Amine gas treating: Difference between revisions

imported>Milton Beychok m (Revised 2 capital letters to 2 lower case letters) |

imported>D. Matt Innis m (Amine gas treating moved to Amine gas treating/Draft: approved) |

Revision as of 22:01, 12 May 2008

Amine gas treating refers to a group of processes that use aqueous solutions of various amines to remove hydrogen sulfide (H2S) and carbon dioxide (CO2) from gases.[1][2] It is a common process unit used in petroleum refineries, petrochemical plants, natural gas processing plants and other industries. The process is also known as acid gas removal and gas sweetening.

Processes within petroleum refineries or natural gas processing plants that remove hydrogen sulfide and/or mercaptans are commonly referred to as sweetening processes because they result in products which no longer have the sour, foul odors of mercaptans and hydrogen sulfide.

There are many different amines used in gas treating:

- Monoethanolamine (MEA)

- Diethanolamine (DEA)

- Methyldiethanolamine (MDEA)

- Diisopropylamine (DIPA)

- Diglycolamine (DGA)

The most commonly used amines in industrial plants are the alkanolamines MEA, DEA, and MDEA.

Amines are also used in many petroleum refineries to remove sour gases from liquid hydrocarbons such as liquified petroleum gas (LPG).

Description of a typical amine treater

Gases containing H2S or both H2S and CO2 are commonly referred to as sour gases or acid gases in the hydrocarbon processing industries. The chemistry involved in the amine treating of such gases varies somewhat with the particular amine being used. For one of the more common amines, methanolamine (MEA) denoted as , the chemistry may be simply expressed as:

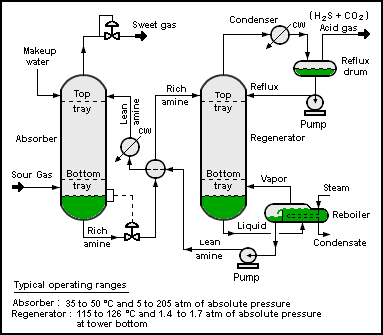

A typical amine gas treating process (as shown in the flow diagram below) includes an absorber unit and a regenerator unit as well as accessory equipment. In the absorber, the downflowing amine solution absorbs H2S and CO2 from the upflowing sour gas to produce a sweetened gas stream (i.e., an H2S-free gas) as a product and an amine solution rich in the absorbed acid gases.

The resultant rich amine is then routed into the regenerator (a distillation column called a stripper with a reboiler) to produce regenerated or lean amine that is recycled for reuse in the absorber. The stripped overhead gas from the regenerator is concentrated H2S and CO2. In petroleum refineries, that stripped gas is mostly H2S, much of which often comes from a sulfur-removing process called hydrodesulfurization. This H2S-rich stripped gas stream is then usually routed into a Claus process to convert it into elemental sulfur. In fact, the vast majority of the 64,000,000 metric tons of sulfur produced worldwide in 2005 was byproduct sulfur from petroleum refineries, natural gas processing plants and other hydrocarbon processing plants. [3][4] In some plants, more than one amine absorber unit may share a common regenerator unit.

In the steam reforming of hydrocarbons (such as natural gas or naphtha) to produce gaseous hydrogen for subsequent use in the industrial synthesis of ammonia, amine treating is one of the commonly used processes for removing excess by-product carbon dioxide in the final purification of the gaseous hydrogen.

New amine-based materials for gas processing

In recent years, interest in the development of new materials and technologies for the capture of carbon dioxide (CO2) has increased significantly. This development appears to be driven largely by increasing concerns about the impact of rising CO2 emissions on climate change. One outcome has been the introduction of new reactive amines which have chemical structures in which the CO2-reactive part of the molecule (the amine group) is tethered to an ionic (salt-like) structural element. The ionic nature of these hybrids makes them less likely to be lost to evaporation during CO2 capture operations, and as a result it may be possible to suppress the typical amine loss in scrubbing systems of about four pounds of amine per ton of CO2 captured. While systems involving the use of certain simple amine-salt solutions in water were first evaluated for CO2 capture decades ago, it was only in 2002 [5] that systems of pure, CO2-reactive liquid salts (amine-appended task-specific ionic liquids called TSILs) were first introduced. Recently, the researchers responsible for that development have reported improved approaches[6] (e.g., the use of Click chemistry and commodity chemicals) for the preparation of CO2-reactive salts, procedures which result in salts that are much less expensive to prepare than the earlier first-generation of materials. Interestingly, the library of new compounds obtained in this fashion also included CO2-reactive salts that are plastic-, resin- and gel-like in character.

References

- ↑ Arthur Kohl and Richard Nielson (1997). Gas Purification, 5th Edition. Gulf Publishing. ISBN 0-88415-220-0.

- ↑ Gary, J.H. and Handwerk, G.E. (1984). Petroleum Refining Technology and Economics, 2nd Edition. Marcel Dekker, Inc. ISBN 0-8247-7150-8.

- ↑ Sulfur production report by the United States Geological Survey

- ↑ Discussion of recovered byproduct sulfur

- ↑ Bates, E. D.; Mayton, R. D.; Ntai, I.; Davis, J. H., Jr., CO2 Capture by a Task-Specific Ionic Liquid, Journal of the American Chemical Society, 2002, Vol. 124, No. 6, 926-927

- ↑ Soutullo, M. D.; Odom, C. I.; Wicker, B. F.; Henderson, C. N.; Stenson, A. C.; Davis, J. H., Jr., Reversible CO2 Capture by Unexpected Plastic-, Resin, and Gel-like Ionic Soft Materials Discovered During the Combi-Click Generation of a TSIL Library, Chemistry of Materials, 2007, Vol. 19, No. 15, 3581-3583

- Pages using ISBN magic links

- Editable Main Articles with Citable Versions

- CZ Live

- Engineering Workgroup

- Chemistry Workgroup

- Chemical Engineering Subgroup

- Articles written in American English

- Advanced Articles written in American English

- All Content

- Engineering Content

- Chemistry Content

- Chemical Engineering tag