vegetable ingredients in these two genres have deeper cultural and religious roots; both genres exploited the cultural material at their disposal.[17]

- Smith CM. (2005) [From School of Medicine and Biomedical Sciences, State University of New York at Buffalo, Buffalo, New York]

- —Author asserts: "Many writers, if not the majority, believe incorrectly that the author of this aphorism was Hippocrates; many believe, also incorrectly, that it will be found in the Hippocratic Oath." [For example see Introduction section of article by Pappas et al. [7], who assert "....(primum non nocere) Hippocrates’ advice, meaning "first do no harm"."].

- —Smith's Abstract reads:

The so-called Hippocratic injunction to do no harm has been an axiom central to clinical pharmacology and to the education of medical and graduate students. With the recent reexamination of the nature and magnitude of adverse reactions to drugs, the purposes of this research and review were to discover the origin of this unique Latin expression. It has been reported that the author was neither Hippocrates nor Galen. Searches of writings back to the Middle Ages have uncovered the appearance of the axiom as expressed in English, coupled with its unique Latin, in 1860, with attribution to the English physician, Thomas Sydenham. Commonly used in the late 1800s into the early decades of the 1900s, it was nearly exclusively transmitted orally; it rarely appeared in print in the early 20th century. Its applicability and limitations as a guide to the ethical practice of medicine and pharmacological research are discussed. Despite insufficiencies, it remains a potent reminder that every medical and pharmacological decision carries the potential for harm.[18]

- Ventegodt S, Clausen B, Omar HA, Merrick J. (2006) [From: the Nordic School of Holistic Health and Quality of Life Research Center in Copenhagen, Denmark; Nordic School of Holistic Medicine; the Kentucky Clinic University of Kentucky in Lexington.; Center for Multidisciplinary Research in Aging, Zusman Child Development Center, Division of Pediatrics and Community Health at the Ben Gurion University, Beer-Sheva, Israel]

- —Excerpts from the article:

Studies from different western countries indicate an incidence of about 15% of girls being assaulted sexually in childhood[8,9,10] and many of these girls are likely to demonstrate severe pelvic problems in their youth. Sexual and gynecological problems resistant to standard therapy are typically problems with acceptance of own sex and sexuality, which do not have to originate from abuse. As originally suggested by Masters and Johnson, they can be a result of not having received the loving acceptance and touch needed in childhood[2,11].....The Hippocratic (Hippocrates, 460–377 BCE) physician was aware of these diseases and his treatment included different physical procedures focused on the female pelvis, like smoking the vagina and massaging the pelvis[12]. The reason why these treatments were later condemned are debated; some authors find it a form of sexual abuse of the woman by the medical profession with an insufficient ethic[13].....When it comes to the practice of pelvic massage, we might be at the essence of medical ethics and the ability to perform this procedure place.[19]

References and notes cited in text

- Links in blue font.

- ↑ Jouanna J. (1999) Hippocrates. Translated by M.B. DeBevoise. The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5907-7

- ↑ Regarding Ionia:

- Note: Ancient geographers gave the label Ionia to the western area along the coast of Asia Minor and the adjacent islands in the Aegean Sea because of its heavy population of Greeks who called themselves Ionians. The Ionian Greeks had emigrated from the Greek mainland and colonized the area shortly after the Trojan War, thought to have occurred in the 1200s or late 1100s BCE. A dozen main cities comprised a cooperative Ionic League. In the 600s and 500s BCE, the Ionians made major contributions to Greek culture, especially in art, literature and philosophy.

- ↑ The Persian Letters. Page 18. In. Hippocrates: Pseudoepigraphic Writings. Translated with an Introduction by Wesley D. Smith. E.J. Brill Leiden, New York, Kobenhavn, Koln. 1990.

- ↑

- Regarding parenthetical quotes:

- ↑ Ventegodt,S.; Kandel,I.; Merrick,J. (2007) A short history of clinical holistic medicine. ScientificWorldJournal 7:1622-1630.PMID 17982604

- Abstract: Clinical holistic medicine has its roots in the medicine and tradition of Hippocrates. Modern epidemiological research in quality of life, the emerging science of complementary and alternative medicine, the tradition of psychodynamic therapy, and the tradition of bodywork are merging into a new scientific way of treating patients. This approach seems able to help every second patient with physical, mental, existential or sexual health problem in 20 sessions over one year. The paper discusses the development of holistic medicine into scientific holistic medicine with discussion of future research efforts,

- ↑ Sigerist HE. (1934) On Hippocrates. Bulletin of the History of Medicine 2:190-214.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Pappas,G.; Kiriaze,I.J.; Falagas,M.E. (2008) Insights into infectious disease in the era of Hippocrates. Int.J.Infect.Dis. PMID 18178502

- Abstract: Hippocrates is traditionally considered the father of modern medicine, still influencing, 25 centuries after his time, various aspects of medical practice and ethics. His collected works include various references to infectious diseases that range from general observations on the nature of infection, hygiene, epidemiology, and the immune response, to detailed descriptions of syndromes such as tuberculous spondylitis, malaria, and tetanus. We sought to evaluate the extent to which this historical information has influenced the modern relevant literature. Associating disease to the disequilibrium of body fluids may seem an ancient and outdated notion nowadays, but many of the clinical descriptions presented in the Corpus Hippocraticum (Hippocratic Collection) are still the archetypes of the natural history of certain infectious diseases and their collective interplay with the environment, climate, and society. For this reason, modern clinicians and researchers continue to be attracted to these 'lessons' from the past - lessons that remain extremely valuable.

- ↑ Chang A, Lad EM, Lad SP. (2007) Hippocrates' influence on the origins of neurosurgery. Neurosurg.Focus. 23:E9 PMID 17961056

- Abstract: Hippocrates is widely considered the father of medicine. His contributions revolutionized the practice of medicine and laid the foundation for modern-day neurosurgery. He inspired several generations to follow his vision, by pioneering the rigorous clinical evaluation of cranial and spinal disorders and combining this approach with a humanistic and ethical perspective focused on the individuality of the patient. His legacy has forever shaped the field of medicine and his cumulative works on head injuries and spinal deformities led to the basic understanding of many of the fundamental neurosurgical principles in use today.

- ↑ "Hippocrates of Cos" in Scientists: Their Lives and Works, Vols 1–7. Online Edition. U*X*L, 2004. Reproduced in Biography Resource Center. Farmington Hills, Mich.: Thomson Gale. 2007. Document Number:K2641500095.

- ↑ Greek Medicine. History of Medicine Division, National Library of Medicine, National Institutes of Health

- Note: From the website” “Asclepius did not begin as a god, however. It is now thought that he was an actual historical figure, renowned for his healing abilities. When he and his sons, Machaon and Podalirios, are mentioned in The Iliad in approximately the 8th century B.C.E., they are not gods. As his "clan" of followers grew, he was elevated to divine status, and temples were built to him throughout the Mediterranean world well into late antiquity .”

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Prioreschi P. (1996) The History of Medicine. Volume II: Greek Medicine. 2nd ed. Horatius Press, Omaha. ISBN 1888456027

- ↑ Scoon R. (1928) Greek Philosophy before Plato. Princeton University Press. Princeton, NJ.

- ↑ Parry, Richard, "Empedocles", The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Spring 2005 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <http://plato.stanford.edu/archives/spr2005/entries/empedocles/>.

- ↑ Pettis JB. (2006) Earth, Dream, and Healing: The Integration of Materia and Psyche in the Ancient World. Journal of Religion and Health, Vol. 45, No. 1

- Excerpt: "Hippocrates’s concerns himself specifically with the study and treatment of the human body, thus separating medicine from philosophical speculation about the natural world such as atomic theory in the thought of Epicurus (371–270 BCE). Apparently, Hippocrates had direct association with the Asclepius temple at Cos, and according to A. J. Brock, he revitalized the Asclepius temple system of his time ([cites] Brock 1916, x)."

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Lonie IM. (1981) The Hippocratic Treatises; "On Generation"; "On the Nature of the Child"; "Diseases IV": A Commentary. Walter de Gruyter, Berlin & New York. ISBN 3110079038

- ↑ Grammaticos PC, Diamantis A. (2008) Useful known and unknown views of the father of modern medicine, Hippocrates and his teacher Democritus. Hell J Nucl Med. 11(1):2-4. PMID 18392218

- ↑ Totelin LM. (2007) Sex and vegetables in the Hippocratic gynaecological treatises. Stud.Hist Philos.Biol.Biomed.Sci. 38:531-540. PMID 17893063

- ↑ Smith CM. (2005) Origin and uses of primum non nocere--above all, do no harm! J.Clin.Pharmacol. 45:371 PMID 15778417

- ↑ Ventegodt S, Clausen B, Omar HA, and Merrick J. (2006) [http://dx.doi.org/ 10.1100/tsw.2006.337 Clinical holistic medicine: holistic sexology and acupressure through the vagina (Hippocratic pelvic massage). ‘’TSW Holistic Health & Medicine’ 1:114–127.

- Note: This article includes a general discussion of the concept and practice of holistic medicine.