British interim government (May–July 1945): Difference between revisions

John Leach (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

John Leach (talk | contribs) m (John Leach moved page Churchill caretaker ministry (May–July 1945) to British interim government (May–July 1945): accuracy and scope) |

Revision as of 23:27, 12 July 2023

The Churchill caretaker ministry, in office from 23 May to 26 July 1945, was a short-term British government during the latter stages of the Second World War. It succeeded the national coalition formed by Winston Churchill after he was first appointed Prime Minister on 10 May 1940. The coalition had comprised leading members of the Conservative, Labour and Liberal parties and it was terminated soon after the defeat of Nazi Germany.

A general election was to be held on 5 July, the first since 1935, although the result could not be announced until 26 July because extra time was needed to collect the large numbers of votes by overseas service personnel. The Conservatives still held a large majority in the House of Commons, and so King George VI asked Churchill to form a temporary ministry until the election was completed. Although the caretaker government continued to fight the war against Japan in the Far East, Churchill's focus was on preparation for the Potsdam Conference where he, accompanied by Clement Attlee and Anthony Eden, would meet Joseph Stalin and Harry Truman.

The main concern on the home front, however, was post-war recovery including the need for reform in key areas such as education, health, housing, industry and social welfare. Campaigning mostly on those issues, the parties canvassed for support in the general election which resulted in a landslide victory for Labour. Churchill thereupon resigned as Prime Minister and was succeeded by his erstwhile coalition deputy Attlee, who formed a Labour government.

Background

The 1935 general election had resulted in a Conservative victory with a substantial majority and Stanley Baldwin became Prime Minister.[1] In May 1937, Baldwin retired and was succeeded by Neville Chamberlain who continued Baldwin's foreign policy of appeasement in the face of German, Italian and Japanese aggression.[2] Having signed the Munich Agreement with Hitler in 1938, Chamberlain became alarmed by the dictator's continuing aggression and, in March 1939, signed the Anglo-Polish military alliance which supposedly guaranteed British support for Poland if attacked.[3] Chamberlain issued the declaration of war against Nazi Germany on 3 September 1939 and formed a war cabinet which included Churchill (out of office since June 1929) as First Lord of the Admiralty.[4]

Dissatisfaction with Chamberlain's leadership became widespread in the spring of 1940 after Germany successfully invaded Norway. In response, the House of Commons held the Conduct of the War debate from 7 to 9 May. At the end of the second day, the Labour opposition forced a division which was in effect a motion of no confidence in Chamberlain. The government's majority of 213 was reduced to 81, still a victory but in the circumstances a shattering blow for Chamberlain.[5]

Two days later on Friday, 10 May, Germany launched its invasion of the Netherlands and Belgium. Chamberlain had been contemplating resignation but then changed his mind because he felt a change of government at such a time would be inappropriate.[6] Later that day, the Labour Party decided that they would not join a national coalition under Chamberlain's leadership but agreed to do so under a different Conservative leader.[7] Chamberlain now resigned and advised the King to appoint Churchill as his successor. Churchill quickly created the national coalition, granting key roles to leading figures in the Labour and Liberal parties.[8] The coalition held firm despite some critical setbacks and, ultimately, in alliance with the Soviet Union and the United States, Britain was able to defeat Germany.[9]

Plans to extend the coalition

In October 1944, Churchill had addressed the House of Commons and moved to extend Parliament by a further year pending the final defeat of Germany and, if possible, Japan. There had not been a general election since 1935 and Churchill was determined to hold one as soon as hostilities ceased. While he could not accurately predict the end of the war against Japan, he was confident that Germany would be defeated by the summer of 1945 and he told the Commons that "we must look to the termination of the war against Nazism as a pointer which will fix the date of the next general election".[10]

In early April 1945, with victory then imminent in the European theatre of operations, Churchill met his deputy Clement Attlee, who was the leader of the Labour Party, to discuss the future of the coalition. Attlee was due to depart for America on 17 April to attend the San Francisco Conference on creation of the United Nations. Travelling with him were ministers Anthony Eden, Florence Horsbrugh and Ellen Wilkinson. They would be out of the country until 16 May and Churchill assured Attlee that Parliament would not be dissolved in their absence. After VE Day on 8 May, Churchill changed his mind about an early election and decided to propose continuation of the coalition until after the defeat of Japan.[11]

In the meantime, however, Labour's Herbert Morrison, the coalition Home Secretary, had published a declaration called Let Us Face The Future which was effectively a party manifesto for the election. Several leading Conservatives made speeches in response. The electioneering may have been premature and it subsided after the death of Hitler on 30 April but quickly regathered pace after VE Day.[12] On 11 May, Churchill met Morrison and Ernest Bevin, the coalition's Minister of Labour, telling them that he wished to maintain the coalition until Japan had been defeated.[13] Their view, confirmed by Labour's National Executive Committee (NEC), was that the general election should be held in October regardless of the situation in the Far East as it was then widely thought the war against Japan might continue for another 18 months.[14][15] With Labour refusing to extend the coalition beyond October, Churchill began receiving calls from his own party to announce an election in June or July – leading Conservatives like Lord Beaverbrook and Brendan Bracken wanted to cash in on Churchill's personal popularity as "the man who won the war".[16] Labour, on the other hand, wanted Churchill's popularity to subside and, in addition, Morrison pointed out that a new and more accurate register of voters would be available by October.[17]

Attlee and Eden returned from America on 16 May and Attlee met Churchill that evening. While Attlee himself favoured continuation until the defeat of Japan, he was aware that the majority of Labour Party members thought differently.[18][19] Churchill sought a compromise and wrote a letter to the NEC which was amended by Bevin to include a pledge on social reform, but it was not enough. On Sunday, 20 May, the NEC voted for an October election and their resolution was backed overwhelmingly by the conference delegates next day.[20][21] Attlee phoned Churchill with the news and an element of discord arose between the two which was fuelled by Beaverbrook in his newspapers.[22]

At noon on Wednesday, 23 May, Churchill tendered his resignation to the King.[23] He insisted on returning to Downing Street to keep up the pretence that the King had a free choice as to whom to invite to form the next government. He was summoned back to Buckingham Palace at four o'clock and the King asked him to form a new administration pending the outcome of the general election. Churchill accepted.[24][25] It was agreed that Parliament would be dissolved on 15 June and the election would be held on 5 July. With many service personnel out of the country, it was decided that votes would not be counted until 26 July, allowing time to collect the service votes.[26]

Formation of the caretaker government

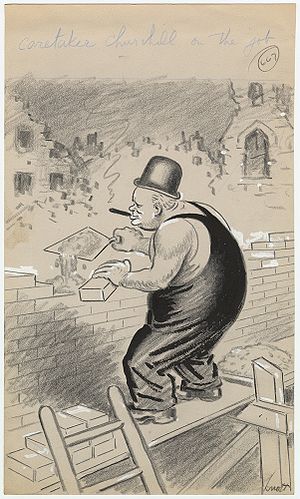

Churchill's new government was known officially as the National Government and unofficially as the Caretaker Ministry. The official title implied a continuation of the Conservative-dominated coalition of the 1930s, especially as it was composed mostly of Conservatives, supplemented by the small National Liberal party and some other individuals like Sir John Anderson who had been associated with that government.[27] Churchill had completed his Cabinet appointments by the morning of 26 May and drove with his wife Clementine to his Woodford constituency where he gave his first speech of the election campaign.[28] He commented on the "caretaker" nickname, saying: "They call us 'the Caretakers'; we condone the title, because it means that we shall take every good care of everything that affects the welfare of Britain and all classes in Britain".[29][30] Churchill was formally reappointed Prime Minister by the King on 28 May.[31]

The Labour and Liberal parties formed the Opposition, except that one Liberal member, Gwilym Lloyd George, accepted Churchill's invitation to continue as Minister of Fuel and Power, the office he had held since 3 June 1942. While Churchill was obliged to replace all the other Labour and Liberal ministers in the coalition, he made no significant changes to the structure of the government. There were just two new posts: a Parliamentary secretary (Peter Thorneycroft) was appointed to the Ministry of War Transport and there was an additional Parliamentary Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs – Lord Lovat was appointed to share the role with future Prime Minister Lord Dunglass.[32]

Domestic events and policies

Pending the general election, Parliament sat on only fourteen days from 29 May to 15 June during the caretaker administration. There was some controversy on Thursday, 7 June, when Churchill refused a demand from the House of Commons to reveal all that was discussed at the Yalta Conference, but said that there were no secret agreements.[33] As confirmed by Hansard, a total of 27 Acts received the Royal Assent on 15 June immediately prior to the Prorogation of Parliament.[34] They all enacted legislation proposed and debated during the term of the wartime administration, among them the Family Allowances Act 1945 which came into effect on 6 August 1946. This Act is important as the first UK law to provide child benefit and it is seen as a tribute to the work done over thirty years by Eleanor Rathbone who championed the family allowance cause.[35] In his closing speech to Parliament, the King said that "legislation has been passed to provide for a scheme of family allowances, in which the families of serving men will be included".[36]

The government was actively involved in monitoring levels of rationing. Key to this was the Ministry of Food under John Llewellin and his parliamentary secretary, Florence Horsbrugh. A number of changes were actioned on 27 May, three weeks after VE Day, including cuts in the bacon ration from 4oz to 3oz per week, in the cooking fat ration from 2oz to 1oz, and a one-eighth cut in the soap ration, except for babies and young children.[37][38] There was good news on 1 June for civilian motorists, though very few people owned private cars in 1945, when the basic petrol ration for civilians was restored. It had been abolished on 1 July 1942 when petrol consumption was restricted to military and industrial use only.[38] There was otherwise very little change with most food products continuing to be rationed as during the war. The same applied to clothing until 1949, and the Utility Clothing Scheme continued under its "Make Do and Mend" ethos.[38]

There was little opportunity within such a short Parliament, and with an election campaign underway, for any effective measures to be brought forward by the caretaker administration and so, for the most part, they kept a watching brief while trying to convince the electorate that they would get down to the real business after the election. With this in mind, a cornerstone of the Conservative manifesto was implementation of the coalition government's Four-Year Plan.[39] According to Martin Gilbert, Churchill was influenced in this by the views of his daughter Sarah.[40] The Four-Year Plan had been prepared two years earlier by William Beveridge and called for the creation of the National Health Service (NHS) and the welfare state. These measures were also part of the Labour manifesto and Churchill, encouraged by Sarah and others, decided to go further by promising free milk for the under-fives and a housing programme to ensure "homes for all".[41] The housing shortage was still the primary domestic issue when Churchill formed his third ministry in 1951 and future prime minister Harold Macmillan was appointed Minister of Housing and Local Government with a commitment to build 300,000 new houses per annum, a target he achieved.[42]

International events

Continuing the war against Japan

The war against Japan continued for the duration of the caretaker ministry and ended on 15 August, three weeks after Churchill's resignation.[43] Even before the defeat of Germany, Churchill had told the Americans that he wanted the Royal Navy to play a prominent role in the defeat of Japan and the liberation of Britain's Asian colonies, especially Singapore. The Americans were unenthusiastic, suspecting that Churchill's intentions were primarily imperialist. Neither Franklin Roosevelt nor Harry Truman had any intention of helping to sustain the British Empire.[44]

In their successful campaigns of 1944 and the early months of 1945, the British Army and its allies had mostly cleared Burma of Japanese forces by May 1945. Rangoon had fallen to the Allies on 2 May following the Battle of Elephant Point. While Churchill hoped for a triumphant re-entry into Singapore,[45] takeover was logistically difficult and it remained under now-friendly Japanese control until 12 September when it was finally recovered by British forces in Operation Tiderace.[46]

Potsdam Conference

Churchill was Great Britain's representative at the post-war Potsdam Conference when it opened on 17 July. It was a "Big Three" event with Joseph Stalin representing the Soviet Union and President Harry Truman the United States. Ever since the conference was first proposed, Churchill had worried about the countries of eastern Europe, especially Poland, which had been overrun by the Red Army.[47] He was accompanied at the sessions not only by Eden as Foreign Secretary but also by Attlee, pending the result of the general election held on 5 July.[48][49] They attended nine sessions in nine days before returning to England for their election counts. After the landslide Labour victory, Attlee returned to Potsdam with Ernest Bevin as the new Foreign Secretary and there were a further five days of discussion.[50]

According to Eden, Churchill's performance at Potsdam was "appalling" because he was unprepared and verbose. Eden said Churchill upset the Chinese, exasperated the Americans and was easily led by Stalin, whom he was supposed to be resisting.[51] This negative version of events is contradicted by Gilbert who describes Churchill's eager involvement in discussions with Stalin and Truman. Their main topics were the successful testing by the Americans of the atom bomb and the demarcation of a new frontier between Poland and East Germany. Stalin insisted on extending the frontier westward to the Oder and Western Neisse rivers, forming the Oder–Neisse line and thus incorporating most of Silesia into Poland. Churchill and Truman opposed this proposal but to no avail. Gilbert does recount that Field Marshal Montgomery was worried about Churchill's health, saying in a letter that Churchill had "put on ten years since I last saw him".[52]

Levant Crisis

Earlier, on 31 May, Churchill and Eden had intervened in the so-called Levant Crisis which had been initiated by French General Charles de Gaulle. Acting as head of France's Provisional Government, de Gaulle had ordered French forces to establish an air base in Syria and a naval base in Lebanon. The action provoked a nationalist outbreak in both countries and France responded with an armed retaliation, leading to many civilian deaths. With the situation escalating out of control, Churchill gave de Gaulle an ultimatum to desist. This was ignored and British forces from neighbouring Transjordan were mobilised to restore order. The French, heavily outnumbered, had no option but to return to their bases. A diplomatic row broke out and Churchill reportedly told a colleague that de Gaulle was "a great danger to peace and for Great Britain".[53]

General election and resignation of Churchill

Churchill mishandled the election campaign by resorting to party politics and trying to denigrate Labour.[54] On 4 June, he committed a serious political gaffe by saying in a radio broadcast that a Labour government would require "some form of Gestapo" to enforce its agenda:[55][56][57]

No Socialist Government conducting the entire life and industry of the country could afford to allow free, sharp, or violently-worded expressions of public discontent. They would have to fall back on some form of Gestapo, no doubt very humanely directed in the first instance.

It backfired badly and Attlee made political capital by saying in his reply broadcast next day: "The voice we heard last night was that of Mr Churchill, but the mind was that of Lord Beaverbrook". Roy Jenkins says that this broadcast was "the making of Attlee".[58] Richard Toye, writing in 2010, says the Gestapo speech had retained all of the notoriety it gained at the time of delivery. Many of Churchill's colleagues and supporters were appalled by it, including Leo Amery who praised Attlee's "adroit reply to Winston's rhodomontade".[59] The broadcast impacted the electorate's perception of Churchill as their national leader, causing him to lose credibility. The problem was that a national leader was expected to behave differently to a party leader during an election and Churchill failed to strike the right balance.[60]

Nevertheless, although the Gestapo speech created a negative response, Churchill personally retained a very high approval rating in opinion polls and was still expected to win the election.[56] The main reason for his defeat was underlying discontent with, and suspicion of, the Conservative party. There was widespread dissatisfaction with the Conservative-dominated government of the 1930s and, recognising the public mood, Labour ran a very effective campaign which focused on the real issues facing the British people in peacetime – the 1930s had been an era of poverty and mass unemployment, so Labour's manifesto promised full employment, improved housing and the provision of free medical services.[56] These issues were foremost in the minds of the voters and Labour was trusted to resolve them.[56]

Churchill's principal theme in the election campaign was always the perils inherent, as he saw them, in socialism, but the Conservatives had to offer an alternative and Churchill stressed to his colleagues that a Conservative government must be constructive.[61] He saw the housing shortage as the main issue and announced his commitment to rebuilding in a broadcast on 13 June but, as with the Gestapo speech on 4 June, he ruined the effect by again insisting that Labour would deploy some form of political police to control the nation.[62] On 3 July, he called for an intensive effort by his Cabinet colleagues to promote housebuilding[63] and prepare legislation for both national insurance and the NHS, but his concerns in these areas were unknown by the electorate to the extent that, when he addressed an audience in the Labour stronghold of Walthamstow that evening, he was almost forced to abandon the event because of booing and heckling.[64] Many commentators felt that Churchill's election speeches lacked "vim" and there is a view that he was much more interested in what was happening in eastern Europe than in Great Britain, but eastern Europe was Churchill's primary concern at Potsdam.[65]

Polling day was on 5 July and, after the agreed delay for collection of the overseas service votes, the results were declared on 26 July.[66] The outcome was a landslide victory for the Labour Party with a Commons majority of 146 over all other parties.[67] Churchill had a constitutional right to remain in office until defeated by a no confidence vote in the House of Commons. He wanted to exercise this right, partly so he could return to Potsdam as Prime Minister, but was instead persuaded to resign that evening and be succeeded by Attlee.[68][69][70][71]

Cabinet

This table lists those ministers who held Cabinet membership in the caretaker ministry.[32] Many retained roles they held in the war ministry and these are marked in situ with the date of their original appointment. For new appointments, their predecessor's name is given. Unless otherwise stated, all were members of the Conservative Party.

Ministers who held Cabinet membership, 23 May – 26 July 1945

Ministers outside the Cabinet

This table lists those ministers who held non-Cabinet roles in the caretaker ministry.[32] Some retained roles they held in the war ministry and these are marked in situ with the date of their original appointment. For new appointments, their predecessor's name is given. Unless otherwise stated, all were members of the Conservative Party.

Government ministers who held offices without Cabinet membership, 23 May – 26 July 1945

Legacy

The caretaker ministry's short term of office means that a critical assessment of its performance is difficult but Stuart Ball credits Churchill as "a good constructor of cabinets" and says that, although the 1945 government is sometimes unfairly dismissed, "it was a sound and capable team".[72] Gilbert points out that the ministry's efforts were overshadowed by the general election in which Churchill himself was the focus of public interest.[73]

References

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 485–486.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 514–515.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 543.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 551–552.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 576–582.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 583.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 586.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 586.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 585.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 356.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, pp. 356–357.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 357.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 358.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 358.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 401.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 356.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 401.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 358.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 402.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 359.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 402.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 360.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, pp. 845–846.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 846.

- ↑ Roberts, Andrew (2018). Churchill: Walking with Destiny. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 978-02-41205-63-1.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 360.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 364.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 846.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 364.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 846.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 360.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 Butler & Butler 1994, pp. 17–20.

- ↑ Leonard, Thomas M. (1977). Day By Day: The Forties. New York: Facts On File, Inc.. ISBN 978-0-87196-375-8.

- ↑ Royal Assent. Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 411, cols 1904–1905 (15 June 1945).

- ↑ Cross, Rupert (October 1946). "The Family Allowances Act, 1945". The Modern Law Review 9 (3): 284–289.

- ↑ His Majesty's Most Gracious Speech. Hansard, House of Commons, 5th Series, vol. 411, cols 1905–1910 (15 June 1945).

- ↑ Tingle, Rory. 75 years on from rationing, what did we learn?, Independent Digital News & Media Limited, 8 January 2015.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Zweiniger-Bargielowska, Ina (March 1994). "Rationing, Austerity and the Conservative Party Recovery after 1945". The Historical Journal 37 (1): 173–197.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 847.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 847.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 847.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 844–845.

- ↑ Text of Hirohito's Radio Rescript, The New York Times, 15 August 1945, p. 3.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 756.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 756.

- ↑ Park, Keith (August 1946). Air Operations in South East Asia 3rd May 1945 to 12th September 1945. War Office. published in Template:London Gazette

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, pp. 848–849.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 404.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 848.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 795–796.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 796.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, pp. 850–854.

- ↑ Fenby, Jonathan (2011). The General: Charles de Gaulle and the France he saved. London: Simon & Schuster, 42–47. ISBN 978-18-47394-10-1.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. =791–795.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 792.

- ↑ 56.0 56.1 56.2 56.3 Addison, Paul (17 February 2011). Why Churchill Lost in 1945. BBC History. BBC.

- ↑ Toye 2010, p. 655.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, p. 793.

- ↑ Toye 2010, pp. 655–656.

- ↑ Toye 2010, pp. 679–680.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, pp. 846–847.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 847.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 413.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 849.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, pp. 847–848.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, p. 360.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 855.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 855.

- ↑ Hermiston 2016, pp. 366–367.

- ↑ Jenkins 2001, pp. 798–799.

- ↑ Pelling 1980, p. 408.

- ↑ Ball, Stuart (2001). "Churchill and the Conservative Party". Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 11.

- ↑ Gilbert 1991, p. 849.

Provenance

- Some content on this page may previously have appeared on Wikipedia.

This article was wholly revised and then expanded by me between 18 July 2019 and 7 March 2021. After completion of further revisions in due course, it will be in order to remove the attribution tag. John (talk) 23:57, 9 June 2023 (CDT)