Wheat/Citable Version: Difference between revisions

imported>David Tribe |

imported>David Tribe |

||

| Line 55: | Line 55: | ||

* Hexaploid wheats evolved in farmers' fields. Either emmer or durum wheat hybridized with yet another wild diploid grass (''Aegilops tauschii'') to make the [[hexaploid]] (6 chromosomes) wheats, [[spelt]] wheat and [[common wheat|bread wheat]].<ref name=Hancock /> | * Hexaploid wheats evolved in farmers' fields. Either emmer or durum wheat hybridized with yet another wild diploid grass (''Aegilops tauschii'') to make the [[hexaploid]] (6 chromosomes) wheats, [[spelt]] wheat and [[common wheat|bread wheat]].<ref name=Hancock /> | ||

Wild grasses in the genus ''Triticum'' and related genera, and grasses such as rye have been a source of useful traits for cultivated wheat [Transgenic plant|breeding]] since the 1930s. | |||

[[Heterosis]] or hybrid vigor (as in the familiar F1 hybrids of maize) occurs in common (hexaploid) wheat, but it is difficult to produce seed of hybrid cultivars on a commercial scale (as is done with [[maize]]) because wheat flowers are complete and normally [[Self-pollination|self-pollinate]].<ref name=Bajaj>Bajaj, Y. P. S. (1990) ''Wheat''. Springer. pp. 161-63. ISBN 3-540-51809-6.</ref> Commercial hybrid wheat seed has been produced using chemical hybridizing agents, plant growth regulators that selectively interfere with pollen development, or naturally occurring cytoplasmic male sterility systems. Hybrid wheat has been a limited commercially success, in Europe (particularly [[France]]), the USA and South Africa.<ref>Basra, Amarjit S. (1999) ''Heterosis and Hybrid Seed Production in Agronomic Crops''. Haworth Press. pp. 81-82. ISBN 1-56022-876-8.</ref> F1 hybrid wheat cultivars should not be confused with standard method of breeding inbred wheat cultivars by crossing two lines using hand emasculation, then selfing or inbreeding the progeny many (ten or more) generations before release selections are identified to released as a variety or cultivar.<ref name=Bajaj /> | [[Heterosis]] or hybrid vigor (as in the familiar F1 hybrids of maize) occurs in common (hexaploid) wheat, but it is difficult to produce seed of hybrid cultivars on a commercial scale (as is done with [[maize]]) because wheat flowers are complete and normally [[Self-pollination|self-pollinate]].<ref name=Bajaj>Bajaj, Y. P. S. (1990) ''Wheat''. Springer. pp. 161-63. ISBN 3-540-51809-6.</ref> Commercial hybrid wheat seed has been produced using chemical hybridizing agents, plant growth regulators that selectively interfere with pollen development, or naturally occurring cytoplasmic male sterility systems. Hybrid wheat has been a limited commercially success, in Europe (particularly [[France]]), the USA and South Africa.<ref>Basra, Amarjit S. (1999) ''Heterosis and Hybrid Seed Production in Agronomic Crops''. Haworth Press. pp. 81-82. ISBN 1-56022-876-8.</ref> F1 hybrid wheat cultivars should not be confused with standard method of breeding inbred wheat cultivars by crossing two lines using hand emasculation, then selfing or inbreeding the progeny many (ten or more) generations before release selections are identified to released as a variety or cultivar.<ref name=Bajaj /> | ||

[[http://www.k-state.edu/wgrc/Germplasm/synthetics.html Synthetic hexaploids]] made by crossing Aegilops tauschii and various durum wheats are now starting to be used, and these widen the range of genetic diversity in cultivated wheats. | |||

== Hulled versus free-threshing wheat == | == Hulled versus free-threshing wheat == | ||

Revision as of 18:25, 29 December 2006

| Wheat | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

|

T. aestivum |

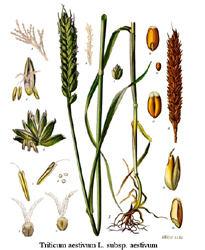

Wheat (Triticum spp.)[1] is a grass that is cultivated worldwide. Globally, it is the most important human food grain and ranks second in total production as a cereal crop behind maize; the third being rice.[2] Wheat grain is a staple food used to make flour for leavened, flat and steamed breads; cookies, cakes, pasta, noodles and couscous;[3] and for fermentation to make beer,[4] alcohol, vodka[5] or biofuel[6]. The husk of the grain, separated when milling white flour, is bran.[7] Wheat is planted to a limited extent as a forage crop for livestock and the straw can be used as fodder for livestock or as a construction material for roofing thatch.[8][9]

History

The first cereal known to have been domesticated, wheat originated in southwest Asia in the area known as the Fertile Crescent. The earliest archaeological evidence for wheat cultivation comes from the Levant, Israel, Syria and Turkey. Around 10,000 years ago,[10] wild einkorn and emmer wheat were domesticated as part of the origins of agriculture in the fertile crescent. Cultivation and repeated harvesting and sowing of the grains of wild grasses led to the selection of mutant forms with tough ears which remained attached to the ear during the harvest process, and larger grains. (Selection for these traits is an important part of crop domestication). Because of the loss of seed dispersal mechanisms, domesticated wheats cannot survive in the wild.[11]

The cultivation of wheat began to spread beyond the Fertile Crescent during the Neolithic period. By 5,000 B.P., wheat had reached Ethiopia, India, Ireland and Spain. A millennium later it reached China.[11] Agricultural cultivation using horse collar leveraged plows (3000 years B.P.) increased cereal grain productivity yields, as did the use of seed drills which replaced broadcasting sowing of seed in the 18th century. Yields of wheat continued to increase, as new land came under cultivation and with improved agricultural husbandry involving the use of fertilizers, threshing machines and reaping machines (the 'combine harvester'), tractor-draw cultivators and planters, and better varieties (see green revolution and Norin 10 wheat). With population growth rates falling, while yields continue to rise, the acreage devoted to wheat may now begin to decline for the first time in modern human history.[12][9]

Genetics and breeding

Wheat genetics is more complicated than that of most other domesticated species. Some wheat species occur as stable polyploids, having more than two sets of diploid chromosomes.[13]

- Most tetraploid wheats (e.g. emmer and durum wheat) are derived from wild emmer, T. dicoccoides. Wild emmer is the result of a hybridization between two diploid wild grasses, T. urartu and a wild goatgrass such as Aegilops searsii or Ae. speltoides. The hybridization that formed wild emmer occurred in the wild, long before domestication.[13]

- Hexaploid wheats evolved in farmers' fields. Either emmer or durum wheat hybridized with yet another wild diploid grass (Aegilops tauschii) to make the hexaploid (6 chromosomes) wheats, spelt wheat and bread wheat.[13]

Wild grasses in the genus Triticum and related genera, and grasses such as rye have been a source of useful traits for cultivated wheat [Transgenic plant|breeding]] since the 1930s.

Heterosis or hybrid vigor (as in the familiar F1 hybrids of maize) occurs in common (hexaploid) wheat, but it is difficult to produce seed of hybrid cultivars on a commercial scale (as is done with maize) because wheat flowers are complete and normally self-pollinate.[14] Commercial hybrid wheat seed has been produced using chemical hybridizing agents, plant growth regulators that selectively interfere with pollen development, or naturally occurring cytoplasmic male sterility systems. Hybrid wheat has been a limited commercially success, in Europe (particularly France), the USA and South Africa.[15] F1 hybrid wheat cultivars should not be confused with standard method of breeding inbred wheat cultivars by crossing two lines using hand emasculation, then selfing or inbreeding the progeny many (ten or more) generations before release selections are identified to released as a variety or cultivar.[14]

[Synthetic hexaploids] made by crossing Aegilops tauschii and various durum wheats are now starting to be used, and these widen the range of genetic diversity in cultivated wheats.

Hulled versus free-threshing wheat

Four wild species of wheat, and in the domesticated einkorn[16], emmer[17] and spelt[18] wheats are hulled (in German, Spelzweizen). This more primitive morphology consists of toughened glumes that tightly enclose the grains, and (in domesticated wheats) a semi-brittle rachis that breaks easily on threshing. The result is that when threshed, the wheat ear breaks up into spikelets. To obtain the grain, further processing, such as milling or pounding, is needed to remove the hulls or husks. In contrast, in free-threshing (or naked) forms such as durum wheat and common wheat, the glumes are fragile and the rachis tough. On threshing, the chaff breaks up, releasing the grains. Hulled wheats are often stored as spikelets because the toughened glumes give good protection against pests of stored grain.[16]

Naming

There are many taxonomic classification systems used for wheat species, discussed in a separate article on Wheat taxonomy. It is good to keep in mind that the name of a wheat species from one information source may not be the name of a wheat species in another.

Major cultivated species of wheat

- Common Wheat or Bread wheat - (T. aestivum) A hexaploid species that is the most widely cultivated in the world.

- Durum - (T. durum) The only tetraploid form of wheat widely used today, and the second most widely cultivated wheat today.

- Einkorn - (T. monococcum) A diploid species with wild and cultivated variants. One of the earliest cultivated, but rarely planted today.

- Emmer - (T. dicoccon) A tetraploid species, cultivated in ancient times but no longer in widespread use.

- Spelt - (T. spelta) Another hexaploid species cultivated in limited quantities.

- Kamut® or QK-77 - (T. polonicum or T. durum) A trademarked tetraploid cultivar grown in small quantities that is extensively marketed. Originally from the Middle East

Within a species, wheat cultivars are further classified by (1) growing season, such as winter wheat vs. spring wheat[9], by (2) gluten content, such as hard wheat (high protein content) vs. soft wheat (high starch content), or by (3) grain color (red, white or amber).

Economics

Harvested wheat grain is classified according to grain properties (see below) for the purposes of the commodities market. Wheat buyers use the classifications to help determine which wheat to purchase as each class has special uses. Wheat producers determine which classes of wheat are the most profitable to cultivate with this system.

Wheat is widely cultivated as a cash crop because it produces a good yield per unit area, grows well in a temperate climate even with a moderately short growing season, and yields a versatile, high-quality flour that is widely used in baking. Most breads are made with wheat flour, including many breads named for the other grains they contain like most rye and oat breads. Many other popular foods are made from wheat flour as well, resulting in a large demand for the grain even in economies with a significant food surplus.

Costs and returns

Low international wheat prices in recent years have often encouraged farmers to shift to more profitable crops. in 1998 at a time when price at harvest per bushel was $2.68 revealed average operating costs of $1.43 per bushel and total costs $3.97 per bushel according to a 2002 USDA report[19].

In that study, farm wheat yields averaged 41.7 bushel an acre, and typical total wheat production value was $31,900 per farm, with total farm production value (including other crops) of $173,681 per farm, plus $17,402 in government payments. There were significant profitability differences between low- and high-cost farms. These profitability differences were mainly due to crop yield differences, location, and farm size.

Production and consumption statistics

In 1997, global per capita wheat consumption was 101 kg, with the highest per capita consumption (623 kg) found in Denmark.

See also International wheat production statistics.

| Top Ten Wheat Producers - 2005 (million metric ton) | |

| China | 96 |

| India | 72 |

| USA | 57 |

| Russia | 46 |

| France | 37 |

| Canada | 26 |

| Australia | 24 |

| Germany | 24 |

| Pakistan | 22 |

| Turkey | 21 |

| World total | 626 |

| Source: UN Food & Agriculture Organisation (FAO) | |

Agronomy

Crop development

While winter wheat lies dormant during a winter freeze, wheat normally requires between 110 and 130 days between planting and harvest, depending upon climate, seed type, and soil conditions.

Crop management decisions require the knowledge of stage of development of the crop. In particular, spring fertilizers applications, herbicides, fungicides, growth regulators are typically applied at specific stages of plant development.

For example, current recommendations often indicate the second application of nitrogen be done when the ear (not visible at this stage) is about 1 cm in size (Z31 on Zadoks scale). Knowledge of stages is also interesting to identify periods of higher risk, in terms of climate. For example, the meïosis stage is extremely susceptible to low temperatures (under 4 °C) or high temperatures (over 25 °C). Farmers also benefit from knowing when the flag leaf (last leaf) appears as this leaf represents about 75% of photosynthesis reactions during the grain filling period and as such should be preserved from disease or insect attacks to ensure a good yield.

Several systems exist to identify crop stages, with the Feekes and Zadoks scales being the most widely used. Each scale is a standard system which describes successive stages reached by the crop during the agricultural season.

Wheat stages

- Wheat at the anthesis stage (face and side view)

|

|

Diseases

There are numerous wheat diseases, and good overviews of these diseases and their management are available [20]. The main agents causing disease are fungi, bacteria and viruses. Plant breeding to develop new disease resistant varieties, and sound crop management practices are important strategies for disease prevention.

The main wheat-disease categories are:

- Seed-Borne Diseases: Seed-borne diseases include seed-borne scab, seed-borne Stagonospora (previously known as Septoria), common bunt (stinking smut), and loose smut. These are managed with fungicides.

- Leaf- and Head- Blight Diseases: Powdery mildew, leaf rust, Septoria tritici leaf blotch, Stagonospora (Septoria) nodorum leaf and glume blotch, and Fusarium head scab.

- Crown and Root Rot Diseases: Two of the more important crown- and root-rot diseases are take-all and Cephalosporium stripe. Both of these diseases are soilborne.

- Virus Diseases: Wheat spindle streak mosaic (yellow mosaic) and barley yellow dwarf are the two most common virus diseases. Control can be achieved by using resistant varieties.

Main article: Wheat diseases

Pests

Wheat is used as a food plant by the larvae of some Lepidoptera species including The Flame, Rustic Shoulder-knot, Setaceous Hebrew Character and Turnip Moth.

Wheat in the United States

Classes used in the United States are[21]

- Hard Red Spring — Hard, brownish, high protein wheat used for bread and hard baked goods. Bread Flour and high gluten flours are commonly made from hard red spring wheat. Hard red spring wheat accounts for about 25 percent of production and is mainly grown in the Northern Plains (North Dakota, Montana, Minnesota, and South Dakota). Hard red spring wheat is valued for high protein levels, which make it suitable for specialty breads and blending with lower protein wheat. It is primarily traded at the Minneapolis Grain Exchange.

- Hard Red Winter — Hard, brownish, mellow high protein wheat used for bread, hard baked goods and as an adjunct in other flours to increase protein in pastry flour for pie crusts. Some brands of unbleached all-purpose flours are commonly made from hard red winter wheat alone. Accounts for about 40 percent of total production and is grown primarily in the Great Plains (Texas north through Montana). It is primarily traded by the Kansas City Board of Trade.

- Durum — Very hard, translucent, light colored grain used to make semolina flour for pasta.

- Hard White — Hard, light colored, opaque, chalky, medium protein wheat planted in dry, temperate areas. Used for bread and brewing

- Soft Red Winter — Soft, low protein wheat used for cakes, pie crusts, biscuits, and muffins. Cake Flour, for example, is made from soft red winter wheat. Amounts to 15-20 percent of total production, is grown mainly in States along the Mississippi River and in the Eastern States. Flour produced from milling soft Read Winter wheat is used in the United States for cakes, cookies, and crackers. It is primarily traded by the Chicago Board of Trade

- Soft White — Soft, light colored, very low protein wheat grown in temperate moist areas. Used for pie crusts and pastry. Pastry flour, for example, is sometimes made from soft white winter wheat.

Hard wheats are harder to process and red wheats may need bleaching. Therefore, soft and white wheats usually command higher prices than hard and red wheats on the commodities market.

The following text is based on the Household Cyclopedia of 1881:

Wheat may be classed under two principal divisions, though each of these admits of several subdivisions. The first is composed of all the varieties of red wheat. The second division comprehends the whole varieties of white wheat, which again may be arranged under two distinct heads, namely, thick-chaffed and thin-chaffed.

Thick-chaffed wheat varieties were the most widely used before 1799, as they generally make the best quality flour, and in dry seasons, equal the yields of thin-chaffed varieties. However, thick-chaffed varieties are particularly susceptible to mildew, while thin-chaffed varieties are quite hardy and in general are more resistant to mildew. Consequently, a widespread outbreak of mildew in 1799 began a gradual decline in the popularity of thick-chaffed varieties.

References

Citations

- ↑ Jump up to: 1.0 1.1 Belderok, Bob & Hans Mesdag & Dingena A. Donner. (2000) Bread-Making Quality of Wheat. Springer. p.3. ISBN 0-7923-6383-3.

- ↑ FAOSTAT database of World Agriculture, 2006

- ↑ Cauvain, Stanley P. & Cauvain P. Cauvain. (2003) Bread Making. CRC Press. p. 540. ISBN 1-85573-553-9.

- ↑ Palmer, John J. (2001) How to Brew. Defenestrative Pub Co. p. 233. ISBN 0-9710579-0-7.

- ↑ Neill, Richard. (2002) Booze: The Drinks Bible for the 21st Century. Octopus Publishing Group - Cassell Illustrated. p. 112. ISBN 1-841-88196-1.

- ↑ Department of Agriculture Appropriations for 1957: Hearings ... 84th Congress. 2d Session. United States. Congress. House. Appropriations. 1956. p. 242.

- ↑ Ojakangas, Beatrice A. (2002) Great Whole Grain Breads. University of Minnesota Press. p. 48. ISBN 0-8166-4150-1.

- ↑ Smith, Albert E. (1995) Handbook of Weed Management Systems. Marcel Dekker. p. 411. ISBN 0-8247-9547-4.

- ↑ Jump up to: 9.0 9.1 9.2 Bridgwater, W. & Beatrice Aldrich. (1966) The Columbia-Viking Desk Encyclopedia. Columbia University. p. 1959.

- ↑ Kingfisher Books. (2004) The Kingfisher History Encyclopedia. Kingfisher Publications. p. 8. ISBN 0-7534-5784-9.

- ↑ Jump up to: 11.0 11.1 Smith, C. Wayne. (1995) Crop Production. John Wiley and Sons. pp. 60-62. ISBN 0-471-07972-3.

- ↑ The Economist, 2005

- ↑ Jump up to: 13.0 13.1 13.2 Hancock, James F. (2004) Plant Evolution and the Origin of Crop Species. CABI Publishing. ISBN 0-85199-685-X.

- ↑ Jump up to: 14.0 14.1 Bajaj, Y. P. S. (1990) Wheat. Springer. pp. 161-63. ISBN 3-540-51809-6.

- ↑ Basra, Amarjit S. (1999) Heterosis and Hybrid Seed Production in Agronomic Crops. Haworth Press. pp. 81-82. ISBN 1-56022-876-8.

- ↑ Jump up to: 16.0 16.1 Potts, D. T. (1996) Mesopotamia Civilization: The Material Foundations Cornell University Press. p. 62. ISBN 0-8014-3339-8.

- ↑ Nevo, Eviatar & A. B. Korol & A. Beiles & T. Fahima. (2002) Evolution of Wild Emmer and Wheat Improvement: Population Genetics, Genetic Resources, and Genome.... Springer. p. 8. ISBN 3-540-41750-8.

- ↑ Vaughan, J. G. & P. A. Judd. (2003) The Oxford Book of Health Foods. Oxford University Press. p. 35. ISBN 0-19-850459-4.

- ↑ Ali, M.B. (2002) Characteristics and production costs of US wheat farms (SB-974-5 ERS, USDA.)

- ↑ Crop Disease Management Bulle tin 631-98. Wheat Diseases.

- ↑ ERS of the USDA Briefing room Wheat

Further reading

- Bonjean, A.P., and W.J. Angus (editors). The World Wheat Book: a history of wheat breeding. Lavoisier Publ., Paris. 1131 pp. (2001). ISBN 2-7430-0402-9.

- Ears of plenty: The story of wheat, The Economist, Dec 24th 2005, pp. 28-30

- Briefing room Wheat, Economic Research Service of the USDA

See also

External links

- NAWG – Web site of the National Association of Wheat Growers

- CIMMYT – Web site of the International Maize and Wheat Improvement Center

- Colin A. Carter, (2001) Current and Future Trends in the Global Wheat Market, CIMMYT/World Bank Overview

- Triticum species at Purdue University

- A Workshop Report on Wheat Genome Sequencing

- Proceedings of the First International Workshop on Hulled Wheats (PDF) July 1995

- Molecular Genetic Maps in Wild Emmer Wheat

- Winter Wheat in the Golden Belt of Kansas by James C. Malin, University of Kansas, 1944