Mahatma Gandhi: Difference between revisions

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) m (Pat Palmer moved page Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi to Mahatma Gandhi without leaving a redirect) |

Pat Palmer (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

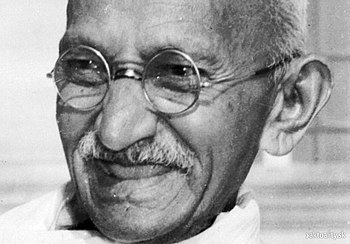

{{Image|Mahatma Gandhi, close-up portrait.jpg|right|350px|Mahatma Gandhi (made sometime before 1942).}} | {{Image|Mahatma Gandhi, close-up portrait.jpg|right|350px|Mahatma Gandhi (made sometime before 1942).}} | ||

''' | '''Mahatma Gandhi''' (1869–1948) was an Indian lawyer, trained in [[Great Britain]], who led a decades-long, non-violent campaign that culminated in [[India]]'s 1947 independence from British rule. Earlier in his life, he also led a campaign of non-violent civil disobedience in South Africa. Both campaigns were an important source of inspiration to [[Martin Luther King Jr.]], who led a similar campaign of non-violent resistance to the injustices of racism in the [[United States of America|U.S.]]. For his adherence to simple living and non-violence, Gandhi was known in later life by the title of Mahatma (great soul) instead of by his birth name, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi. | ||

== Early life == | == Early life == | ||

Revision as of 14:18, 2 March 2023

Mahatma Gandhi (1869–1948) was an Indian lawyer, trained in Great Britain, who led a decades-long, non-violent campaign that culminated in India's 1947 independence from British rule. Earlier in his life, he also led a campaign of non-violent civil disobedience in South Africa. Both campaigns were an important source of inspiration to Martin Luther King Jr., who led a similar campaign of non-violent resistance to the injustices of racism in the U.S.. For his adherence to simple living and non-violence, Gandhi was known in later life by the title of Mahatma (great soul) instead of by his birth name, Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi.

Early life

He was born on 2 October 1869, in Porbandar, a princely state in Gujarat, where his father was diwan (chief minister). He was the youngest child in the family. At the age of 12 he married the uneducated Kastur (Kasturba) Makanji Kapadia. His father died when he was 16, Mohandas having spent much time in nursing him. In 1888 he went to London to study law, supported by his elder brother. During the period in London he read the Bhagavad Gita for the first time. It made a deep impression on him, and he regarded it as his spiritual reference book thereafter.[1] He qualified as a barrister at the Inner Temple.[2]

South Africa

On return from England, he failed to get clients in Bombay, but derived a small income from drafting memorials and applications. In 1893 he was offered a job in South Africa, in relation to a case where his employer, who knew no English, was employing British lawyers. He persuaded his employer, who was in Natal, and his opponent, who was in the Transvaal, to settle the case through arbitration, and afterwards became involved in a campaign to try to stop a bill in the Natal Assembly to deny the vote to Indians. The Indian community in Natal guaranteed him an income as a barrister to get him to stay on as secretary of the Natal Indian Congress.[3] In addition to his law work he acted as propagandist for the Indian community, presenting it as the natural partner to the Europeans, as coming from an ancient civilisation.[4] Having gone to India in 1896 to collect his wife and family, he was nearly lynched on his return by some of the white people furious at the publicity he had given to Indians' problems in South Africa. In 1899 he raised a short-lived ambulance corps of Indian volunteers to help the British side in the Boer War.[5]

In 1901, he briefly returned to India. After attending a session of the Indian National National Congress, he tried to practise as a barrister, but returned to South Africa in order to help confront the new difficulties facing Indians in the Transvaal, where he set up as a barrister in Johannesburg. In 1903 he backed the founding of a weekly Indian newspaper, Indian Opinion and began to play a major part in its running. He also set up an elaborate “simple” lifestyle, an ashram community, in accordance with the ideas of John Ruskin.[6]

Gandhi responded to the Zulu rebellion by lobbying for the creation of an Indian stretcher bearer corps and also a Volunteer Corps to serve against the "Kafirs", as he called them. The stretcher bearer corps was created and led by him with the rank of Sergeant Major. This served for just under a month.[7] In 1907 the Transvaal passed a law imposing conditions and restrictions on the Indian community, and the Satyagraha (usually translated truth-force) movement started in opposition to this, the majority of the Indian population refusing to comply. The campaign of civil disobedience on its own did not succeed. Following the formation of the Union of South Africa, some laws were changed or repealed and new ones imposed. A new campaign targeted the tax on former indentured labourers. The savage repression of this non-violent campaign produced a reaction in India and Britain, and the South African government was forced to make major concessions. Gandhi left South Africa in 1914.[8]

Gandhi in India

On arrival in India (via England) in 1915, Gandhi had many meetings with nationalist leaders and others before setting up an ashram near Ahmedabad. This had rules emphasising its ascetically religious character, but it was also to be a political base and to exemplify the campaign against the use of imported cotton by promoting homespun. He also began to change his clothing: the once dapper lawyer by various stages took to wearing a short dhoti. He soon became the leading figure in the Indian National Congress. He used leaflets and periodicals to disseminate his message.[9] At this time, although speaking out against the idea of untouchability, he was still defending the caste system. For instance, in 1922 he published an article defending it as essential to Hinduism[10] and in the same year he wrote that he would rather abandon Home Rule than abandon the untouchables.[11] He led a successful campaign with peasant farmers who had major grievances in north Bihar in 1917, and a semi-successful one in 1918 in Gujarat. In a workers' dispute in Ahmedabad he first used fasting as a lever to gain a result. He participated in a recruitment drive for the war, which precipitated a conflict between his desire to support the Empire and his developing belief in non-violence. The first attempt at an India-wide campaign – against anti-sedition laws – degenerated into violence.[12]

The British reaction against this violence, and the alienation of Indian Muslims by British actions against Turkey gave Gandhi the opportunity to strive for Hindu-Muslim unity in a campaign for non-cooperation. This took various forms, including a boycott of the Raj's colleges, in place of which new ones were founded. There were constant disagreements among the leadership, but Gandhi usually got his way, though he could not prevent more violence. In 1922 he was sentenced to six years imprisonment on a charge, which he admitted, of inciting disaffection.[13]

Within two years he was released on grounds of ill health, but before the end of 1924 undertook a 21-day fast in response to clashes between Muslims and Hindus. He started no campaigns during what would have been the remainder of his sentence, but in 1930 a series of actions, well-publicised internationally, led to another imprisonment, this time without trial. Eventually he was released, and negotiations with the viceroy led to a compromise agreement. It was in relation to this that Churchill made his well-known remark: "It is alarming and also nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple1 lawyer, now posing as a fakir of a type well known in the East, striding half-naked up the steps of the viceregal palace, while he is still organising and conducting a defiant campaign of civil disobedience, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King-Emperor." At a round table conference in London, Gandhi clashed with Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar, an untouchable, both of them claiming leadership of the untouchables, Ambedkar wanting a separate electorate. The conference reached no agreement and on return to India Gandhi was arrested as part of a widespread repression which included the banning of the Congress. While in prison he undertook a dangerous fast against the principle of a separate electorate for untouchables and for the integration of untouchables into Hindu society. He succeeded in bring in some localised changes to practice, and conceded the idea of reserved seats but not a separate electorate.[14]

In 1934, released, Gandhi broke up his ashram, abandoned the non-cooperation campaign and withdrew from the Congress, though he continued to exercise great influence on it. In 1935 he also renounced his support for the caste element in Hinduism, a declaration which swayed some and bitterly antagonised others.[15] The outbreak of World War 2 in 1939 led Gandhi (though with no official position) into further talks with the viceroy and with Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, who now began to look on Congress as the enemy of the Muslims, and in 1940 called for the formation of a separate Muslim nation-state to be called Pakistan. The Raj, following its policy of divide and rule, made concessions to the League. Gandhi, torn between support for Britain and his belief in non-violence, initiated a civil disobedience campaign for free speech.

In 1942, after the failure of demands over Dominion status, he produced the simple demand to Quit India. He was again imprisoned. This, and the government crackdown on Congress, gave rise to a wave of civil disobedience, strikes and violence. Gandhi fasted but was persuaded to break the fast.

Gandhi's wife Kasturba died in the prison. Gandhi had not been a good family man. Often domineering, often neglectful, he admitted that he had not been a good husband,[16] and he had alienated his eldest son, though his other three sons were devoted to him. Nevertheless Mohandas and Kasturba had become very attached to each other (and she may have saved his life by persuading him to drink goat's milk, when he had vowed not to drink cow's milk). Her death left him subject to fits of depression. He was later released on the grounds that he was dying.[17]

When, at the end of the war, the Labour government came to power in Britain, Clement Attlee announced that India would be granted independence, and three ministers came out to discuss how this would be done. Gandhi asserted himself to ensure that Jawaharlal Nehru would lead the Congress delegation. He was not a participant in the talks himself but played or tried to play an influential role at key moments.[18]

Abandoning the centres of government, in 1946 he went with his entourage to spend time in the Noakhali district of Bengal, a scene of Muslim violence against Hindus, where he walked from village to village.[19] No longer consulted by the Congress leadership, he nevertheless intervened at various points, but without effecting decisive changes. He also continued to work for Hindu-Muslim reconciliation in different areas, and seems to have succeeded in preventing large-scale rioting and slaughter, as happened in the Punjab, from happening in Bengal.

Final days

He came to Delhi and, with violence continuing, started a fast for a reunion of hearts of all communities. He achieved sufficient results for him to abandon it after six days. He now intended to go to Pakistan, but on 30 January 1948 was assassinated by Nathuram Godse, a member of a small conspiracy, who later said that he hated non-violence and any sympathy for Muslims, and that Gandhi had weakened Hindu society.[20]

The worldwide outpouring of grief at his death was huge, and his funeral march was covered by international media. Condolences poured in from world leaders and from luminaries such as Albert Einstein. A massive crowd followed his body on parade down the major streets of Delhi. The scene was immortalized in the 1981 film by Richard Attenborough, Gandhi.

Notes

1. Incorrect. Gandhi was an Inner Temple lawyer

References

- ↑ Fischer, L. Ghandi: His life and message for the world. New American Libary. 1954

- ↑ Gandhi, Rajmohan. Gandhi: the man, his people, and the Empire. Haus Publishing. 2007. chs 1-2

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 3

- ↑ Singh, G B. Gandhi: Behind the mask of divinity. Prometheus Books. 2004. pp 181-6

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 3

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 4

- ↑ Singh, G B. chs 9-10

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 6

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 7

- ↑ Singh, G B. pp 249-51

- ↑ Gandhi, R. p 237

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 7

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 8

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 10

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 11

- ↑ Gandhi, R. p 218

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 13

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 14

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch 15

- ↑ Gandhi, R. ch16