White Argentine: Difference between revisions

imported>Pablo Martín Zampini No edit summary |

imported>Pablo Martín Zampini No edit summary |

||

| Line 43: | Line 43: | ||

Although the estimates vary, it is a fact that Spanish immigration from the [[Iberian Peninsula|peninsula]] towards the New World was scanty during all the colonial period. Some estimates state that less than 200,000 Spaniards arrived in the Americas during the period 1509-1790.<ref>Luis Vita: ''Introducción a una teoría de la historia para América Latina''. Chapter IV. Editorial Planeta. Buenos Aires, 1992.</ref> On the other hand, Peter Muschamp Boyd-Bowman -an Emeritus Professor of Spanish Linguistics- estimated that about 437,669 Spaniards went and established in the [[Spanish America|American possessions]] between 1506 and 1650; of this total, a figure between 10,500 and 13,125 ''Peninsulares'' settled in the Río de la Plata region during the 18th century.<ref>Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz: ''La población de América Latina desde los tiempos precolombinos al año 2025'', pages 78-80. Alianza Editorial. Madrid, 1994</ref> | Although the estimates vary, it is a fact that Spanish immigration from the [[Iberian Peninsula|peninsula]] towards the New World was scanty during all the colonial period. Some estimates state that less than 200,000 Spaniards arrived in the Americas during the period 1509-1790.<ref>Luis Vita: ''Introducción a una teoría de la historia para América Latina''. Chapter IV. Editorial Planeta. Buenos Aires, 1992.</ref> On the other hand, Peter Muschamp Boyd-Bowman -an Emeritus Professor of Spanish Linguistics- estimated that about 437,669 Spaniards went and established in the [[Spanish America|American possessions]] between 1506 and 1650; of this total, a figure between 10,500 and 13,125 ''Peninsulares'' settled in the Río de la Plata region during the 18th century.<ref>Nicolás Sánchez Albornoz: ''La población de América Latina desde los tiempos precolombinos al año 2025'', pages 78-80. Alianza Editorial. Madrid, 1994</ref> | ||

{{Image|Manuelbelgrano.jpg|left| | {{Image|Manuelbelgrano.jpg|left|170px|General [[Manuel Belgrano]] (1770-1820), creator of the [[Argentine flag]]; his father was born in [[Liguria]], and his mother was a ''criolla'' from [[Santiago del Estero]].}} | ||

It was not until the creation of the [[Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata]] in [[1776]], that the first censuses with classification into ''[[casta]]s'' were conducted. The [[1778]] Census ordered by [[viceroy]] [[Juan José de Vértiz y Salcedo|Juan José de Vértiz]] in [[Buenos Aires]] revealed that, of a total population of 37,130 inhabitants (including both city and surrounding countryside), the Spaniards and [[Criollo people|Criollos]] numbered 25,451, or 68.55% of the total. Another census carried out in the Corregimiento de [[Cuyo (Argentina)|Cuyo]] in 1777 showed that the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 4,491 (or 51.24%) out of a population of 8,765 inhabitants. In [[Córdoba, Argentina|Córdoba]] (city and countryside) the Spanish/Criollo people comprised a 39.36% (about 14,170) of 36,000 inhabitants.<ref name= "colonial census">[http://www.revisionistas.com.ar/?=4283 Revisionistas. La Otra Historia de los Argentinos] Source: ''Argentina: de la Conquista a la Independencia.'' by C. S. Assadourian – C. Beato – J. C. Chiaramonte. Ed. Hyspamérica, Buenos Aires. (1986)</ref> | It was not until the creation of the [[Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata]] in [[1776]], that the first censuses with classification into ''[[casta]]s'' were conducted. The [[1778]] Census ordered by [[viceroy]] [[Juan José de Vértiz y Salcedo|Juan José de Vértiz]] in [[Buenos Aires]] revealed that, of a total population of 37,130 inhabitants (including both city and surrounding countryside), the Spaniards and [[Criollo people|Criollos]] numbered 25,451, or 68.55% of the total. Another census carried out in the Corregimiento de [[Cuyo (Argentina)|Cuyo]] in 1777 showed that the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 4,491 (or 51.24%) out of a population of 8,765 inhabitants. In [[Córdoba, Argentina|Córdoba]] (city and countryside) the Spanish/Criollo people comprised a 39.36% (about 14,170) of 36,000 inhabitants.<ref name= "colonial census">[http://www.revisionistas.com.ar/?=4283 Revisionistas. La Otra Historia de los Argentinos] Source: ''Argentina: de la Conquista a la Independencia.'' by C. S. Assadourian – C. Beato – J. C. Chiaramonte. Ed. Hyspamérica, Buenos Aires. (1986)</ref> | ||

| Line 51: | Line 51: | ||

Although being a minority in demographics terms, the Criollo people played a leading role in the [[May Revolution|independentist movement that started in 1810]] and led to the [[independence of Argentina]] from Spain in [[1816]]. Argentine national heroes such as [[Manuel Belgrano]] and [[José de San Martín]], military men as [[Cornelio Saavedra]], [[José Rondeau]], [[Carlos María de Alvear]] and [[Miguel de Azcuénaga]], and politicians as [[Juan José Paso]], [[Mariano Moreno]], [[Juan José Castelli]], and [[Gervasio Posadas]] were mostly Criollos of Spanish, Italian or French descent; some Spaniards also collaborated with the movement, as [[Domingo Matheu]] and [[Juan Larrea]]. Nevertheless, the war effort fell on the [[Mestizo]], [[Mulatto]] and [[Black people|Black]] populations, who composed most of the troops during the [[Argentine Wars of Independence|wars of independence]], and so they suffered heavy losses of lives, as they were frequently used as "[[cannon fodder]]". | Although being a minority in demographics terms, the Criollo people played a leading role in the [[May Revolution|independentist movement that started in 1810]] and led to the [[independence of Argentina]] from Spain in [[1816]]. Argentine national heroes such as [[Manuel Belgrano]] and [[José de San Martín]], military men as [[Cornelio Saavedra]], [[José Rondeau]], [[Carlos María de Alvear]] and [[Miguel de Azcuénaga]], and politicians as [[Juan José Paso]], [[Mariano Moreno]], [[Juan José Castelli]], and [[Gervasio Posadas]] were mostly Criollos of Spanish, Italian or French descent; some Spaniards also collaborated with the movement, as [[Domingo Matheu]] and [[Juan Larrea]]. Nevertheless, the war effort fell on the [[Mestizo]], [[Mulatto]] and [[Black people|Black]] populations, who composed most of the troops during the [[Argentine Wars of Independence|wars of independence]], and so they suffered heavy losses of lives, as they were frequently used as "[[cannon fodder]]". | ||

{{Image|BartolomeMitre001.JPG|right| | {{Image|BartolomeMitre001.JPG|right|160px|[[Bartolomé Mitre]] (1821-1906), President of Argentina (1862-1868); his family had [[Greek people|Greek]] ancestry, originally surnamed Mitropoulos.<ref>[http://www.dailyfrappe.com/features/interviews/tabid/58/articleType/ArticleView/articleId/4425/Hellenic-Community-of-Argentina.aspx Daily Frappe: Hellenic Community of Argentina]</ref>}} | ||

In 1822, [[Bernardino Rivadavia]] -then Minister of Government of Buenos Aires Province- ordered Ventura Arzac to conduct a new Census in the city, and it showed these results: the city had then 55,416 inhabitants, of which 40,000 were White (about 72.2%). Of this total of Whites, a 90% were Criollos, a 5% were Spaniards, and the other 5% were from other European nations.<ref>Argentina 200 Años. Vol. 9 1820-1830. Editor José Alemán. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino. Buenos Aires. 2010.</ref> | In 1822, [[Bernardino Rivadavia]] -then Minister of Government of Buenos Aires Province- ordered Ventura Arzac to conduct a new Census in the city, and it showed these results: the city had then 55,416 inhabitants, of which 40,000 were White (about 72.2%). Of this total of Whites, a 90% were Criollos, a 5% were Spaniards, and the other 5% were from other European nations.<ref>Argentina 200 Años. Vol. 9 1820-1830. Editor José Alemán. Arte Gráfico Editorial Argentino. Buenos Aires. 2010.</ref> | ||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

{{Main|Immigration in Argentina}} | {{Main|Immigration in Argentina}} | ||

{{Image|JulioArgentinoRoca.JPG|right| | {{Image|JulioArgentinoRoca.JPG|right|180px|General [[Julio A. Roca]], President of the Nation ([[1880]]-[[1886]]); he led the [[Conquest of the Desert]] in [[1879]], that allowed Argentina to occupy new lands for the immigrants to buy and cultivate.}} | ||

In February [[1856]], the municipal government of [[Baradero]] granted lands for the settlement of ten Swiss families in an agricultural colony near that town. Later that year, another colony was founded by Swiss immigrants in [[Esperanza, Santa Fe|Esperanza]], [[Santa Fe Province|Santa Fe]]. In spite of these isolated provincial initiatives, it was not until the [[Argentine Confederation]] and the [[Buenos Aires Province]] definitively unified in [[1862]] -and a strong central government could be established- that Presidents [[Bartolomé Mitre]], [[Domingo Sarmiento]] and [[Nicolás Avellaneda]] implemented policies that encouraged massive European immigration. In [[1876]], during Avellaneda's presidential period, the [[Congress of Argentina|Congress]] voted and sanctioned the new Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization. During the following decades, and until the mid-twentieth century, waves of European settlers came to Argentina. Major contributors included [[Italy]] (initially from [[Piedmont]], [[Veneto]] and [[Lombardy]], later from [[Campania]], [[Calabria]], and [[Sicily]]),<ref>[http://www.feditalia.org.ar/arg/federaciones/feditalia_org_fed_regionales.html Federaciones Regionales] www.feditalia.org.ar</ref> and [[Spain]] (most were [[Galician people|Galicians]] and [[Basque people|Basques]], but there were [[Asturian people|Asturians]], [[Cantabrian people|Cantabrians]], [[Catalan people|Catalans]], and [[Andalusian people|Andalusians]]). | In February [[1856]], the municipal government of [[Baradero]] granted lands for the settlement of ten Swiss families in an agricultural colony near that town. Later that year, another colony was founded by Swiss immigrants in [[Esperanza, Santa Fe|Esperanza]], [[Santa Fe Province|Santa Fe]]. In spite of these isolated provincial initiatives, it was not until the [[Argentine Confederation]] and the [[Buenos Aires Province]] definitively unified in [[1862]] -and a strong central government could be established- that Presidents [[Bartolomé Mitre]], [[Domingo Sarmiento]] and [[Nicolás Avellaneda]] implemented policies that encouraged massive European immigration. In [[1876]], during Avellaneda's presidential period, the [[Congress of Argentina|Congress]] voted and sanctioned the new Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization. During the following decades, and until the mid-twentieth century, waves of European settlers came to Argentina. Major contributors included [[Italy]] (initially from [[Piedmont]], [[Veneto]] and [[Lombardy]], later from [[Campania]], [[Calabria]], and [[Sicily]]),<ref>[http://www.feditalia.org.ar/arg/federaciones/feditalia_org_fed_regionales.html Federaciones Regionales] www.feditalia.org.ar</ref> and [[Spain]] (most were [[Galician people|Galicians]] and [[Basque people|Basques]], but there were [[Asturian people|Asturians]], [[Cantabrian people|Cantabrians]], [[Catalan people|Catalans]], and [[Andalusian people|Andalusians]]). | ||

| Line 201: | Line 201: | ||

=== 2nd immigratory wave after World War II === | === 2nd immigratory wave after World War II === | ||

{{Image|Mauricio-Macri-BAfim-2008.JPG|right| | {{Image|Mauricio-Macri-BAfim-2008.JPG|right|160px|[[Mauricio Macri]] -the Mayor of [[Buenos Aires City]]- is the son of businessman [[Francisco Macri]], who was born in [[Rome]] and emigrated as a young man in 1949.}} | ||

After the [[Second World War]], many Europeans fled to Argentina, escaping the hunger and poverty of the post-war period. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, during the period 1941-1950 at least 392,603 Europeans entered the country: 252,045 Italians, 110,899 Spaniards, 16,784 Poles, 7,373 Russians and 5,538 French.<ref name="immigration post ww2">[http://sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/soc237/papers/cookappendixr.pdf Migration and Nationality Patterns in Argentina.] Source: ''Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 1976''.</ref> Among the notable Italian immigrants in that period were protest singer [[Piero De Benedictis]] (emigrated with his parents in 1948),<ref>[http://www.pieroonline.com/ Piero on line (biografía).] (Spanish)</ref> actors [[Rodolfo Ranni]] (emigrated in 1947)<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2008/02/09/espectaculos/c-01603492.htm Rodolfo Ranni: "Me hice actor para ganar guita."] Diario ''Clarín'' (Spanish)</ref> and [[Gianni Lunadei]] (1950),<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/1998/06/18/e-05601d.htm Se suicidó Gianni Lunadei.] Diario ''Clarín''. (Spanish)</ref> [[César Civita]] (1941),<ref>[http://www.lanacion.com.ar/694574-murio-cesar-civita-el-gran-creador-de-la-editorial-abril Murió César Civita, el gran creador de la editorial Abril.] Diario ''La Nación''. (Spanish)</ref> businessman [[Francisco Macri]] (1949),<ref>[http://www.fundacionkonex.com.ar/b1448-francisco--macri politician Francisco Macri.] Fundación Kónex. (Spanish)</ref> [[Pablo Verani]] (1947),<ref>http://www.fruticulturasur.com/fichaSubNota.php?articuloId=250&subnotaId=124 Corazón de chacarero.''Fruticultura Sur''. (Spanish)</ref> and rock musician [[Los Gatos (band)|Kay Galiffi]] (1950).<ref>http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-4040-2007-08-19.html Mucha madera. Diario ''Página/12''. (Spanish)</ref> | After the [[Second World War]], many Europeans fled to Argentina, escaping the hunger and poverty of the post-war period. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, during the period 1941-1950 at least 392,603 Europeans entered the country: 252,045 Italians, 110,899 Spaniards, 16,784 Poles, 7,373 Russians and 5,538 French.<ref name="immigration post ww2">[http://sscnet.ucla.edu/soc/soc237/papers/cookappendixr.pdf Migration and Nationality Patterns in Argentina.] Source: ''Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, 1976''.</ref> Among the notable Italian immigrants in that period were protest singer [[Piero De Benedictis]] (emigrated with his parents in 1948),<ref>[http://www.pieroonline.com/ Piero on line (biografía).] (Spanish)</ref> actors [[Rodolfo Ranni]] (emigrated in 1947)<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2008/02/09/espectaculos/c-01603492.htm Rodolfo Ranni: "Me hice actor para ganar guita."] Diario ''Clarín'' (Spanish)</ref> and [[Gianni Lunadei]] (1950),<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/1998/06/18/e-05601d.htm Se suicidó Gianni Lunadei.] Diario ''Clarín''. (Spanish)</ref> [[César Civita]] (1941),<ref>[http://www.lanacion.com.ar/694574-murio-cesar-civita-el-gran-creador-de-la-editorial-abril Murió César Civita, el gran creador de la editorial Abril.] Diario ''La Nación''. (Spanish)</ref> businessman [[Francisco Macri]] (1949),<ref>[http://www.fundacionkonex.com.ar/b1448-francisco--macri politician Francisco Macri.] Fundación Kónex. (Spanish)</ref> [[Pablo Verani]] (1947),<ref>http://www.fruticulturasur.com/fichaSubNota.php?articuloId=250&subnotaId=124 Corazón de chacarero.''Fruticultura Sur''. (Spanish)</ref> and rock musician [[Los Gatos (band)|Kay Galiffi]] (1950).<ref>http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/suplementos/radar/9-4040-2007-08-19.html Mucha madera. Diario ''Página/12''. (Spanish)</ref> | ||

| Line 207: | Line 207: | ||

Argentina also received thousands of [[Ethnic Germans|Germans]] who came bankrupt -like [[Oskar Schindler]] and his wife, for example- and [[Ashkenazi Jews]]. Unfortunately, among those "good" Germans there were hundreds of Nazi war criminals; [[Adolf Eichmann]], [[Josef Mengele]], [[Erich Priebke]], [[Rodolfo Freude]] (who became the first director of [[SIDE|Argentine State Intelligence]]), and the [[Ustaše]] Head of State of Croatia, [[Ante Pavelić]] -among others- entered the country in this period. It is still matter of debate whether the Argentine government of the time was aware of the presence of these criminals on Argentine soil or not; but the consequence was that Argentina was considered a Nazi Haven for several decades.<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1881346,00.html Argentina Deports a Holocaust-Denying Bishop]</ref> | Argentina also received thousands of [[Ethnic Germans|Germans]] who came bankrupt -like [[Oskar Schindler]] and his wife, for example- and [[Ashkenazi Jews]]. Unfortunately, among those "good" Germans there were hundreds of Nazi war criminals; [[Adolf Eichmann]], [[Josef Mengele]], [[Erich Priebke]], [[Rodolfo Freude]] (who became the first director of [[SIDE|Argentine State Intelligence]]), and the [[Ustaše]] Head of State of Croatia, [[Ante Pavelić]] -among others- entered the country in this period. It is still matter of debate whether the Argentine government of the time was aware of the presence of these criminals on Argentine soil or not; but the consequence was that Argentina was considered a Nazi Haven for several decades.<ref>[http://www.time.com/time/world/article/0,8599,1881346,00.html Argentina Deports a Holocaust-Denying Bishop]</ref> | ||

{{Image|Galtieri.jpg|left| | {{Image|Galtieri.jpg|left|160px|President ''de-facto'' [[Leopoldo Galtieri]] (1926-2003), of [[Italian people|Italian]] descent.<ref>[[Oriana Fallaci]], Cambio 16, June 1982, Available Online [http://www.malvinasonline.com.ar/notas/nota.php?recordID=222] "''Si, señora periodista, desciendo de italianos. Mis abuelos eran italianos. Mi abuelo de Génova y mi abuela de Calabria. Vinieron aquí con las oleadas de inmigrantes que se produjeron al comienzo de siglo. Eran obreros pobres, pronto hicieron fortuna.''" ("''Yes, madam reporter, I'm descended from Italians. My grandparents were Italian. My grandfather came from Genoa and my grandmother from Calabria. They came here with the waves of immigrants that occurred at the beginning of the century. They were poor workers, they soon made a fortune.''")</ref>}} | ||

White Argentines, therefore, likely peaked as a percentage of the national population at over 90% on or shortly after the 1947 census. The flow of European immigration continued during the 1950s, but -compared to the previous decade- it is evident that it was diminishing considerably. The [[Marshall Plan]] implemented by the [[United States]] to help [[Western Europe]] recover from the consequences of World War II was working, and emigration was not such a necessity. During the period 1951-1960, only 242,889 Europeans entered Argentina: 142,829 were Italians, 98,801 were Spaniards, 934 were French, and 325 were Poles. The next decade (1961–1970), the total amount of European immigrants barely reached 13,363 (9,514 Spaniards, 1,845 Poles, 1,266 French and 738 Russians).<ref name="immigration post ww2" /> | White Argentines, therefore, likely peaked as a percentage of the national population at over 90% on or shortly after the 1947 census. The flow of European immigration continued during the 1950s, but -compared to the previous decade- it is evident that it was diminishing considerably. The [[Marshall Plan]] implemented by the [[United States]] to help [[Western Europe]] recover from the consequences of World War II was working, and emigration was not such a necessity. During the period 1951-1960, only 242,889 Europeans entered Argentina: 142,829 were Italians, 98,801 were Spaniards, 934 were French, and 325 were Poles. The next decade (1961–1970), the total amount of European immigrants barely reached 13,363 (9,514 Spaniards, 1,845 Poles, 1,266 French and 738 Russians).<ref name="immigration post ww2" /> | ||

| Line 223: | Line 223: | ||

Given that the main sources of South American immigrants since the 1960s have been [[Bolivia]], [[Paraguay]] and [[Perú]], most of these immigrants have been either [[Amerindian]] or [[Mestizo]], for these groups represent the ethnic majorities in their countries of origin.<ref name="worldstatesmen bolivia" /><ref name="worldstatesmen peru" /><ref name="worldstatesmen paraguay" /> The increasing numbers of immigrants from these sources has caused the percentage of White Argentines to be reduced significantly in certain areas of the [[Greater Buenos Aires]]; mainly in the ''partidos'' of [[Morón, Buenos Aires|Morón]], [[La Matanza Partido|La Matanza]], [[Escobar Partido|Escobar]] and [[3 de Febrero]], and the ''porteño'' neighbourhoods of [[Flores]], [[Villa Soldati]], [[Villa Lugano]] and [[Pompeya]].<ref name="bolivian settlement in gba" /> Unfortunately, many Amerindian or Mestizo people of Bolivian/Paraguayan/Peruvian origin have suffered either of [[racist discrimination]] and violence<ref>[http://www.pagina12.com.ar/2001/01-06/01-06-02/pag17.htm «A witness narrates how a Bolivian woman was thrown off a train: Tale of a Journey to Xenophobia (Spanish)»] by Cristian Alarcón. Diario ''Página/12'', 2 June 2001.</ref><ref>[http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/sociedad/3-102111-2008-04-09.html «A bullet loaded with racist hatred (Spanish)»], Diario ''Página/12'', 9 April 2008.</ref> or have been victims of [[sexual slavery]]<ref>[http://www.perfilcristiano.com/trata-de-personas-en-argentina/ Human Trafficking in Argentina (Spanish).]</ref> and [[forced labor]] in textile [[sweat shops]].<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2000/07/05/o-02002.htm Forced Labor in Argentina (Spanish)] Diario ''Clarín'', 5 July 2000.</ref> | Given that the main sources of South American immigrants since the 1960s have been [[Bolivia]], [[Paraguay]] and [[Perú]], most of these immigrants have been either [[Amerindian]] or [[Mestizo]], for these groups represent the ethnic majorities in their countries of origin.<ref name="worldstatesmen bolivia" /><ref name="worldstatesmen peru" /><ref name="worldstatesmen paraguay" /> The increasing numbers of immigrants from these sources has caused the percentage of White Argentines to be reduced significantly in certain areas of the [[Greater Buenos Aires]]; mainly in the ''partidos'' of [[Morón, Buenos Aires|Morón]], [[La Matanza Partido|La Matanza]], [[Escobar Partido|Escobar]] and [[3 de Febrero]], and the ''porteño'' neighbourhoods of [[Flores]], [[Villa Soldati]], [[Villa Lugano]] and [[Pompeya]].<ref name="bolivian settlement in gba" /> Unfortunately, many Amerindian or Mestizo people of Bolivian/Paraguayan/Peruvian origin have suffered either of [[racist discrimination]] and violence<ref>[http://www.pagina12.com.ar/2001/01-06/01-06-02/pag17.htm «A witness narrates how a Bolivian woman was thrown off a train: Tale of a Journey to Xenophobia (Spanish)»] by Cristian Alarcón. Diario ''Página/12'', 2 June 2001.</ref><ref>[http://www.pagina12.com.ar/diario/sociedad/3-102111-2008-04-09.html «A bullet loaded with racist hatred (Spanish)»], Diario ''Página/12'', 9 April 2008.</ref> or have been victims of [[sexual slavery]]<ref>[http://www.perfilcristiano.com/trata-de-personas-en-argentina/ Human Trafficking in Argentina (Spanish).]</ref> and [[forced labor]] in textile [[sweat shops]].<ref>[http://edant.clarin.com/diario/2000/07/05/o-02002.htm Forced Labor in Argentina (Spanish)] Diario ''Clarín'', 5 July 2000.</ref> | ||

{{Image|Natalia Oreiro.jpg|right| | {{Image|Natalia Oreiro.jpg|right|160px|[[Natalia Oreiro]] is a White Uruguayan actress/singer of [[Galician people|Galician]], [[Italian people|Italian]] and [[French people|French]] descent. She resides in Argentina since 1993, and married [[Divididos]]' guitarist Ricardo Mollo.}} | ||

Nevertheless, generalizations must not be made; some White immigrants from Bolivia, Perú and Paraguay have entered Argentina. Among the Paraguayan immigrants, for example, there have been many of [[German people|German]] and [[Slavic peoples|Slavic]] descent, with surnames like Hoffmann, Schneider or Surnyak. Another example is well-known actor [[Arnaldo André]], who migrated in the 1970s and has developed a long successful career in Argentina. | Nevertheless, generalizations must not be made; some White immigrants from Bolivia, Perú and Paraguay have entered Argentina. Among the Paraguayan immigrants, for example, there have been many of [[German people|German]] and [[Slavic peoples|Slavic]] descent, with surnames like Hoffmann, Schneider or Surnyak. Another example is well-known actor [[Arnaldo André]], who migrated in the 1970s and has developed a long successful career in Argentina. | ||

| Line 301: | Line 301: | ||

''La Oma era rubia y se ve que era una linda alemana.''<br><br>"The Oma is a seventy-something years-old woman;<br>she lives in the Chaco woods, near San Bernardo.<br>She has eyes as blue as the water from the seas,<br>because she came from far away, and the sky got into her blood.[...]<br>The Oma was blonde, and it shows that she was a beautiful German woman."|''Written by Daniel Altamirano and Pedro Favini.''}} | ''La Oma era rubia y se ve que era una linda alemana.''<br><br>"The Oma is a seventy-something years-old woman;<br>she lives in the Chaco woods, near San Bernardo.<br>She has eyes as blue as the water from the seas,<br>because she came from far away, and the sky got into her blood.[...]<br>The Oma was blonde, and it shows that she was a beautiful German woman."|''Written by Daniel Altamirano and Pedro Favini.''}} | ||

[[Image:Soledad Pastorutti.jpg| | [[Image:Soledad Pastorutti.jpg|275px|thumb|right|<small> [[Soledad Pastorutti]] is a young folklore singer born in [[Arequito, Santa Fe]] of Italian descent; she was part of a new "folklore boom" in the 1990s. One of her major hits is ''A Don Ata'', a [[chacarera]] written by Mario Álvarez Quiroga paying homage to [[Atahualpa Yupanqui]].</small>]] | ||

Other native rhythms -like [[chacarera]] and [[Zamba (artform)|zamba]]- were not so heavily influenced by the immigrants, but they began to be played with other European instruments; one example is [[Sixto Palavecino]]'s use of the violin to play the chacarera. Regardless of the origin of the different rhythms and styles, European immigrants and their descendants rapidly assimilated the local music as their own, and contributed to those genres creating new songs. | Other native rhythms -like [[chacarera]] and [[Zamba (artform)|zamba]]- were not so heavily influenced by the immigrants, but they began to be played with other European instruments; one example is [[Sixto Palavecino]]'s use of the violin to play the chacarera. Regardless of the origin of the different rhythms and styles, European immigrants and their descendants rapidly assimilated the local music as their own, and contributed to those genres creating new songs. | ||

| Line 321: | Line 321: | ||

The first rock and roll songs -sung in [[Spanish language|Spanish]]- that were heard in Argentina were ''[[La Bamba (song)|La Bamba]]'' (sung by Chicano artist [[Ritchie Valens]]) and translated cover versions performed by Mexican bands such as Los Teen Tops and Los Blue Caps of songs originally sung by [[Bill Haley]], [[Elvis Presley]], [[Chuck Berry]], [[Buddy Holly]] and [[Jerry Lee Lewis]]. Some of these songs became classics in Spanish; for example ''La Plaga'' (''[[Good Golly, Miss Molly]]'', by [[Little Richard]]) and ''Popotitos'' (''Bony Moronie'', by [[Larry Williams]]). The first Argentine rock band was formed in 1956; they were Mr. Roll & the Rockers, led by Eddie Pequenino (featuring [[Lalo Schifrin]] as piano player). In the early 1960s many rock classics of the 1950s were performed locally by Los Red Caps -a fictional band led by [[Palito Ortega|Ramón "Palito" Ortega]] for the TV program ''El Club del Clan''- and [[Sandro|Sandro & Los de Fuego]]. Notwithstanding, by the late 1960s the local musicians were ready to stop copying [[American rock]], and create original songs in Spanish to express their own feelings. | The first rock and roll songs -sung in [[Spanish language|Spanish]]- that were heard in Argentina were ''[[La Bamba (song)|La Bamba]]'' (sung by Chicano artist [[Ritchie Valens]]) and translated cover versions performed by Mexican bands such as Los Teen Tops and Los Blue Caps of songs originally sung by [[Bill Haley]], [[Elvis Presley]], [[Chuck Berry]], [[Buddy Holly]] and [[Jerry Lee Lewis]]. Some of these songs became classics in Spanish; for example ''La Plaga'' (''[[Good Golly, Miss Molly]]'', by [[Little Richard]]) and ''Popotitos'' (''Bony Moronie'', by [[Larry Williams]]). The first Argentine rock band was formed in 1956; they were Mr. Roll & the Rockers, led by Eddie Pequenino (featuring [[Lalo Schifrin]] as piano player). In the early 1960s many rock classics of the 1950s were performed locally by Los Red Caps -a fictional band led by [[Palito Ortega|Ramón "Palito" Ortega]] for the TV program ''El Club del Clan''- and [[Sandro|Sandro & Los de Fuego]]. Notwithstanding, by the late 1960s the local musicians were ready to stop copying [[American rock]], and create original songs in Spanish to express their own feelings. | ||

{{Image|León Gieco 1980.jpg|right| | {{Image|León Gieco 1980.jpg|right|160px|[[León Gieco]] is a well-known singer-songwriter of Italian descent, born in [[Cañada Rosquín|Cañada Rosquín, Santa Fe]]. His major hit is ''Sólo le pido a Dios''.}} | ||

The single ''La balsa / Ayer nomás'' -recorded in 1967 by [[Los Gatos (band)|Los Gatos]], a band from [[Rosario, Santa Fe]]- is considered the first single disc of genuine rock "made in Argentina".<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap2.html La historia del rock. Chapter 2. (Spanish)]</ref> Los Gatos, [[Almendra (band)|Almendra]] (formed by [[Luis Alberto Spinetta]], [[Edelmiro Molinari]], Rodolfo García and Emilio Del Guercio), [[Manal]] ([[Javier Martínez (musician)|Javier Martínez]], [[Claudio Gabis]] -of Ashkenazi descent- and Alejandro Medina) and [[Vox Dei]] (Ricardo Soulé -of French descent-, Willy Quiroga, Juan Carlos Godoy and Rubén Basoalto) are considered the pioneer bands of Argentine rock. Los Gatos played mostly [[beat music]], [[Almendra (band)|Almendra]] had a mixed style of rock/pop/instrumental music, [[Manal]]'s sound had a strong influence of [[blues-rock]] and [[Vox Dei]] was the first exponent of Argentina's [[hard-rock]]. | The single ''La balsa / Ayer nomás'' -recorded in 1967 by [[Los Gatos (band)|Los Gatos]], a band from [[Rosario, Santa Fe]]- is considered the first single disc of genuine rock "made in Argentina".<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap2.html La historia del rock. Chapter 2. (Spanish)]</ref> Los Gatos, [[Almendra (band)|Almendra]] (formed by [[Luis Alberto Spinetta]], [[Edelmiro Molinari]], Rodolfo García and Emilio Del Guercio), [[Manal]] ([[Javier Martínez (musician)|Javier Martínez]], [[Claudio Gabis]] -of Ashkenazi descent- and Alejandro Medina) and [[Vox Dei]] (Ricardo Soulé -of French descent-, Willy Quiroga, Juan Carlos Godoy and Rubén Basoalto) are considered the pioneer bands of Argentine rock. Los Gatos played mostly [[beat music]], [[Almendra (band)|Almendra]] had a mixed style of rock/pop/instrumental music, [[Manal]]'s sound had a strong influence of [[blues-rock]] and [[Vox Dei]] was the first exponent of Argentina's [[hard-rock]]. | ||

| Line 327: | Line 327: | ||

In the early 1970s, the duet [[Sui Generis]] -[[Charly García]] and [[Nito Mestre]]- entered the musical scene with an acoustic/folk sound, and gained a massive audience among teenagers. After their break-up in [[1975]], their folk style was continued by two other duets: [[Pastoral (folk band)|Pastoral]] -Alejandro DeMichele and Miguel Erausquin- and [[Vivencia]].<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap4.html La historia del rock. Chapter 4 (Spanish)]</ref> Band [[Arco Iris]] (led by [[Academy Award|Oscar]] winner [[Gustavo Santaolalla]]) also reached popularity with their hit single ''Mañanas campestres'' in [[1972]]. Almendra bisdanded in 1971, so Spinetta created [[Pescado Rabioso]], with a strong rock/blues sound; among its members there was a young [[David Lebón]] (of [[Ashkenazi]] descent). In the mid-seventies, Argentine rock was heavily influence by British [[symphonic rock]], so new bands such as Luis Spinetta's [[Invisible (band)|Invisible]], Edelmiro Molinari's [[Color Humano]], [[Charly García]]'s [[La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros]], [[Crucis (band)|Crucis]] and [[ALAS (band)|ALAS]] appeared. But their music was not a mere copy of the foreign rock; for example, in Invisible's album ''El Jardín de los Presentes'' ([[1976]]) and its track ''Las golondrinas de Plaza de Mayo'', Spinetta and his partners combined the symphonic rock with [[Tango music|tango]], creating the tango-rock. A similar case is Alas' album ''Pinta tu Aldea'' ([[1977]]) and the song ''La caza del mosquito'', written by Gustavo Moretto. Charly García also made fusions with folklore music; for example, Sui Generis' song ''Cuando comenzamos a nacer'', has an intro with reminiscence of [[Andean music]]. Other Argentines of European descent that stood out in the 1970s were [[León Gieco]] (who wrote his pacifist hymn ''Solo le Pido a Dios'' in 1978) with his folk-rock style, and [[Pappo|Norberto "Pappo" Napolitano]] with his blues-rock band [[Pappo's Blues]]. | In the early 1970s, the duet [[Sui Generis]] -[[Charly García]] and [[Nito Mestre]]- entered the musical scene with an acoustic/folk sound, and gained a massive audience among teenagers. After their break-up in [[1975]], their folk style was continued by two other duets: [[Pastoral (folk band)|Pastoral]] -Alejandro DeMichele and Miguel Erausquin- and [[Vivencia]].<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap4.html La historia del rock. Chapter 4 (Spanish)]</ref> Band [[Arco Iris]] (led by [[Academy Award|Oscar]] winner [[Gustavo Santaolalla]]) also reached popularity with their hit single ''Mañanas campestres'' in [[1972]]. Almendra bisdanded in 1971, so Spinetta created [[Pescado Rabioso]], with a strong rock/blues sound; among its members there was a young [[David Lebón]] (of [[Ashkenazi]] descent). In the mid-seventies, Argentine rock was heavily influence by British [[symphonic rock]], so new bands such as Luis Spinetta's [[Invisible (band)|Invisible]], Edelmiro Molinari's [[Color Humano]], [[Charly García]]'s [[La Máquina de Hacer Pájaros]], [[Crucis (band)|Crucis]] and [[ALAS (band)|ALAS]] appeared. But their music was not a mere copy of the foreign rock; for example, in Invisible's album ''El Jardín de los Presentes'' ([[1976]]) and its track ''Las golondrinas de Plaza de Mayo'', Spinetta and his partners combined the symphonic rock with [[Tango music|tango]], creating the tango-rock. A similar case is Alas' album ''Pinta tu Aldea'' ([[1977]]) and the song ''La caza del mosquito'', written by Gustavo Moretto. Charly García also made fusions with folklore music; for example, Sui Generis' song ''Cuando comenzamos a nacer'', has an intro with reminiscence of [[Andean music]]. Other Argentines of European descent that stood out in the 1970s were [[León Gieco]] (who wrote his pacifist hymn ''Solo le Pido a Dios'' in 1978) with his folk-rock style, and [[Pappo|Norberto "Pappo" Napolitano]] with his blues-rock band [[Pappo's Blues]]. | ||

{{Image|Fito Paez 2.jpg|left| | {{Image|Fito Paez 2.jpg|left|160px|[[Fito Páez]] is a very prolific singer-songwriter of Spanish descent, born in [[Rosario, Santa Fe]]. His major hits include ''Giros'', ''Y dale alegría a mi corazón'', and ''El amor después del amor''.}} | ||

In 1982, when the Argentine Armed Forces recovered the [[Falkland Islands|Falkland/Malvinas Islands]], and [[Falklands/Malvinas War|the war with Great Britain]] began, the [[Proceso de Reorganización Nacional|military dictatorship]] forbid the broadcasting of music in [[English language|English]]; so the radios had to airplay more Argentine rock than ever before.<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap21.html La historia del rock. Chapter 21 (Spanish)]</ref> This caused that many new solo artist had much more space to be heard: [[Alejandro Lerner]], [[Sandra Mihanovich]], [[Celeste Carballo]], [[Raúl Porchetto]], etc. [[Serú Girán]] -the band formed by Charly García in 1978 (with David Lebón, [[Pedro Aznar]] and [[Oscar Moro]])- also reached the top of its popularity in 1982 with the live album ''No Llores por Mí, Argentina''. | In 1982, when the Argentine Armed Forces recovered the [[Falkland Islands|Falkland/Malvinas Islands]], and [[Falklands/Malvinas War|the war with Great Britain]] began, the [[Proceso de Reorganización Nacional|military dictatorship]] forbid the broadcasting of music in [[English language|English]]; so the radios had to airplay more Argentine rock than ever before.<ref>[http://www.lahistoriadelrock.com.ar/gen/cap21.html La historia del rock. Chapter 21 (Spanish)]</ref> This caused that many new solo artist had much more space to be heard: [[Alejandro Lerner]], [[Sandra Mihanovich]], [[Celeste Carballo]], [[Raúl Porchetto]], etc. [[Serú Girán]] -the band formed by Charly García in 1978 (with David Lebón, [[Pedro Aznar]] and [[Oscar Moro]])- also reached the top of its popularity in 1982 with the live album ''No Llores por Mí, Argentina''. | ||

| Line 350: | Line 350: | ||

====Pop/Romantic Music==== | ====Pop/Romantic Music==== | ||

{{Image|Raval por siempre.JPG|right| | {{Image|Raval por siempre.JPG|right|160px|[[Estela Raval]] -Palma Ravallo- is a famous singer of bolero and [[doo wop]] songs, born in a family of [[Italia|Italian immigrants]].}} | ||

The [[bolero]] was a genre of romantic music that first appeared in [[Cuba]], and it spread to all Latin America during the 1950s and 1960s. Although most songwriters and performers of the genre are [[Cuban people|Cuban]] or Mexican, Argentina contributed to bolero with some singers and songwriters such as [[Chico Novarro]] (of Ashkenazi descent), Mario Clavel, Danni Martin, Leo Marini, [[María Martha Serra Lima]], [[Estela Raval]] -his parents were Italian- and Roberto Yanés. | The [[bolero]] was a genre of romantic music that first appeared in [[Cuba]], and it spread to all Latin America during the 1950s and 1960s. Although most songwriters and performers of the genre are [[Cuban people|Cuban]] or Mexican, Argentina contributed to bolero with some singers and songwriters such as [[Chico Novarro]] (of Ashkenazi descent), Mario Clavel, Danni Martin, Leo Marini, [[María Martha Serra Lima]], [[Estela Raval]] -his parents were Italian- and Roberto Yanés. | ||

| Line 356: | Line 356: | ||

Pop ballad is connected to bolero in the sense that it is another type of romantic music; it is spread worldwide in most cultures and languages, so it does not need much introduction. Many Argentine artists have performed both boleros and ballads as well, including those mentioned in the previous paragraph. Among the White Argentines who have written and/or performed ballads throughout their careers we may mention: [[Sergio Denis]] (of Volga German descent), [[Sandro|Roberto Sánchez "Sandro"]], [[Alberto Cortez]] (his father was Spanish), [[César Pueyrredón]], Tormenta, etc. | Pop ballad is connected to bolero in the sense that it is another type of romantic music; it is spread worldwide in most cultures and languages, so it does not need much introduction. Many Argentine artists have performed both boleros and ballads as well, including those mentioned in the previous paragraph. Among the White Argentines who have written and/or performed ballads throughout their careers we may mention: [[Sergio Denis]] (of Volga German descent), [[Sandro|Roberto Sánchez "Sandro"]], [[Alberto Cortez]] (his father was Spanish), [[César Pueyrredón]], Tormenta, etc. | ||

{{Image|Axel.jpg|left| | {{Image|Axel.jpg|left|160px|[[Axel (singer)|Axel Fernando]] is another pop singer-songwriter, with [[Flemish]] ancestry, born in Rafael Calzada, [[Greater Buenos Aires]].}} | ||

Besides, some artists who started their careers in the rock scene -such as [[Alejandro Lerner]], [[Sandra Mihanovich]] (of Ashkenazi and Croatian descent, respectively) and [[Patricia Sosa]]- have turned their styles into ballad later. | Besides, some artists who started their careers in the rock scene -such as [[Alejandro Lerner]], [[Sandra Mihanovich]] (of Ashkenazi and Croatian descent, respectively) and [[Patricia Sosa]]- have turned their styles into ballad later. | ||

Revision as of 13:04, 9 June 2011

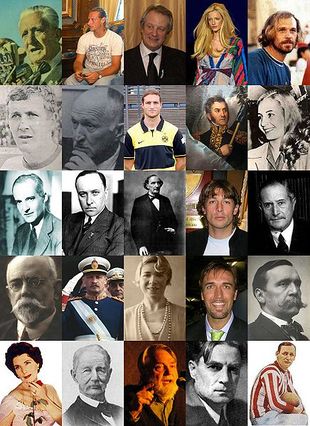

2nd row: Carlos Babington • Deolindo Bittel • Diego Klimowicz

José de San Martín • Eva Perón

3rd row: Luis Federico Leloir • Richard Walther Darré • Bartolomé Mitre • Gabriel Heinze • Carlos Ibarguren

4th row: Francisco Moreno • Juan Carlos Onganía • Alfonsina Storni • Gabriel Batistuta • Carlos Pellegrini

5th row: Libertad Lamarque • Hermann Burmeister • Osvaldo Bayer • Roberto Arlt • Jorge Brown

White Argentines are the Argentine people of predominantly European/Middle Eastern descent. They are descendants of colonists from Spain and Portugal during the colonial period prior to 1810, and mainly of immigrants from Europe and the Middle East in the great immigratory wave during the late 19th century and early 20th century.[1][2][3] Although no official census data exist, some international sources claim that they make up 85.8%,[4] 89.7%[5] or 97%[6] of Argentina's population.

Usage of the term

White Argentine -or White Argentinian- is an umbrella term including various distinct ethnicities (colectividades in Spanish) -including Italian Argentines, Spanish-Argentines, French Argentines, Irish Argentines, German Argentines, Arab Argentines, and many others- as well as the mixture among them. This term is most frequently used in English language sources[7] [8]. Its direct equivalent in Spanish language, "argentino blanco", appears in some Argentine bibliography,[9] but it is not currently used in Argentina neither as a legal/official term, nor in common speech.

Another equivalent in Spanish might be "Criollo", but that term was originally restricted to the unmixed descendants of Spaniards, born in the Americas. Given the great diversity of ethnic origins of the European immigrants of the 19th and 20th centuries in Argentina, "Criollo" might not be the most accurate term. Nevertheless, the term is sometimes used by some Spanish-speaking authors as synonym for White Latin American, regardless of the European ethnicity of origin.[10] Besides, in Argentina the meaning of Criollo was intentionally changed during the years ot the great immigratory wave -making it ambiguous- so it might include all the Argentina-born individuals, regardless of race, as opposed to all the European/Middle Eastern newcomers and their children, who were collectively nicknamed Gringos.[11]

Some definitions of this term include Jewish (both Ashkenazi and Sephardic) and Arab people, coming from Europe and the Middle East. Although these groups are sometimes considered non-White, in Argentina they are frequently classified as "whites" for their resemblance of other European Mediterranean peoples, and in opposition to all the Amerindian, Mestizo, Black/Mulatto and East Asian ethnic groups. The same happens in the rest of the Americas; for example, the US Census Bureau defines White people as "having origins in any of the original peoples of Europe, the Middle East, or North Africa."

Distribution

White Argentines may live in any part of the country, but their concentration varies according to the region. Due to the fact that the main entrance gate of European immigrants was the port of Buenos Aires, they settled especially in the central-eastern region called Pampas (the provinces of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Córdoba, Entre Ríos and La Pampa),[11] and in the southern region called Patagonia (the provinces of Río Negro, Neuquén, Chubut, Santa Cruz and Tierra del Fuego), for it was populated mainly by people coming from the Pampas. They also reside in important numbers in the central-western region called Cuyo (the provinces of Mendoza, San Juan and San Luis) and the north-eastern region called Litoral (the provinces of Corrientes, Misiones, Chaco and Formosa).

They are also found in the major cities of the north-western provinces of Salta, Jujuy, Tucumán, Catamarca, La Rioja and Santiago del Estero, but they are nearly non-existent in the rural areas. Their presence in this region is lesser due to several reasons: it was the most densely populated region of the country (mainly by Amerindian and Mestizo people) until the immigratory wave of 1857-1940, and it was the area where the European newcomers settled the least.[11] During the last decades, due to internal migration from these northern provinces, and due to immigration especially from Bolivia, Perú and Paraguay (which have Amerindian and Mestizo majorities[12][13][14]), the percentage of White Argentines in certain areas of the Greater Buenos Aires, and the provinces of Salta and Jujuy has significantly decreased as well.[15]

Estimates

As it was explained in the introduction of this article, no official census data exist on the precise amount or percentage of White Argentines today; this is because Argentina's National Institute of Statistics and Censuses (INDEC) does not conduct ethnic/racial censuses, nor includes questions about ethnicity. The National Census conducted on 27 October 2010 only included questions on Indigenous peoples -completing the survey performed in 2005- and on Afro-descendants.[17]

Nevertheless, most international sources agree in their claim that White Argentines make up at least 85% of Argentina's population. Worldstatesmen.org -an on-line encyclopedia- estimates an 89.7% (86.4% White/European plus 3.3% Arab),[5] and the World Fact File powered by Dorling Kindersley Books also claims an 85% (83% Indo-European, plus 2% Jewish).[18] Other on-line encyclopedias also display similar percentages.[19]

The Joshua Project -that provides information on ethnic people groups around the world, with missionary purposes- states that White Argentines and other whites (Europeans and Middle-Easterners) in Argentina comprise 85.8% [4] of the total population. This percentage does not show explicitly, but after doing some mathematics, the results are as follows: Argentinians White -the resulting ethnic group out of the melting pot of immigration in Argentina- sum up 29,031,000 or 72.3% of the population. The other European/Caucasus ethnic groups and Uruguayans White sum up 4,258,500 (10.6%), and Arabs sum 1,173,100 more (2.9%). All together, Whites in Argentina would comprise 34,462,600 or 85,8% out of a total population of 40,133,230.

The work Ethnic Groups Worldwide: A Ready Reference Handbook, written by David Levinson, also provides an estimate of 85% of people of European origins in Argentina.[20]

Another work titled Composición Étnica de las Tres Áreas Culturales del Continente Americano al Comienzo del Siglo XXI, which is a very complete and detailed study on the ethnic composition of Ibero-America written by Mexican UAEM scholar Francisco Lizcano Fernández, also estimates a White population of 87.8% in Argentina, or about 32,551,000 people. This figure comprises 85% Criollos (the term he uses for Whites) plus 2.8% Arabs, that he classifies as "Asians".[10]

The figure of 97%[6] given by the CIA Factbook seems to be exaggerated; either it counts both White and Mestizo population all together,[20] or it is the result of the successful campaign implemented by Argentina's ruling elite in the early 20th century to present the country as much White as possible.[11] It is frequently consulted and used as source for many news articles.[21]

History

Colonial and post-independence period

The presence of White people in what is now Argentina began in 1516, when Spanish Adelantado Juan Díaz de Solís explored the Río de la Plata and named it "Mar Dulce" (Sweet Sea). In 1527, explorer Sebastián Gaboto founded the fort of Sancti Spiritus, near Coronda, Santa Fe; this was the first Spanish settlement on Argentine soil. The process of Spanish occupation continued with expeditions coming from Upper Peru (now Bolivia), that founded Santiago del Estero in 1553, and the cities of San Miguel de Tucumán (1565) and Córdoba (1573) later on. Taking Asunción as an operative base, other Spanish expeditions founded the cities of Buenos Aires (1580) and Corrientes (1588).

Although the estimates vary, it is a fact that Spanish immigration from the peninsula towards the New World was scanty during all the colonial period. Some estimates state that less than 200,000 Spaniards arrived in the Americas during the period 1509-1790.[22] On the other hand, Peter Muschamp Boyd-Bowman -an Emeritus Professor of Spanish Linguistics- estimated that about 437,669 Spaniards went and established in the American possessions between 1506 and 1650; of this total, a figure between 10,500 and 13,125 Peninsulares settled in the Río de la Plata region during the 18th century.[23]

It was not until the creation of the Viceroyalty of Río de la Plata in 1776, that the first censuses with classification into castas were conducted. The 1778 Census ordered by viceroy Juan José de Vértiz in Buenos Aires revealed that, of a total population of 37,130 inhabitants (including both city and surrounding countryside), the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 25,451, or 68.55% of the total. Another census carried out in the Corregimiento de Cuyo in 1777 showed that the Spaniards and Criollos numbered 4,491 (or 51.24%) out of a population of 8,765 inhabitants. In Córdoba (city and countryside) the Spanish/Criollo people comprised a 39.36% (about 14,170) of 36,000 inhabitants.[24]

Nevertheless, these censuses were generally restricted to the cities and the surrounding rural areas, so little is known about the racial composition of large areas of the Viceroyalty -as the Litoral, for example- though it is supposed that Spaniards and Criollos were always a minority, with the other castas comprising the majority. It is worth noting that, since a person who was classified as Peninsular or Criollo had access to more privileges in the colonial society, many Castizos (or "White Mestizos") purchased their limpieza de sangre (purity of blood). This passing was common during the colonial period, so some of the figures shown above may include Castizos that "passed" as White.[24]

Although being a minority in demographics terms, the Criollo people played a leading role in the independentist movement that started in 1810 and led to the independence of Argentina from Spain in 1816. Argentine national heroes such as Manuel Belgrano and José de San Martín, military men as Cornelio Saavedra, José Rondeau, Carlos María de Alvear and Miguel de Azcuénaga, and politicians as Juan José Paso, Mariano Moreno, Juan José Castelli, and Gervasio Posadas were mostly Criollos of Spanish, Italian or French descent; some Spaniards also collaborated with the movement, as Domingo Matheu and Juan Larrea. Nevertheless, the war effort fell on the Mestizo, Mulatto and Black populations, who composed most of the troops during the wars of independence, and so they suffered heavy losses of lives, as they were frequently used as "cannon fodder".

In 1822, Bernardino Rivadavia -then Minister of Government of Buenos Aires Province- ordered Ventura Arzac to conduct a new Census in the city, and it showed these results: the city had then 55,416 inhabitants, of which 40,000 were White (about 72.2%). Of this total of Whites, a 90% were Criollos, a 5% were Spaniards, and the other 5% were from other European nations.[26]

After the wars for independence, a long period of fierce internal struggle followed. During the period 1826-1852, the fight was mainly between Federalist (those who supported the provinces' autonomy) and Unitarian caudillos (who supported a centralized government). After the fall of Juan Manuel de Rosas in 1852, and until 1861, the conflict was between Buenos Aires Province Autonomists and the Argentine Confederation Federal government. Once again, the leading men involved in the fight were almost entirely Criollos of Spanish descent, and the troops were mostly Mestizo and Mulatto people. Among those Criollos leaders were: Juan Manuel de Rosas, Ángel Pacheco, Facundo Quiroga, Juan Lavalle, Gregorio Aráoz de Lamadrid, Pedro Ferré, Justo José de Urquiza, Bartolomé Mitre, Santiago Derqui, etc. During that period some Europeans settled in the country as well -sometimes hired by the local governments. Notable among them, Saboyan litographist Charles H. Pellegrini (President Carlos Pellegrini's father) and his wife Maria Bevans, Napolitan journalist Pedro de Angelis, and German physician/zoologist Hermann Burmeister.

An estimate by José Ingenieros states that in 1826 the Argentine territory was populated by 630,000 people, of whom only 13,000 were White; if this figure were correct, Whites comprised a mere 1.66% of the total.[27] According to historian John W. White's estimate, those percentages had barely changed by 1852; out of a total 785,000 inhabitants, a 22,000 were White -a 2,8%- divided in 15,000 Criollos and 7,000 Europeans.[28]

Because of the long civil conflict, there were neither economical resources nor political stability to carry out any census until the 1850s, when some provincial censuses were organized. Anyway, these censuses did not continued with the classification into castas typical of the pre-independence period. The first post-independence census conducted in Buenos Aires took place in 1855; it showed that there were 26,149 European inhabitants in the city. Among the nationals there is no distinction of race, but it does distinguish literates from illiterates; by that time formal education was a privilege almost exclusive for the upper sectors of society, who were predominantly White. If both groups of European residents and the 21,253 Argentine literates are summed, it might be estimated that about 47,402 White people resided in Buenos Aires in 1855; they would comprised about 51,58% of a total population of 91,895 inhabitants.[29]

The great immigratory wave from Europe (1857-1940)

In February 1856, the municipal government of Baradero granted lands for the settlement of ten Swiss families in an agricultural colony near that town. Later that year, another colony was founded by Swiss immigrants in Esperanza, Santa Fe. In spite of these isolated provincial initiatives, it was not until the Argentine Confederation and the Buenos Aires Province definitively unified in 1862 -and a strong central government could be established- that Presidents Bartolomé Mitre, Domingo Sarmiento and Nicolás Avellaneda implemented policies that encouraged massive European immigration. In 1876, during Avellaneda's presidential period, the Congress voted and sanctioned the new Law 817 of Immigration and Colonization. During the following decades, and until the mid-twentieth century, waves of European settlers came to Argentina. Major contributors included Italy (initially from Piedmont, Veneto and Lombardy, later from Campania, Calabria, and Sicily),[30] and Spain (most were Galicians and Basques, but there were Asturians, Cantabrians, Catalans, and Andalusians).

Smaller but significant numbers of immigrants include Germans, primarily Volga Germans from Russia, but also Germans from Germany, Switzerland, and Austria; French which mainly came from the Occitania region of France; Slavic groups which most were Croats and Poles, but there also were Ukrainians, Belarusians, Russians, Bulgarians, Serbs and Montenegrins; British came mainly from England and Wales: Irish who were escaping from the Potato famine or British rule; Scandinavians from Sweden, Denmark, Finland, and Norway. Smaller waves of settlers from Australia and South Africa, and the United States can be traced in Argentine immigration records.

From the former Ottoman Empire came mainly Greeks, Armenians and Arabs (from what is now Lebanon and Syria). They entered the country with Turkish passport, so they were colloquially nicknamed "turcos". The majority of Argentina's Jewish community derives from immigrants of north and eastern European origin (Ashkenazi Jews), and about 15–20% from Sephardic groups from Syria. Argentina is home to the fifth largest Ashkenazi Jewish community in the world. (See also History of the Jews in Argentina).

This migratory influx had mainly two effects on Argentina's demography:

1) The exponential growth of the country's population. In the first National Census of 1869 the Argentine population was just 1,877,490 inhabitants, in 1895 it had doubled up to 4,044,911, in 1914 it had reached 7,903,662, and by 1947 it had doubled again up to 15,893,811. It is estimated that by 1920, more than 50% of the residents in Buenos Aires had been born abroad. According to Zulma Recchini de Lattes' estimate, if this great immigratory wave from Europe and the Middle East had not happened, Argentina's population by 1960 would have been less than 8 millions, while the national census carried out that year revealed an amount of 20,013,793 inhabitants.[31] As it is shown in the chart below, Argentina received a total amount of 6,611,000 European and Middle-Eastern immigrants during the period 1857-1940.[32]

2) A radical change in its ethnic composition; the 1914 National Census revealed that around 80% of the national population were either European immigrants, their children or grandchildren.[33] Among the remaining 20% (those descended from the population residing locally before this immigrant wave took shape), around a third were White. Put down to numbers, this means that about an 86.6% (out of a total population of 7,903,662) or 6,844,000 people residing in Argentina were White.[34]

The distribution of these European/Middle Eastern immigrants was not uniform across the country; most newcomers settled in the coastal cities and the farmlands of Buenos Aires, Santa Fe, Córdoba and Entre Ríos. For example, the 1914 National Census showed that, of almost three million people -2,965,805 to be exact- living in the provinces of Buenos Aires and Santa Fe, 1,019,872 were European immigrants, and one and a half million more were children of European mothers. So Whites comprised at least an 84,9% of the Pampa Gringa, as it was called. But this was not the same situation in the rural areas of the northwestern provinces; there the immigrants (mostly of Syrian-Lebanese origin) represented a mere 2.6% (about 15,600) of a total rural population of 600,000 in Jujuy, Salta, Tucumán, Santiago del Estero and Catamarca.[11][35]

European immigration continued to account for over half the nation's population growth during the 1920s, and was again significant (albeit in a smaller wave) following World War II.[33]

Origin of the immigrants until 1940

Source: Dirección Nacional de Migraciones, National Bureau of Migrations, 1970.

2nd immigratory wave after World War II Mauricio Macri -the Mayor of Buenos Aires City- is the son of businessman Francisco Macri, who was born in Rome and emigrated as a young man in 1949. After the Second World War, many Europeans fled to Argentina, escaping the hunger and poverty of the post-war period. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, during the period 1941-1950 at least 392,603 Europeans entered the country: 252,045 Italians, 110,899 Spaniards, 16,784 Poles, 7,373 Russians and 5,538 French.[37] Among the notable Italian immigrants in that period were protest singer Piero De Benedictis (emigrated with his parents in 1948),[38] actors Rodolfo Ranni (emigrated in 1947)[39] and Gianni Lunadei (1950),[40] César Civita (1941),[41] businessman Francisco Macri (1949),[42] Pablo Verani (1947),[43] and rock musician Kay Galiffi (1950).[44] Argentina also received thousands of Germans who came bankrupt -like Oskar Schindler and his wife, for example- and Ashkenazi Jews. Unfortunately, among those "good" Germans there were hundreds of Nazi war criminals; Adolf Eichmann, Josef Mengele, Erich Priebke, Rodolfo Freude (who became the first director of Argentine State Intelligence), and the Ustaše Head of State of Croatia, Ante Pavelić -among others- entered the country in this period. It is still matter of debate whether the Argentine government of the time was aware of the presence of these criminals on Argentine soil or not; but the consequence was that Argentina was considered a Nazi Haven for several decades.[45] White Argentines, therefore, likely peaked as a percentage of the national population at over 90% on or shortly after the 1947 census. The flow of European immigration continued during the 1950s, but -compared to the previous decade- it is evident that it was diminishing considerably. The Marshall Plan implemented by the United States to help Western Europe recover from the consequences of World War II was working, and emigration was not such a necessity. During the period 1951-1960, only 242,889 Europeans entered Argentina: 142,829 were Italians, 98,801 were Spaniards, 934 were French, and 325 were Poles. The next decade (1961–1970), the total amount of European immigrants barely reached 13,363 (9,514 Spaniards, 1,845 Poles, 1,266 French and 738 Russians).[37] During the 1970s, the European immigration was nearly non-existent; the internal struggle inside the Peronism (Montoneros versus Triple A) caused terrorism and guerrilla warfare first, and a brutal repression by the Armed Forces followed after 1976 under the name of Proceso de Reorganización Nacional. Such an internal situation encouraged emigration rather than immigration -at least by the Europeans- and this is also evident in the numbers; during the period 1971-1976 at least 9,971 Europeans left the country.[37] During the period 1976-1983 thousands of White Argentines and numerous Europeans were kidnapped and killed in clandestine centers by the grupos de tareas (task groups) of the military dictatorship. Among the White Argentines who were victims of the repression can be mentioned: Haroldo Conti, Dagmar Hagelin, Rodolfo Walsh, Héctor Oesterheld (all presumably assassinated in 1977) and Jacobo Timerman (who was liberated in 1979; he went to exile in Israel, and returned in 1984). In 1983-1984, the CONADEP -a special comission gathered by President Raúl Alfonsín and led by writer Ernesto Sábato- investigated and documented 8,960 cases[48] clarifying that the list was by no means exhaustive; so some other estimates vary between 13,000 and 30,000 missing people. White Latin American immigrantsAs it was mentioned in the Distribution section, since the 1960s until now, the main source of immigration switched from Europe to the bordering South American countries. During the period in between the Censuses of 1895 and 1914, the immigrants from Europe comprised 88.4% of the total, and the Latin American immigrants represented only the 7.5%. By the decade of 1960-1970, this tendency had completely reverted: the Latin American immigrants were the 76.1% and the Europeans merely comprised an 18.7% of the total.[49] Given that the main sources of South American immigrants since the 1960s have been Bolivia, Paraguay and Perú, most of these immigrants have been either Amerindian or Mestizo, for these groups represent the ethnic majorities in their countries of origin.[12][13][14] The increasing numbers of immigrants from these sources has caused the percentage of White Argentines to be reduced significantly in certain areas of the Greater Buenos Aires; mainly in the partidos of Morón, La Matanza, Escobar and 3 de Febrero, and the porteño neighbourhoods of Flores, Villa Soldati, Villa Lugano and Pompeya.[15] Unfortunately, many Amerindian or Mestizo people of Bolivian/Paraguayan/Peruvian origin have suffered either of racist discrimination and violence[50][51] or have been victims of sexual slavery[52] and forced labor in textile sweat shops.[53]  Natalia Oreiro is a White Uruguayan actress/singer of Galician, Italian and French descent. She resides in Argentina since 1993, and married Divididos' guitarist Ricardo Mollo. Nevertheless, generalizations must not be made; some White immigrants from Bolivia, Perú and Paraguay have entered Argentina. Among the Paraguayan immigrants, for example, there have been many of German and Slavic descent, with surnames like Hoffmann, Schneider or Surnyak. Another example is well-known actor Arnaldo André, who migrated in the 1970s and has developed a long successful career in Argentina. Uruguayan immigrants represent a very distinct case, for they may pass unnoticed as "foreigners". Uruguay received a great part of the same immigratory influx that changed Argentina´s ethnic profile, so most Uruguayans are White; estimates of White population in Uruguay oscilate from 87.4%[54] to 94.6%.[55] Besides, Uruguayans and Argentinians speak the same language variety; the Rioplatense Spanish, which is heavily influence by the entonation patterns of the Italian language's southern dialects.[56] Unlike the cases of racist discrimination against Bolivians, Paraguayans and Peruvians, Uruguayans have not suffered any type of racism or xenophobia against them. According to the Uruguayan collectivity, 218,000 Uruguayans migrated to Argentina between 1960 and 1980.[57] The official censuses show a slow growth of Uruguayan immigrants: 51,100 in 1970; 114,108 in 1980 and 135,406 in 1991; but the 2001 National Census shows a lower figure: 117,564.[58] Other source estimates the number of White Uruguayans and their descendants in 725,000.[4] Among the Uruguayan immigrants who have settled, developed their professional career, and have had their children in Argentina, we may find: sports journalist Víctor Hugo Morales, actor/comedian Berugo Carámbula, his daughter María and his son Gabriel Carámbula, actress/singer Natalia Oreiro, actresses China Zorrilla and Adela Gleijer, actors Osvaldo Laport and Juan Manuel Tenuta, among many others. Argentina has also received White people from other Latin American countries, such as Chile and Cuba. Estimates of the White population in Chile greatly vary from 22%[59] or 30%,[60] up to 52.7%[10] or 64%;[61][62] so about half of all Chilean immigrants (212,429 in 2001[58]) and their descendants in Argentina might be White. Among these immigrants, they can be mentioned: Chilean model/DJ Cecilia Amenábar (who was married with Gustavo Cerati and had two children with him), María Ostoić -Néstor Kirchner's mother (born in Punta Arenas in a family of Croatian descent)- and Cuban neurosurgeon Roberto Quiñones (Cuban dissident Hilda Molina's son; he married an Argentine woman and they had two sons[63]). 3rd immigratory wave from Eastern Europe (1994-2000) President Carlos Saúl Menem (1989-1999); his parents were of Syrian descent. He offered the European Union to receive immigration from Eastern Europe in 1992. In 1992, after the fall of the Communist regimes of the Soviet Union and its allies, the governments of Western Europe were worried about a possible massive exodus from Eastern Europe and Russia. President Carlos Saúl Menem -in the political framework of relaciones carnales with the Western World- offered to receive part of that emigratory wave in Argentina. On 19 December 1994, Resolution 4632/94 was enacted, allowing a "special treatment" for all the applicants who wished to emigrate from the republics of the ex-Soviet Union. Summarizing, from January 1994 till December 2000, a total 9,399 Eastern Europeans travelled and settled in Argentina. Of the total, 6,720 were Ukrainians (71.5%), 1,598 were Russians (17%), 160 Romanians (1.7%), 122 Bulgarians (1.3%), 94 Armenians (1%), 150 Georgians/Moldovans/Poles (1,6%) and 555 (5.9%) travelled with Soviet passport.[64] An 85% of the newcomers were under age 45, and 51% had terciary level education, so most of them integrated quite rapidly into Argentine society, although some had to work for lower wages than expected at the beginning.[65] Among them, there were 200 Romanian Gypsy families that arrived in 1998, and 140 more Romanian Gypsies who migrated to Uruguay in 1999, but only to enter Argentina later by crossing the Uruguay river through Fray Bentos, Salto or Colonia.[66] After this wave from Eastern Europe, White/European immigration in Argentina has not stopped either. According to the National Bureau of Migrations, some 14,964 Europeans have settled in Argentina (3,599 Spaniards, 1,407 Italians and 9,958 from other countries)during the period 1999-2004. To this figure, some 8,285 Americans and 4,453 Uruguayans may be partially added, since these countries have White majorities of 75%[67] and 87%[54] in their populations.[68] The Myth of White ArgentinaThis myth was created by Argentina's ruling elite (La Generación de 1880, led by Julio Argentino Roca) during the late 19th century and the early 20th century; it stated that almost all the inhabitants of Argentina were of European origin, i.e. "White". This same period was the time of formation of all the national states in Hispanic America, and the elites of countries like Mexico and Perú chose to create myths of "Mestizo countries" -where there was a harmony between the Spanish and Amerindian cultural and ethnic elements within those societies- implementing policies of "creolization" or assimilation of their Amerindian populations into the Criollo society. Thus, popular education systems were established in the official Spanish language, leaving aside the Amerindian tongues. Education was also an instrument to spread criollo culture, trying to erradicate some "undesirable" indigenous habits, customs, festivities, etc.[11] A similar process took place in Argentina, but this time the country's ruling elite chose to create the myth of a "White country" instead. By that moment the great immigratory wave from Europe was really changing the ethnic profile of Argentina -at least in the Pampas, the most populated region- so it was not difficult to present the country as "White" so as to promote European investments, mainly by British companies. Besides, to manipulate the percentages of White people, racial categories were wiped out from the censuses questionnaires, leaving only national categories, thus leading to the undercounting of Mestizos and Afro-Argentines. Furthermore, the meaning of the word Criollo was intentionally changed during those years -making it ambiguous- so it might include all the Argentina-born individuals, regardless of race, so they could also be counted as White, and inflate the percentages. In the short and long runs, the propaganda campaign organized by the Generación de 1880 was very successful, for even nowadays two important reference books in English language, the CIA Factbook and the Columbia Encyclopedia, display figures of 97%-98% White people living in Argentina.[6][11] The myth also percoladed into Argentina's self-image in its own educational system. Well into the 1980s, many textbooks used in the secondary schools showed figures of 99% White people in Argentina, and only 1% Amerindians.[69] All these comments on this myth do not intend to imply that it is a complete lie at all; on the contrary. The myth of a White Argentina is nowadays partially false in degree, but it has proved to be true in essence. The percentage of 97% Whites in Argentina was probably never true; but it is a fact that White people nowadays comprise a majority of the country's population. As it was shown in the Estimates section, all international sources agree in figures around 85%.[5][18][4][10] [20]

Influence on Argentine cultureAs for all Latin America, many cultural products in Argentina are the result of a fusion of European, Amerindian and Black African elements. Nevertheless, the impact of European immigration on both Argentina's culture and demography has been so deep and extensive, that their culture has become mainstream and it is shared by the rest of Argentines, so it is not perceived as a separate "White" culture. Even those traditional elements that have Amerindian origin -as the mate and the Andean music- or Criollo origin -the asado, the empanadas, and some genres within folklore music- were rapidly adopted, assimilated and sometimes modified by the European immigrants and their descendants, and so they were given a "European flavor".[33][7][70] This is a review of the main Criollo/European contributions to Argentine culture; and also a review of the most prominent Argentinians of European/Middle Eastern descent in every field of culture in Argentina. The lists of notable White Argentines may include some people who are European by birth, but they are considered Argentines because they immigrated during their childhood/youth, and developed their careers and died in Argentina. MusicTango Carlos Gardel (1890-1935) is the most famous singer-songwriter of classical tango; he was -reportedly- French by birth.[71] Argentine tango is a hybrid genre, result of the fusion of different ethnic and cultural elements, so well intermingled that it is difficult to identify them separately. According to some experts, tango has combined elements from three main sources: 1) The music played by the Black African communities of the Río de la Plata region. Its very name might derive from a word in Yoruba -a Bantu language- and its rhythm appears to be based on candombe.[72] 2) The milonga campera, a popular genre among the gauchos that lived in the Buenos Aires countryside, and later moved to the city looking for better jobs. 3) The music brought by the European immigrants: the Andalucian tanguillo, the polka, the waltz and the tarantella.[73] They heavily influenced its melody and its sound by adding instruments such as piano, violin and -especially- bandoneón.  Ástor Piazzolla (1921-1992) was one of the finest bandoneonists ever; his parents were Italian immigrants from Trani, Apulia.[74] In spite of this tripartite origin, tango mainly developed as a urban music, and it was assimilated and embraced by the European immigrants and their descendants; most icons of the genre were either European or had European ancestry. Among the tango pioneers of the early 20th century we find Juan de Dios Filiberto (his grandparents were from Genova), Juan Maglio, Eduardo Arolas (his parents were French), Enrique Delfino and Roberto Firpo. Carlos Gardel, the greatest exponent of classical tango in the 1930s, was -reportedly- born in France, and his songwriting partner Alfredo Le Pera had Calabrian ancestry. Any list of important singers, composers, and arrangers of the Golden Age of tango -in the 1940s and 1950s- shows a collection of Italian and French surnames: Enrique Santos Discepolo (his father was an Italian musician), Homero Manzi, Pascual Contursi, Sebastián Piana, Enrique Cadícamo, Raúl Garello, Julio De Caro (both his parents were Italian), Osvaldo Fresedo, Ignacio Corsini (born in Sicily), Enrique Francini, Agustín Magaldi and Armando Pontier. The most prestigious orchestra directors were of Italian descent: Aníbal Troilo, Carlos Di Sarli (his father was Italian), Juan D'Arienzo and Osvaldo Pugliese. Singer Alberto Castillo -known for his song Al compás del tamboril- was actually surnamed De Lucca. Juan Carlos Cobián, another prestigious composer and orchestra director, had his father born in Spain.  Adriana Varela is a famous tango singer of Italian descent -her real surname is Lichinchi- born in Avellaneda. The creator of New Tango in the 1960s, bandoneonist and composer Astor Piazzolla, had direct Italian ancestry, and his songwriting partner Horacio Ferrer was of French descent. Other artists of European descent during the 1960s and 1970s were Roberto Goyeneche (with Basque ancestry[75]) and Edmundo Rivero (with Spanish and British descent). Current exponents, such as singer-songwriter Cacho Castaña and singers Susana Rinaldi (nicknamed la Tana) and Adriana Varela also are of Italian descent.

FolkloreWhen the Spaniards arrived in what is now Argentina, the Amerindian inhabitants already had their own musical culture: instruments, dances, rhythms and styles. Much of that culture was lost during and after the conquest; only the music played by the Andean peoples survived in the shape of chants such as vidalas and huaynos, and in dances like the carnavalito. The peoples of Gran Chaco and Patagonia -areas that the Spaniards did not effectively occupied- kept their cultures almost untouched until the late 19th century.  Chango Spasiuk is a prestigious composer and accordion player; his grandparents were Ukrainian immigrants who settled in Misiones.[76] The major Spanish contribution to music in the Río de la Plata area during the colonial period was the introduction of three instruments: the vihuela or guitarra criolla, the bombo legüero and the charango (a small guitar, similar to the tiple used in the Canary Islands; made with the shell of an armadillo). Once the Criollos obtained their independence from Spain, they had the chance to create new musical styles; dances like pericón, triunfo, gato and escondido, and chants like cielito and vidalita all appeared during the post-independence period, especially in the 1820s.[77]

The ethnic change that Argentina was undergoing is also evident in the lyrics of some songs; for example, the creole waltz La pulpera de Santa Lucía refers to a blond-haired, blue-eyed waitress in a pulpería of Buenos Aires countryside.

Another example is the chamamé titled La Oma, that describes a blue-eyed old woman of German origin that lived in the Chaco region; Oma is the German word for "grandmother" or "old woman".

Soledad Pastorutti is a young folklore singer born in Arequito, Santa Fe of Italian descent; she was part of a new "folklore boom" in the 1990s. One of her major hits is A Don Ata, a chacarera written by Mario Álvarez Quiroga paying homage to Atahualpa Yupanqui. Other native rhythms -like chacarera and zamba- were not so heavily influenced by the immigrants, but they began to be played with other European instruments; one example is Sixto Palavecino's use of the violin to play the chacarera. Regardless of the origin of the different rhythms and styles, European immigrants and their descendants rapidly assimilated the local music as their own, and contributed to those genres creating new songs. A list -not exhaustive- of notable White Argentines that have written and/or recorded folklore music includes: Songwriters: Ariel Petrocelli, Artidorio Cresseri, Luis Profili (author of Zamba de mi esperanza), Armando Tejada Gómez, Carlos Guastavino, and songwriting teams such as Ariel Ramírez - Félix Luna and Gustavo Leguizamón - Manuel Castilla. Singer-songwriters: Carlos DiFulvio, Teresa Parodi, Chango Spasiuk (his grandparents emigrated from Ukraine), Chango Nieto, Hernán Figueroa Reyes, César Isella, Facundo Saravia, Eduardo Falú (of Syrian descent), Jorge Rojas, Los Hermanos Ábalos (with Criollo and Italian ancestry). Performers: Soledad Pastorutti, Oscar "Chaqueño" Palavecino (both with Italian ancestry) , Jorge Cafrune (of Arab descent), Antonio Tormo (his parents were from Valencia, Spain), Lucía Ceresani. Besides, many TV hosts of programs specialized on folklore were of Lebanese or Italian ancestry; Julio Mahárbiz, Quique DaPiaggi and Carlos Giachetti. Andean music was much less influenced by Criollo and European culture, so it has remained quite "pure" -except for the use of charango and Spanish language- and it is most frequently written, performed and recorded by Mestizo and Amerindian Argentines.

Rock