Helicobacter pylori: Difference between revisions

imported>Jignisha Patel |

imported>Jignisha Patel |

||

| Line 29: | Line 29: | ||

==Pathology== | ==Pathology== | ||

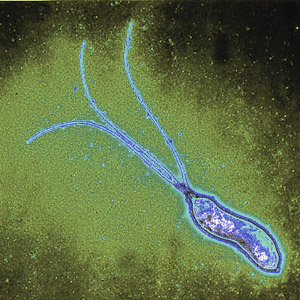

[[Image: Helicobacter Pylori Urease.png]] | |||

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common bacterial infections in humans and it is present in almost half of the world population. One of the main reasons why it is able to infect its hosts is because it produces large amounts of urease enzyme. Urease breaks urea down into carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia neutralizes the gastric acid that is present in the stomach and it is toxic to the epithelial cells. Due to the urease activity, H. pylori is able to tolerate the acidic environment; without urease it would die. Another reason why it is able to colonize is because the host immune system is unable to cross into the mucus lining. Initially in the presence of H. pylori, white blood cells, killer T- cells and infection fighting agents are sent to the site. But since they are unable to cross the mucus lining, the immune response just keeps growing and the immune cells end up dying at the location of the mounting immune response. The dead immune cells release cytotoxic agents, which is extra nutrients for the bacterial cells. This leads to gastritis and eventually ulcers. Most people will never have symptoms or problems related to the infection so it is hard to tell when someone gets the infection. But some symptoms can be loss of weight, loss of appetite, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and gnawing pain. But these symptoms may also be the result of other medical conditions so further tests would be required to confirm the presence of H. Pylori. | Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common bacterial infections in humans and it is present in almost half of the world population. One of the main reasons why it is able to infect its hosts is because it produces large amounts of urease enzyme. Urease breaks urea down into carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia neutralizes the gastric acid that is present in the stomach and it is toxic to the epithelial cells. Due to the urease activity, H. pylori is able to tolerate the acidic environment; without urease it would die. Another reason why it is able to colonize is because the host immune system is unable to cross into the mucus lining. Initially in the presence of H. pylori, white blood cells, killer T- cells and infection fighting agents are sent to the site. But since they are unable to cross the mucus lining, the immune response just keeps growing and the immune cells end up dying at the location of the mounting immune response. The dead immune cells release cytotoxic agents, which is extra nutrients for the bacterial cells. This leads to gastritis and eventually ulcers. Most people will never have symptoms or problems related to the infection so it is hard to tell when someone gets the infection. But some symptoms can be loss of weight, loss of appetite, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and gnawing pain. But these symptoms may also be the result of other medical conditions so further tests would be required to confirm the presence of H. Pylori. | ||

Revision as of 17:47, 1 April 2008

Articles that lack this notice, including many Eduzendium ones, welcome your collaboration! |

Classification

Higher order taxa

Domain: Bacteria ; Phylum: Proteobacteria; Class: Epsilon Proteobacteria; Order: Campylobacterales; Family: Helicobacteraceae [Others may be used. Use Tree of Life link to find]

Species

Helicobacter pylori

Description and significance

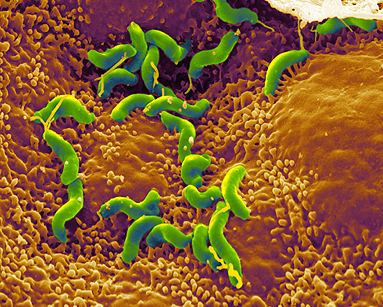

Helicobacter pylori is a spiral-shaped gram-negative bacterium that infects the stomach. It can cause damage to stomach and duodenal tissue, which causes ulcers, gastritis (inflammation of the gastric mucosa of the stomach), and in some cases cancer. Robin Warren and Barry Marshall discovered the bacterium in 1982 and they were the first to culture it successfully. They purposed that it was H. pylori that caused stomach ulcers but this was not recognized at that time because people debated over whether the stomach environment would allow bacteria to survive. To prove their point, Marshall drank a Petri dish of H. pylori and he developed gastritis. The bacteria was isolated from the lining of his stomach and this proved three out of four of Koch’s postulates (which establish the relationship between a microbe and a disease). Further investigations went on to determine the relationship between H. pylori and ulcers and numerous studies around the world confirmed this. The National Institute of Health confirmed that gastric ulcers are caused by H. Pylori in 1994.

Genome structure

Helicobacter pylori contains one circular chromosome that carries 1,667,867 base pairs. It has about 1590 coding regions. The genome has been sequenced and it is being studied and compared to find out more about its lifestyle and pathogenicity.

Cell structure and metabolism

Helicobacter pylori is a slow growing helical-shaped gram-negative bacterium with flagella. It’s a microaerophilic bacterium, meaning that it requires oxygen at lower levels compared to the oxygen level in the atmosphere. It can use hydrogenase to obtain energy. Hydrogenase produces energy by oxidizing molecular hydrogen that is produced by the bacteria present in the intestine.

Ecology

Helicobacter pylori lives in the acidic environment of the stomach and duodenum where many other microorganisms would not survive. The flagella is used to drill through the mucus gel layer of the stomach. H. Pylori has been found to live inside the mucus gel layer, above epithelial cells, and inside vacuoles in the epithelial cells. Adhesins allow it to adhere to epithelial cells by attaching to membrane-bound lipids and carbohydrates. Other animals such as dogs, cats, and ferrets have also been infected by H. pylori. In the humans, infection leads to gastritis which if left untreated leads to the formation of ulcers. In the long run this can possibly cause gastric cancer.

Pathology

Helicobacter pylori is one of the most common bacterial infections in humans and it is present in almost half of the world population. One of the main reasons why it is able to infect its hosts is because it produces large amounts of urease enzyme. Urease breaks urea down into carbon dioxide and ammonia. The ammonia neutralizes the gastric acid that is present in the stomach and it is toxic to the epithelial cells. Due to the urease activity, H. pylori is able to tolerate the acidic environment; without urease it would die. Another reason why it is able to colonize is because the host immune system is unable to cross into the mucus lining. Initially in the presence of H. pylori, white blood cells, killer T- cells and infection fighting agents are sent to the site. But since they are unable to cross the mucus lining, the immune response just keeps growing and the immune cells end up dying at the location of the mounting immune response. The dead immune cells release cytotoxic agents, which is extra nutrients for the bacterial cells. This leads to gastritis and eventually ulcers. Most people will never have symptoms or problems related to the infection so it is hard to tell when someone gets the infection. But some symptoms can be loss of weight, loss of appetite, bloating, nausea, vomiting, and gnawing pain. But these symptoms may also be the result of other medical conditions so further tests would be required to confirm the presence of H. Pylori.

Current Research

Enter summaries of the most recent research here--at least three required