Chester W. Nimitz: Difference between revisions

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz |

imported>Howard C. Berkowitz No edit summary |

||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{subpages}} | {{subpages}} | ||

{{TOC|right}} | {{TOC|right}} | ||

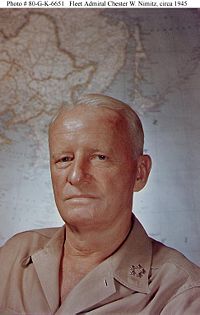

[[Image:Chester Nimitz.jpg|left|200px|Nimitz at Guam, 1945]] | |||

'''Chester William Nimitz''' (1885-1955) rose to the highest rank in the [[United States Navy]], [[fleet admiral]], although as a high school student, he had hoped for an Army career and went to the [[United States Naval Academy]] only when he could not get an appointment to the [[United States Military Academy]] at West Point. Graduating seventh of 114 in the Class of 1905, he went on to a career not only distinguished in the U.S. Navy, but that many historians rate as the greatest, or among the greatest, of fleet-level commanders. | '''Chester William Nimitz''' (1885-1955) rose to the highest rank in the [[United States Navy]], [[fleet admiral]], although as a high school student, he had hoped for an Army career and went to the [[United States Naval Academy]] only when he could not get an appointment to the [[United States Military Academy]] at West Point. Graduating seventh of 114 in the Class of 1905, he went on to a career not only distinguished in the U.S. Navy, but that many historians rate as the greatest, or among the greatest, of fleet-level commanders. | ||

Revision as of 22:53, 17 July 2009

Chester William Nimitz (1885-1955) rose to the highest rank in the United States Navy, fleet admiral, although as a high school student, he had hoped for an Army career and went to the United States Naval Academy only when he could not get an appointment to the United States Military Academy at West Point. Graduating seventh of 114 in the Class of 1905, he went on to a career not only distinguished in the U.S. Navy, but that many historians rate as the greatest, or among the greatest, of fleet-level commanders.

His most noted assignment was as Commander in Chief, Pacific Ocean and Pacific Ocean Areas in World War II, somewhat equivalent to today's United States Pacific Command. Nimitz shared command of the theater with Douglas MacArthur, who headed the Southwest Pacific Area. As opposed to MacArthur's towering ego and imperious manner, Nimitz was a relaxed man who inspired loyalty. When he relieved Admiral Husband Kimmel, who was fired as the commander at the Battle of Pearl Harbor, Nimitz made a point of keeping Kimmel's staff and making only gradual changes, rather than seeking blame.

It has been wryly suggested that he had two enemies, the Japanese and MacArthur. Nimitz chose a less glorious command style than his rough Japanese counterpart, Adm. Isoroku Yamamoto, staying on shore, with full radio communications, than at sea with the fleet. His ability to direct operations without the need for radio silence was a strategic advantage; Yamamoto, for example, was not able to keep situational awareness at the Battle of Midway.

Early career

At Annapolis, the yearbook described him as a man "of cheerful yesterdays and confident tomorrows." Shortly after being commissioned an ensign, which, as opposed to the commission at Academy graduation today, required sea duty, he became an especially young destroyer commander. In 1907, however, he ran the USS Decatur aground, normally a career-ending event.[1]

Returning to the US, he qualified in submarines, received a Silver Lifesaving Medal for rescuing a crewman washed overboard from his boat, and moved into command of the Atlantic Submarine Flotilla in 1912. In 1913, he worked on building the diesel engines for the tanker USS Maumee, and then sent to Germany and Belgium to study diesel design, which remained a specialty throughout his career. In WWI, he was assigned as Chief of Staff to the commander of US submarines in the Atlantic, ADM S. S Robinson.

In September 1918 he came ashore to duty in the office of the Chief of Naval Operations and was a member of the Board of Submarine Design. His first sea duty in big ships came in 1919 when he had one year's duty as Executive Officer of the battleship USS South Carolina. After that, he was assigned to Pearl Harbor where he directed building of the submarine base, and then commanded Submarine Division 14 (COMSUBDIV Fourteen).

In 1922 he was assigned as a student at the Naval War College. While there, he developed a basic Pacific Fleet war plan that formed the basis for operations in WWII. After graduation, he returned to work with Adm. Robinson, then Commander of Battle Forces, and then Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. Commander Battle Forces and later Commander in Chief, U.S. Fleet. During that time, he introduced the circular cruising formation to the fleet, first based on a battleship and then on the early aircraft carrier, USS Langley, in 1924. [2]

For the new Reserve Officers Training Program program, he became, in 1926. he became the first Professor of Naval Science and Tactics for the Unit at the University of California at Berkeley. Throughout the remainder of his life he retained a close association with the University.

Nimitz returned to sea duty, commanding a submarine division, and then a support ship. His first major surface command, in 1933, was the heavy cruiser USS Augusta, flagship of the Asiatic Fleet.

His next shore duty, in 1935, was Assistant Chief of the Bureau of Navigation, a traditional name for the Navy office in charge of personnel. During his time there, he came to the notice of Franklin D. Roosevelt.

Promoted to rear admiral, he commanded a cruiser division and then a battleship division, returning to the Bureau of Navigation in 1939.

Second World War

He took command at Pearl Harbor on 20 December 1941, being sworn in on the deck of the submarine USS Grayling (SS-209). That deck was symbolic of his identification, first and foremost, as a submariner — and being one of the few undamaged vessels left in Pearl.

Beyond the morale-building effect of retaining staff, he immediately pointed out positives, such as the US aircraft carriers and submarine base being undamaged.

Taking the offensive

On 1 February 1942, the first offensive action taken by the U.S. Navy was a carrier air strike on Japanese facilities in the Marshall Islands, especially the Kwajalein group; Kwajalein was the main Japanese base in the region. [3]

Far earlier than expected, he took the offensive to the Japanese in the Doolittle Raid, the Battle of the Coral Sea, and, in what is generally believed to be the turning point of the Pacific war, the Battle of Midway.

In June 1942, he was personally involved in the intelligence preparation for the high-risk Midway operation,[4] as well as concentrating forces for the battle, including patching together the aircraft carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5), damaged in the Battle of the Coral Sea. The naval base had estimated three months of repairs, but she was turned around in three days — sinking at the battle, but a key part of smashing the Japanese carrier fleet.

Accelerating in 1943

Operation FLINTLOCK was the main campaign against the Marshall Islands. Bombardment began in December 1943, and the attacks began, principally against Kwajalein and surrounding islands, in January. The priorities, in 1943, Mille, Maloelap, and Wotje in the Ratak chain, and in the Ralik chain, Jaluit, Kwajalein, and Eniwetok. Jaluit was a seaplane base, all of the other Ratak sites were airfields, and the Ralik locations were anchorages for naval ships. [5] Kwajalein was taken faster than had been expected, and it was under control by February.

He accelerated Operation CATCHPOLE, the invasion of Eniwetok, had been scheduled for May, but the operation was accelerated to mid-February. [6]

Beginning of the end

As the war progressed, he moved his operational headquarters to Guam in January 1945. Winning the Battle of Saipan in June-July 1944, followed by the fall of Prime Minister GEN Hideki Tojo's government, had created a peace faction in the Imperial Japanese Navy.

On 19 December 1944, he was advanced to the newly created rank of fleet admiral.

The end

On 2 September 1945, was the United States signatory to the surrender terms aboard the battleship USS Missouri (BB-62) in Tokyo Bay.

Postwar military

He hauled down his flag at Pearl Harbor on 26 November 1945, and on 15 December relieved Fleet Admiral Ernest King as Chief of Naval Operations for a term of two years. The unquestionably abrasive King had wanted Nimitz to replace him, but the new Secretary of the Navy, James Forrestal, despised King and did not want a potential protege. Nimitz, somewhat hurt by the controversy, insisted, but accepted a compromise two-year appointment. Forrestal found Nimitz to have a very different personality than King, but the damage was done.[7]

On 1 January 1948, he reported as Special Assistant to the Secretary of the Navy in the Western Sea Frontier.

After retirement

In March of 1949, he was nominated as Plebiscite Administrator for Kashmir under the United Nations. When that did not materialize he asked to be relieved and accepted an assignment as a roving goodwill ambassador of the United nations, to explain to the public the major issues confronting the U.N. In 1951, President Truman appointed him as Chairman of the nine-man commission on International Security and Industrial Rights. This commission never got underway because Congress never passed appropriate legislation.[1]

He was a regent of the University of California and did much to restore goodwill with Japan by raising funds to restore the battleship IJN Mikasa, Admiral Heihachiro Togo's flagship at the Battle of Tsushima Strait in 1905.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Fleet Admiral Chester William Nimitz, Naval Historical Center, U.S. Navy

- ↑ E. B. Potter, Nimitz, U.S. Naval Institute, pp. 139-142

- ↑ Commanding Officer, USS Enterprise (CV-6) (7 February 1942), Report of action on February 1, 1942 (Zone Minus Twelve) against Marshall Island Group

- ↑ Layton, Edwin T.; Roger Pineau & John Costello (1985), And I Was There, William Morris

- ↑ , PART III: The Marshalls: Quickening the Pace; Chapter 1 FLINTLOCK Plans and Preparations GETTING ON WITH THE WAR, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in the Second World War, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center Branch, pp. 117-119

- ↑ , PART III: The Marshalls: Quickening the Pace; Chapter 5: The CATCHPOLE Operation CATCHPOLE AND THE LESSER MARSHALLS, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in the Second World War, U.S. Marine Corps Historical Center Branch, pp. 117-119

- ↑ Michael T. Isenberg (1993), Shield of the Republic: The United States Navy in an Era of Cold War and Violent Peace, vol. Volume I, 1945-1962, St. Martin's Press, ISBN 0312099118, pp. 84-85

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- CZ Live

- History Workgroup

- Military Workgroup

- Pacific War Subgroup

- United States Navy Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- History Content

- Military Content

- History tag

- Military tag

- Pacific War tag

- United States Navy tag