Semantic primes: Difference between revisions

imported>Anthony.Sebastian |

imported>Anthony.Sebastian (clarifying) |

||

| Line 2: | Line 2: | ||

:::''See also [[Linguistic universals]]'' | :::''See also [[Linguistic universals]]'' | ||

Suppose you, as a bright child, have an excellent dictionary of the English language — ''The New Oxford American Dictionary'' or ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', say — and you try to use it to learn the 'meaning' of all the words therein, because you lack confidence that you use in a meaningful way all the words you ordinarily use, and because you want to learn the meanings of all the words your elders speak. In your dictionary you will find every entry-word defined in terms of other words, of course. In your determination to learn the meaning (or meanings) of every word in the dictionary, you find you need look up definitions of the words employed in the definitions of every word. But sooner or later you will find that you cannot complete your task — learning the meaning of every word in the dictionary — because every word’s description of meaning employs other entry-words whose meaning you also wish to firmly establish in your mind. You find you have embarked on a circular task, not surprisingly, because the dictionary contains only a closed set of words, finite in number, that enable descriptions of the meanings of each other. If you do not already have in your mind a set of basic words whose meanings you somehow happen to have come to know independently of words — even though you came to associate that set of basic words with their meanings by listening to your elders speaking them — you will remain forever in a continuous circular loop in your dictionary, and fail to achieve your goal. | Suppose you, as a bright child, have an excellent dictionary of the English language — ''The New Oxford American Dictionary'' or ''The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language'', say — and you try to use it to learn the 'meaning' of all the words therein, because you lack confidence that you use in a meaningful way all the words you ordinarily use, and because you want to learn the meanings of all the other words your elders speak. In your dictionary you will find every entry-word defined in terms of other words, of course. In your determination to learn the meaning (or meanings) of every word in the dictionary, you find you need look up definitions of the words employed in the definitions of every word. But sooner or later you will find that you cannot complete your task — learning the meaning of every word in the dictionary — because every word’s description of meaning employs other entry-words whose meaning you also wish to firmly establish in your mind. You find you have embarked on a circular task, not surprisingly, because the dictionary contains only a closed set of words, finite in number, that enable descriptions of the meanings of each other. | ||

If you do not already have in your mind a set of basic words whose meanings you somehow happen to have come to know independently, without the need of words to define them — even though you came to associate that set of basic words with their meanings by listening to your elders speaking them — you will remain forever in a continuous circular loop in your dictionary, and fail to achieve your goal. | |||

If you read linguist Anna Wierzbicka’s book, ''Semantics: Primes and Universals'' (Wierzbicka, 1996), you will find an argument, grounded in biologically plausible hypotheses and experimental observations, suggesting that we all in fact ''do'' have as part of our inherited human faculties a basic set of innate 'concepts', or perhaps more precisely, a non-conscious propensity and eagerness to acquire those concepts and encode them in sound-forms (words). The words that those concepts become encoded in Wierzbicka calls '''semantic primes''', or alternatively, semantic primitives — 'semantic' because linguists have assigned that word in reference to the meaning of words (=linguistic symbols). Words that qualify as semantic primes need no definition in terms of other words. In that sense, they remain undefinable. We know their meaning without having to define them. They allow us to construct other words defined ''by'' them. | If you read linguist Anna Wierzbicka’s book, ''Semantics: Primes and Universals'' (Wierzbicka, 1996), you will find an argument, grounded in biologically plausible hypotheses and experimental observations, suggesting that we all in fact ''do'' have as part of our inherited human faculties a basic set of innate 'concepts', or perhaps more precisely, a non-conscious propensity and eagerness to acquire those concepts and encode them in sound-forms (words). The words that those concepts become encoded in Wierzbicka calls '''semantic primes''', or alternatively, semantic primitives — 'semantic' because linguists have assigned that word in reference to the meaning of words (=linguistic symbols). Words that qualify as semantic primes need no definition in terms of other words. In that sense, they remain undefinable. We know their meaning without having to define them. They allow us to construct other words defined ''by'' them. | ||

Moreover, as we shall learn later, as modern human beings who share the same set of types of inherited determinants (i.e., the human [[Genome|genome]]), all our natural languages, despite the diversity of language families, share the same basic set of innate concepts, or share the same propensity and eagerness to encode the same set of concepts in words. Our common grandmother and grandfather many generations removed may have encoded those concepts in a specific vocabulary, and therefore had an original set of semantic primes. The dispersal of their descendants from their African homeland throughout the world enabled the evolution of many different languages, each with a unique set of sound-forms for their words. Nevertheless the same set of semantic primes remained within each language, though expressed in differing sound-forms. Thus, as Wierzbicka argues, all modern humans have the same set of semantic primes, though not the same set of sound-forms expressing them, rendering semantic primes cross-culturally universal. | Moreover, as we shall learn later, as modern human beings who share the same set of types of inherited determinants that make us human (i.e., the human [[Genome|genome]]), all our natural languages, despite the diversity of language families, share the same basic set of innate concepts, or share the same propensity and eagerness to encode the same set of concepts in words. Our common grandmother and grandfather many generations removed may have encoded those concepts in a specific vocabulary, and therefore had an original set of semantic primes. The dispersal of their descendants from their African homeland throughout the world enabled the evolution of many different languages, each with a unique set of sound-forms for their words. Nevertheless the same set of semantic primes remained within each language, though expressed in differing sound-forms. Thus, as Wierzbicka argues, all modern humans have the same set of semantic primes, though not the same set of sound-forms expressing them, rendering semantic primes cross-culturally universal. | ||

In this article we will elaborate on Wierzbicka’s theory (Wierzbicka, 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka (eds.), 1994); exemplify the list of semantic primes; show how they underlie the meaning of the non-primes in our language; give some of the experimental observations that support the claim of semantic primes as universal among human languages; discuss the contributions and comments of other linguists and scholars from other disciplines; and indicate how far back we can trace the history the idea of semantic primes by any other name. | In this article we will elaborate on Wierzbicka’s theory (Wierzbicka, 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka (eds.), 1994); exemplify the list of semantic primes; show how they underlie the meaning of the non-primes in our language; give some of the experimental observations that support the claim of semantic primes as universal among human languages; discuss the contributions and comments of other linguists and scholars from other disciplines; and indicate how far back we can trace the history the idea of semantic primes by any other name. | ||

Revision as of 17:02, 19 January 2008

- See also Linguistic universals

Suppose you, as a bright child, have an excellent dictionary of the English language — The New Oxford American Dictionary or The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language, say — and you try to use it to learn the 'meaning' of all the words therein, because you lack confidence that you use in a meaningful way all the words you ordinarily use, and because you want to learn the meanings of all the other words your elders speak. In your dictionary you will find every entry-word defined in terms of other words, of course. In your determination to learn the meaning (or meanings) of every word in the dictionary, you find you need look up definitions of the words employed in the definitions of every word. But sooner or later you will find that you cannot complete your task — learning the meaning of every word in the dictionary — because every word’s description of meaning employs other entry-words whose meaning you also wish to firmly establish in your mind. You find you have embarked on a circular task, not surprisingly, because the dictionary contains only a closed set of words, finite in number, that enable descriptions of the meanings of each other.

If you do not already have in your mind a set of basic words whose meanings you somehow happen to have come to know independently, without the need of words to define them — even though you came to associate that set of basic words with their meanings by listening to your elders speaking them — you will remain forever in a continuous circular loop in your dictionary, and fail to achieve your goal.

If you read linguist Anna Wierzbicka’s book, Semantics: Primes and Universals (Wierzbicka, 1996), you will find an argument, grounded in biologically plausible hypotheses and experimental observations, suggesting that we all in fact do have as part of our inherited human faculties a basic set of innate 'concepts', or perhaps more precisely, a non-conscious propensity and eagerness to acquire those concepts and encode them in sound-forms (words). The words that those concepts become encoded in Wierzbicka calls semantic primes, or alternatively, semantic primitives — 'semantic' because linguists have assigned that word in reference to the meaning of words (=linguistic symbols). Words that qualify as semantic primes need no definition in terms of other words. In that sense, they remain undefinable. We know their meaning without having to define them. They allow us to construct other words defined by them.

Moreover, as we shall learn later, as modern human beings who share the same set of types of inherited determinants that make us human (i.e., the human genome), all our natural languages, despite the diversity of language families, share the same basic set of innate concepts, or share the same propensity and eagerness to encode the same set of concepts in words. Our common grandmother and grandfather many generations removed may have encoded those concepts in a specific vocabulary, and therefore had an original set of semantic primes. The dispersal of their descendants from their African homeland throughout the world enabled the evolution of many different languages, each with a unique set of sound-forms for their words. Nevertheless the same set of semantic primes remained within each language, though expressed in differing sound-forms. Thus, as Wierzbicka argues, all modern humans have the same set of semantic primes, though not the same set of sound-forms expressing them, rendering semantic primes cross-culturally universal.

In this article we will elaborate on Wierzbicka’s theory (Wierzbicka, 1996; Goddard and Wierzbicka (eds.), 1994); exemplify the list of semantic primes; show how they underlie the meaning of the non-primes in our language; give some of the experimental observations that support the claim of semantic primes as universal among human languages; discuss the contributions and comments of other linguists and scholars from other disciplines; and indicate how far back we can trace the history the idea of semantic primes by any other name.

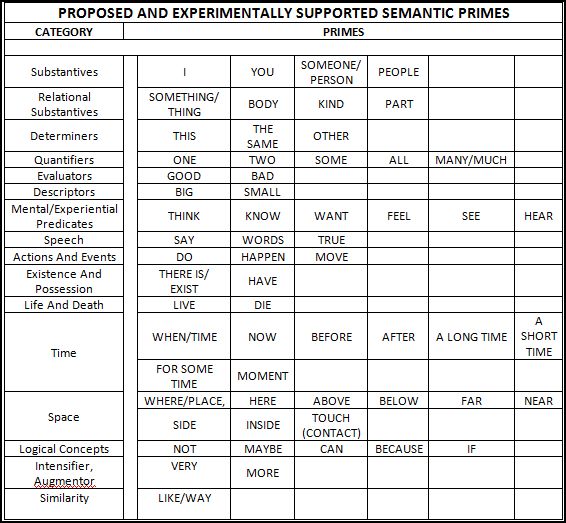

List of semantic primes

Consider Wierzbicka’s colleague, Cliff Goddard's words:

When Wierzbicka and colleagues claim that DO, BECAUSE, and GOOD, for example, are semantic primes, the claim is that the meanings of these words are essential for explicating the meanings of numerous other words and grammatical constructions, and that they cannot themselves be explicated in a non-circular fashion. The same applies to other examples of semantic primes such as: I, YOU, SOMEONE, SOMETHING, THIS, HAPPEN, MOVE, KNOW, THINK, WANT, SAY, WHERE, WHEN, NOT, MAYBE, LIKE, KIND OF, PART OF. Notice that all these terms identify simple and intuitively intelligible meanings which are grounded in ordinary linguistic experience (Goddard, 2002).

ALL PEOPLE KNOW ALL WORDS BELOW:[1]

Notes

- ↑ A sentence using only semantic primes.

References cited

- Goddard C, Wierzbicka A. (eds.) (1994) Semantic and Lexical Universals: Theory and Empirical Findings. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. Publisher’s website’s description of book, with Table of Contents

- Goddard, C. (2002) The search for the shared semantic core of all languages. In Cliff Goddard and Anna Wierzbicka (eds). Meaning and Universal Grammar - Theory and Empirical Findings. Volume I. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 5-40.

- Wierzbicka A. (1996) Semantics: Primes and Universals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198700024. Publisher’s website’s description of book Professor Wierzbicka’s faculty webpage Excepts from Chapters 1 and 2

External links

- Goddard C, Wierzbicka A (2006) Semantic Primes and Cultural Scripts in Language: Learning and Intercultural Communication. See the PDF listed.

- Goddard, Cliff. 2002. The search for the shared semantic core of all languages. In Cliff Goddard and Anna Wierzbicka (eds). Meaning and Universal Grammar - Theory and Empirical Findings. Volume I. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. pp. 5-40.

- The Natural Semantics Metalanguage HomePage