Civil Rights Movement: Difference between revisions

imported>Russell D. Jones (Moved Content from U.S. history) |

imported>Russell D. Jones (corrections) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

The years from 1954 to 1965 are often regarded as the '''Civil Rights Revolution''', or '''[[Civil Rights Movement]]''' in the [[United States]]. | The years from 1954 to 1965 are often regarded as the '''Civil Rights Revolution''', or '''[[Civil Rights Movement]]''' in the [[United States]]. | ||

While most of the political elite in Washington tended to be sympathetic to the Civil Rights cause (if not totally in favor of legislating in | While most of the political elite in Washington tended to be sympathetic to the Civil Rights cause (if not totally in favor of legislating in favor of civil rights), international factors was used as an argument; Americans, however, ignored foreign opinions. | ||

The [[Brown vs. Board of | The ''[[Brown vs. Board of Education]]'' (1954) decision in the US Supreme Court was the culmination of a judicial movement that had been underway for a decade. It had the short-term effect of ending segregated schools in border states and the long-term effect of ending legalized segregation in schools. | ||

Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins, marches, and non-violent protest. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta [[Martin Luther King]] emerged from the [[Montgomery Bus Boycott]] as a leader of the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second-class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC), the [[Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee]] (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the [[Congress of Racial Equality]] (CORE), and the older [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Thoreauean/Gandhian [[Civil Disobedience]] in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters. Meanwhile. a growing black radical movement (such as [[Black Power]] led by [[Stokely Carmichael]] and [[Nation of Islam|Muslims]] advocated by [[Malcolm X]]), and inner city gangs (such as the [[Black Panthers]], divided black support in the movement. By 1966, the tensions inside the black community were ripping apart the civil rights coalition, as the radicals called for the ousting of all whites in leadership positions. | Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins, marches, and non-violent protest. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta [[Martin Luther King]] emerged from the [[Montgomery Bus Boycott]] as a leader of the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second-class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the [[Southern Christian Leadership Conference]] (SCLC), the [[Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee]] (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the [[Congress of Racial Equality]] (CORE), and the older [[National Association for the Advancement of Colored People]] (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Thoreauean/Gandhian [[Civil Disobedience]] in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters. Meanwhile. a growing black radical movement (such as [[Black Power]] led by [[Stokely Carmichael]] and [[Nation of Islam|Muslims]] advocated by [[Malcolm X]]), and inner city gangs (such as the [[Black Panthers]], divided black support in the movement. By 1966, the tensions inside the black community were ripping apart the civil rights coalition, as the radicals called for the ousting of all whites in leadership positions. | ||

Revision as of 22:35, 10 February 2010

The years from 1954 to 1965 are often regarded as the Civil Rights Revolution, or Civil Rights Movement in the United States.

While most of the political elite in Washington tended to be sympathetic to the Civil Rights cause (if not totally in favor of legislating in favor of civil rights), international factors was used as an argument; Americans, however, ignored foreign opinions.

The Brown vs. Board of Education (1954) decision in the US Supreme Court was the culmination of a judicial movement that had been underway for a decade. It had the short-term effect of ending segregated schools in border states and the long-term effect of ending legalized segregation in schools.

Black leaders claimed that their own efforts were more important in causing change, emphasizing activities like bus boycotts, lunch-counter sit-ins, marches, and non-violent protest. A black Baptist minister from Atlanta Martin Luther King emerged from the Montgomery Bus Boycott as a leader of the new movement. Painstaking work by labor unions, civil rights groups, and mainstream churches, aided by popular outrage at the violent techniques used by police in some southern cities fueled a national consensus that segregated and second-class status had to end. Some of the organizations that spearheaded the movement were the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC, or 'Snick'), the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), and the older National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). All were committed to non-violence and Thoreauean/Gandhian Civil Disobedience in the early years, a tactic that was politically essential in order to win public support and to avoid alienating northern voters. Meanwhile. a growing black radical movement (such as Black Power led by Stokely Carmichael and Muslims advocated by Malcolm X), and inner city gangs (such as the Black Panthers, divided black support in the movement. By 1966, the tensions inside the black community were ripping apart the civil rights coalition, as the radicals called for the ousting of all whites in leadership positions.

Among presidents, however, only Lyndon Johnson actively favored the movement. Dwight Eisenhower advocated a policy of new federalism which was a federal "hands-off" policy regarding states' legislative domains. Only when Orville Faubus attempted to use an instrument of the U.S. armed forces, and thereby usurping Eisenhower duties as commander-in-chief, to block a federal court order in the Little Rock incident did Eisenhower act. John Kennedy for most of his administration was chastened by the narrow margin of victory by which he won the 1960 election and so needed the backing of southern Democrats if he were to maintain his hopes of re-election in 1964. Only after the televised brutal crackdown in Birmingham in June 1963 did Kennedy act by sending the Civil Rights Bill to Congress. But this was the limit of his involvement in the Civil Rights movement. His brother, Robert F. Kennedy while U.S. Attorney General, however, was much more proactive in seeking court orders and using U.S. marshals to protect African Americans during the movement.

In 1957, governor Orville Faubus of Arkansas mobilized the National Guard to prevent a court ordered desegregation of Little Rock Public School, a decision overcome by President Eisenhower's decision to to use Federal troops to enforce legality. In the following years, many southern states and legislatures expressed forceful opposition to what was considered Federal tyranny, and some revised their flags to include the old Confederate banner. In 1962, the prospect of a black student being admitted to the University of Mississippi resulted in lengthy campus riots suppressed by Federal troops and a national guard now brought under Federal control.

Vigilante and terrorist groups formed, such as the reborn Ku Klux Klan. Many individual acts of mobbing and violence towards blacks was common. In 1963, organizer Medgar Evers was assassinated in Mississippi, and four children were killed in the bombing of a black church in Birmingham, Alabama. The following year the Freedom Summer campaign was accompanied by many attacks and murders, which drew worldwide condemnation and the disgust of northerners.

The Civil Rights movement reached its peak between 1963 and 1965. In 1963 the symbolic focus shifted once again to Birmingham, Alabama, which saw concentrated mass protest against segregation laws. The protest turned ugly that May, when police used brutal violence against protesters. This event was shocking in its own right, but was also one of the first times that television cameras broadcast these images to the rest of the world within hours. The images of southern police turning dogs and water-cannon on black children sparked even more international outrage which completely smashed the US's image in the rest of the world as a defender of democracy and Liberty in the face of communist tyranny.

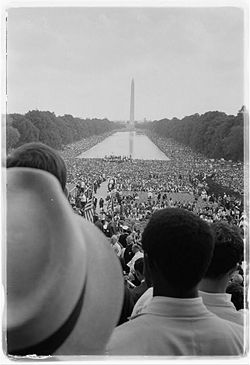

August 1963 brought a mass march in Washington, at which King delivered his famous 'I have a Dream' speech. The aim of this march was to pressure Congress to move on Kennedy's Civil Rights bill. Following Kennedy's assassination, Lyndon Johnson took up the pressure to move the legislation along. It was passed as the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and it prohibited any racial segregation in public facilities and prohibited discrimination employment on the basis of religion, creed, race, or ethnic origin.

Regarding voting rights, black voters in Alabama and Mississippi were widely excluded from the vote by various non-racial voter tests and poll taxes, and only a federal law could permit blacks to secure their gains by a long-term restructuring of the political system. Once again, the measure was obtained in direct response to southern repression, this time with 'Bloody Sunday' at Selma, Alabama which happened in March. By August 1965 the United States passed the Federal voting rights act, the consequences of which would reshape Southern politics. With millions of blacks now enfranchised, President Johnson also recognized he was giving away the Democratic 'Solid South' to pass to the Republican Party for at least a generation.